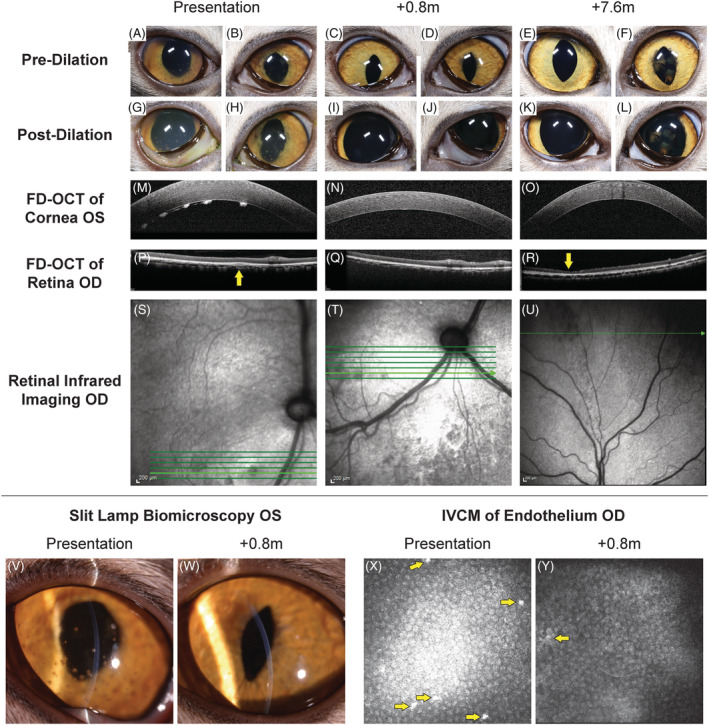

FIGURE 2.

Sequential multimodal imaging of the cranial and caudal segments from Case 4. At presentation (A, B) predilatation and (G, H) postdilatation cranial segment photographs showing mild diffuse corneal edema, pigmented keratic precipitates, rubeosis iridis, obscured detail of the iris because of aqueous flare, and incomplete dilatation OU; dyscoria with incomplete pupillary dilatation because of caudal synechia OS (H) was also observed. Keratic precipitates were also visualized OS with slit lamp biomicroscopy (V), corneal FD‐OCT (M), and IVCM of the endothelium (X, arrows); increased corneal thickness was also observed with FD‐OCT (X). Imaging of the retina and choroid with FD‐OCT revealed cellular infiltrate in the choroid (P, arrow) that was visible as a hyporeflective lesion with infrared photography (S). At 0.8 months after initiation of GS‐441524 treatment, pre‐ (C,D) and postdilatation (I,J) cranial segment photographs demonstrated clear corneas and cranial chambers OU, isocoria, decreased rubeosis iridis, and complete pupillary dilatation OS. A marked decrease in pigmented keratic precipitates was noted with slit lamp biomicroscopy (W), corneal FD‐OCT (N), and IVCM of the endothelium (Y, arrow). Normal retinal and choroidal morphology is observed with FD‐OCT (Q) although the hyporeflective lesions remain with infrared imaging (T). At 7.6 months, pre‐ (E,F) and postdilatation (K, L) cranial segment photographs demonstrated clear corneas and cranial chambers OU, isocoria, normal iris morphology, and postinflammatory pigment on the cranial lens capsule OS. Keratic precipitates are absent with corneal FD‐OCT (O). With FD‐OCT and infrared imaging, thinning of the dorsal peripheral retina was present (R, arrow) with loss of the normal layering but no cellular infiltrate or retinal separation (U)