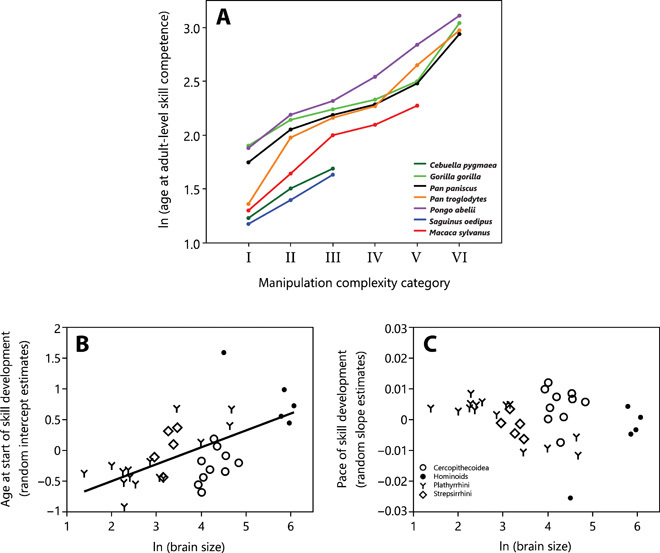

Fig. 5. Immatures in large-brained species with a more complex manipulation repertoire need more time to develop their adult-level skill competence because they are older when they reach the first, simplest skill level.

(A) Example of seven species illustrating the different starting points but the same pace of the development of food manipulation. (B) Larger-brained primate species start at an older age to manipulate food items, as shown by the relationship between brain size (log-transformed) and the estimated age at which infants of a given species first engage in unimanual grasping [approximated by random intercept estimates of the function log (age) ~ level with species as a random factor]. (C) Larger-brained primates do not transition more slowly to higher levels of manipulation complexity, as shown by the relationship between brain size (log-transformed) and the pace at which species move through the series of cumulative motor skills [approximated by the random slope estimates of the function level ~ log (age) with species as a random factor]. The notable hominoid outlier is the pileated gibbon (H. pileatus). The silvery gibbon (H. moloch) was excluded because it did not follow the order of emergence of the food manipulation categories during ontogeny of all the other species.