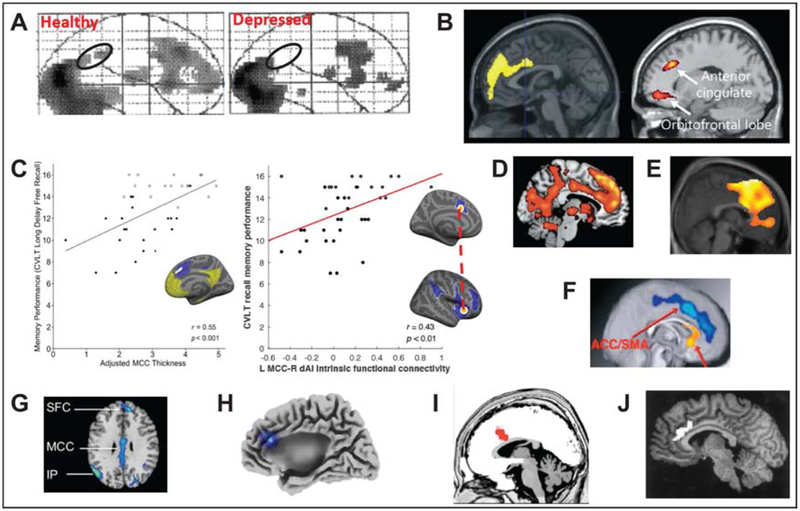

Figure 3.

Implications of the aMCC role in tenacity. Compared to healthy controls, patients with depression show reduced regional cerebral blood flow in the aMCC (black circle) during an effortful task (A)(Elliott et al., 1997); apathy scores correlate with altered glucose metabolism in aMCC in early dementia including Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia (left, (Schroeter et al., 2011) and Parkinson’s disease (right, labeled as ‘ACC’ by the authors (Huang et al., 2013) (B); aMCC cortical thickness (left, aMCC indicated with white)(Sun et al., 2016) and intrinsic connectivity to anterior insula (right (Zhang et al., 2019)) both predict successful memory performance in superagers and typical older adults (C); aMCC signal increases during effortful memory retrieval in older adults (D)(Dhanjal and Wise, 2014); high exercise intensity is linked to metabolic changes in aMCC (E)(Kemppainen et al., 2005); gray matter volume in frontal regions including the aMCC was increased (blue) for aerobic exercisers relative to nonaerobic controls (F)(Colcombe et al., 2006); obese adolescents show aMCC weaker activation in response to foods compared to lean adolescents (G) (Carnell et al., 2017); transcranial pink noise stimulation of aMCC decreases self-reported desire to eat in women with obesity (H)(Leong et al., 2018); aMCC activity during task increases in individuals who follow the task instructions closely (I)(Mulert et al., 2005); aMCC regional blood flow is associated with faster reaction times in a somatosensory reaction time task (J)(Naito et al., 2000).