Abstract

Current strategies to treat tuberculosis (TB) and co-morbidities involve multidrug combination therapies. Rifamycin antibiotics are a key component of TB therapy and a common source of drug–drug interactions (DDIs) due to induction of drug metabolizing enzymes (DMEs). Management of rifamycin DDIs are complex, particularly in patients with co-morbidities, and differences in DDI potential between rifamycin antibiotics are not well established. DME profiles induced in response to tuberculosis antibiotics (rifampin, rifabutin and rifapentine) were compared in primary human hepatocytes. We identified rifamycin induced DMEs, cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C8/3A4/3A5, SULT2A, and UGT1A4/1A5 and predicted lower DDIs of rifapentine with 58 clinical drugs used to treat co-morbidities in TB patients. Transcriptional networks and upstream regulator analyses showed FOXA3, HNF4α, NR1I2, NR1I3, NR3C1 and RXRα as key transcriptional regulators of rifamycin induced DMEs. Our study findings are an important resource to design effective medication regimens to treat common co-conditions in TB patients.

Subject terms: Pharmacology, Antimicrobials

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide1 and antibiotic therapy is a major infection-controlling measure in persons with either latent or active TB infection2. Human immunodeificency virus (HIV)-TB co-infected persons are susceptible to bacterial, viral, and fungal opportunistic infections (OIs) and moreover, cancer co-exist in more than four percent of active TB patients, which add to morbidity and mortality3–8. Concurrent treatment of TB, HIV, OIs and cancer often necessitates polypharmacy, and requires management of drug-drug interactions (DDI) to prevent detrimental treatment outcomes.

Drug-susceptible TB is currently treated with 6 months of daily rifampin therapy, which is combined with other antibiotics such as isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol9. Additionally, many of the current treatment options for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) and prophylactic regimens for TB involve the use of rifampin or rifapentine9–11. Rifamycin antbiotics are known to be a common cause of DDIs with co-administered medications via induction of drug metabolizing enzymes (DMEs). Clinical DDI data guide the management of rifamycin DDIs during polypharmacy, but comprehensive clinical DDI data are not available across all rifamycin antibiotics to manage common medication therapies to treat co-morbidities such as HIV and OIs in TB patients10,11.

The primary human hepatocyte (PHH) model is a gold standard to unravel potential DDIs through expression profiling of genes encoding enzymes and transporters that alter drug metabolism12. In this process, the application of highly sensitive next generation sequencing (NGS) technology determines changes in extremely low DME transcript copy numbers expressed in PHHs to understand their role in metabolism and disposition of drugs interacting with rifamycins. Then, transcriptomic data obtained in NGS is used in a downstream systems pharmacology approach to identify novel targets, which allows better understanding of potential DDIs and prediction of effectiveness of a drug regimen during co-prescription of medications13–16.

Several potential DDIs associated with rifamycins remain unaddressed. First, studies utilizing NGS to profile rifamycin responsive genes (RGs) to predict clinical DDI outcomes have not been conducted. Second, data available on rifampin associated DDIs are complex due to in-vitro data generation in alternative hepatic cell line models and seldom in PHHs17. While translatability of these alternative hepatocyte models to PHHs is unclear, complexity is further increased when PHHs were derived from volunteers who were exposed to alcohol, tobacco, and medications which may have a direct influence on DME profiles and thereby potential DDI inferences18,19. Finally, no comparative study has been performed on transcriptional responses of rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine in PHHs to examine and compare independent and integrated gene signatures, underlying pathways, networks, and metabolic programs, which are key molecular events underlying rifamycin mediated DME expression and associated DDIs.

In response to these key knowledge gaps, we applied NGS in tandem with systems pharmacology tools to determine DME expression profiles in metabolically active PHHs derived from three healthy (drug/tobacco/alcohol free) volunteers in response to rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine. We have identified integrated transcriptional signatures of rifamycin drugs and pathways that regulate drug metabolism, networks of genes, and transcriptional programs regulating drug metabolism. This information was used to predict outcomes of potential DDIs with rifamycins and drugs used to treat HIV, cancer, and other common disease states in TB patients.

Results

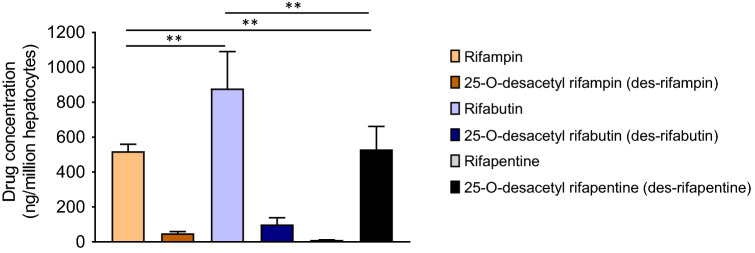

Rapid metabolism of rifapentine in PHHs among rifamycins

PHH associated rifamycin intracellular concentrations (geometric mean) at 72 h post equimolar treatment were: rifabutin (879.1 ± 211.7, mean (ng/million cells) ± standard deviation (SD)), rifampin (519.5 ± 39.4) and rifapentine (10.57 ± 1.1) (Fig. 1). Metabolite to parent (Cm/Cp) ratios of rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine to 25-O-desacetyl rifampin (des-rifampin), 25-O-desacetyl rifabutin (des-rifabutin), and 25-O-desacetyl rifapentine (des-rifapentine) metabolites were 0.09, 0.10 and 48.93, respectively (Fig. 1). Results were consistent among three lots of PHHs derived from three independent healthy donors who were free of drug, tobacco, alcohol, and medicine usage (demographic details are listed in Table S1). These results show that in PHHs, rifampin and rifabutin have higher intracellular concentrations than rifapentine due to its rapid metabolism to antimicrobially active des-rifapentine.

Figure 1.

Bioavailability of parent rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine drugs and their des-metabolites in primary human hepatocytes (PHHs). PHHs derived from healthy donors were independently treated with rifamycin antibiotics (10 µM) for 72 h. Intracellular concentration of parent to metabolites (Cp/Cm) were quantified using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analysis and drug concentration per million PHHs are shown.

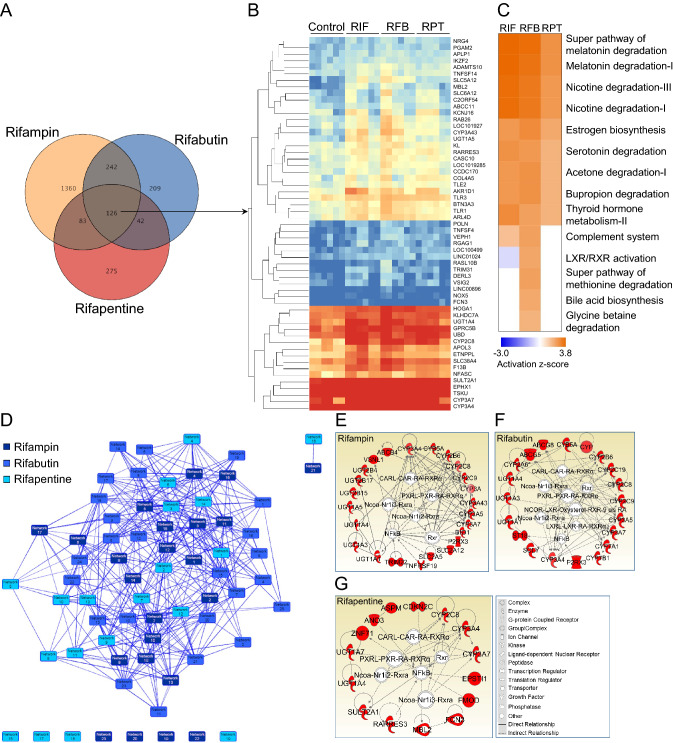

Transcriptomic analysis identified integrated gene signatures of rifamycins in PHHs

Transcriptomic analysis showed that a number of rifapmin, rifabutin, and rifapentine associated transcripts were significantly (p < 0.05) altered (> 1.5 fold change [FC]) 619 (1.53%), 1811 (4.47%), and 526 transcripts (1.3%), respectively in PHHs as compared to vehicle (methanol, 0.0025%) treated controls (Figure S1A, S1B and S1C). Since rifabutin and rifapentine are structural analogues of rifampin, which was originally modified from rifamycin B, we have predicted expression of a unique set of integrated transcripts with similar expression patterns in all rifamycins or in pairs (rifampin and rifabutin, rifabutin and rifapentine, and rifampin and rifapentine). We performed a venn diagram analysis and identified 126 transcripts (0.31%) that were significantly regulated by all rifamycin drugs and constitute an integrated gene signature (Fig. 2A and B). A total of 368 transcripts in rifampin (59.45%) and rifabutin (20.32%), 209 in rifabutin (11.54%) and rifapentine (39.73%), and 168 in rifampin (27.14%) and rifapentine (31.93%) were altered at the transcriptional level in their combinatorial responses in PHHs (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, a total of 20.3% of total rifampin, 6.9% of rifabutin, and 23.9% of rifapentine regulated differentially expressed genes were contributing to the integrated rifamycin gene signature (Fig. 2B). These results showed that < 4.5% of whole transcriptomic changes overlap among the rifamycins and that the responsive transcriptomes contain a large number of transcripts that are characteristically regulated by each rifamycin in PHHs.

Figure 2.

Integrated gene signature of rifamycin antibiotics and pathways induced in PHHs in response to 10 µM of rifampin (RIF), rifabutin (RFB) and rifapentine (RPT) treatment. (A) Rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine responsive transcripts either uniquely, combinedly, or uniformly regulated among rifamycins in PHHs are shown. (B) Heat map shows a total of 126 transcripts that are uniformly regulated among rifamycins, and transcripts were organized based on their level of mRNA expression. (C) Biological and metabolic pathways significantly (< 0.01 p value, 0.1 ratio) regulated based on a list of up regulated transcripts in response to rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine in PHHs as compared to controls are shown. (D) Interactive transcriptional networks of rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine responsive genes regulated in PHHs following drug treatments. (E) Drug metabolism networks (DMNs) of drug metabolizing enzyme (DME) transcripts specifically induced by rifampin, (F) rifabutin, and (G) rifapentine built using ingenuity pathway analysis software are shown. Red color indicates the up regulation of a transcript. Transcription factors regulating the expression of drug metabolism genes are shown in the center of the network.

DME profiles in rifamycin responsive PHHs predict lower drug interaction potential of rifapentine

Rifamycin responsive PHH transcriptomes consisted of distinct sets of DMEs. A total of 19 cytochrome P450 genes (CYPs) were induced by rifamycins, and CYP2A1 was the only down regulated CYP transcript post rifabutin treatment (Table 1). In this analysis, four CYPs, CYP2C8, 3A4, 3A7, and 3A43, were integral to all rifamycin responses. CYP3A4, a key DME known to regulate the metabolism of a large number of drugs, followed a FC pattern, rifapentine (6.8) < rifampin (16.7) < rifabutin (25.5) (Table 1). Among UDP-glucose-glycoprotein glucosyltransferases (UGTs), 1A4 and 1A5 were induced by rifamycins, UGT1A1 and 1A3 by rifampin and rifabutin, while others were unique to individual rifampin and rifapentine treatment (Table 1). Among non-CYP classes of genes that regulate drug metabolism, rifamycin induced ATP binding cassette protein (ABCC) 11, apolipoprotein (APOL) 3; rifampin and rifabutin induced ATP binding cassette subfamily B, member 1 (ABCB1), ABCB4, ABCC6P1, ABCC7, and all others were unique to rifamycins (Table S2). Among 56 solute carrier family proteins (SLCs), expression of SLC6A12 and 38A4 were induced, and 42A3 was down regulated by all rifamycins (Table S2). These data showed that rifamycins induced a large number of metabolism-associated genes, but only 6.28% (12 out of 191) of transcripts were integral to all rifamycins, while others were unique to each of the rifamycin drug responses. Expression profiles of CYP3A4 and other DME transcripts described above showed that rifapentine may have lower DDI potential among rifamycins. Table 1 summarizes the FC of associated DME genes in response to individual rifamycin drug treatment.

Table 1.

Drug metabolizing enzymes (DMEs) significantly (> 1.5 fold change and < 0.05p value) regulated in response to rifampin (RIF), rifabutin (RFB) and rifapentine (RPT) at 10 μM in primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) as compared to vehicle (methanol, 0.0025%) treated controls. NCBI gene IDs are shown under the column ID#.

| Gene | RIF | RFB | RPT | ID# | Gene | RIF | RFB | RPT | ID# | Gene | RIF | RFB | RPT | ID# | Gene | RIF | RFB | RPT | ID# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug metabolizing enzymes (DMEs) | |||||||||||||||||||

| I. Oxidative Phase I enzymes | B. Monoamine oxidases (MAOs) | H. Glutathione peroxidases (GPXs) | N. Alkaline phosphatases (ALPs) | ||||||||||||||||

| A. Cytochrome P 450 enzymes (CYPs) | MAOB | 1.7 | 4,129 | GPX2 | 2.1 | 2,877 | ALPI | 15.6 | 248 | ||||||||||

| CYP2A1 | − 1.7 | 1543 | C. Aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs) | I. Carboxypeptidases | ALPL | 2.4 | 249 | ||||||||||||

| CYP2A6 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 1548 | ALDH1A2 | 2.0 | 8,854 | SCPEP1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 59,342 | O. N-acetyltransferases (NATs) | ||||||||

| CYP2A7 | 2.6 | 5.0 | 1549 | ALDH1L1 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 10,840 | CPA4 | − 3.2 | 51,200 | NAA15 | − 1.5 | 80,155 | ||||||

| CYP2A13 | 4.2 | 5.9 | 1553 | ALDH3A1 | 1.7 | 218 | CPO | 1.7 | 130,749 | SAT2 | 1.5 | 112,483 | |||||||

| CYP2B6 | 6.1 | 3.7 | 1555 | ALDH5A1 | 1.5 | 7,915 | CPVL | 1.6 | 1.9 | 54,504 | P. Amino acid conjugating enzymes | ||||||||

| CYP2B7P | 3.6 | 3.5 | 5.1 | 1556 | ALDH6A1 | 1.8 | 4,329 | J. Endopeptidases | ACSL4 | − 2.2 | 2,182 | ||||||||

| CYP2C8 | 13.5 | 18.1 | 1558 | ALDH8A1 | 2.4 | 64,577 | PHEX | 1.5 | 5,251 | ACSL6 | 1.8 | 23,305 | |||||||

| CYP2C9 | 2.7 | 4.3 | 1559 | II. Reductive phase I DMEs | IV. Conjugative phase II DMEs | ACSM1 | 3.1 | 116,285 | |||||||||||

| CYP2C19 | 1.8 | 1557 | D. Aldo–keto reductases (AKRs) | K. UDP glucuronosyl transferases (UGTs) | ACSM2A | 1.8 | 3.1 | 123,876 | |||||||||||

| CYP2S1 | 2.0 | 29,785 | AKR1B1 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 231 | UGT1A1 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 54,658 | ACSM2B | 2.8 | 348,158 | ||||||

| CYP2W1 | 2.1 | 54,905 | AKR1D1 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 6,718 | UGT1A3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 54,659 | ACSM3 | 2.4 | 6,296 | |||||

| CYP3A4 | 16.7 | 25.5 | 6.8 | 1576 | AKR1A1 | 1.5 | 10,327 | UGT1A4 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 54,657 | ACSS1 | 2.1 | 84,532 | ||||

| CYP3A5 | 2.6 | 3.7 | 1577 | AKR1B10 | − 3.7 | 57,016 | UGT1A5 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 2.1 | 54,579 | GLYAT | 3.1 | 10,249 | |||||

| CYP3A7 | 6.2 | 7.3 | 3.3 | 1551 | AKR1B15 | − 2.5 | − 3.0 | 441,282 | UGT1A8 | 1.8 | 54,576 | LPCAT4 | − 1.6 | 254,531 | |||||

| CYP3A43 | 5.8 | 9.1 | 3.1 | 64,816 | AKR1C6P | 3.1 | 389,932 | UGT1A9 | 1.6 | 54,600 | LRAT | 1.9 | 9,227 | ||||||

| CYP4V2 | 1.7 | 285,440 | AKR7A2P1 | 1.7 | 246,182 | UGT1A10 | 1.5 | 54,575 | Q. Methyl Transferases (MTs) | ||||||||||

| CYP7A1 | 9.4 | 1581 | E. Quinone reductases | UGT2B4 | 1.6 | 7,363 | AS3MT | 1.5 | 57,412 | ||||||||||

| CYP7B1 | 1.6 | 9,420 | NQO1 | − 2.5 | 1728 | UGT2B15 | 2.2 | 7,366 | BHMT | 3.4 | 1.6 | 635 | |||||||

| CYP11A1 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1583 | III. Hydrolytic Phase I DMEs | UGT2B17 | 2.3 | 7,367 | DOT1L | − 1.5 | 84,444 | |||||||||

| CYP21A1P | 1.5 | 1,590 | F. Epoxide hydrolases (EPHXs) | L. Sulfotransferases (SULTs) | |||||||||||||||

| Other Cytochrome transcripts | EPHX1 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 2052 | SULT2A1 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 6,822 | HNMT | 1.6 | 3,176 | ||||||

| CYBA | 2.2 | 1535 | G. Aminopeptidases | SULT4A1 | 2.0 | 25,830 | METTL7A | 1.5 | 25,840 | ||||||||||

| CYB5A | 2.2 | 1.6 | 1528 | ENPEP | 1.9 | 2028 | M. Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) | METTL7B | − 1.5 | 196,410 | |||||||||

| CYB5D2 | 1.5 | 124,936 | ERAP1 | 1.7 | 51,752 | GSTM2 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2,946 | NNMT | − 2.3 | 4,837 | |||||||

| CYB5RL | 1.7 | 606,495 | ASPRV1 | 1.8 | 151,516 | GSTT2B | 1.7 | 653,689 | TRMT10A | − 1.6 | 93,587 | ||||||||

| CYBRD1 | 1.9 | 79,901 | MASP1 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 5,648 | |||||||||||||

Lower interaction potential of rifapentine with therapeutics used to treat HIV, cancer and other co-morbidities in TB patients

One of the major objectives of our study was to identify potential interactions of rifamycins with drugs used to treat common comorbidities in TB patients. In this process, DME expression profiles from the list of rifamycin-RGs were an important resource to predict clinical DDIs. The most important qualitative features of NGS are (i) sequence accuracy and (ii) gene features, including, coding (exon), non-coding (intron), intergenic, and untranslated regions. RNA profiles of our study samples showed near to 100% perfect index reads and maintained similar exon and intron sequences among replicates of rifampin, rifabutin, rifapentine treated and control (methanol and untreated) samples (Figures S2 and S3), which confirmed their quality and improved confidence in our data. With the disease and function annotation analysis tool in ingenuity pathway analysis software, we predicted the interaction of rifamyins with 58 FDA-approved drugs. Among these drugs, 17 were used to treat HIV, 10 to treat cancer, one to treat malaria and two to treat fungal infections (Table 2). Among anti-HIV drugs, protease inhibitors, including, atazanavir, darunavir, fosamprenavir, lopinavir, saquinavir, tipranavir, and the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, rilpivirine, and pharmacokinetic enhancers, cobicistat and ritonavir, are all readily metabolized by hepatic CYP3A4 (Table 2). Based on CYP3A4 regulation, we have identified a comparative DDI pattern of rifapentine < rifampin < rifabutin (Table 2). Rifampin and rifabutin induced UGT1A1, which is involved in raltegravir and abacavir metabolism (Table 2) with a comparative DDI pattern, rifapentine < rifampin < rifabutin. Multiple DMEs are involved in the major metabolism of many antiretroviral drugs, including dolutegravir, elvitegravir, efavirenz, etravirine, and nevirapine (Table 2), based on deducibility, rifapentine may have lower drug interaction potential as compared to rifampin and rifabutin when used in combination with these antiretrovirals. Disease and function annotation analysis predicted interaction of rifamycins with other drugs used to treat multiple diseases in TB patients (Table 3). These data summarize the DDI potential of rifamycins and indicate a lower interaction potential of rifapentine among rifamycins.

Table 2.

Predicted drug-drug interaction (DDI) potential of rifamycin antibiotics with therapeutics used to treat HIV, fungal, malarial parasitic infections and cancer in tuberculosis patients.

| Interacting drugs | Drug metabolizing enzymes induced during treatment | DDI pattern | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampin (RIF) | Rifabutin (RFB) | Rifapentine (RPT) | ||

| Antiretroviral Drugs (ARVs) | ||||

| ARV Category I: Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs) | ||||

| Dolutegravir | CYP3A4, UGT1A1 | CYP3A4, UGT1A1 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Bictegravir | CYP3A4, UGT1A1 | CYP3A4, UGT1A1 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Elvitegravir | CYP3A4, UGT1A1, UGT1A3 | CYP3A4, UGT1A1, UGT1A3 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Raltegravir | UGT1A1 | UGT1A1 | RPT < RIF < RFB | |

| ARV Category II: Non-nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs) | ||||

| Efavirenz | CYP2A6, 2B6 | CYP2A6, 2B6, 2C19 | RPT < RIF < RFB | |

| Etravirine | CYP3A4, 2C9 | CYP3A4, 2C9, 2C19 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Nevirapine | CYP3A4, 2B6 | CYP3A4, 2B6 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF/RFB |

| Rilpivirine | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| ARV Category III: Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs) | ||||

| Abacavir | UGT1A1 | UGT1A1 | RPT < RIF < RFB | |

| ARV Category IV: Protease Inhibitors (PIs) | ||||

| Atazanavir | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Darunavir | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Fosamprinavir | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Lopinavir | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Saquinavir | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Tipranavir | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| ARV Category IV: Entry Inhibitors (EIs) | ||||

| Maraviroc | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| ARV Category V: Pharmacokinetic enhancers (PK boosters) | ||||

| Cobicistat | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Ritonavir | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Antifungals | ||||

| Terbinafine | CYP2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2B6, 2C19, 2C8, 2C9, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2C8, 3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Voriconazole | CYP2C9,CYP3A5 | CYP2C9,CYP2C19,CYP3A5 | - | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Antimalarials | ||||

| Quinine | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Anticancer Drugs | ||||

| Beta-estradiol | CYP3A4, 3A5, 3A7 | CYP3A4, 3A5, 3A7 | CYP3A4, 3A7 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Cyclophosphamide | CYP2A6, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 3A4 | CYP2A6, 2B6, 2C19, 2C8, 2C9, 3A4 | CYP2C8, 3A4 | RPT < RIF & RFB |

| Docetaxel | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Etoposide | CYP2C9, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2C9, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Ifosfamide | CYP2A6, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 3A4 | CYP2A6, 2B6, 2C19, 2C8, 2C9, 3A4 | CYP2C8, 3A4 | RPT < RIF & RFB |

| Omeprazole | CYP2A6, 2C9, 3A4 | CYP2A6, 2C19, 2C9, 3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Paclitaxel | CYP2B6, 2C8, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2B6, 2C8, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2C8, 3A4 | RPT < RIF & RFB |

| Tamoxifen | CYB5A, CYP2B6, 2C9, 3A4, 3A5; UGT2B15 | CYP5A, 2B6, 2C19, 2C9, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF & RFB |

| Thalidomide | CYP2C9, 3A5 | CYP3A5 | RPT < RIF < RFB | |

| Tretinoin | CYP2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 3A4, 3A5, 3A7 | CYP2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 3A4, 3A5, 3A7, RDH16, ALDH8A1 | CYP2C8, 2S1, 3A4,3A7 | ND |

Abbreviations: CYP, cytochrome P450; UGT, UDP glucuronosyl transferase; RDH16, Retinol dehydrogenase 16 and ALDH8A1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 8 family member A1 and ND, not determined.

Table 3.

Predicted Drug-Drug Interactions (DDIs) of rifamycins with therapeutics used to treat various illnesses in TB patients.

| Interacting drugs | Drug metabolizing enzymes induced during treatment | Predicted DDI pattern | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampin (RIF) | Rifabutin (RFB) | Rifapentine (RPT) | ||

| Anti-inflammatory drugs | ||||

| Indomethacin | - | CYP2C19, CYP2C9 | - | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Colchicine | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Anti-diabetic drugs | ||||

| Tolbutamide | CYP2C8, 2C9, 3A5 | CYP2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 3A5 | CYP2C8 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | ||||

| Sirolimus | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | ||||

| Amiodarone | CYP2C8, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2C8, 2C19, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2C8, 3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Lidocaine | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Antihypertensive drugs | ||||

| Verapamil | CYP2C8, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2C8, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2C8, 3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Antidepressant drugs | ||||

| Bupropion | CYP2B6, 3A4 | CYP2B6, 3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Imipramine | CYP2B6, 3A4, UGT1A4 | CYP2B6, 2C19, 3A4, UGT1A4 | CYP3A4, UGT1A4 | RPT < RIF & RFB |

| Morphine | CYP2C8, 3A4 | CYP2C8, 3A4 | CYP2C8, 3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Anticonvulsant drugs | ||||

| Carbamazepine | CYP2C8, 3A4, 3A5, 3A7 | CYP2C8, 3A4, 3A5, 3A7 | CYP2C8, 3A4, 3A7 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Antipsychotic drugs | ||||

| Haloperidol | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Antisedative drugs | ||||

| Midazolam | CYP2B6, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2B6, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF & RFB |

| Triazolam | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Alprazolam | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Diazepam | CYP2B6, 2C9, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2B6, 2C19, 2C9, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF & RFB |

| Vasodilators | ||||

| Sildenafil | CYP2C9, 3A4 | CYP2C9,CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Analgesics | ||||

| Methadone | CYP2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 3A4 | CYP2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 3A4 | CYP2C8, 3A4 | RPT < RIF & RFB |

| Ibuprofen | CYP2C8, 2C9 | CYP2C8, 2C9, 2C19 | CYP2C8 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Sedatives | ||||

| Midazolam | CYP2B6, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2B6, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF/RFB |

| Triazolam | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Alprazolam | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Diazepam | CYP2B6, 2C9, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP2B6, 2C19, 2C9, 3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF & RFB |

| Orexogenic drugs | ||||

| Dronabinol | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Adrenocortical insufficiency treating drugs | ||||

| Hydrocortisone | CYP3A4, 3A5, FOXA1 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | ||||

| Fluvastatin | CYP2C8, 2C9, 3A4 | CYP2C8, 2C9, 3A4 | CYP2C8, 3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Simvastatin | CYP2C9, 3A4 | CYP2C9, 3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Pravastatin | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Hormonal drugs | ||||

| Testosterone | CYP3A4, 3A5 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) treated drugs | ||||

| Escitalopram | CYP3A4 | CYP2C19, 3A4 | CYP3A4 | RPT < RIF < RFB |

| Smoking cessation aiding drugs | ||||

| Nicotine | CYP2A6, 2B6 | CYP2A6, 2B6 | RPT < RIF & RFB | |

CYP, cytochrome P450 and UGT, UDP glucuronosyl transferase.

Rifamycins are strongest but selective stimulants of drug metabolism pathways in PHHs

A total of 327, 441, and 297 pathways were induced in response to rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine treatment in PHHs respectively. Of these, activated biological pathways, 9 (2.75%), 13 (2.94%), and 7 (2.35%) were found to be significant at p = 0.01, 0.1 ratio and 2.0 Z score. In this, seven pathways were stimulated by all rifamycins (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, several of the activated drug metabolizing pathways involved CYP2C8, 3A4, 3A7, UGT1A4, 1A5, and sulfotransferase family 2A member 1 (SULT2A1) DMEs as key modulators (Table S3 and S4), which are also part of the integrated rifamycin transcriptional signature (Fig. 2B and Table S3). While rifampin-RGs independently regulated the serotonin degradation pathway, rifabutin-RGs stimulated several metabolic pathways, such as degradation of glycine, betaine, and methionine and bile acids biosynthesis as shown in Table S4. Even in down regulated pathways, rifabutin inhibited 9 cell signaling and 2 metabolic pathways, including geranyl diphosphate and cholesterol biosynthesis (Figure S4 and Table S5). Rifampin and rifapentine did not significantly inhibit any pathways and showed their distinction from rifabutin regulatory transcriptional pathways. These results showed that rifamycins strongly stimulate drug metabolic pathways in PHHs involving CYP2C8, 3A4, 3A7, UGT1A4, 1A5, and SULT2A1 as key regulators.

Interactive transcriptional drug metabolism networks predict the role of NCOA, NF-KB, NR1I2, NR1I3 and RXRα transcription factors in regulation of DMEs in rifamycin responsive PHHs

A tightly regulated gene network is dedicated to perform a specific function in drug responsive cellular transcriptomes. From a network analysis of rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine regulatory DME profiles, we found 23 rifampin, 25 rifabutin, and 19 rifapentine gene networks are operated in PHHs following their independent treatments (Fig. 2D). In rifamycin responsive gene networks, 1 through 18 rifampin, all of rifabutin, and 1 through 14 rifapentine regulated networks were dedicated to cell signaling and drug metabolism functions. Among transcriptomic networks, rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine responsive 2nd, 6th, and 10th networks were specifically associated with drug metabolism.

These drug metabolism networks (DMNs) involve ≤ 24 DMEs; CYP2C8, 3A4, and 3A7; UGT1A4 and 1A5 were integral to these networks (Fig. 2E–G). No common transcripts were found in either rifabutin and rifapentine or rifampin and rifapentine combinedly regulated networks. However, both rifampin and rifabutin regulated DMEs, including, CYP2A6, 2B6, 2C9, 3A5, UGT1A1, 1A5, and P2RX3 in DMNs (Fig. 2E and F). These data demonstrate the distinction of rifapentine from rifampin and rifabutin functional responses in PHHs and also suggest rifapentine may have lower DDI potential with drugs metabolized by these transcripts. Along with more than one rifamycin antibiotic regulated genes, drug metabolizing networks had a set of genes that were unique to each of the rifamycin drugs in their DMNs (Fig. 2E–G). DMNs have provided valuable data on rifamycin regulated NCOA- NR1i2/NR1i3-RXRα; RXR; NF-KB; NR1I2L-NR1I2-RA-RXRα transcription factor (TF) axes controlling the expression of downstream DME targets involved in drug metabolism (Fig. 2E–G). Along with above results, rifampin and rifabutin together controlled DMN through downstream NR1I3L-NR1I3-RA-RXRα TF axis, and rifabutin regulated DMN was specifically controlled by NCOR-LXR-Oxysterol-RXR-9-Cis RA TF axis (Fig. 2E, F). These data conclude that more than 14 rifamycin responsive transcriptional networks are operated by key TFs, NR1I2, NR1I3 (NR1I3), NCOA, RXRα and NF-KB, which control DME expression in DMNs of rifamycin responsive PHH transcriptomes.

Upstream regulator analysis of rifamycin responsive genes predict FOXA3, HNF4α, NR1I2, NR1I3, NR3C1, and RXRα as key regulators of metabolic programs in PHHs

Further validation of TF axes involving NCOA, NF-KB, NR1I2, NR1I3 and RXRα was performed using the upstream regulator analysis (URA) tool in IPA. In this analysis, we allocated rifamycin-RGs containing DMEs and drug transporters as target genes of TFs, which may control their mRNA expression. URA predicted FOXA3, HNF4α, NR1I2, NR1I3, NR3C1, and RXRα TFs are potentially involved (< 0.05 p and > 2.0 z score), and each regulated more than 10 DMEs and drug transporter targets from the list of rifamycin-RGs (Table 4 and Table S6). Based on z (> 1.0) and p value (< 0.01) based measures, all rifamycin drugs significantly activated rifamycin-RGs controlled by NR1I3, whereas both rifampin and rifabutin-RGs were targets of HNF4α, NR1I2, NR3C1, and RXRα and showed higher specificity to control rifabutin-RG targets (Table 4 and Table S6). NR1I3 heterodimerizes with RXRα and regulates a distinct set of metabolic genes in hepatocytes. In our dataset, we found 20 rifamycin-RGs as NR1I3 targets and 1 (5%) was induced by rifampin, 5 (25%) by rifabutin, 8 (40%) by both rifampin and rifabutin, 1 (5%) by both rifabutin and rifapentine, and 5 (25%) by all rifamycins (Table 4 and Table S6). In the liver, HNF4α and NR1I2 are specifically expressed to higher levels. In our dataset, HNF4α was predicted to regulate 145 rifamycin-RG targets, and in this analysis 10.3% rifampin (15 genes), 56.5% rifabutin (82 genes), and 9.6% rifapentine (14 genes) were specific to individual rifamycins, and 13.1% to rifampin and rifabutin (19 genes), 2.7% to rifabutin and rifapentine (4 genes), and 7.5% to all rifamycins (11 genes) (Table S6). Notably, the NR1I2 receptor bound to rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine and induce expression of its target genes. A total of 22 rifamycin-RGs were identified as NR1I2 targets in our dataset, including 10 regulated by rifabutin (45.4%), 7 by both rifampin & rifabutin (31.8%), 1 by both rifabutin and rifapentine (4.5%), and 5 by all rifamycins (22.7%) (Table S6). NR1I2 heterodimerizes with RXRα to regulate expression of a unique set of metabolic genes. In a total of 34 RXRα’s rifamycin-RG targets, 5 were regulated by rifampin (14.7%), 12 by rifabutin (35.2%), 4 by rifapentine (11.7%), 10 by both rifampin and rifabutin (29.4%), and 3 (8.8%) by all rifamycins (Table S6). Induction of NR3C1 TF was predicted based on it’s association with 55 targets in URA. In this analysis, 8 genes (14.5%) were regulated by rifampin, 24 (43.6%) by rifabutin, 7 (12.7%) by rifapentine, 7 (12.7%) by both rifampin and rifabutin, 7 (12.7%) by all rifamycins, and 1 (1.8%) by rifampin & rifapentine (Table S6). CYP2C8, 3A4, and 3A8 were key DMEs that metabolized a wider array of drugs that are controlled by multiple TFs, including, FOXA3, HNF4α, NR1I2, NR1I3, and NR3C1 (Table S6). In summary, URA results showed that HNF4α, NR1I2, NR1I3, FOXA3, NR3C1, and RXRα are key TFs controlling expression of key metabolic genes, including CYP3A4.

Table 4.

Transcription factors (TFs) predicted to control the expression of target gens induced during rifampin (RIF), rifabutin (RFB) and rifapentine (RPT) treatment in hepatocytes that further regulate drug metabolism networks were identified by upstream regulator analysis tool in IPA software.

| TFs | p Value | Z Score | Status | p Value | Z Score | Status | p Value | Z Score | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOXA3 | 1.21E−05 | 2.216 | Activated | 3.78E−06 | 1.678 | – | 6.87E−03 | − | – |

| HNF4α | 6.01E−04 | 2.242 | Activated | 5.42E−08 | 4.086 | Activated | 1.56E−02 | 0.963 | – |

| NR1I2 | 2.35E−07 | 3.542 | Activated | 5.00E−10 | 2.471 | Activated | 5.33E−03 | 1.768 | – |

| NR1I3 | 9.63E−12 | 3.678 | Activated | 1.88E−10 | 3.396 | Activated | 6.41E−04 | 2.39 | Active |

| NR3C1 | 2.07E−05 | 1.982 | – | 8.21E−04 | 2.376 | Activated | 4.06E−03 | 0.348 | – |

| RXRα | 3.21E−08 | 1.451 | – | 4.53E−06 | 2.415 | Activated | 6.29E−03 | – | – |

Discussion

Previous in vitro approaches to examine the DDI potential of rifamycins have either used real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or microarray technologies to quantify changes in the gene expression of DMEs16,20–24. The results from these studies have provided some evidence on DME expression pattern in PHHs, and may differ from a highly sensitive NGS approach25. Moreover, existing evidence on rifabutin and rifapentine DDI potential is limited. We overcame several of these challenges with the use of (1) PHHs from healthy donors free of drug, tobacco, alcohol, and medicine usage (Table S1); (2) the use of NGS technology to precisely quantitate changes in gene expression; and (3) comparison of rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine on a similar platform using equimolar drug treatment concentrations (10 μM) to demonstrate comparative DME gene expression.

Deciphering transcriptome based metabolic responses to a drug in PHHs is an important “in vitro” strategy to identify potential DDIs. In transcriptomic responses, changes in DMEs and drug transporter patterns further influence metabolic pathways, interactive transcriptional networks, and upstream regulators, all of which provide significant information on potential drug interactions and molecular events underlying DME profiles and their associated DDIs. In our experiments, the initial quantitation of intracellular concentrations of rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine and their active desacetyl-metabolites in PHHs has demonstrated the relative metabolic rates of rifamycins in PHHs. We found that the metabolic rates followed a pattern of rifapentine > rifabutin ≥ rifampin, which formed an important basis for downstream transcriptomic studies.

Both rifapentine and 25-desacetyl-rifapentine have antimicrobial properties, which may contribute to its prolonged antimicrobial activity26, and its therapeutic effectiveness has been observed in recent clinical studies27-29. While rifamycins share a structure–activity relationship among themselves, there are some considerable differences observed in their antimicrobial and other pharmacologic properties: (1) rifabutin has enhanced antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium avium and its potency was found to be similar to rifampin against M. tuberculosis30; (2) the half-life (t1/2) of rifabutin (32–67 h) > rifapentine (14–18 h) > rifampin (2–5 h) in the serum of treated TB patients31,32 with the relative protein binding ability of rifapentine (97.7%) > rifampin (≤ 88%) > rifabutin (85%)33–35; (3) maximal concentrations (Cmax) of rifamycins observed in the serum of rifamycin treated TB patients follow a rifapentine (≤ 30 mg/L, 600 mg single daily dose) ≥ rifampin (≤ 20 mg/L, 600 mg) > rifabutin (≤ 0.6 mg/L, 300 mg) pattern with the clinically used doses32 and (4) all rifamycins undergo deacetylation and form ‘deacetyl’ derivatives, but rifampin and rifapentine uniquely undergo hydrolysis and form ‘formyl’ derivatives, whereas rifabutin undergoes hydroxylation and forms ‘hydroxyl’ derivatives. A comparison of transcripts induced in response to each of the rifamycins in PHHs has not been identified to date. This study showed that 126 transcripts were integrally regulated by all rifamycins, and rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine contributed 1.53%, 4.47%, and 1.3% of total transcripts in PHHs, respectively (Fig. 2A). About 1.22%, 4.15%, and 0.99% of total transcripts were uniquely regulated in response to rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine responses in PHHs, respectively. Relatedly, several metabolic pathways were significantly induced by all rifamycins.

In drug metabolism, CYP3A4 is a key common metabolic enzyme involved in clearance of > 80% of currently used therapeutics36. This is the first RNA sequence-based report showing the CYP3A4 induction pattern among rifamycins as rifapentine < rifampin < rifabutin (Table 1). Previously, Dooley et al.37 showed that when midazolam was combined with rifapentine, midazolam had faster clearance rate as compared to midazolam combined with rifampin, potentially due to higher CYP3A4 activity. In contrast, Li et al., showed that comparative induction of CYP3A4 acvtivity among rifamycins was rifampin > rifapentine > rifabutin based on 6ß- hydroxylation of testosterone as an indirect measure of CYP3A4 activity21. Later, Williamson et al. showed a different pattern of rifampin > rifabutin > rifapentine based on in vitro real-time PCR experiments. Our data are consistent with the report from Williamson et al.23, which showed that rifapentine was identified as the weakest CYP3A4 inducer among rifamycins on an equimolar basis. Whether differences in the level of absorption of rifamycin antibiotics in the gut of TB infected persons contribute to the different CYP3A4 induction pattern of rifamycin drugs in “in vivo” studies is unclear.

Consistent with earlier reports, metabolism of melatonin38,39 and bupropion40 were increased, along with acetone and nicotine metabolism, based on rifampin mediated DME expression (Table S3). We found rifapentine to be the weakest inducer of CYP2C8, 3A4, 3A7, and UGT1A4 and 1A5 as compared to rifampin and rifabutin at similar concentrations (10 µM). A previous clinical study by Burman et al.32 showed that the use of a CYP3A4 inhibitor enhanced the bioavailability of rifabutin, whereas the inhibitor could not boost rifampin and rifapentine bioavailability. Based on our study results, rifabutin was the highest inducer of CYP3A4 and is a major pathway involved in its clearance and thereby it’s inhibition may have increased it’s bioavailability.

Healthy volunteer studies of the antiretroviral drug raltegravir in combination with rifapentine, rifampin or rifabutin are consistent with our findings. Combination of raltegravir (400 mg twice daily) with rifapentine (600 mg once daily) showed an decrease in raltegravir’s AUC 0–12 h by 5% as compared to raltegravir alone41. In contrast, both rifampin (600 mg single daily dose) and rifabutin (300 mg single daily dose) reduced raltegravir AUC 0–12 h by 41% and 19% respectively42,43. However, regimens used to either treat or prevent TB often utilize multiple drugs in combination, such as rifampin or rifapentine in combination with isoniazid, making interpretation of possible drug-drug interactions difficult. More so, differences exist in the adminsitration of rifamycins between regimens, including various doses and dosing schedules. Collectively, these differences hinder the ability to directly compare regimens and their effects on DMEs.

Unlike rifampin and rifabutin, rifapentine may not influence a large number of metabolic pathways as it showed a higher specificity among rifamycins. Rifapentine is combined with isoniazid for treatment of LTBI and a one month regimen was shown non-inferior to nine months of isoniazid or four months of rifampin or three months of rifapentine and isoniazid therapy44. In the case of DME inducing ability, all rifamycins induced UGT1A4, 1A5, and SULT2A1. In addition, rifampin and rifabutin combinedly induced UGT1A1 and 1A3, while rifampin induced UGT2B4, 2B17, and 2B15, which indicated their additional influence with potential drug metabolizing pathways as compared to rifapentine (Table S3).

The specific metabolic programs influenced by treatment of PHHs with rifamycins were evident through analysis of interactive transcriptional networks. In our analysis, we identified NF-KB, NCOA, NR1I2, NR1I3 and RXRα TFs as key regulators of a complex network of DMEs and drug transporters. Additional evidence from URA showed the involvement of FOXA3, HNF4α, NR1I2, NR1I3, NR3C1 and RXRα TFs on regulation of CYPs and other key metabolic genes in PHHs. The role of FOXA3 and NR3C1 on controlling the expression of DMEs in PHHs has largely remains unexplored. Though this study has provided a strong evidence on the regulation of above TFs in controlling the expression of DMEs during rifamycin treatment, additional evidence supporting our data may strengthen these findings and fill in the important gaps in DDIs that arise with the use of rifamycins. Though this study has discussed consistency of rifamycin DDI pattern with clinical data on rifamycins and their interactions with raltegravir, additional supportive clinical data may be needed on rifamycin DDIs with various drugs used to treat co-morbidities in TB patients. Future studies may provide additional evidence to show clinical significance of effective therapies designed based on our study to treat co-morbidities in TB patients.

In conclusion, our data has provided evidence on relative changes in DMEs and drug transporter profiles altered in response to rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine treatment. Additionally, this study illustrated the lower interaction potential of rifapentine among rifamycins with concomitant medications such as antiretroviral and anticancer drugs. Finally, it confirms the involvement of FOXA3, HNF4α, NR1I2, NR1I3, NR3C1 and RXRα TFs in regulation of DMEs including CYP3A4.

Materials and methods

Primary human hepatocytes (PHHs)

Human plateable induction-qualified PHHs isolated from three drug/tobacco/alcohol free healthy donors were purchased from Life technologies corporation (Chicago, IL) or Lonza (Chicago, IL) (additional details described in Table S1). Reagents required to culture PHHs were purchased from Life technologies corporation, Chicago, IL unless otherwise noted. Cells were thawed at 37 °C for one minute and were transferred into 50 mL of hepatocyte thawing medium (CAT# CM7500) and the tube was centrifuged at 100 g for 10 min. PHHs were seeded at 0.5 million cells per well density in a collagen coated (12–18 h) six well plate (CAT#A1142802). PHHs were then cultured in Williams E medium without phenol red (CAT#A1217601) supplemented with Hepatocyte thawing and plating supplements (CAT#CM3000) and incubated at 37 °C. Medium was replaced with Williams E medium without phenol red supplemented with Hepatocyte maintenance cocktail (CAT#CM4000) and were incubated for 48 h with daily changes of culture medium before drug treatments.

Drugs, treatments and drug analysis

Rifampin and rifabutin were purchased from US Pharmaceuticals, Rockville, MD and rifapentine was a kind gift of Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France. PHHs were treated with rifampin, rifabutin and rifapentine at 10 µM concentration for 72 h. with the corresponding untreated (negative) and 0.0025% methanol (vehicle) treated controls. We measured intracellular concentrations (ICC) of parent and des-acetyl-metabolites by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectroscopy (LC–MS/MS) as we have previously described45–49.

RNA Isolation, NGS and differential gene expression analysis

Total RNA, was extracted from rifampin, rifabutin, rifapentine and vehicle treated and untreated PHHs using RNeasy fibrous tissue mini kit (Qiagen, Carol Stream, IL) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and as described previously51,52. To quantify copies of transcripts expressed in PHHs in response to rifampin, rifabutin and rifapentine, we performed NGS using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer available at the University of Nebraska Medical center (UNMC)’s genomics core facility at UNMC, Omaha, NE. Complimentary DNA (cDNA) libraries for rifamycin treated PHH samples were constructed using the TruSeq RNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). All samples were subjected to 50-cycle, single-read sequencing in the HiSeq2500 and were demultiplexed using Bcl2Fastq v2.17.1.14 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Short cDNA fragment data were compiled in FASTQ format. Further analysis of FASTQ files were performed in strand NGS software (Agilent technologies, USA). Gene expression levels were calculated using fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) following normalization. RNA sequencing data files and processed transcript expression are available at NCBI GEO (Accession No# GSE139896). The data obtained from sequence analysis were of high quality (> 98.5% perfect index reads or PIR). More than 4 billion sequences were read in a total of 30 samples and with a minimum of 15 million sequence depth per sample (Figure S2). In case of differential gene expression study, the transcripts that were passed through p value significance (< 0.05) and FC (> 1.5) filters were considered as significant changes in gene expression from a total of > 40,000 transcripts expressed in PHHs.

Pathway enrichment analysis

Pathway enrichment data analysis was performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis or IPA (Qiagen Inc., https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuitypathway-Analysis) according to the standard protocols as previously reported50. In this, we overlaid a list of rifamycin RGs on more than 500 cellular and metabolic pathways available in IPA to identify various hepatic and metabolic pathways regulated during rifampin, rifabutin and rifapentine treatments in PHHs as previously described51. UNMC has a license to IPA software and subscribers can use it to generate images of pathways and gene networks that can be published without any consent from Qiagen. IPA provided a list of regulated pathways based on the involvement of differentially expressed transcripts from a particular dataset. ‘Core analysis’ was performed on the list of significantly up and down regulated differentially expressed drug responsive genes (0.05p and 1.5 FC) to interpret biological pathways according to the standard protocol51. We set several parameters, including, ‘p value’ significance, ‘ratio’ of total number of genes involved in a pathway regulated by RRGs to a total number of genes known in a pathway and ‘z score’ that strongly predicts significantly regulated pathways. Pathways that were passed through the filters of < 0.01 p value significance, 0.1 ratio that constitutes to a minimum involvement of 10 percent of differentially expressed genes in a particular pathway to a total number of pathway specific genes and positive activation z score of 2.0 that strongly predict the influence on a pathway were considered as significantly regulated pathways.

Transcriptional network and upstream regulator analysis (URA)

Transcriptional network and functional analyses were generated through the use of IPA (Qiagen Inc., (Qiagen Inc., https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuitypathway-Analysis) according to the standard protocols as previously reported50. In a IPA core analysis of rifampin, rifabutin and rifapentine RGs, we compared rifamycin RG data sets to find a link to each of the drug responsive network on the commonly shared genes. Genes unrelated to metabolic pathways were removed from our analysis. Metabolic networks containing DMEs, drug transporters and TFs were separately analyzed. TFs involved in regulation of transcriptional network operated genes were identified and their significance and targets were identified by URA. URA of transcripts was performed to identify significantly (p = 0.01) regulated TFs either in the list of rifamycin RGs or based on prediction. TFs with significant Z score value (> 2.0) were predicted as activated or inhibited pathways based on the prediction of IPA software.

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant differences in rifampin, rifabutin and rifapentine ICC in PHHs was performed between two groups using a student t test in Prism sofware (Graph Pad Sofware Inc, La Jolla, USA). A difference with > 0.05 p value between the two groups was considered significant. Significance analyses in differential gene expression, pathway and upstream regulator analyses were described in their respective sections above.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by 1K23AI134307-01A1 to A.T.P, NIMH P30 MH062261 and University of Nebraska Collaboration Initiative (2019-2020 RFA) to S.R.D, NIAID R01-AI124965 to C.V.F and NICHD R01-HD085887-01A1 to K.S.S. We acknowledge James Eudy for NGS support, and Drs. Maheswara Reddy Emani and Ashok Reddy Dinasarapu for their suggestions and review of the manuscript.

Authors contribution

S.R.D. conceived, designed, and conducted the study and interpreted the data. S.R.D. performed in vitro experiments in PHHs, extracted RNA, and analyzed NGS data obtained from UNMC genomics core facility using strand NGS and IPA software. A.T.P. analyzed study findings and reviewed the manuscript. C.V.F. provided guidance throughout the study. C.V.F. and K.K.S. were involved in scientific discussions and reviewed the manuscript. T.M.M and L.C.W. performed rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine and their des-metabolite quantitation assays in PHH samples. S.R.D. and A.T.P. wrote the manuscript, which was edited and accepted by all authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shetty Ravi Dyavar, Email: shettyravi.dyavar@unmc.edu.

Anthony T. Podany, Email: apodany@unmc.edu

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-69228-z.

References

- 1.Koch A, Mizrahi V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:555–556. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiberi S, et al. Tuberculosis: progress and advances in development of new drugs, treatment regimens, and host-directed therapies. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:e183–e198. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vento S, Lanzafame M. Tuberculosis and cancer: a complex and dangerous liaison. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:520–522. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70105-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenner L, et al. Tuberculosis and the risk of opportunistic infections and cancers in HIV-infected patients starting ART in Southern Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2013;18:194–198. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ronacher K, et al. Acquired immunodeficiencies and tuberculosis: focus on HIV/AIDS and diabetes mellitus. Immunol. Rev. 2015;264:121–137. doi: 10.1111/imr.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauzullo I, Vullo V, Mastroianni CM. Detecting latent tuberculosis in compromised patients. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2015;28:275–282. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winthrop KL, et al. Tuberculosis and other opportunistic infections in tofacitinib-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016;75:1133–1138. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cakar B, Ciledag A. Evaluation of coexistence of cancer and active tuberculosis; 16 case series. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2018;23:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettit AC, Shepherd BE, Sterling TR. Treatment of drug-susceptible tuberculosis among people living with human immunodeficiency virus infection: an update. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 2018;13:469–477. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regazzi M, Carvalho AC, Villani P, Matteelli A. Treatment optimization in patients co-infected with HIV and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections: focus on drug-drug interactions with rifamycins. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2014;53:489–507. doi: 10.1007/s40262-014-0144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng C, Hu X, Zhao L, Hu M, Gao F. Clinical and pharmacological hallmarks of rifapentine's use in diabetes patients with active and latent tuberculosis: Do we know enough? Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2017;11:2957–2968. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S146506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeCluyse EL. Human hepatocyte culture systems for the in vitro evaluation of cytochrome P450 expression and regulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001;13:343–368. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(01)00135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner RM, Park BK, Pirmohamed M. Parsing interindividual drug variability: an emerging role for systems pharmacology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2015;7:221–241. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Achour B, Al Feteisi H, Lanucara F, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Barber J. Global proteomic analysis of human liver microsomes: rapid characterization and quantification of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2017;45:666–675. doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.074732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallick P, Taneja G, Moorthy B, Ghose R. Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes in infectious and inflammatory disease: implications for biologics-small molecule drug interactions. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2017;13:605–616. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2017.1292251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gufford BT, et al. Rifampin modulation of xeno- and endobiotic conjugating enzyme mRNA expression and associated microRNAs in human hepatocytes. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2018;6:e00386. doi: 10.1002/prp2.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Templeton IE, Houston JB, Galetin A. Predictive utility of in vitro rifampin induction data generated in fresh and cryopreserved human hepatocytes, Fa2N-4, and HepaRG cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011;39:1921–1929. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.040824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park MM, Davis AL, Schluger NW, Cohen H, Rom WN. Outcome of MDR-TB patients, 1983–1993. Prolonged survival with appropriate therapy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996;153:317–324. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.1.8542137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zanger UM, Schwab M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013;138:103–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li AP, Rasmussen A, Xu L, Kaminski DL. Rifampicin induction of lidocaine metabolism in cultured human hepatocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;274:673–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li AP, et al. Primary human hepatocytes as a tool for the evaluation of structure-activity relationship in cytochrome P450 induction potential of xenobiotics: evaluation of rifampin, rifapentine and rifabutin. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1997;107:17–30. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowen EF, Rice PS, Cooke NT, Whitfield RJ, Rayner CF. HIV seroprevalence by anonymous testing in patients with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and in tuberculosis contacts. Lancet. 2000;356:1488–1489. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02876-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williamson B, Dooley KE, Zhang Y, Back DJ, Owen A. Induction of influx and efflux transporters and cytochrome P450 3A4 in primary human hepatocytes by rifampin, rifabutin, and rifapentine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:6366–6369. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01124-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Regazzi M, Carvalho AC, Villani P, Matteelli A. Treatment optimization in patients co-infected with HIV and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections: focus on drug-drug interactions with rifamycins. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2014;53:489–507. doi: 10.1007/s40262-014-0144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Git A, et al. Systematic comparison of microarray profiling, real-time PCR, and next-generation sequencing technologies for measuring differential microRNA expression. RNA. 2010;16:991–1006. doi: 10.1261/rna.1947110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heifets LB, Lindholm-Levy PJ, Flory MA. Bactericidal activity in vitro of various rifamycins against Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990;141:626–630. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mor N, Simon B, Mezo N, Heifets L. Comparison of activities of rifapentine and rifampin against Mycobacterium tuberculosis residing in human macrophages. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2073–2077. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swindells S, et al. One Month of rifapentine plus isoniazid to prevent HIV-related tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:1001–1011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sterling TR, et al. Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:2155–2166. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunin CM. Antimicrobial activity of rifabutin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996;22(Suppl 1):S3–S13. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.Supplement_1.S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birmingham AT, et al. Antibacterial activity in serum and urine following oral administration in man of DL473 (a cyclopentyl derivative of rifampicin) [proceedings] Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1978;6:455P–456P. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.tb04626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burman WJ, Gallicano K, Peloquin C. Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the rifamycin antibacterials. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:327–341. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alghamdi WA, Al-Shaer MH, Peloquin CA. Protein binding of first-line antituberculosis drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00641-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Food and drug administration (FDA) database weblink 1: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/050689s016lbl.pdf

- 35.Food and drug administration (FDA) database weblink 2: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021024s009lbl.pdf

- 36.Li AP, Kaminski DL, Rasmussen A. Substrates of human hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4. Toxicology. 1995;104:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0300-483X(95)03155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dooley KE, et al. World Health Organization group 5 drugs for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis: Unclear efficacy or untapped potential? J. Infect. Dis. 2013;207:1352–1358. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou SF, Liu JP, Chowbay B. Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 enzymes and its clinical impact. Drug Metab. Rev. 2009;41:89–295. doi: 10.1080/03602530902843483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogilvie BW, Torres R, Dressman MA, Kramer WG, Baroldi P. Clinical assessment of drug–drug interactions of tasimelteon, a novel dual melatonin receptor agonist. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015;55:1004–1011. doi: 10.1002/jcph.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung JY, et al. Effects of pregnane X receptor (NR1I2) and CYP2B6 genetic polymorphisms on the induction of bupropion hydroxylation by rifampin. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011;39:92–97. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.035246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiner M, et al. Pharmacokinetic interaction of rifapentine and raltegravir in healthy volunteers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014;69:1079–1085. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wenning LA, et al. Effect of rifampin, a potent inducer of drug-metabolizing enzymes, on the pharmacokinetics of raltegravir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2852–2856. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01468-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brainard DM, et al. Lack of a clinically meaningful pharmacokinetic effect of rifabutin on raltegravir: in vitro/in vivo correlation. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011;51:943–950. doi: 10.1177/0091270010375959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jung YEG, Schluger NW. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2020;33:166–172. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Podany AT, et al. Efavirenz pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in HIV-infected persons receiving rifapentine and isoniazid for tuberculosis prevention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015;61:1322–1327. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winchester LC, Podany AT, Baldwin JS, Robbins BL, Fletcher CV. Determination of the rifamycin antibiotics rifabutin, rifampin, rifapentine and their major metabolites in human plasma via simultaneous extraction coupled with LC/MS/MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015;104:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dyavar SR, et al. Normalization of cell associated antiretroviral drug concentrations with a novel RPP30 droplet digital PCR assay. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:3626. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21882-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dyavar SR, et al. Assessing the lymphoid tissue bioavailability of antiretrovirals in human primary lymphoid endothelial cells and in mice. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019;74:2974–2978. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cirrincione LR, et al. Plasma and intracellular pharmacokinetics of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine in transgender women receiving feminizing hormone therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75:1242–1249. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kramer A, Green J, Pollard J, Jr, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in ingenuity pathway analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:523–530. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dyavar Shetty R, et al. PD-1 blockade during chronic SIV infection reduces hyperimmune activation and microbial translocation in rhesus macaques. J. Clin. Investig. 2012;122:1712–1716. doi: 10.1172/JCI60612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ravi DS, Mitra D. HIV-1 long terminal repeat promoter regulated dual reporter: potential use in screening of transcription modulators. Anal. Biochem. 2007;360:315–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.