Highlights

-

•

What is the primary question addressed by this study? This study analyzes survey data from Scholars Program participants (2010–2018) to identify demographic characteristics, attitudes toward components of the Scholars Program, and behaviors after the program that were independently associated with the decision to pursue fellowship training in geriatric psychiatry.

-

•

What is the main finding of the study? Rating the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP) Scholars Program as important for meeting potential collaborators, maintaining AAGP membership and attending a subsequent AAGP annual meeting were all associated with the decision to pursue fellowship in our final model.

-

•

What is the meaning of the finding? The AAGP Scholars Program plays a role in recruiting trainees into the field of geriatric psychiatry.

Key Words: Geriatric psychiatry, recruitment, medical education, fellowship training

Abstract

Objective

The American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP) Scholars Program was developed to recruit trainees into geriatric psychiatry fellowships and is considered a pipeline for fellowship recruitment. Nonetheless, the number of trainees entering geriatric psychiatry fellowship is declining, making it important to identify modifiable factors that may influence trainees’ decisions to pursue fellowship. We analyzed survey data from Scholars Program participants to identify demographic characteristics, attitudes toward program components, and behaviors after the program that were independently associated with the decision to pursue fellowship.

Methods

Web-based surveys were distributed to all 289 former Scholars participants (2010–2018), whether or not they had completed geriatric psychiatry fellowships. We conducted a hierarchical binary logistic regression analysis to examine demographics, program components, and behaviors after the program associated with deciding to pursue geriatric psychiatry fellowship.

Results

Sixty-one percent of Scholars decided to pursue geriatric psychiatry fellowship. Attending more than one AAGP annual meeting (relative variance explained [RVE] = 34.2%), maintaining membership in the AAGP (RVE = 28.2%), and rating the Scholars Program as important for meeting potential collaborators (RVE = 26.6%) explained the vast majority of variance in the decision to pursue geriatric psychiatry fellowship.

Conclusion

Nearly two-thirds of Scholars Program participants decided to pursue geriatric psychiatry fellowship, suggesting the existing program is an effective fellowship recruitment pipeline. Moreover, greater involvement in the AAGP longitudinally may positively influence Scholars to pursue fellowship. Creative approaches that encourage Scholars to develop collaborations, maintain AAGP membership, and regularly attend AAGP annual meetings may help attract more trainees into geriatric psychiatry.

INTRODUCTION

Demand for geriatric psychiatrists is indisputable, with the number of persons age 65 years and older in the United States projected to increase from 41.3 million in 2012 to 83.7 million in 2050.1 A 2012 Institute of Medicine report estimated that 14%–20% of older individuals suffer from mental health and/or substance use disorders2. Primary care physicians, general psychiatrists, and other clinicians without subspecialization provide the majority of older age mental health care.3 , 4 Clinicians with fellowship training in geropsychiatry and geriatric medicine provide much-needed expertise on complex issues relevant to this population, such as multimorbidity due to co-occurring psychiatric and medical disorders, behavioral symptoms of neurodegenerative disorders, and unique phase-of-life issues, such as retirement, leading to psychosocial stress.5 Yet the number of expert providers in geriatric psychiatry is decreasing.2

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education first approved requirements for geriatric psychiatry fellowships in 1993. The field has since faced a gradual decline in trainee recruitment, with the 2018 Resident/Fellow Census report indicating only 55 of 157 geriatric psychiatry fellowship slots (35.0%) filled.6 This contrasts with fill rates in other Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-accredited psychiatry fellowships, including child and adolescent (78.0%), addictions (64.4%), forensics (57.5%), and consult-liaison (54.2%) psychiatry fellowships.6 Disincentives for pursuing geriatric psychiatry fellowship include stigma towards older patients, lower Medicare reimbursement rates with considerable medical school debt, and a lack of institutional mentorship in medical schools and psychiatry residencies.2 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10

In 1997, the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP) launched Stepping Stones to enhance recruitment into geriatric subspecialty training and provide career development for trainees interested in geriatric psychiatry.11 Stepping Stones evolved into the current AAGP Scholars Program, an annual educational initiative designed to introduce the depth, breadth, and appeal of a geriatric psychiatry career to medical students and residents within the United States and Canada. Selected through a competitive application process, Scholars are awarded a 1-year AAGP membership, free registration to the AAGP annual meeting, and financial support to attend the meeting. During the meeting, Scholars participate in a day of tailored programming and are paired with AAGP-member fellowship-trained mentors. With the guidance of their mentors, Scholars complete a scholarly project, such as a literature review, educational project, quality-improvement initiative, or original research.11

In a prior study,12 we found several advantages of the Scholars Program over Stepping Stones, including greater advancement of trainees’ scholarly work and increased networking opportunities. In the current study, we build on these findings by analyzing survey data from Scholars Program participants (2010–2018) to identify demographic characteristics, attitudes toward components of the Scholars Program, and behaviors after the program that were independently associated with the decision to pursue fellowship training in geriatric psychiatry. The overarching goals of the study were to evaluate the effects of the Scholars Program and hone strategies to enhance recruitment into our field.

METHODS

Participants and Procedure

A 36-item web-based survey, developed in 2007, was distributed to all participants in Stepping Stones, AAGP's first program dedicated to trainee recruitment and career development. The same survey was subsequently distributed in two waves (fall 2016 and fall 2018) to all 289 participants in the Scholars Program (2010–2018). This survey was designed to evaluate demographic characteristics, perceived beneficial components of the program, and professional decisions after the program, including whether participants attended subsequent AAGP annual meetings, remained members of the AAGP, and decided to pursue geriatric psychiatry fellowship. The survey was edited in multiple iterations and with pilot testing. Survey data were collected electronically using a website, SurveyMonkey. Results from the Stepping Stones survey and the first wave of the Scholars Program survey are reported in.12 The current study captures data from two different waves of the Scholars Program survey (2010–2016 and 2017–2018) to provide the most up-to-date information on Scholars’ demographics, perceptions, and professional decisions.

For each wave, invitations were sent to the email addresses participants had on file with the AAGP. If emailed invitations “bounced back,” an Internet search was conducted to attempt to locate the individual's current email address. In the emailed invitation, we assured participants their participation in the survey was voluntary and that individual results would remain separate from identifiers. We encouraged participation in the survey even if participants had not chosen to pursue subspecialty training or were not practicing geriatric psychiatry. Two follow-up emails were sent within two weeks after the initial invitation; attempts to contact then ceased. The Institutional Review Board at Yale University exempted the study from full review.

Outcome and Predictors

Our primary outcome was the decision to pursue geriatric psychiatry fellowship training. Since the survey was fielded to all recent and remote participants in the Scholars Program, some participants were still in training while others had completed training. Thus, the survey included two items on the decision to pursue fellowship: one item asking current trainees, “If still in medical school or residency, do you plan to pursue fellowship training in geriatric psychiatry?” and a separate item asking those who were out of training, “If you have completed residency, did you pursue a fellowship in geriatric psychiatry?” These two items were combined into our dichotomous outcome: 0 = did not or does not plan to complete fellowship and 1 = completed or plans to complete fellowship.

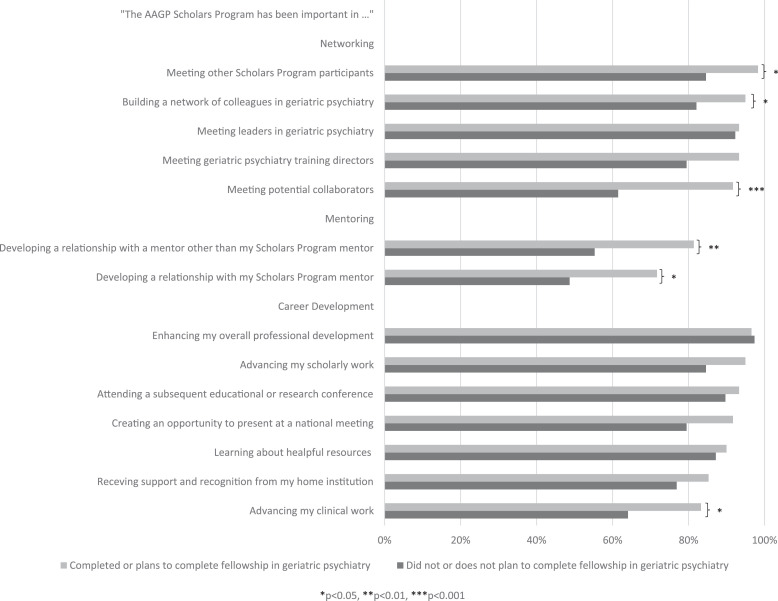

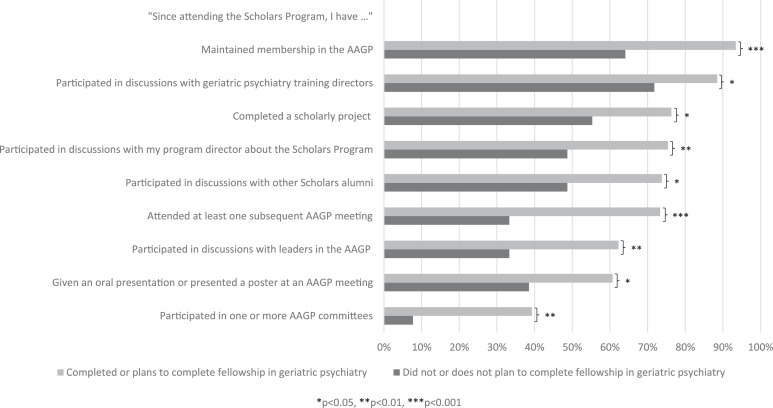

We used three categories of potential predictors for the decision to pursue fellowship training in geriatric psychiatry: demographic characteristics, perceived beneficial components of the program, and behaviors after the program. Demographic characteristics included gender, age (on a continuous scale), whether the participant was an international medical graduate (included because of the rising number of international medical graduates entering geriatric psychiatry6), and whether the participant first attended the Scholars Program as a medical student versus as a resident (included because of previous work suggesting that exposure to geriatric psychiatry earlier in training is associated with greater interest in geriatric psychiatry13). Perceived beneficial components of the program included 14 items (Fig. 1 A) that began with “The Scholars Program has been important in …” followed by each of the components (e.g., mentoring) and a 5-level Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. To improve interpretation and because of skewness toward positive responses, these responses were dichotomized such that 0 = strongly disagree and/or disagree and/or neutral and 1 = agree and/or strongly agree. Finally, behaviors after the program included 9 items (Fig. 1 B) that began with “Since attending the Scholars Program, I have …” followed by the behavior (e.g., attending a subsequent AAGP meeting) and a dichotomous (yes and/or no) response choice.

FIGURE 1A.

Perceived Beneficial Components of the Program and Their Association with Decision to Pursue Fellowship in Geriatric Psychiatry. Components nominally associated with pursuing fellowship in bivariate comparisons are indicated with asterisks. *p<0.05: meeting other Scholars Program participants (Fisher's exact test, 2-sided); building a network of colleagues in geriatric psychiatry (Fisher's exact test, two-sided); developing a relationship with my Scholars Program mentor (χ2 = 5.32, degrees of freedom [df] = 1); advancing my clinical work (χ2 = 4.67, df = 1). **p<0.01: developing a relationship with a mentor other than my Scholars Program mentor (χ2 = 7.66, df = 1). ***p<0.001: meeting potential collaborators (χ2 = 13.31, df = 1).

FIGURE 1B.

Behaviors after the Program and Their Association with Decision to Pursue Fellowship in Geriatric Psychiatry. Behaviors nominally associated with pursuing fellowship in bivariate comparisons are indicated with asterisks. *p<0.05: participated in discussions with geriatric psychiatry training directors (χ2 = 4.51, degrees of freedom [df] = 1); completed a scholarly project (χ2 = 4.69, df = 1); participated in discussions with other Scholars alumni (χ2 = 6.48, df = 1); given an oral presentation or presented a poster at an AAGP meeting (χ2 = 4.69, df = 1). **p<0.01: participated in discussions with my program director about the Scholars Program (χ2 = 7.45, df = 1); participated in discussions with leaders in the AAGP (χ2= 7.99, df = 1); participated in one or more AAGP committees (χ2 = 12.09, df = 1). ***p<0.001: maintained membership in the AAGP (χ2 = 13.87, df = 1); attended at least one subsequent AAGP meeting (χ2 = 15.48, df = 1).

Statistical Analyses

Our analyses proceeded in three steps. First, independent-samples t tests and chi-square tests or Fisher's exact tests, as appropriate, were computed to compare demographic characteristics, components of the program, and behaviors after the program in participants who did and did not decide to pursue fellowship training in geriatric psychiatry. Second, we conducted a hierarchical binary logistic regression analysis to identify demographic characteristics, components of the program, and behaviors after the program that were independently associated with the decision to pursue fellowship. Demographic variables significantly (p<0.05) associated with pursuing fellowship in bivariate analyses were force-entered in Step 1, and those components of the program and behaviors after the program that were nominally associated with pursuing fellowship (p<0.05) were entered in Step 2 using the Forward Wald stepwise estimation approach. This more inclusive approach allowed us to consider a broader range of potential predictors of the decision to pursue fellowship in a multivariable regression model; further, we chose to use stepwise estimation because of the large number of significant components and behaviors that met the nominal significance threshold in bivariate analyses. Third, we used R to conduct a relative importance analysis,14 which assesses the relative variance explained of each independent variable in the final logistic regression model.

RESULTS

Of the 289 Scholars Program participants, 100 (34.6%) responded to the survey. Of those who responded, 61 (61.0%) reported they completed a fellowship in geriatric psychiatry or were planning to complete a fellowship. Table 1 shows demographic characteristics of the participants. Figs. 1A and 1B show perceived beneficial components of the program and behaviors after the program, respectively, and their association with the decision to pursue fellowship training in geriatric psychiatry.

TABLE 1.

Participant Demographics and Their Association With Decision to Pursue Fellowship in Geriatric Psychiatry

| Total Sample(N = 100)M (SD) or N (%) | Completed or Plans to Complete Fellowship in Geriatric Psychiatry(N = 61)M (SD) or N (%) | Did Not or Does Not Plan to Complete Fellowship in Geriatric Psychiatry(N = 39)M (SD) or N (%) | Test of Differencet or χ2(1), p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.6 (3.8) | 32.9 (3.6) | 32.0 (4.2) | 1.14, 0.26 |

| Female sex | 67 (67.0) | 45 (73.8) | 22 (56.4) | 3.24, 0.072 |

| First attended as a medical student (versus resident) | 35 (35.0) | 16 (26.2) | 19 (48.7) | 5.29, 0.021 |

| International medical graduate | 17/99 (17.4) | 12/59 (20.3) | 5 (12.8) | 0.93, 0.336 |

Note: The significant predictor of completing or planning to complete fellowship is shown in bold.

Step 1 of the hierarchical logistic regression model included forced-entry of one demographic variable—first attending the Scholars Program as a medical student. However, this did not remain significant in Step 2 (Wald χ2 = 2.25, p = 0.134; odds ratio [OR] = 0.45, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.16-1.28). One beneficial component of the program and two behaviors after the program were significantly associated with the decision to pursue fellowship in the final model—rating the Scholars Program as important for meeting potential collaborators (Wald χ2 = 5.89, p = 0.015; OR = 5.55, 95%CI = 1.39–22.16); attending more than one AAGP annual meeting (Wald χ2 = 8.97, p = 0.003; OR = 4.74, 95%CI = 1.71–13.12); and maintaining membership in the AAGP (Wald χ2 = 5.83, p = 0.016; OR = 5.54, 95%CI = 1.38–22.23). Nagelkerke's R2 for the full model was 0.38.

Relative importance analysis results revealed that attending more than one AAGP meeting explained 34.2% of the variance in the decision to pursue fellowship training in geriatric psychiatry, maintaining membership in the AAGP explained 28.2% of the variance, and rating the program highly for meeting potential collaborators explained 26.6% of the variance, whereas being a medical student participant explained only 10.9% of the variance.

DISCUSSION

At a time when the population of older adults in the United States is rapidly expanding while numbers of geriatric psychiatry fellowship applicants are dwindling, it is crucial to identify modifiable factors that may influence a trainee to pursue subspecialty training in geriatric psychiatry. The AAGP Scholars Program has an explicit focus on recruitment into geriatric psychiatry fellowship.11 , 12 This study surveyed all 2010–2018 Scholars Program participants to evaluate what percentage decided to pursue fellowship and which demographic characteristics, components of the program, and behaviors after the program were associated with the decision to pursue fellowship. Most respondents (61.0%) did decide to pursue fellowship training in geriatric psychiatry. One component—rating the Scholars Program important for meeting potential collaborators—and two postprogram behaviors—maintaining AAGP membership and attending a subsequent AAGP annual meeting—were associated with the decision to pursue fellowship in our final model. While medical student Scholars were less likely to decide to pursue fellowship than psychiatry resident Scholars in bivariate comparisons, training level was not associated with the decision to pursue fellowship in our final model, contrary to previous work that evaluated interest in geriatric psychiatry among psychiatry residents.13 This study revealed the importance of the AAGP to the pipeline mission of the Scholars Program. In fact, the final three significant predictors all indicated that greater involvement in AAGP may positively influence the decision to pursue fellowship training in geriatric psychiatry.

While all Scholars are given a one-year complimentary AAGP membership, we found that maintaining membership was independently associated with the decision to pursue fellowship training in geriatric psychiatry. This is not surprising, given the robust opportunities for exposure to geriatric psychiatry, mentorship, and networking that exist within the AAGP. In addition to joining the Members-in-Training Caucus and keeping connected to fellow Scholars alumni, trainees are welcome to participate in AAGP committees (Research, Teaching and Training, Clinical Practice) and caucuses (e.g., Public Policy, Diversity, International Medical Graduates). These groups meet at the annual meeting and have active email listservs with ongoing opportunities for collaboration. In this way, trainees discover and participate in AAGP activities and initiatives and foster valuable professional connections for assistance with career planning, research collaboration, and organizational engagement. As members, trainees also receive a subscription to the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, the highest-impact journal in geriatric psychiatry.

Maintenance of AAGP membership likely provides trainees a glimpse into the window of a potential “professional home” or “professional family.” A professional home for physicians is described as a group which provides a sense of community, of belonging, and of unified purpose.15 Psychiatric organizations in particular are highlighted as serving as “professional families” and thus influencing professional development for trainees and early career psychiatrists.16 Many AAGP members consider the AAGP their professional family, which includes beloved colleagues who share a commitment to caring for older adults with mental health needs; like-minded educators passionate about teaching; inspiring researchers providing evidence-based data for the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in late life; and kindred spirits advocating for older adults with mental disorders.17 In the authors’ experience of over 70 combined years of AAGP membership, many attendees develop lifelong relationships, both professional and personal, and look forward to reuniting annually to learn from one another while continuing to innovate for patient care and professional development. This warm sense of community is palpable by trainees and likely influences interest in pursuing fellowship training.17

Returning to a subsequent AAGP annual meeting was also independently associated with the decision to pursue fellowship training. The direction of causality for both AAGP-related items remains unclear. Those who maintain membership or return may seek greater exposure to geriatric psychiatry to assist in their career decision-making process, but Scholars may maintain membership or return because they are already committed to fellowship training. Regardless, our findings support efforts to encourage trainees to attend subsequent AAGP meetings. The current Scholars Program has one such yearly mechanism: awardees are provided an opportunity to return to a meeting for the Honors Scholars Alumni symposium. Each Scholar is encouraged to submit an abstract of their scholarly work for possible selection; a committee determines which abstracts are chosen. Currently, 3–4 trainees are selected to present. Each receives meeting registration and a stipend (approximately $400) to defray travel costs.

Meeting potential collaborators during the Scholars Program was another factor correlated with pursuing fellowship training. Two aspects of the existing program are designed to help Scholars meet collaborators: the assignment of AAGP mentors and the requirement for Honors Scholars (PGY1-3 residents) to complete a scholarly project. The Scholars Program carefully matches trainees with assigned AAGP member mentors based on common career interests; the “matching” process involves the completion of a “career interest” survey by both parties. Each mentor-mentee dyad is required to complete a scholarly project over the course of the subsequent training year. This mentorship relationship is honed via email communication in advance of the meeting, a mentor-mentee luncheon the day of the program, and ongoing communication beyond the meeting. However, we should note that survey items on the quality of mentoring relationships and the completion of the scholarly project requirement were not significant predictors of fellowship training in our final model. These results are somewhat conflicting, making it challenging to discern the underlying meaning. We suspect the myriad of informal greetings and conversations with AAGP members at large group gatherings such as the opening reception and Scholars reception, the visible accessibility of our leadership, and the various casual introductions that occur between session attendance contribute to trainees’ experiences at the annual meeting. These informal connections, known to so many of us who have been AAGP members for years, were not captured as part of the Scholars survey, which in retrospect is a shortcoming of the survey. Nonetheless, similar to our other findings in this study, the finding again highlights the importance of involvement in the AAGP for Scholars to pursue fellowship training. A future survey could include additional items on the types of collaborations Scholars developed.

In addition to supporting aspects of the existing program, this study suggests several ways the Scholars Program could be expanded or modified to further enhance recruitment. First, since most Scholars decide to pursue fellowship, increasing the number of Scholars accepted may provide a short-term response to assist in recruiting. However, the rate-limiting factor for accepting more Scholars is financial. Funds for the Scholars Program are generated entirely by donation; between the years 2012-2020, donations ranged from $65,182 to $104,979. The primary source of these monies were member donations, and in 2018, 2019, and 2020 a private risk management company donated $5,000-7,500 annually. AAGP members affiliated with institutions often pool monies to fund a $2,500 Honors Scholarship, and many AAGP members create scholarships in honor of a family member, colleague, or friend. Despite this outstanding generosity, the program does not have funds to accept all qualified applicants. From 2012 to 2020, the program's average acceptance rate was 63%, with a high of 86% in 2016 and low of 40% in 2018 (during the Hawaii conference when the program received a record 98 applicants). Excluding the Hawaii conference, the number of applicants between 2012 and 2020 was 43–76. The breakdown for acceptance to the program by year of training was as follows: 84% PGY3s, 50% PGY1 and/or PGY2s, and 59% medical students.

A multi-pronged approach is required to expand funding for the Scholars Program. Examples include: continue to inspire past donors to participate through a “dialing for dollars campaign,” which was implemented by Scholars Program committee members and other AAGP leaders in 2017; increase the number of organizational contributors by utilizing current AAGP onsite meeting vendors and AAGP member contacts with private companies; and consider an increase in the cost of meeting registration to create a steady donation stream annually. A several-year commitment of a funding source would benefit the program in terms of planning and determining the feasibility of asset redistribution to maximize trainee numbers, encourage meeting repeat attendance, and perhaps provide an educational seminar for mentors to inspire interest and mentorship training among this important subgroup of AAGP members.

Another option to enhance recruitment is to modify the existing program. Our results suggest that greater involvement in the AAGP is associated with matriculation into geriatric psychiatry fellowship. Therefore, a different funding allocation could enable more trainees to attend the AAGP annual meeting each year. Currently, each Honors Scholar receives full funding, totaling approximately $2,500, which covers meeting registration, AAGP membership, hotel accommodations, travel, and Scholars events (breakfast, mentor lunch, donor reception). Each medical student (General Scholar) receives partial funding, which includes meeting registration, AAGP membership, approximately $800 to cover travel and hotel expenses, plus attendance at the Scholars events. The program could offer partial scholarships instead of full funding to PGY1-3 Honors Scholars, thereby increasing the number of attendees.

Other modifications may increase the number of Scholars who maintain membership in the AAGP, make return visits to the AAGP annual meeting, and engage with potential collaborators. Honors Scholars are required to work on a research, educational, or clinical/quality-improvement scholarly project, and 3–4 Honors Scholars are invited to return to the following year's annual meeting to present at an Honors Scholar Alumni symposium. Despite the mandatory expectation that all participate in a project, only 1/3 of Honors Scholars submit an abstract for presentation consideration. The Scholars Program planning committee intends to invite Honors Scholars Alumni applicants to complete a poster if their abstract is not selected for the symposium. The program could incentivize this activity by providing a small stipend for those participating in the poster presentation session. Additional options include the provision of complimentary meeting registration for the year after participating in the program, and the development of an online forum to maintain contact with Scholars during the interval between meetings. In the era of COVID-19 driven tele-meetings, an interactive remote platform is an ideal way to promote further contact between Scholars and the AAGP. A webinar for PGY-3 Scholars was successfully implemented after the cancellation of the 2020 AAGP annual meeting due to COVID-19; future webinars with Scholars are currently in planning stages. Finally, mentors should take a more active role in ensuring scholarly work completion and abstract submission with mentees, emphasizing both the importance of collaboration and continued AAGP engagement as mechanisms to partially address pipeline deficits.

The limitations of the study are noteworthy. Given we had 27 candidate variables, the chance for a Type I error is high. And while only 34% responded to our survey, this response rate is consistent with other survey-based research13 but does limit the generalizability of our findings. For example, some Scholars who did not complete the survey may have pursued fellowship for reasons other than those found in our study. Indeed, since our survey was disseminated by AAGP staff, those who did not continue to participate in AAGP may have been less likely to respond, potentially generating a nonresponse bias in the direction of showing greater importance for AAGP involvement in the decision to pursue fellowship. In addition, while we explicitly requested survey participation from respondents regardless of whether or not they pursued fellowship, selection bias may also be a possibility. Data on gender, age, and other demographics was not collected from Scholars as part of the program application or evaluation processes, thus preventing us from comparing survey respondents to non-respondents. We also did not have a sufficient sample size to test whether predictors of pursuing fellowship may differ between psychiatry residents and medical students. In addition, some Scholars were surveyed soon after program participation and may not have made a final decision about fellowship training. Lastly, while demonstrating that maintaining AAGP membership, returning for a subsequent annual AAGP meeting, and meeting with potential collaborators are all factors associated with a trainees’ decision to pursue fellowship, it is unclear if these factors would influence career decisions if provided independent of the Scholars Program. Future studies may include follow up with participants to verify the decision to pursue fellowship training and studies with larger samples could assist in determining differences and similarities in predictors between psychiatry residents and medical students in the decision to pursue fellowship training.

Notwithstanding these limitations, results of the current study suggest that the AAGP Scholars Program continues to serve an important role in addressing the pipeline deficit in geriatric psychiatry. Even for those trainees who do not pursue a career in geriatric psychiatry, participation in the program provides an important platform to promote the integration of care for older adults into other types of practice, whether within psychiatry or other medical specialties. The professional value of the organization to both members and trainees is clear. Future studies should evaluate the influence of the Honors Scholars Alumni session on the decision to pursue fellowship training, and survey current AAGP members to determine reasons for pursuing fellowship, the influence of the Scholars Program on career planning, and future directions for recruitment into geriatric psychiatry.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Authors listed for this manuscript (Conroy, Yarns, Wilkins, Lane, Zdanys, Pietrzak, Forester, and Kirwin) contributed to authorship in the following manners:

-

•

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

-

•

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

-

•

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

-

•

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

REQUIRED DISCLAIMER

These contents do not represent the views of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

The authors wish to thank Christopher Wood and Victoria Cooper for their assistance in distributing the survey. Dr. Yarns was supported by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (grant number CX001884). Dr. Forester is supported by grants from Biogen, Eli Lilly, National Institutes of Health, Spier Family Foundation, and the Rogers Family Foundation, which are outside of this submitted work.

The authors report no conflicts with any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Ortman JM., Velkoff VA, Hogan H. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2014. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States, Current Population Reports; pp. 25–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. The mental health and substance use workforce for older adults: in whose hands? J Eden, K Maslow, M Le, et al. (Eds.), The Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce for Older Adults: In Whose Hands?, National Academies Press, Washington, DC (2012). [PubMed]

- 3.Cohen D., Cairl R. Mental health care policy in an aging society. In: Levin B.L., Petrila J., editors. Mental Health Services: A Public Health Perspective. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 301–324. Eds. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C. Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1455–1462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tampi RR, Zdanys KF, Srinivasan S. Advice on how to choose a geriatric psychiatry fellowship. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27:687–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychiatric Association . 2019. 2018 Resident / Fellow Census. Available at https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Residents-MedicalStudents/Residents/APA-Resident-Census-2019.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juul D, Colenda CC, Lyness JM. Subspecialty training and certification in geriatric psychiatry: a 25-year overview. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medscape: Residents salary & debt report 2018. (online). Available at: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-residents-salary-debt-report-6010044#13. Accessed February 8, 2020.

- 9.Lehmann SW, Blazek MC, Popeo DM. Geriatric psychiatry in the psychiatry clerkship: a survey of current education practices. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39:312–315. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0316-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkins KM, Blazek MC, Brooks WB. Six things all medical students need to know about geriatric psychiatry (and how to teach them) Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:693–700. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins KM, Forester B, Conroy M. The American association for geriatric psychiatry's scholars program: a model program for recruitment into psychiatric subspecialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:688–692. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0704-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkins KM, Conroy ML, Yarns BC. The American association for geriatric psychiatry's trainee programs: participant characteristics and perceived benefits. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.03.002. (e-published ahead of print) March 7;S1064–7481(20)30247–5. doi: 10.1016/j.japgp.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rej S, Laliberte V, Rapoport MJ. What makes residents interested in geriatric psychiatry? A Pan-Canadian online survey of psychiatry residents. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:735–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tonidandel S, LeBreton JM. Determining the relative importance of predictors in logistic regression: an extension of relative weights analysis. Organ Res Methods. 2010;13:767–781. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batlivala SP. Why early career cardiologists should establish a professional home. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2554–2555. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weerasekera P. Psychiatric organizations: influencing professional development. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31:89–90. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.31.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sewell DD. The American association for geriatric psychiatry: my professional family. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31:103–104. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.31.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]