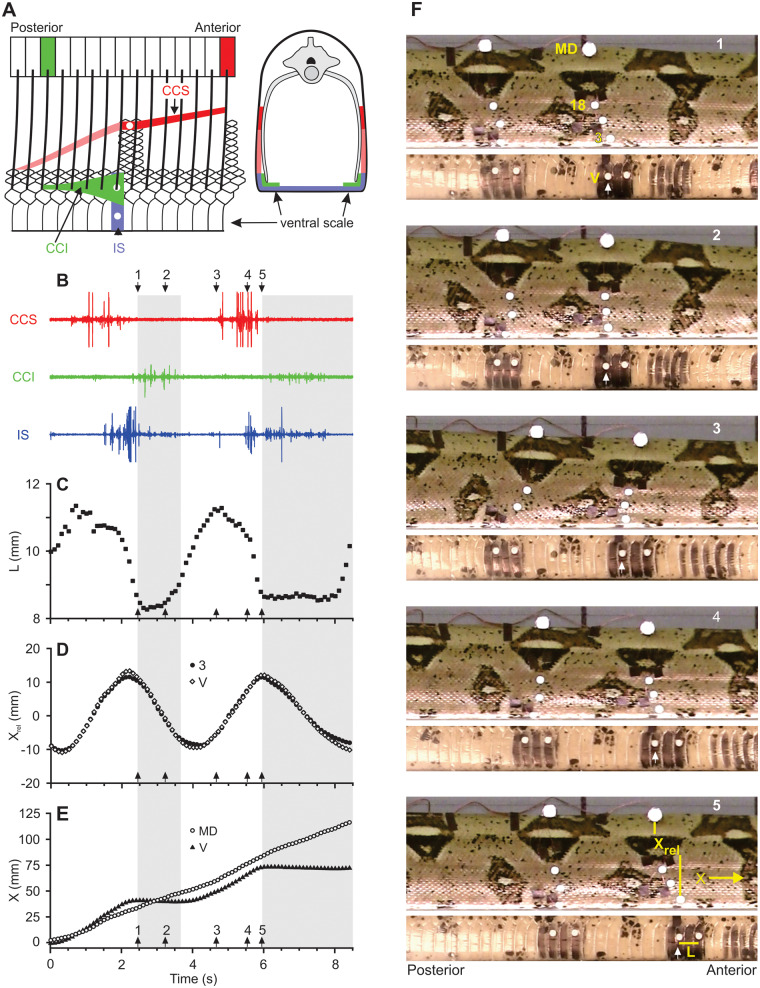

Fig. 1.

Muscles and movements involved in the rectilinear locomotion of a boa constrictor. (A) Schematic views of muscles for which red, green, and blue indicate the contractile tissue of the CCS, CCI, and interscutalis (IS) muscles, respectively. The lighter shade of red indicates less-mobile fibers of the CCS that are firmly connected to the skin along their entire length. The left image is an internal view of the left side of the snake, and the right image is a cross-section. The thick oblique lines indicate ribs, and the colored rectangles indicate the vertebrae of origin for the costocutaneous muscles that act on a single longitudinal location. Unlike the intact snake, the ventral skin is peeled back into a parasagittal plane so that the mid-ventral line is at the bottom of the figure. White circles indicate approximate locations for recording electrodes. As shown at right, the entire width of the ventral scale and the first two dorsal scale rows on both sides of the snake usually contact the ground. EMGs of muscle activity (B) and corresponding kinematics including the length of the ventral skin (C) and the longitudinal positions of landmarks (MD = mid-dorsal, 3 = third dorsal scale and V = ventral scale) relative to a mid-dorsal point (D) and a fixed frame of reference (E). Values of Xrel for the ventral (V) and third dorsal (3) scales have been standardized to a mean value of 0 (D).The gray areas in (B–E) indicate static contact between the ventral skin and the ground as well as some slight backward slipping. Video images of the right side of the snake (top) and ventral scales (bottom) of the snake for the same data as shown in (B–E) (F). Adapted from Newman and Jayne (2018). See supplementary video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wwHkAMo-Mj0.