Abstract

The physical and chemical properties of typical nitrate energetic materials under hydrostatic compression and uniaxial compression were studied using the ReaxFF/lg force field combined with the molecular dynamics simulation method. Under hydrostatic compression, the P–V curve and the bulk modulus (B0) obtained using the VFRS equation of state show that the compressibility of the three crystals is nitroglycerine (NG) > erythritol tetranitrate (ETN) > 2,3-bis-hydroxymethyl-2,3-dinitro-1,4-butanediol tetranitrate (NEST-1). The a- and c-axis of ETN are easy to compress under the action of hydrostatic pressure, but the b-axis is not easy to compress. The b-axis of NEST-1 is the most compressible, while the a- and c-axis can be compressed slightly when the initial pressure increases and then remains unchanged afterward. The a-, b-, and c-axes of NG all have similar compressibilities. By analyzing the change trend of the main bond lengths of the crystals, it can be seen that the most stable of the three crystals is the N–O bond and the largest change is in the O–NO2 bond. The stability of the C–O bond shows that the NO3 produced by nitrates is not from the C–O bond fracture. Under uniaxial compression, the stress tensor component, the average principal stress, and the hydrostatic pressure have similar trends and amplitudes, indicating that the anisotropy behaviors of the three crystals ETN, NEST-1, and NG are weak. There is no significant correlation between maximum shear stress and sensitivity. The maximum shear stresses τxyand τyz of the ETN in the [010] direction are 1.5 GPa higher than τxz. However, the maximum shear stress of NG shows irregularity in different compression directions, indicating that there is no obvious correlation between the maximum shear stress and sensitivity.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the main research on energetic materials has focused on the thermal decomposition mechanism,1−4 “hot spot” hypothesis,5 impact explosion,6,7 laser ignition,8−10 and so on. Pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN, C(CH2ONO2)4) is widely used in military and civilian applications as a typical nitrate energetic material.11 The impact of PETN on anisotropy has attracted people’s interest and achieved many research results.12−18 Dick12 first found that the impact initiation of PETN strongly depends on the orientation of the crystal axis relative to the direction of impact, that is, PETN is sensitive to the impact in the [110] and [001] directions rather than in other directions. Dick et al.13−16 proposed the steric hindrance model, through experiments and calculations, to explain the impact of PETN on anisotropy. This model pointed out that there were available sliding systems in the direction of impact that were insensitive to the initiation of impact. These systems could reduce the shear stress of shock waves due to transmission. The lack of available sliding systems causes the block in the insensitive direction. However, subsequent studies confirmed that the model had failed to expand to other energetic materials.17,18 With the continuous update of the synthesis technology of energetic materials,19 Klapötke et al.20 synthesized PETN analogs by the nitrification reaction of tetramethylsilane in nitric acid, Si–PETN(Si(CH2ONO2)4), that is, substituting the C-atom located at the center of PETN with the Si atom. Si–PETN has a much higher sensitivity than PETN, slight friction can lead to an explosion, and the extremely high sensitivity of Si–PETN makes it difficult to study its sensitivity and other properties by experimental methods.21−23 Liu et al.,24 through the method of density functional theory, predicted the possible chemical reaction path of the single-molecule Si–PETN and concluded that the cause of the high sensitivity of Si–PETN was the generation of low-energy barriers and highly heating Si–O bonds.

It can be seen from the very high sensitivity of Si–PETN that changing the molecular structure will have a great influence on the molecular properties. At present, the unified relationship between the crystal structure, molecular frame, and sensitivity has not yet come into consistent conclusion.25,26 Kamlet et al.27 have put forward a unique theory in terms of the structure, sensitivity, and thermal stability of organic highly explosive materials. However, the latest studies show that there is no single universal relationship between the molecular structure and initiative reactivity.28 Common nitrate energetic materials similar to PETN structures are erythritol tetranitrate (ETN, chemical formula (CH2ONO2)2(CHONO2)2),29 NEST-1 (2,3-bis-hydroxymethyl-2,3-dinitro-1,4-butanediol tetranitrate, chemical formula (CH2ONO2)4(CNO2)2),30 nitroglycerine (NG, chemical formula H(CONO2)(CH2ONO2)2),31 and so on. The study on ETN began to increase due to the large-scale industrial production of meso-erythritol,32 ETN’s precursor, as a sweetening agent. ETN can be made by the nitrification of acetyl nitrate.33,34 Oxley et al.35 thought that ETN and PETN have the same number of nitro groups and oxygen balance; PETN can be replaced in some formulations with ETN. Furman et al.36 used the symmetric plate impact method to study the physicochemical phenomena under the impact of ETN with nanoholes and pointed out that the decomposition mechanism of the condensed ETN followed the monomolecular path, which was consistent with studies from Oxley et al.37 NEST-1 has similar sensitivity30 to PETN; Landerville et al.38 predicted the isothermal fluid static state equation of NEST-1 by DFT, which was well consistent with the experiment. NG has been used especially as an active ingredient in the manufacture of explosives, commonly used in construction and demolition industries. Waring et al.39 studied the thermal decomposition of vapor and liquid NG in a certain temperature range and pointed out that the reaction rate significantly changed with the ratio of nitroglycerin mass to reactor volume, and the elimination reaction of NO2 was the initial reaction path.

The above studies showed that ETN, NEST-1, and NG have similar structures to PETN. Thermodynamic and chemical properties similar to PETN were also obtained, but the relationship between the molecular structure and the physicochemical properties of molecules was still unclear. This paper, using ETN, NEST-1, and NG as the research object, simulated the physicochemical properties presented under loading conditions of hydrostatic compression and uniaxial compression using the ReaxFF/lg force field combined with the molecular dynamics method to provide references for problems of the synthesis of energetic materials.

2. Simulation Details

The ReaxFF40 reaction force field based on the first principle can be used under extreme conditions to describe the formation and fracture of the intermolecular bonds of energetic materials41,42 under near-real conditions through the relationship between bond length, bond level, and bond energy as well as the dynamic transfer of charges between atoms. ReaxFF/lg43 added a description of the London dispersion force on the basis of ReaxFF, that is, amending the long-range interaction force between molecules to more accurately describe the structure and density of molecular crystals. The calculated crystal structure and equation of states showed good consistency with the experimental results.

To obtain a higher computational accuracy44 and fully observe the physicochemical properties of the three molecular structures under the loading conditions of hydrostatic compression and uniaxial compression, 3 × 8 × 3, 5 × 2 × 5, and 5 × 3 × 6 supercells were constructed for ETN, NEST-1, and NG, respectively, to obtain the approximate atomic number and volume of the three structures (see details in Supporting Information Figure S1). Table 1 shows the specific parameters of the model, including lattice parameters and amounts of molecules and atoms.

Table 1. The detailed information of ETN, NEST-1, and NG supercell.

| ETN |

NEST-1 |

NG |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| supercell | 3 × 8 × 3 | 5 × 2 × 5 | 5 × 3 × 6 | ||||||

| lattice parameters | a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) |

| 48.25 | 41.77 | 40.14 | 41.20 | 46.77 | 39.43 | 45.33 | 41.58 | 41.32 | |

| α (deg) | β (deg) | γ (deg) | α (deg) | β (deg) | γ (deg) | α (deg) | β (deg) | γ (deg) | |

| 90 | 116 | 90 | 90 | 114 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | |

| amounts of molecules | 288 | 200 | 360 | ||||||

| amounts of atoms | 7488 | 7200 | 7200 | ||||||

Figure 1 shows a monomolecular model of the three structures. The training set of the ReaxFF/lg force field did not contain the three structures of ETN, NEST-1, and NG, so the applicability of the ReaxFF/lg force field needed to be verified. The super crystal cell was structurally optimized by energy minimization; then the system was placed in the NVT ensemble (300 K) running 10 ps, consequently running 40 ps in the NPT ensemble (300 K, 0 GPa) to optimize atomic coordinates. After optimization, the densities of ETN, NEST-1, and NG structures were 1.786, 1.872, and 1.743 g cm–3, respectively, which were close to experimentally measured densities29−31 of 1.773, 1.917, and 1.846 g cm–3, respectively. The measured lattice constant was consistent with the experimental value (see details in Supporting Information Table S1), proving that the ReaxFF/lg force field had good mobility and could be used to research on ETN, NEST-1, and NG.

Figure 1.

Single-molecule model of ETN (a), NEST-1 (b), and NG (c). Single-cell model of ETN (d), NEST-1 (e), and NG (f). C, H, O, and N are presented by gray, white, red, and blue balls, respectively.

Simulate the hydrostatic compression of ETN, NEST-1, and NG, compressing their super crystal cells from V/V0 = 1.00–0.60, where V0 is the predicted volume below zero pressure. In each compression step, the shape and atomic coordinate of the unit crystal cell were allowed to relax without symmetry constraints at a constant volume. Uniaxial compression was done in three directions: [100], [010], and [001]. For each compression direction, the components of the lattice vector were compressed from V/V0 = 1.00–0.70. During each compression process, only an atomic coordinate offset was allowed, while the crystal cells were fixed. The simulation process uses conditions of the periodic boundary. The simulations were performed using ReaxFF/lg potential in a large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator45,46 with a time step of 0.1 fs.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hydrostatic Compression

At 300 K, under hydrostatic compression, the P–V curve of ETN, NEST-1, and NG is shown in Figure 2. When V/V0 = 0.6, the hydrostatic pressure of NG was up to 30 GPa, which is similar to the pressure of PETN blast at the CJ point.47 For the same amount of compression, the hydrostatic pressure of ETN was more than 30 GPa. Fedorov et al.48 obtained similar results when calculating the hydrostatic compression of ETN and PETN using the first principle. The hydrostatic pressure of NEST-1 was always very high; when V/V0 = 0.6, the hydrostatic pressure was up to 44 GPa, indicating that NEST-1 was the most difficult to compress in the three crystals.

Figure 2.

P–V curve of ETN, NEST-1, and NG under hydrostatic compression at T = 300 K.

The volume modulus (B0) of the crystal and the first derivative (B′0) of the volume modulus to the pressure could be obtained by fitting of the P–V curve. The bulk modulus is used to characterize the ability of a material to resist deformation under external pressure.49 For energetic materials, volume modulus describes the compressibility of materials, which is related to the impact sensitivity of materials. There are two common ways to fit the P–V curve: the third-order Birch–Murnaghan (BM)50 equation (formula 1) and the Vinet–Ferrante–Rose–Smith (VFRS)51 equation (formula 2).

| 1 |

| 2 |

where B0 is the volume modulus, V is the compressed volume, V0 is the initial volume, and B′0 is the first derivative of B0 to the pressure P. This paper uses the VFRS equation to fit the P–V curves of the three crystal forms. The fitted curve is the solid line in Figure 2. B0 and B′0 obtained from the fitting are shown in Table 2 (this work). It can be known from the PETN data in Table 2 that for the same state equation (BM), the obtained B0 and B′0 are also quite different. This is because the result of the fitting depends on the range of the fitted data and the number of data points.54 The results obtained will vary greatly depending on the value range. This is because the result of fitting depends on the range of the fitted data and the amount of the data points, so the results from different ranges of values can vary greatly. Because B0 is the bulk modulus at atmospheric pressure, the pressure range for fitting chosen in this paper is (0 GPa, 10 GPa). Different numbers of data points are selected for multiple fittings, and the average values of B0 and B′0 are obtained. The order from small to large of volume modulus of the three crystals is B0 NEST-1 > B0 ETN > B0 NG, indicating that the compressibility of the three crystals is NG > ETN > NEST-1, that is, NG can be most easily compressed and NEST-1 is the most stable, which is also consistent with the fact that the previous P–V curve in the NEST-1 hydrostatic pressure is always high. Energetic materials and materials with a higher volume modulus are not easy to deform and react chemically under pressure.

Table 2. Bulk modulus B0 and its pressure derivative B′0 obtained by the EOS.

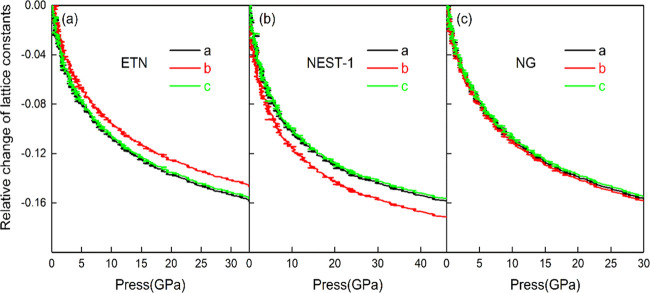

The three crystals have different compressibilities, which is mainly related to the molecular configuration and arrangement of crystals. Figure 3 shows the changing curves of the lattice constant of the three crystals under hydrostatic pressure. The a- and c-axis of ETN are easy to be compressed under hydrostatic pressure, while the b-axis is not easy to be compressed. The b-axis of NEST-1 is the easiest to be compressed, while the a- and c-axis can be compressed slightly when the initial pressure increases and then remains unchanged. The a-, b-, c-axes of NG have similar compressibilities.

Figure 3.

Relative change of lattice constants of ETN (a), NEST-1 (b), and NG (c) under hydrostatic compression.

Figure 4 shows the curve of the key bond length with the compression ratio change in the three crystals, and the corresponding bond length can be found in Figure 1. To get more general results, the similar bonds in the crystal were averaged. It shows that the most stable bond in the three crystals is the N–O bond and the O–NO2 bond has the largest amplitude of variation. Hiskey et al.55 pointed out that the first step of thermal decomposition of the nitric ester is the cleavage of the O–NO2 bond to form NO2. The C–C bond corresponding to the red icon is the C–CH2ONO2 bond, which also shows a larger change than the other bonds. The unique bond of NEST-1 is C–NO2, presenting pretty high compressibility (pink line in Figure 4b). Comparing Figure 4a,c, we find that the C–H bond located on the main chain is more active than the C–H bond in CH2. The C–O bonds in the three crystals show good stability, which also shows that NO3 generated by the nitrate energetic materials is not from C–O bond breakage.

Figure 4.

Bond lengths of ETN (a), NEST-1 (b), and NG (c) under hydrostatic compression. The bonds within a molecule are indicated in Figure 1. The O–NO2 bond length is the average of the sum of O–NO2 bond lengths in the crystal. The ETN and NEST-1 molecules have four O–NO2 bonds, and the NG molecule has three O–NO2 bonds. The N–O bond is in the NO2 radical.

3.2. Uniaxial Compression

The properties of energetic materials in uniaxial compression are particularly important for the plastic deformation and mechanical chemical reactions of energetic materials. Stress tensor is used to describe anisotropic response under the impact load. Figures 5–7 show the change curves of the stress tensor components σxx, σyy, and σzz with the volume compression ratio of the three crystals under uniaxial compression. To make a comparison with hydrostatic pressure, the corresponding stress during hydrostatic compression is increased in each figure. In general, as V/V0 decreases, the principal stresses σxx, σyy, and σzz along the [100], [010], and [001] directions increase. By comparison of Figures 5a, 6a, and 7a, the maximum differences of the principal stresses σxx, σyy, and σzz of the ETN along the [100], [010], and [001] directions are 3.2, 2.0, and 3.8 GPa, respectively, when V/V0 is 0.7. By comparison of Figures 5b,6b, and7b, the maximum differences of the principal stresses of NEST-1 along the [100], [010], and [001] directions are 3.1, 4.3, and 3.1 GPa, respectively, when V/V0 is 0.7. By comparison of Figures 5c, 6c, and 7c, the maximum differences between the principal stresses of NG along the [100], [010], and [001] directions are 2.5, 3.4, and 2.9 GPa, respectively, when V/V0 is 0.7. Different variation amplitudes indicate the anisotropic behavior of ETN crystals; NEST-1 and NG crystals have weak anisotropic behavior.

Figure 5.

Stress tensor component σxx and hydrostatic stress of ETN (a), NEST-1 (b), and NG (c) under uniaxial compression.

Figure 7.

Stress tensor component σzz and hydrostatic stress of ETN (a), NEST-1 (b), NG (c) under uniaxial compression.

Figure 6.

Stress tensor component σyy and hydrostatic stress of ETN (a), NEST-1 (b), NG (c) under uniaxial compression.

For ETN, the stress tensor component σzz shows the most obvious change under uniaxial compression. During initial compression (V/V0 > 0.9), σzz increases slowly under uniaxial compression and hydrostatic compression, but the difference is not great. When further compressed, σzz in the [001] direction starts to exceed hydrostatic pressure and σzz in the other two directions. At the end of the compressed state, the σzz value along the [001] direction is 3.8 GPa greater than that along the [010] direction. The change in stress tensor component σyy is not obvious; σyy and hydrostatic pressure along the [100] and [001] directions show almost the same curve. The change trend and amplitude of the stress tensor components σxx and σzz are close, but thare is a difference that the value of σxx along the [100] direction is 3.2 GPa greater than the value of σxx along the [010] direction, which is slightly smaller than the changing value of σzz.

In terms of NEST-1, the stress tensor component σyy shows a significant change under uniaxial compression. When the volume is compressed to 0.2, the σyy value in the [100] direction is greater than the hydrostatic pressure and the σyy value in the other two directions. When V/V0 is 0.7, the σyy value in the [010] direction is 4.3 GPa greater than the value of σyy. However, the change in stress tensor component σzz is not obvious; the σzz along the [100] and [001] directions and hydrostatic pressure show almost the same curve. The change trend and amplitude of the stress tensor components σxx and σyy are approximate. The difference is that the value of σxx along the [100] direction is 3.1 GPa greater than the value of σxx along the [001] direction, which is lower than the value of σyy.

In terms of NG, the stress tensor component σyy shows a large change under uniaxial compression. When the volume is compressed, σyy along the [010] direction and the hydrostatic pressure remain highly consistent, and the σyy values are higher than the σyy values along the [100] and [001] directions. When V/V0 is 0.7, the σyy value in the [010] direction is 3.4 GPa greater than the σyy value in the [100] direction. However, the change in stress tensor component σxx is not obvious; the change trend and amplitude of the stress tensor components σzz and σyy are approximate. The difference is that the value of σzz in the [001] direction is 2.9 GPa greater than the value of σzz in the [010] direction, which slightly less than the change in σyy.

Figure 8 shows the average principal stress of the three crystals under uniaxial compression σ̅ (σ̅ = (σxx + σyy + σzz)/3) and the curve of hydrostatic pressure with volume compression ratio. Obviously, the average principal stress σ̅ and hydrostatic pressure have similar changing trends and amplitudes, suggesting that the anisotropic behavior of the three crystals, ETN, NEST-1, and NG, is weaker than that exhibited from PETN. This may be due to the high symmetry of the crystal and molecule.

Figure 8.

Average principal stress σ̅ and hydrostatic stress of ETN (a), NEST-1 (b), and NG (c) as a function of the compression ratio V/V0 under uniaxial compression.

3.3. Shear Stress

Shear stress is an important driving force for plastic deformation of EM crystals and is the main physical variable to characterize the anisotropism of mechanical machinery, so it is necessary to calculate the maximum shear stress for each uniaxial compression. Under the uniaxial compression, the shear stress is maximum when the angle between crystal and compression reaches 45°, where τxy = (σxx – σyy)/2, τyz = (σyy – σzz)/2, and τxz = (σxx – σzz)/2.

Figure 9 shows the curves of maximum shear stresses τxy, τyz, and τxz of three kinds of crystals along the volume compression ratio V/V0 change. It can be seen from the comparison that the change trends of the maximum shear stress of ETN and NEST-1 are similar, while the change of the maximum shear stress of NG is more complicated. It can be seen from Figure 9a,b that the maximum shear stresses τxy of both ETN and NEST-1 in the [100] and [010] directions increase as V/V0 decreases, which is up to 1.6 GPa; τxy along the [001] direction changes little, always below 0.5 GPa. The other two maximum shear stresses τyz and τxz of ETN and NEST-1 also have similar trends, that is, τyz along the [010] and [001] directions increases as V/V0 decreases, and along the [100] direction, τyz is stably below 0.5 GPa. τxz along the [100] and [001] directions increases as V/V0 decreases, while τxz along the [010] direction is below 0.5 GPa. The difference is that when V/V0 is 0.7, the value of the maximum shear stress τyz (2.0 GPa) in the [100] and [010] directions is higher than the value of τxz (1.5 GPa). By comparison of Figure 9a,d,e, it can be seen that τyz and τxy of ETN in the [010] direction are higher than τxz. Also, τyz and τxy increase exponentially in the [010] direction. It can be observed from Figure 9b,g,h that both τxy and τxz of NEST-1 in the [100] direction are higher than τyz. The maximum shear stress of NG shows no obvious rule in different compression directions, but its value is below 1.5 GPa, which is the smallest of the three kinds of crystals.

Figure 9.

Shear stress maxima τxy (a–c), τxz (d–f), and τyz (g–i) as a function of the compression ratio V/V0 under uniaxial compression.

4. Conclusions

This paper studied the physicochemical properties of typical nitrate energetic materials under hydrostatic and uniaxial compression by combining the ReaxFF/lg field with molecular dynamics simulation. Under hydrostatic compression, the P–V curve and the volume modulus (B0) obtained by fitting the VFRS state equation indicated that the compressibility of the three kinds of crystals is NG > ETN > NEST-1. Due to the different molecular configuration and crystal arrangement, the three kinds of crystals have different change trends in the lattice constants of hydrostatic pressure. The a- and c-axis of ETN can be compressed easily under hydrostatic pressure, while the b-axis cannot be. The b-axis of NEST-1 is the easiest to be compressed, while the a- and c-axis can be compressed slightly when the initial pressure increases. The a-, b-, and c-axes of NG have similar compressibilities. By analyzing the trend of the change of main bond length of the crystal, it can be seen that the N–O bond is the most stable in the three kinds of crystals, and the O–NO2 bond has the largest change. The stability of the C–O bond shows that the NO3 generated by the nitrite ester containing energetic materials is not from the C–O bond breakage.

The average principal stress σ̅ and the hydrostatic pressure of the three kinds of crystals under uniaxial compression have similar trends and amplitudes, indicating that the anisotropic behavior of the three kinds of crystals, ETN, NEST-1, and NG, is weak. The maximum shear stresses τxy and τyz of ETN in the [010] direction are 1.5 GPa higher than τxz. However, the maximum shear stress of NG shows irregularity in different compression directions, implying that there is no obvious correlation between the maximum shear stress and sensitivity. Future work may study the effects of maximum shear stress on crystal sliding systems, which will provide references for understanding the physicochemical properties of energetic materials and the problems of synthesis of energetic materials.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c02829.

Model of ETN, NEST-1, and NG supercell (Figure S1); unit cell parameters and the volume of ETN, NEST-1, and NG crystal under normal temperature and pressure (Table S1) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Strachan A.; Kober E. M.; Van Duin A. C. T.; Oxgaard J.; Goddard W. A. III. Thermal decomposition of RDX from reactive molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 054502 10.1063/1.1831277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riad Manaa M.; Reed E. J.; Fried L. E.; Galli G.; Gygi F. Early chemistry in hot and dense nitromethane: Molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 10146 10.1063/1.1724820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.; Lian P.; Wei D. Q.; Chen X. R.; Zhang Q. M.; Gong Z. Z. Thermal decomposition of the solid phase of nitromethane: Ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 188302 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.188302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue X. G.; Ma Y.; Zeng Q.; Zhang C. Y. Initial decay mechanism of the heated CL-20/HMX cocrystal: A case of the cocrystal mediating the thermal stability of the two pure components. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 4899–4908. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b00698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field J. E. Hot Spot Ignition Mechanisms for Explosives. Acc. Chem. Res. 1992, 25, 489–496. 10.1021/ar00023a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K.; Kalia R. K.; Nakano A.; Vashishta P.; Van Duin A. C. T.; Goddard W. A. III. Dynamic transition in the structure of an energetic crystal during chemical reactions at shock front prior to detonation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 148303 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.148303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J. N.; Wei Y. K.; Zhang X. Q.; Chen X. R.; Ji G. F.; Kotni M. K.; Wei D. Q. Shock response of 1,3,5-trinitroperhydro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX): The C-N bond scission studied by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 122, 135901 10.1063/1.5005804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McEnnis C.; Dikmelik Y.; Spocer J. B. Femtosecond laser-induced fragmentation and cluster formation studies of solid phase trinitrotoluene using time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 254, 557–562. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2007.06.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. C.; Kim K. H.; Yoh J. J. Modeling of high energy laser ignition of energetic materials. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 083536 10.1063/1.2909271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aluker E. D.; Krechetov A. G.; Mitrofanov A. Y.; Zverev A. S.; Kuklja M. M. Understanding limits of the thermal mechanism of laser initiation of energetic materials. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 24482–24486. 10.1021/jp308633y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter J. Bond lengths and angles in pentaerythritol tetranitrate. Acta Crystallogr. 1963, 16, 698. 10.1107/S0365110X6300178X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dick J. J. Effect of crystal orientation on shock initiation sensitivity of pentaerythritol tetranitrate explosive. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1984, 44, 859–861. 10.1063/1.94951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dick J. J.; Mulford R. N.; Spencer W. J.; Pettit D. R.; Garcia E.; Shaw D. C. Shock response of pentaerythritol tetranitrate single crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 1991, 70, 3572–3587. 10.1063/1.349253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dick J. J.; Ritchie J. P. Molecular mechanics modeling of shear and the crystal orientation dependence of the elastic precursor shock strength in pentaerythritol tetranitrate. J. Appl. Phys. 1994, 76, 2726–2737. 10.1063/1.357576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dick J. J. Anomalous shock initiation of detonation in pentaerythritol tetranitrate crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 81, 601–612. 10.1063/1.364201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo C. S.; Holmes C. N.; Souers P. C.; Wu C. J.; Ree F. H.; Dick J. J. Anisotropic shock sensitivity and detonation temperature of pentaerythritol tetranitrate single crystal. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 88, 70–75. 10.1063/1.373626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dick J. J.; Hooks D. E.; Menikoff R.; Martinez A. R. Elastic-plastic wave profiles in cyclotetramethylene tetranitramine crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 96, 374–379. 10.1063/1.1757026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menikoff R.; Dick J. J.; Hooks D. E. Analysis of wave profiles for single-crystal cyclotetramethylene tetranitramine. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 023529 10.1063/1.1828602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badgujar D. M.; Talawar M. B.; Asthana S. N.; Mahulikar P. P. Advances in science and technology of modern energetic materials: An overview. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 151, 289–305. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapötke T. M.; Krumm B.; Llg R.; Troegel D.; Tacke R. The sila-explosives Si(CH2N3)4 and Si(CH2ONO2)4: Silicon analogues of the common explosives pentaerythrityl tetraazide, C(CH2N3)4, and pentaerythritol tetranitrate, C(CH2ONO2)4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 6908–6915. 10.1021/ja071299p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D. Z.; Guo D. Z.; Huang F. L.; An Q. Influence of silicon on the detonation performance of energetic materials from first-principles molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 24481–24487. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b08305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An Q.; Zybin S. V.; Goddard W. A. III.; Jaramillo B. A.; Zhou T. T. Highly shocked polymer bonded explosives at a nonplanar interface: Hot–spot formation leading to detonation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 26551–26561. 10.1021/jp404753v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T. T.; Liu L. C.; Goddard W. A. III.; Zybin S. V.; Huang F. L. ReaxFF reactive molecular dynamics on silicon pentaerythritol tetranitrate crystal validates the mechanism for the colossal sensitivity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 23779–23791. 10.1039/C4CP03781B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. G.; Zybin S. V.; Dasgupta S.; Klapötke T. M.; Goddard W. A. III. Explanation of the colossal detonation sensitivity of silicon pentaerythritol tetranitrate (Si-PETN) explosive. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7490–7491. 10.1021/ja809725p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagoria P. A comparison of the structure, synthesis, and properities of insensitive energetic compounds. Propellants, Explos., Pyrotech. 2016, 41, 452–469. 10.1002/prep.201600032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Politzer P.; Murray J. S. High performance, low sensitivity: conflicting or compatible?. Propellants, Explos., Pyrotech. 2016, 41, 414–425. 10.1002/prep.201500349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamlet M. J.; Adolph H. G. The relationship of impact sensitivity with structure of organic high explosives. II. polynitroaromatic explosives. Propellants, Explos., Pyrotech. 1979, 4, 30–34. 10.1002/prep.19790040204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman S.; Jungová M. Sensitivity and performance of energetic materials. Propellants, Explos., Pyrotech. 2016, 41, 426–451. 10.1002/prep.201500351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manner V. W.; Tappan B. C.; Scott B. L.; Preston D. N.; Brown G. W. Crystal structure, packing analysis, and structural-sensitivity correlations of erythritol tetranitrate. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 6154–6160. 10.1021/cg501362b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez D. E.; Hiskey M. A.; Naud D. L.; Parrish D. Synthesis of an energetic nitrate ester. Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 8431–8433. 10.1002/ange.200803648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espenbetov A. A.; Antipin M. Y.; Struchkov Y. T. Structure of 1,2,3-propanetriol trinitrate (β modification), C3H5N3O9. Acta Crystallogr. C 1984, C40, 2096–2098. 10.1107/S0108270184010775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matyáš R.; Lyčka A.; Jirásko R.; Jakovŷ Z.; Maixner J.; Mišková L.; Künzel M. Analytical Characterization of Erythritol Tetranitrate, an Improvised Explosive. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 759–764. 10.1111/1556-4029.13078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxley J. C.; Smith J. L.; Brady J. E. IV.; Brown A. C. Characterization and analysis of tetranitrate esters. Propellants, Explos., Pyrotech. 2012, 37, 24–39. 10.1002/prep.201100059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matyáš R.; Künzel M.; Růžička A.; Knotek P.; Vodochodshŷ O. Characterization of erythritol tetranitrate physical properties. Propellants, Explos., Pyrotech. 2015, 40, 185–188. 10.1002/prep.201400291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oxley J. C.; Smith J. L.; Brown A. C. Eutectics of erythritol tetranitrate. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 16137–16144. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b04667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman D.; Kosloff R.; Zeiri Y. Effects of nanoscale heterogeneities on the reactivity of shocked erythritol tetranitrate. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 28886–28893. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b11543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oxley J. C.; Furman D.; Brown A. C.; Dubnikova F.; Smith J. L.; Kosloff R.; Zeiri Y. Thermal decomposition of erythritol tetranitrate: A joint experimental and computational study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 16145–16157. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b04668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landerville A. C.; Conroy M. W.; Oleynik I. I.; White C. T. Prediction of isothermal equation of state of an explosive nitrate ester by van der Waals density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 346–348. 10.1021/jz900026j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waring C. E.; Krastins G. The kinetics and mechanism of the thermal decomposition of nitroglycerin. J. Phys. Chem. A 1970, 74, 999–1006. 10.1021/j100700a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Duin A. C. T.; Dasgupta S.; Lorant F.; Goddard W. A. III ReaxFF: A reactive force field for hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 9396–9409. 10.1021/jp004368u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Liu H.; Yang Z.; Li Q.; He Y. Shock-induced hot spot formation and spalling in 1,3,5-trinitroperhydro-1,3,5-triazine containing a cube Void. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 8031–8038. 10.1021/acsomega.9b00589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. P.; Yang Z.; Li Q. K.; He Y. H. Carbon-rich clusters and graphite-like structure formation during early detonation of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene (TNT) via molecular dynamics simulation. Acta Chim. Sin. 2018, 76, 556–563. 10.6023/A18040153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. C.; Liu Y.; Zybin S. V.; Sun H.; Goddard W. A. III. ReaxFF–lg: Correction of the ReaxFF reactive force field for London dispersion, with applications to the equations of state for energetic materials. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 11016–11022. 10.1021/jp201599t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuklja M. M.; Kunz A. B. Ab initio simulation of defects in energetic materials. Part I. Molecular vacancy structure in RDX crystal. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2001, 61, 35–44. 10.1016/S0022-3697(99)00229-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plimpton S. J. Fast parallel algorithms for short–range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995, 117, 1–19. 10.1006/jcph.1995.1039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aktulga H. M.; Fogarty J. C.; Pandit S. A.; Grama A. Y. Parallel reactive molecular dynamics: Numerical methods and algorithmic techniques. Parallel Comput. 2012, 38, 245–259. 10.1016/j.parco.2011.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy M. W.; Oleynik I. I.; Zybin S. V.; White C. T. First-principles investigation of anisotropic constitutive relationships in pentaerythritol tetranitrate. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 094107 10.1103/PhysRevB.77.094107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov I. A.; Fedorova T. P.; Zhuravlev Y. N. Hydrostatic pressure effects on structural and electronic properties of ETN and PETN from first–principles calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 3710–3717. 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b03335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.; Chen C. F. Calculation of bulk modulus for highly anisotropic materials. Phys. Lett. A 2004, 326, 442–448. 10.1016/j.physleta.2004.04.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gan C. K.; Sewell T. D.; Challacombe M. All-electron density-functional studies of hydrostatic compression of pentaerythritol tetranitrate C(CH2ONO2)4. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 769, 035116 10.1103/PhysRevB.69.035116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vinet P.; Smith J. R.; Ferrante J.; Rose J. H. Temperature effects on the universal equation of state of solids. Phys. Rev. B 1987, 35, 1945–1953. 10.1103/PhysRevB.35.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olinger B.; Halleck P. M.; Cady H. H. The isothermal linear and volume compression of pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN) to 10 GPa (100 kbar) and the calculated shock compression. J. Chem. Phys. 1975, 62, 4480–4483. 10.1063/1.430355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landerville A. C.; Conroy M. W.; Budzevich M. M.; Lin Y.; White C. T.; Oleynik I. I. Equations of state for energetic materials from density functional theory with van der Waals, thermal, and zero-point energy corrections. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 251908 10.1063/1.3526754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menikoff R.; Sewell T. D. Fitting forms for isothermal data. High Press. Res. 2001, 21, 121–138. 10.1080/08957950108201010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiskey M. A.; Brower K. R.; Oxley J. C. Thermal decomposition of nitrate esters. J. Phys. Chem. B 1991, 95, 3955–3960. 10.1021/j100163a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.