Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between baseline disease activity and the occurrence of flares after adalimumab tapering or withdrawal in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in sustained remission.

Methods

The PREDICTRA phase IV, randomised, double-blind (DB) study (ImPact of Residual Inflammation Detected via Imaging TEchniques, Drug Levels, and Patient Characteristics on the Outcome of Dose TaperIng of Adalimumab in Clinical Remission Rheumatoid ArThritis (RA) Patients) enrolled patients with RA receiving adalimumab 40 mg every other week who were in sustained remission ≥6 months. After a 4-week, open-label lead-in (OL-LI) period, patients were randomised 5:1 to DB adalimumab taper (every 3 weeks) or withdrawal (placebo) for 36 weeks. The primary endpoint was the association between DB baseline hand and wrist MRI-detected inflammation with flare occurrence.

Results

Of 146 patients treated during the OL-LI period, 122 were randomised to taper (n=102) or withdrawal (n=20) arms. Patients had a mean 12.9 years of active disease and had received adalimumab for a mean of 5.4 years (mean 2.2 years in sustained remission). Overall, 37 (36%) and 9 (45%) patients experienced a flare in the taper and withdrawal arms, respectively (time to flare, 18.0 and 13.3 weeks). None of the DB baseline disease characteristics or adalimumab concentration was associated with flare occurrence after adalimumab tapering. Approximately half of the patients who flared regained clinical remission after 16 weeks of open-label rescue adalimumab. The safety profile was consistent with previous studies.

Conclusions

Approximately one-third of patients who tapered adalimumab versus half who withdrew adalimumab experienced a flare within 36 weeks. Time to flare was numerically longer in the taper versus withdrawal arm. Baseline MRI inflammation was not associated with flare occurrence.

Trial registration number

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, DMARDs (biologic), disease activity, anti-TNF

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Current treatment recommendations suggest that after treatment target has been achieved, tapering of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) may be considered in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who are in stable, long-standing clinical remission.

However, it is still uncertain as to which patients could benefit from tapering with a low risk of flaring.

What does this study add?

The PREDICTRA study (ImPact of Residual Inflammation Detected via Imaging TEchniques, Drug Levels, and Patient Characteristics on the Outcome of Dose TaperIng of Adalimumab in Clinical Remission Rheumatoid ArThritis (RA) Patients) demonstrated that tapering of adalimumab was a viable option for a subset of patients (64%) with established RA who were in deep remission.

Although rescue adalimumab therapy resulted in ≥50% of patients regaining disease control, a considerable proportion of patients (37%–50%) did not regain control despite 16 weeks of rescue adalimumab therapy.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

Tapering bDMARDs is an option for a subset of patients who are in deep, long-standing remission, and in case of a flare, previous bDMARD dose can be reinstituted to help regain remission in some but not all patients.

However, attempts to define this subset based on patient, clinical and imaging characteristics were not successful in this study, suggesting that additional research is needed.

Introduction

The current treat-to-target recommendations for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) suggest starting treatment with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) as soon as possible and adjusting therapy if no improvement is observed by 3 months or if treatment target of sustained remission or low disease activity is not reached by 6 months; addition of a biologic DMARD (bDMARD) is suggested, especially if poor prognostic factors are present.1 2 Rapid implementation of bDMARDs leads to improved outcomes in RA,3 but after sustained clinical remission has been achieved, the question as to whether therapy should be adjusted arises. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) suggest that after treatment target has been achieved, tapering of bDMARDs may be considered in patients who are in stable, long-standing clinical remission.1 2

However, the current evidence regarding bDMARD tapering or discontinuation (complete withdrawal) in patients with RA remains inconclusive. In controlled studies, 13%–81% of patients were able to maintain disease control after tapering or withdrawal of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, with higher percentages of patients failing among those with established RA versus early RA.4–8 Other data on prognostic factors for flare after therapy tapering are limited, and reinstitution of standard TNF inhibitor dosing after a flare has been successful in regaining disease control in some studies,9–11 but not all studies have shown as favourable results.12

Imaging techniques such as MRI and ultrasound allow for accurate identification of subclinical inflammation, even in apparent clinical remission, and this inflammation predicts structural damage progression and may predict relapse in patients who are in clinical remission.11 13–16 MRI has been shown to identify signs of inflammation by synovitis and bone marrow oedema (BME, now known to be osteitis), as well as erosions not otherwise observed with conventional radiographs,17 in a high proportion of patients considered to be in clinical remission.18

The objective of the PREDICTRA study (ImPact of Residual Inflammation Detected via Imaging TEchniques, Drug Levels, and Patient Characteristics on the Outcome of Dose TaperIng of Adalimumab in Clinical Remission Rheumatoid ArThritis (RA) Patients) was to investigate the association between residual baseline disease activity detected by MRI and the occurrence of flares in patients with RA in persistent long-standing clinical remission who were randomised to an adalimumab dose tapering regimen or adalimumab withdrawal, which served as a control arm.

Methods

Participants

PREDICTRA was a phase IV, randomised, double-blind (DB), parallel-group study conducted in 54 sites in Australia, Canada, Europe and the USA (registered per the WHO Trial Registration Data Set at www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu; EudraCT 2014-001114-26).

A detailed description of the study design and patient inclusion criteria has been previously published.19 Briefly, patients with RA who were receiving adalimumab 40 mg every other week (eow) for ≥12 months and who were in stable clinical remission, defined as 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C reactive protein (DAS28(ESR) or DAS28(CRP)) <2.6 for ≥6 months and DAS28(ESR) <2.6 at screening, were eligible to enter this study. Stable concomitant csDMARDs (≥12 weeks), oral corticosteroids (doses <10 mg/day, ≥4 weeks) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs ≥4 weeks) were permitted. Patients not taking methotrexate in a stable dose for ≥12 weeks prior to baseline could be enrolled (up to 20% of overall study population); once a limit of 20% on other csDMARDs or adalimumab monotherapy (no csDMARDs) was met, only patients receiving concomitant methotrexate were allowed in the study. Exclusion criteria included current use of bDMARDs other than adalimumab and any medical condition precluding contrast-enhanced MRI.

Study design and treatments

After a screening period of up to 28 days, patients were enrolled to a 4-week, open-label lead-in (OL-LI) period, during which patients continued to receive adalimumab 40 mg eow and persistent clinical remission was confirmed. Patients with DAS28(ESR) <2.6 who completed the 4-week OL-LI were randomised 5:1 to DB taper arm (adalimumab 40 mg every 3 weeks) and withdrawal control arm (placebo) for 36 weeks. Patients who experienced a flare during the DB period entered an open-label rescue arm (flare week 0) and received open-label adalimumab 40 mg eow for up to 16 weeks (study visits at flare weeks 4, 10 and 16). Flare was defined as either DAS28(ESR) >2.6 and DAS28(ESR) increase >0.6 from DB baseline or DAS28(ESR) increase ≥1.2 from DB baseline, irrespective of absolute DAS28(ESR).

All participants were required to sign a written informed consent statement before the start of any study procedures.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the association between DB baseline (MRI performed between OL-LI period weeks 0 and 4) hand and wrist synovitis, BME, and the composite of both as assessed using the OMERACT Rheumatoid Arthritis Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (RAMRIS) and flare occurrence in patients randomised to the adalimumab taper arm.

Key secondary endpoints have been previously described19 and included time to and proportion of patients with flare or who regained disease control following flare (defined as DAS28(ESR) <2.6 if DAS28(ESR) ≥2.6 at flare or as DAS28(ESR) decrease >1.2 if DAS28(ESR) <2.6 at flare), proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission through week 40, and association between occurrence of flares and DB baseline patient demographics, disease characteristics and adalimumab trough concentrations (taper arm only). In addition, change from DB baseline to week 40 (non-flared patients) or flare week 16 (flared patients) in clinical remission, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI), 28-joint swollen joint count, 28-joint tender joint count, physician-reported and patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, and RAMRIS scores were assessed in the taper and withdrawal arms. Anti-adalimumab antibodies were assessed in the taper and withdrawal arms; a patient was considered to be anti-adalimumab antibody-positive if they had antibody concentration >20 ng/mL and the sample was collected within 30 days after an adalimumab dose.

The occurrence of adverse events (AEs) during the study and up to 70 days after discontinuation of study treatment was also collected.

Statistical analyses

The sample size was based on the precision for estimating the OR for the occurrence of flare with baseline MRI score. Based on an assumed flare rate of 40%, a sample size of 100 patients in the tapering arm ensures a precision for the estimation, with the width of 95% CI no more than 0.19 for an OR of 1.1 and no more than 0.26 for an OR of 1.2. Under a 5:1 randomisation ratio (dose tapering vs withdrawal), 120 patients would be required to be randomised. Accounting for a 10%–20% discontinuation rate during the OL-LI period, approximately 150 patients would be required to be enrolled into the OL-LI period.

The analysis population for the OL-LI period included all patients receiving at least one dose of open-label adalimumab. The primary efficacy analysis population for the DB period included all patients receiving treatment during the DB period.

Logistic regression analyses with occurrence of flare as the dependent variable and MRI scores and other baseline characteristics as independent variables in separate statistical models were conducted. Descriptive statistics including counts and proportions with 95% CI and Kaplan-Meier estimates are provided. Last observation carried forward was used for imputation of missing data. For the DB period, missing values are only imputed up to the time when the patient entered the open-label rescue period.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without any formal patient/patient organisation involvement in study design, development of patient relevant outcomes, interpretation of results, or the writing or editing of the manuscript.

Results

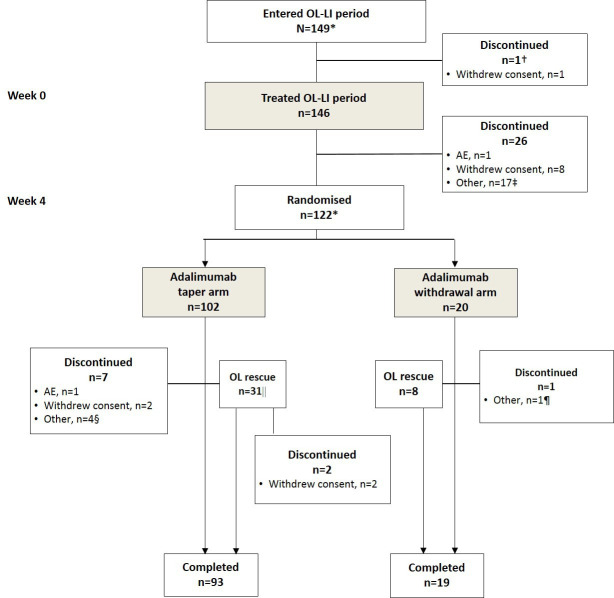

A total of 149 patients entered and 146 were treated with adalimumab in the OL-LI period (figure 1). Of these, 122 were in clinical remission at weeks 0 and 4 and were randomised to the taper (n=102) and withdrawal (n=20) arms. A total of 93 (91%) patients in the taper arm and 19 (95%) patients in the withdrawal arm (including the rescue populations) completed the study. During the DB and rescue periods, the most common reasons for discontinuation of study were withdrawal of consent (n=4), other (n=5) and AEs (n=1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. *Two patients entered the DB period but were not treated during the OL-LI period. During the OL-LI period, five patients were not in remission; of these, two patients did not continue into the DB period, whereas three patients were randomised into the DB period in error (all were due to the baseline DAS28 score being entered incorrectly). †One patient discontinued after withdrawal of consent and was not treated during the OL-LI period. ‡ Other reasons included MRI refusal/not performed/problems, n=8; elevated DAS28/flare, n=4; did not meet randomisation criteria, n=1, protocol violation, n=1, family emergency, n=1; moved, n=1, patient request, n=1. §Other reasons included protocol violation, n=1; patient request after serious AE, n=1; patient unable to attend visits, n=1; final visit mistakenly reported as premature discontinuation, n=1. |1 patient was incorrectly entered and treated in the open-label rescue period. ¶Other reason was patient request. AE, adverse event; DAS28, 28-joint Disease Activity Score; DB, double-blind; OL-LI, open-label, lead-in.

Most patients in the OL-LI treated population were women (75%), with a mean (SD) duration of active disease of 12.9 (10.0) years (n=142). Patients had received adalimumab for a mean (SD) of 5.4 (3.3) years and were in stable clinical remission for a mean (SD) of 2.2 (2.0) years (n=125) (table 1). All patients randomised to the DB period were on concomitant DMARDs at DB baseline, and 44% and 32% of patients had previously received or were receiving NSAIDs and steroids, respectively, at DB baseline.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics at baseline in the OL-LI treated population and at DB baseline in the DB population

| OL-LI treated population (n=146) | DB population | |||

| Taper arm (n=102) | Withdrawal arm (n=20) | Randomised (n=122) | ||

| Women, n (%)* | 109 (75) | 79 (77) | 12 (60) | 91 (75) |

| Race, white, n (%)* | 139 (97), n=143 | 97 (97), n=100 | 20 (100) | 117 (98), n=120 |

| Age, years* | 59.6 (10.3) | 59.2 (10.4) | 62.7 (9.2) | 59.7 (10.3) |

| Prior or concomitant NSAIDs, n (%)† | 65 (45) | 42 (41) | 12 (60) | 54 (44) |

| Prior or concomitant steroids, n (%)† | 46 (32) | 30 (29) | 9 (45) | 39 (32) |

| Concomitant steroids, n (%)† | – | 14 (14) | 4 (20) | 18 (15) |

| Prior or concomitant DMARDs, n (%)† | 146 (100)‡ | 102 (100) | 20 (100) | 122 (100) |

| Methotrexate dose, mg/week§ | 13.6 (5.7), n=122 | 13.6 (5.6), n=85 | 11.7 (5.4), n=18 | 13.3 (5.6), n=103 |

| DAS28(ESR) | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.6) |

| DAS28(ESR) <2.6, n (%) | 141 (97) | 102 (100) | 20 (100) | 122 (100) |

| CDAI ≤2.8, n (%) | 116 (79) | 85 (83) | 19 (95) | 104 (85) |

| SDAI ≤3.3, n (%) | 119 (82) | 89 (87) | 19 (95) | 108 (89) |

| PtGA | 8.7 (11.8) | 6.8 (9.3) | 4.3 (6.7) | 6.4 (8.9) |

| PGA | 3.3 (6.2) | 3.8 (5.1) | 2.6 (4.4) | 3.6 (5.0) |

| PtGA pain | 9.7 (11.0) | 8.9 (11.9) | 6.0 (8.8) | 8.4 (11.5) |

| Synovitis RAMRIS¶ | – | 2.3 (2.2) | 2.1 (1.6), n=19 | 2.3 (2.1), n=121 |

| BME RAMRIS¶ | – | 1.6 (2.8) | 2.1 (2.1) | 1.7 (2.7) |

| Synovitis and BME composite RAMRIS¶ | – | 3.9 (4.1) | 4.3 (3.3), n=19 | 4.0 (4.0), n=121 |

| HAQ-DI | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.5) |

| RAPID-3 | 3.3 (3.0), n=145 | 3.5 (3.3) | 2.0 (2.4) | 3.3 (3.2) |

| SF-36 PCS** | – | 49.8 (7.9), n=99 | 52.1 (6.7) | 50.1 (7.8), n=119 |

| SF-36 MCS** | 54.0 (8.1), n=99 | 56.4 (5.0) | 54.4 (7.7), n=119 | |

| FACIT-fatigue** | 43.8 (6.1), n=100 | 47.6 (3.6) | 44.4 (6.0), n=120 | |

Data are mean (SD) unless otherwise noted.

*At baseline for all populations.

†Prior or concomitant DMARDs, NSAIDs and steroids are taken before or at baseline for the OL-LI population and before or at DB baseline for the DB population. Concomitant steroids include all medications that started prior to the first dose of study drug and continued to be taken after the first dose of study drug.

‡Overall, 145 patients had received prior conventional synthetic DMARDs (including methotrexate, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, gold formulations and/or leflunomide) and 38 patients had received prior biologic DMARDs (excluding adalimumab).

§Methotrexate taken at baseline for the OL-LI population and at DB baseline for the DB population.

¶MRI assessments were done during the OL-LI period and not at the OL-LI baseline.

**Not collected at OL-LI baseline.

BME, bone marrow oedema; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28(ESR), 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate; DB, double-blind; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; FACIT, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; MCS, mental component summary; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OL-LI, open-label lead-in; PCS, physical component summary; PGA, Physician Global Assessment of disease activity; PtGA, Patient Global Assessment of disease activity; RAMRIS, Rheumatoid Arthritis Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score; RAPID-3, Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index; SF-36, Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire.

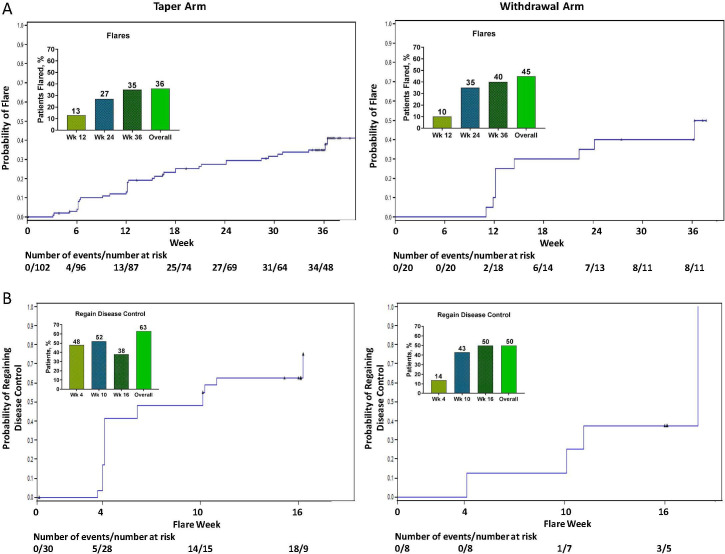

DB population

Overall, a numerically lower percentage of patients in the taper arm (37, 36%) than in the withdrawal arm (9, 45%) experienced a flare by week 40 (figure 2A; inserts). Flare rates were 13%, 27% and 35% in the taper arm and 10%, 35% and 40% in the withdrawal arm at weeks 12, 24 and 36, respectively. Flares occurred later in the taper arm than in the withdrawal arm; using Kaplan-Meier methods, 25% of the patients experienced a flare after 18.0 weeks in the taper arm and 13.3 weeks in the withdrawal arm (first quartile; figure 2A). Due to the low number of flares in the study, the median time to flare was not reached in either arm.

Figure 2.

(A) Percentage of patients who flared and time from DB baseline to flare in the taper and withdrawal arms, and (B) percentage of patients who regained disease control and time from flare to regain of disease control in the taper and withdrawal arms. Last observation carried forward analysis. Flare was defined as either DAS28(ESR) >2.6 and DAS28(ESR) increase >0.6 from DB baseline or DAS28(ESR) increase ≥1.2 from DB baseline, irrespective of absolute DAS28(ESR). Regain of disease control was defined as DAS28(ESR) <2.6 if DAS28(ESR) ≥2.6 at flare and as DAS28(ESR) decrease >1.2 if DAS28(ESR) <2.6 at flare. DAS28(ESR), 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate. DB, double-blind.

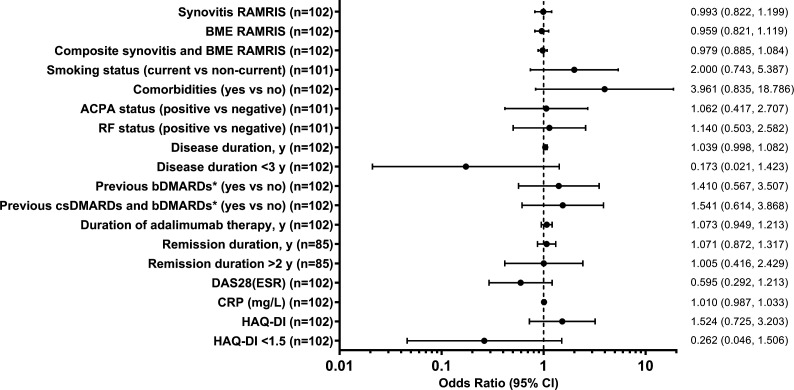

The primary endpoint analysis showed that baseline synovitis RAMRIS, BME RAMRIS, or the synovitis and BME composite RAMRIS were not associated with flare occurrence in the taper arm (figure 3). Similarly, none of the other assessed DB baseline patient characteristics or demographics was associated with a flare.

Figure 3.

DB baseline parameters and occurrence of flare among patients in the taper arm. *Excluding adalimumab. ACPA, anticitrullinated peptide antibody; bDMARDs, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; BME, bone marrow oedema; CRP, C reactive protein; csDMARDs, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; DAS28(ESR), 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate; DB, double-blind; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; RAMRIS, Rheumatoid Arthritis MRI Score; RF, rheumatoid factor.

Clinical remission defined as DAS28(ESR) <2.6 was maintained by 86% (64 of 74) of patients in the taper arm and 85% (11 of 13) in the withdrawal arm who were still in the DB period at week 40 (table 2). As expected, patients who did not experience a flare during the study generally maintained or improved most secondary efficacy endpoints and PROs at week 40 in both the taper and withdrawal arms, suggesting long-term deep remission (online supplementary table S1). Overall, 76% (48 of 63) of patients in the taper arm and 82% (9 of 11) of patients in the withdrawal arm had normal HAQ-DI at week 40.

Table 2.

Percentage of patients who maintained clinical remission at week 40 in DB treated patients who were still in the DB period at week 40

| Taper arm (n=102) | Withdrawal arm (n=20) | |

| DAS28(ESR) <2.6 | 64/74 (86.5) | 11/13 (84.6) |

| SDAI ≤3.3 | 57/74 (77.0) | 12/13 (92.3) |

| CDAI ≤2.8 | 56/74 (75.7) | 12/13 (92.3) |

LOCF analysis.

CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28(ESR), 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate; DB, double-blind; LOCF, last observation carried forward; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index.

annrheumdis-2020-217246supp001.pdf (36.2KB, pdf)

Rescue population

Overall, 39 patients entered the rescue period (31 of 102 (30%) in the taper arm and 8 of 20 (40%) in the withdrawal arm). Among patients who flared, 38% (11 of 29) of patients in the taper arm and 50% (4 of 8) of patients in withdrawal arm regained disease control after 16 weeks of open-label adalimumab rescue therapy (figure 2B; inserts). Time to regain disease control (first quartile based on Kaplan-Meier methods) was 4.1 weeks in the taper arm and 10.6 weeks in the withdrawal arm (figure 2B). Approximately half of the patients who flared (13 of 29 in the taper arm and 4 of 8 in the withdrawal arm) were in clinical remission, defined as DAS28(ESR) <2.6, Simplified Disease Activity Index ≤3.3 and Clinical Disease Activity Index ≤2.8, at flare week 16.

As expected, most clinical activity and PRO measures worsened from DB baseline to flare week 0, including individual DAS28(ESR) components (online supplementary table S2), and generally remained worsened at flare week 16 in both the taper and withdrawal arms despite rescue therapy (online supplementary table S1). Overall, 52% (15 of 29) of patients in the taper arm and 71% (5 of 7) of patients in the withdrawal arm had normal HAQ-DI score at flare week 16.

Other secondary endpoints

No associations between adalimumab concentrations at DB baseline and the occurrence of flare by week 40 were observed in the taper arm (mean (SD) adalimumab, 7.8 (4.9) μg/mL in the 37 flared patients vs 8.0 (4.6) μg/mL in the 64 non-flared patients) or in the withdrawal arm (mean (SD) adalimumab, 8.8 (3.9) μg/mL in the 9 flared patients vs 7.7 (4.9) μg/mL in the 11 non-flared patients).

Anti-adalimumab antibodies were detected in 3.3% of patients overall; 2.9% (3 of 102) of patients in the taper arm and 5.0% (1 of 20) in the withdrawal arm were positive for anti-adalimumab antibodies.

Safety

During the OL-LI period, 25% of patients experienced AEs and 3% experienced serious AEs (table 3). Similar proportion of patients experienced AEs during the DB period in the taper (61%), withdrawal (60%) and rescue (62%) arms; a greater percentage of patients in the rescue arm experienced serious AEs (8%) than in the taper (1%) or withdrawal (0%) arms. Most serious AEs were considered not to be related to treatment and included four events in the OL-LI period (pneumonia, atrial fibrillation, comminuted fracture and transient ischaemic attack), one event in the taper arm (breast cancer, possibly related to study drug) and three events in the rescue arm (pleural effusion (possibly related to study drug), retinal vein occlusion and osteoarthritis). No opportunistic infections, tuberculosis, non-melanoma skin cancer, lymphoma, demyelinating disorders or deaths were observed during the study (table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence of AEs during OL-LI period and DB randomised period

| AE, n (%) | OL-LI treated population (n=146) |

DB population | Rescue population (n=39) | |

| Taper arm (n=102) | Withdrawal arm (n=20) | |||

| Any AE | 36 (25) | 62 (61) | 12 (60) | 24 (62) |

| Serious AE* | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 3 (8) |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation† | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Any AE related to study drug | 11 (8) | 26 (25) | 5 (25) | 9 (23) |

| Any serious AE related to study drug* | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Infection | 11 (8) | 34 (33) | 8 (40) | 15 (38) |

| Serious infection | 1 (1)‡ | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Opportunistic infections§ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tuberculosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignancy¶ | 0 | 1 (1)** | 0 | 0 |

| NMSC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Demyelinating disorder | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In the OL-LI population, a treatment-emergent AE was defined as any AE with an onset date on or after the first dose of study drug and before the first DB dose or up to 70 days after the last dose if the patient discontinued prematurely.

In the DB population, a treatment-emergent AE was defined as any AE with an onset date on or after the first DB dose and before the open-label rescue period or up to 70 days after the last dose of study drug if the patient discontinued prematurely from the DB period.

In the rescue population, a treatment-emergent AE was defined as any AE with an onset date on or after the first dose of open-label rescue adalimumab and up to 70 days after the last dose of study drug.

*Serious AEs (and serious AEs possibly related to study drug as assessed by the investigator) included atrial fibrillation, pneumonia, comminuted fracture and transient ischaemic attack (OL-LI treated population), breast cancer (possibly related) (DB taper arm), and retinal vein occlusion, osteoarthritis and pleural effusion (possibly related) (rescue population).

†AEs leading to discontinuation included herpes zoster (OL-LI treated population) and breast cancer and cough (DB taper arm).

‡Pneumonia.

§Excluding oral candidiasis and tuberculosis.

¶Other than lymphoma, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, leukaemia, NMSC or melanoma.

**Breast cancer.

AE, adverse event; DB, double-blind; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; OL-LI, open-label lead-in.

Discussion

The PREDICTRA study demonstrated that baseline MRI measures of inflammation were not associated with flare occurrence after tapering of adalimumab. The enrolled patients were selected for sustained clinical remission in the OL-LI period (unlike previous studies where history of remission or single time-point remission was the inclusion criteria) and had low inflammation on MRI at baseline, and this homogeneity in low scores may have limited the ability of this study to demonstrate a relationship between objectively assessed MRI inflammation and flare. This is in contrast to previous studies that demonstrated synovitis was associated with bDMARD tapering failure.11 15 16 However, all these studies were smaller (≤77 patients) and usually in patients with earlier disease.

The PREDICTRA study also assessed whether tapering or withdrawal of adalimumab therapy is feasible in patients with established RA who were in persistent, long-standing remission. A control (withdrawal) arm was included as a study design element to ensure the objectivity of flare assessments in the primary study arm. Our findings demonstrated that approximately one-third of patients who tapered adalimumab to every 3 weeks compared with half who completely withdrew adalimumab therapy experienced a flare within 36 weeks. Time to flare was shorter in the withdrawal arm versus the taper arm. After a flare, ≥50% of patients regained disease control with up to 16 weeks of adalimumab rescue therapy; however, a considerable proportion of patients (37% in the taper arm and 50% in the withdrawal arm) did not. These results suggest that tapering of bDMARDs is only a viable option for a subset of patients. Attempts to define this subset of patients based on baseline clinical and imaging characteristics associated with the occurrence of flare were not successful in this study.

As expected, the enrolled patients in sustained clinical remission on adalimumab 40 mg eow had low clinical disease activity and low inflammation on MRI at baseline. These endpoints were maintained or improved from DB baseline to week 40 in both the taper and withdrawal arms, suggesting deep remission and demonstrating that, although the flare criteria were based on disease activity, the lack of flare was also associated with maintenance of other endpoints. In contrast, among patients who flared, most of these endpoints worsened from DB baseline to flare week 16, regardless of adalimumab rescue therapy in both arms. These findings further support the notion that not all patients do well after bDMARD tapering or withdrawal, or regain disease control if reinitiation of therapy is required, especially with long-standing disease.

Our results align with the current EULAR and ACR treatment guidelines that suggest tapering of bDMARDs may be considered in patients who are in stable, long-standing clinical remission.1 2 However, a reported 21%–100% of patients experience a relapse within 12 months of dose reduction.20 Furthermore, significantly more short-lived flares (73% vs 27% of patients) and radiographic progression at 18 months were observed with dose tapering versus dose continuation in an open-label, randomised RA study of TNF inhibitors.21 Because many patients express a desire to taper therapy or take a ‘drug holiday’ when in remission,22 it is essential to identify those who are candidates for therapy tapering. In general, patients with early RA or those with deeper or longer clinical remission are less likely to experience disease flare after bDMARD tapering.23 The latter is supported by the PREDICTRA data, as 64% of patients with established RA (mean disease duration of 12.9 years) who were in deep, long remission (mean DAS28(ESR) of 1.7) for a mean of 5.4 years did not experience a flare after bDMARD tapering. Although no variable was associated with flare occurrence in our study, baseline DAS28(ESR) was a predictor of remission (DAS28(ESR) <2.6) after withdrawal of adalimumab therapy in the observational Humira discontinuation without functionaland radiographic damage progressioN follOwing sustained Remission (HONOR) study. The study also identified DAS28(ESR) ≤2.16 as a critical cut-off point for predicting flare; 78% of patients with mean DAS28(ESR) ≤2.16 at the time of adalimumab withdrawal maintained remission after 6 months (vs 2% for DAS28(ESR) >2.16, <2.6).24 However, mean disease duration (6.6 vs 12.9 years), adalimumab treatment duration (1.2 vs 5.4 years) and methotrexate dose (8.1 vs 13.3 mg/week) were lower in HONOR study patients than in patients in the PREDICTRA study.

The mean serum adalimumab concentrations at DB baseline were similar in patients who flared and did not flare in both arms, demonstrating no association between adalimumab concentration and the occurrence of flare by week 40. Neither adalimumab serum concentrations nor baseline antibody status was predictive of flare after tapering or withdrawal. Overall, the incidence of AEs and serious AEs was low, and the adalimumab safety profile was consistent with that reported previously.25

The strengths of this randomised, placebo-controlled DB study included that it only enrolled patients with established RA (mean 12.9 years of active disease) who were in long-standing remission with adalimumab therapy and addressed a clinical question relevant for the field. Other strengths included inclusion of a withdrawal arm that served as a control and established differences between tapering and completely withdrawing therapy, as well as an open-label rescue arm that provided an opportunity to assess the effectiveness of retreatment with adalimumab. Limitations of the study include a restricted and relatively small patient population (<150 patients with established RA in long-term remission), limited trial duration and time to assess disease control after 16 weeks. Furthermore, the baseline inflammation was low, which limited the ability to test the performance of MRI in this population of patients in deep, long-term remission.

Acknowledgments

AbbVie and the authors thank the patients, study sites and investigators who participated in this clinical trial. AbbVie Inc. was the study sponsor and contributed to study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing, reviewing and approval of the final version of the manuscript. Maja Hojnik, MD, PhD, a former employee of AbbVie, provided study support. Statistical support was provided by Xiaolei Leahy and Kristina Unnebrink, PhD, of AbbVie. Medical writing support, including drafting of the manuscript, was provided by Maria Hovenden, PhD, of Complete Publication Solutions, LLC (North Wales, Pennsylvania), a CHC Group company, and was funded by AbbVie. PE and PGC are supported in part by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leeds Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Presented at: Part of this work was previously presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology, 12–15 June 2019, Madrid, Spain (Emery et al, Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2019;78:1132–1133).

Contributors: Study concept and design: PE, GRB, EN, LS, PGC. Acquisition of data: PE, GRB, EN, LS, PGC. Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: FK. All authors had access to the data, commented on the report drafts and approved the final submitted version.

Funding: This study was funded by AbbVie.

Competing interests: PE has received research grants and/or consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz and UCB. GRB has received research grants and/or consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz and UCB. EN has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, UCB, Lilly, Novartis, Janssen and Celgene GmbH, and consulting fees from AbbVie. LS has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Roche. IL and FK are full-time employees of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock or stock options. PGC has received speakers' bureau or consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer and Roche.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, the ethical principles of Good Clinical Practice, local laws and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymised, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols and clinical study reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

References

- 1. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, et al. . 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1–26. 10.1002/art.39480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. . EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960–77. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rein P, Mueller RB. Treatment with biologicals in rheumatoid arthritis: an overview. Rheumatol Ther 2017;4:247–61. 10.1007/s40744-017-0073-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smolen JS, Emery P, Fleischmann R, et al. . Adjustment of therapy in rheumatoid arthritis on the basis of achievement of stable low disease activity with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone: the randomised controlled OPTIMA trial. Lancet 2014;383:321–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61751-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Vollenhoven RF, Østergaard M, Leirisalo-Repo M, et al. . Full dose, reduced dose or discontinuation of etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:52–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fautrel B, Pham T, Alfaiate T, et al. . Step-down strategy of spacing TNF-blocker injections for established rheumatoid arthritis in remission: results of the multicentre non-inferiority randomised open-label controlled trial (STRASS: Spacing of TNF-blocker injections in Rheumatoid ArthritiS Study). Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:59–67. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smolen JS, Nash P, Durez P, et al. . Maintenance, reduction, or withdrawal of etanercept after treatment with etanercept and methotrexate in patients with moderate rheumatoid arthritis (PRESERVE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:918–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61811-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Emery P, Hammoudeh M, FitzGerald O, et al. . Sustained remission with etanercept tapering in early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1781–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1316133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smolen JS, Emery P, Ferraccioli GF, et al. . Certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis patients with low to moderate activity: the CERTAIN double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:843–50. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Mimori T, et al. . Discontinuation of infliximab after attaining low disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: RRR (remission induction by Remicade in RA) study. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1286–91. 10.1136/ard.2009.121491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alivernini S, Peluso G, Fedele AL, et al. . Tapering and discontinuation of TNF-α blockers without disease relapse using ultrasonography as a tool to identify patients with rheumatoid arthritis in clinical and histological remission. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:39. 10.1186/s13075-016-0927-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rakieh C, Saleem B, Takase K, et al. . THU0136 Long term outcomes of stopping tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFI) in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who are in sustained remission: is it worth the risk? Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:A208.3–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.664 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown AK, Conaghan PG, Karim Z, et al. . An explanation for the apparent dissociation between clinical remission and continued structural deterioration in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2958–67. 10.1002/art.23945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hetland ML, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Junker P, et al. . Radiographic progression and remission rates in early rheumatoid arthritis - MRI bone oedema and anti-CCP predicted radiographic progression in the 5-year extension of the double-blind randomised CIMESTRA trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1789–95. 10.1136/ard.2009.125534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Naredo E, Valor L, De la Torre I, et al. . Predictive value of Doppler ultrasound-detected synovitis in relation to failed tapering of biologic therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2015;54:1408–14. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iwamoto T, Ikeda K, Hosokawa J, et al. . Prediction of relapse after discontinuation of biologic agents by ultrasonographic assessment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in clinical remission: high predictive values of total gray-scale and power Doppler scores that represent residual synovial inflammation before discontinuation. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1576–81. 10.1002/acr.22303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American College of Rheumatology Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials Task Force Imaging Group and Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Magnetic Resonance Imaging Inflammatory Arthritis Working Group Review: the utility of magnetic resonance imaging for assessing structural damage in randomized controlled trials in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2513–23. 10.1002/art.38083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gandjbakhch F, Haavardsholm EA, Conaghan PG, et al. . Determining a magnetic resonance imaging inflammatory activity acceptable state without subsequent radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis: results from a followup MRI study of 254 patients in clinical remission or low disease activity. J Rheumatol 2014;41:398–406. 10.3899/jrheum.131088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Emery P, Burmester GR, Naredo E, et al. . Design of a phase IV randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the ImPact of Residual Inflammation Detected via Imaging TEchniques, Drug Levels and Patient Characteristics on the Outcome of Dose TaperIng of Adalimumab in Clinical Remission Rheumatoid ArThritis (RA) patients (PREDICTRA).. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019007. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fautrel B, Den Broeder AA. De-intensifying treatment in established rheumatoid arthritis (RA): why, how, when and in whom can DMARDs be tapered? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015;29:550–65. 10.1016/j.berh.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Herwaarden N, van der Maas A, Minten MJM, et al. . Disease activity guided dose reduction and withdrawal of adalimumab or etanercept compared with usual care in rheumatoid arthritis: open label, randomised controlled, non-inferiority trial. BMJ 2015;350:h1389. 10.1136/bmj.h1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Markusse IM, Akdemir G, Huizinga TWJ, et al. . Drug-free holiday in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study to explore patients' opinion. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:1155–9. 10.1007/s10067-014-2500-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schett G, Emery P, Tanaka Y, et al. . Tapering biologic and conventional DMARD therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: current evidence and future directions. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1428–37. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hirata S, Saito K, Kubo S, et al. . Discontinuation of adalimumab after attaining disease activity score 28-erythrocyte sedimentation rate remission in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (HONOR study): an observational study. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:R135. 10.1186/ar4315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, et al. . Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn's disease. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:517–24. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2020-217246supp001.pdf (36.2KB, pdf)