Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to identify accurate prognostic factors for postoperative papillary thyroid adenocarcinoma (PTAC) using a competing-risks model based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Material/Methods

Data on patients with PTAC who had received surgery between 2010 and 2015 in the SEER database were extracted. A univariate analysis was performed while considering competing risks using the cumulative incidence function, with Nelson-Aalen cumulative risk curves of the incidence function for PTAC-specific death were calculated and then compared between 2 groups using Gray’s test. To identify the factors that affect the cumulative incidence of PTAC-specific death, a multivariate analysis using the Fine-Gray model was performed.

Results

The 8324 eligible surgical PTAC patients included 101 patients who died from PTAC and 129 patients who died from other causes. The univariate Gray’s test revealed that the cumulative incidence rate for events of interest was significantly affected (P<0.05) by age, sex, marital status, metastasis, differentiation grade, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, radiation status, chemotherapy status, regional lymph nodes removal, and tumor size. Multivariate competing-risks analyses showed that age, sex, metastasis, differentiation grade, radiation status, chemotherapy status, and tumor size were independent risk factors for the postoperative prognosis of PTAC patients (P<0.05). The results of multivariate Cox regression were different, with marital status also appearing as an independent risk factor.

Conclusions

This study established a competing-risks analysis model to evaluate the risk factors of surgical PTAC patients. Our findings may be useful for improving patient prognoses and decision-making when providing individualized treatments.

MeSH Keywords: Prognosis, Survival Rate, Thyroid Neoplasms

Background

Thyroid nodules cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy [1], constituting 2–3% of all new cancers diagnosed each year in the USA, and its incidence worldwide has been steadily increasing for more than 30 years [2]. Thyroid cancer is most frequently diagnosed in females aged 45–55 years, and the risk factors include a personal history of head and neck radiation exposure and a family history of thyroid cancer [3]. Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) accounts for approximately 80% of all thyroid cancer cases [4]. The mainstay of treatment for PTC includes surgery, with postoperative adjuvant radioactive iodine therapy also being applied to some patients. Although the overall prognosis of PTC is usually excellent, there are aggressive subtypes that can cause significant morbidity and even lead to mortality [5], which indicates the need for an accurate knowledge of the prognostic risk factors.

There have been many investigations of the prognostic factors for PTC [6–8], but almost all of them have used traditional survival-analysis methods when analyzing multiple potential factors, such as the Kaplan-Meier marginal regression analysis of patient survival probability, the log-rank test for comparing survival curves, or the Cox proportional-hazards model. The premise of regression in traditional survival analysis is to assume that the censoring time is independent of the expiration time, which assumes that there is no competing risk present and that the outcome is a single endpoint [9]. However, clinical survival data are often associated with multiple outcomes, which may have a competing relationship. The traditional incidence analysis methods often treat such competing events by censoring, which may overestimate the cumulative incidence [10,11]. These aspects indicate that the competing-risks model should be needed to handle multiple endpoints.

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) collects cancer incidence data from population-based cancer registries covering approximately 34.6% of the USA population [12]. The aim of the present study was to identify accurate prognostic factors for papillary thyroid adenocarcinoma (PTAC) receiving surgery using a competing-risks model based on data from the SEER database. We also compared the performance of this model with that of a Cox proportional-hazards model in predicting prognostic factors for PTAC.

Material and Methods

Database

Data on patients with PTAC receiving surgery were extracted using the SEER*Stat software (version 8.3.6). The SEER data set was initiated in 1973 as the main USA population-based cancer registry. This database contains data from many geographic regions and covers information on demographics, staging, treatments, and survival; however, certain specific clinical details are not available [13].

Data collection and analysis

We searched the SEER database for all cases of PTAC registered between 2010 and 2015 using the tumor-site ICD-9 code C73.9 (“Thyroid gland”) and the ICD-O-3 “Hist/behave” code 8260/3 (“Papillary adenocarcinoma, NOS”). Another inclusion criterion was surgery being performed. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) only autopsy findings being available, 2) not the first malignant primary indicator, and 3) incomplete information on survival time. For all of the included patients, the following information was extracted: sex, age at diagnosis, grade, summary stage (localized, regional, or distant), American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, radiation status, chemotherapy status, regional lymph nodes removal, cause of death, vital status, race, insurance status, marital status, tumor size, and survival time.

The seventh edition of the AJCC staging system was adopted. The final analysis was applied to 8324 eligible surgical PTAC patients. Since the individual patient data in the SEER database are de-identified, it was not necessary to obtain approval from an ethics committee or an institutional review board.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Continuous data are showed as mean±standard deviation values. In order to facilitate the analysis of the competing-risks model according to the SEER cause-specific death classification and vital-status recode in the SEER database, all patient follow-up outcomes were divided into the following 3 categories: PTAC-specific death, competing events, and censored events. The cumulative incidence function (CIF) represents the probability of the K-th event before time t and other events: CIFk(t)=Pr(T≤t, D=k) [14]. The CIF was used as univariate analysis to calculate the probability of each event, and Nelson-Aalen cumulative risk curves of the incidence function for PTAC-specific death were calculated and then compared between 2 groups using Gray’s test. The Fine-Gray model was performed as multivariate analysis to identify the factors that affect the cumulative incidence of PTAC. The Fine-Gray model is suitable for predicting personal risks, estimating the risk and prognosis of disease, and establishing clinical prediction model. This model can be adapted to analyze the cumulative incidence of focus events [15]. We also analyzed a Cox regression model and compared its results with those of the Fine-Gray model. Finally, multivariate analysis was repeated using age as a covariate over time based on the Bayesian information criterion.

All of data analyses performed in this study were implemented using SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute), IBM SPSS software (version 24.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), and the R package. Probability values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant, and all tests were bilateral.

Results

Patient characteristics

Table 1 presents the basic information of the patients. The 8324 eligible surgical PTAC patients were aged 46.16±15.10 years. Most of them were female (n=6240, 74.96%), married (n=5335, 64.09%), white (n=6620, 79.53%), and insured (n=7963, 95.66%), and had a well-differentiated grade (n=6776, 81.40%), had localized or regional metastasis (7995, 96.05%), were at AJCC stage I (n=6142, 73.79%), had a tumor size of <20 mm (n=5687, 68.32%), had either not received chemotherapy or had an unknown chemotherapy status (n=8186, 98.34%), and had their regional lymph nodes removed (n=5251, 63.08%). There were 129 patients who died from other causes, accounting for 1.55% of all of the included patients, while 101 patients died from PTAC (1.21%). The patients who had died from PTAC or other causes tended to be older. The patients who died from PTAC were more likely to be male, separated/divorced/widowed, and American Indian or Native Alaskan, and had distant metastasis, undifferentiated grade, and AJCC stage IV, had received chemotherapy, and had a tumor size of >40 mm.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics and demographics.

| Variables | All (n=8234) | Death to thyroid papillary adenocarcinoma (n=101) | Death to other reasons (n=129) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 46.155±15.101 | 65.436±14.278 | 64.682±14.988 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1994 | 44 (2.207%) | 56 (2.808%) |

| Female | 6240 | 57 (0.913%) | 73 (1.170%) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 5335 | 59 (1.106%) | 77 (1.443%) |

| Unmarried | 2067 | 14 (0.677%) | 23 (1.113%) |

| DSW | 832 | 28 (3.365%) | 29 (3.486%) |

| Race | |||

| White | 6620 | 87 (1.314%) | 103 (1.556%) |

| Black | 432 | 3 (0.6945) | 10 (2.315%) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1149 | 10 (0.87%) | 14 (1.218%) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 33 | 1 (3.030%) | 2 (6.061%) |

| Stage | |||

| Localized | 4809 | 9 (0.187%) | 72 (1.497%) |

| Regional | 3186 | 44 (1.381%) | 42 (1.318%) |

| Distant | 239 | 48 (20.084%) | 15 (6.276%) |

| Grade | |||

| 6Well differentiated | 6776 | 33 (0.487%) | 104 (1.535%) |

| Moderately differentiated | 1220 | 12 (0.984%) | 18 (1.475%) |

| Poorly differentiated | 188 | 26 (13.830%) | 5 (2.660%) |

| Undifferentiated | 70 | 30 (42.857%) | 2 (2.857%) |

| AJCC | |||

| I | 6142 | 10 (0.163%) | 62 (1.009%) |

| II | 356 | 3 (0.843%) | 12 (3.371%) |

| III | 1052 | 8 (0.760%) | 27 (2.567%) |

| IV | 684 | 80 (11.696%) | 28 (4.094%) |

| Radiation | |||

| Yes | 4230 | 68 (1.608%) | 56 (1.324%) |

| No/unknown | 4004 | 33 (0.824%) | 73 (1.8235) |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Yes | 48 | 25 (52.083) | 1 (2.083%) |

| No/unknown | 8186 | 76 (0.928%) | 128 (1.564%) |

| Insurance | |||

| Insured | 7963 | 99 (1.243%) | 125 (1.570%) |

| Uninsured/unknown | 271 | 2 (0.738%) | 4 (1.476%) |

| Regional lymph nodes removal | |||

| Yes | 5251 | 80 (1.524%) | 80 (1.524%) |

| No | 2983 | 21 (0.704%) | 49 (1.643%) |

| Tumor size | |||

| 1–10 mm | 3020 | 6 (0.199%) | 35 (1.159%) |

| 11–20 mm | 2667 | 15 (0.562%) | 35 (1.312%) |

| 21–40 mm | 1887 | 34 (1.802%) | 33 (1.749%) |

| >40 mm | 660 | 46 (6.970%) | 26 (3.939%) |

DSW – divorced, separated or widowed.

Univariate analysis of the prognosis of PTAC

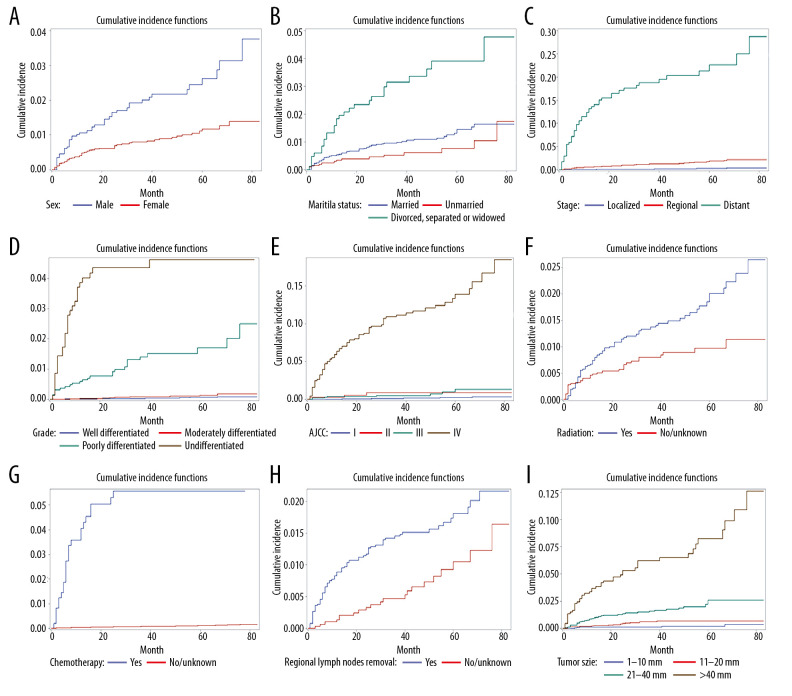

A univariate analysis using Gray’s test applied to 12 potential prognostic factors showed that age, sex, marital status, metastasis, differentiation grade, AJCC stage, radiation status, chemotherapy status, regional lymph nodes removal, and tumor size significantly affected the prognosis of the PTAC patients. The Nelson-Aalen cumulative risk curves for variables in multiple categories are shown in Figure 1. For most variables, the CIF increased over 1, 3, and 6 years, and was higher for distant metastasis, undifferentiated grade, receiving chemotherapy, larger tumors, and AJCC stage IV. The CIF values among the patients with the undifferentiated grade were 38.6%, 43.5%, and 46.1% at 1, 3, and 6 years, respectively. The results from the univariate analysis and CIF values are listed in detail in Table 2.

Figure 1.

(A) Cumulative incidence curves of cause-specific death according to sex. (B) Cumulative incidence curves of cause-specific death according to marital status. (C) Cumulative incidence curves of cause-specific death according to stage. (D) Cumulative incidence curves of cause-specific death according to grade. (E) Cumulative incidence curves of cause-specific death according to American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). (F) Cumulative incidence curves of cause-specific death according to radiation. (G) Cumulative incidence curves of cause-specific death according to chemotherapy. (H) Cumulative incidence curves of cause-specific death according to regional lymph nodes removal. (I) Cumulative incidence curves of cause-specific death according to tumor size.

Table 2.

Univariable competing risk analysis in patients with thyroid papillary adenocarcinoma.

| Variables | Gray’s test | p-Value | Cumulative incidence function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-months | 36-months | 72-months | |||

| Age | 626.943 | <0.0001 | |||

| Sex | 20.333 | <0.0001 | |||

| Male | 0.011 | 0.02 | 0.031 | ||

| Female | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.013 | ||

| Marital status | 35.963 | <0.0001 | |||

| Married | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.016 | ||

| Unmarried | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.011 | ||

| DSW | 0.018 | 0.031 | 0.048 | ||

| Race | 3.387 | 0.336 | |||

| White | 0.006 | 0.012 | 0.019 | ||

| Black | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.017 | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.081 | ||

| Stage | 733.162 | <0.0001 | |||

| Localized | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.004 | ||

| Regional | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.022 | ||

| Distant | 0.132 | 0.188 | 0.250 | ||

| Grade | 1319.580 | <0.0001 | |||

| Well differentiated | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.009 | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.019 | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 0.059 | 0.141 | 0.201 | ||

| Undifferentiated | 0.386 | 0.435 | 0.461 | ||

| AJCC | 685.372 | <0.0001 | |||

| I | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.003 | ||

| II | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.009 | ||

| III | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.013 | ||

| IV | 0.064 | 0.112 | 0.167 | ||

| Radiation | 8.937 | 0.003 | |||

| Yes | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.024 | ||

| No/unknown | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.011 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 1009.614 | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 0.406 | 0.557 | 0.557 | ||

| No/unknown | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.015 | ||

| Insurance | 0.450 | 0.503 | |||

| Insured | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.019 | ||

| Uninsured/unknown | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.009 | ||

| Regional lymph nodes removal | 10.382 | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 0.009 | 0.014 | 0.022 | ||

| No | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.012 | ||

| Tumor size | 224.703 | <0.0001 | |||

| 1–10 mm | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 | ||

| 11–20 mm | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.007 | ||

| 21–40 mm | 0.009 | 0.016 | 0.026 | ||

| >40 mm | 0.037 | 0.062 | 0.109 | ||

DSW – divorced, separated or widowed.

Results from the multivariate analysis

The factors that were statistically significant (P<0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in the Fine-Gray model. The results showed that age, sex, metastasis, differentiation grade, radiation status, chemotherapy status, and tumor size were independent risk factors for the prognosis of the PTAC patients.

The results of the univariate Cox regression analysis were similar to those of the univariate analysis performed using Gray’s test. The factors that were statistically significant in the univariate Cox regression analysis (P<0.05) were included in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. The results showed that marital status was an independent risk factor in addition to age, sex, metastasis, differentiation grade, radiation status, chemotherapy status, and tumor size. The results obtained in the multivariate analyses of the Fine-Gray model and using Cox regression are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis in patients with thyroid papillary adenocarcinoma.

| Variables | Fine-Gray regression analysis | COX regression analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | |

| Age | <0.0001 | 1.052 | 1.031–1.073 | <0.0001 | 1.059 | 1.039–1.078 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Female | 0.008 | 0.547 | 0.351–0.855 | 0.007 | 0.554 | 0.362–0.849 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Unmarried | 0.734 | 1.114 | 0.597–2.078 | 0.605 | 1.173 | 0.640–2.150 |

| DSW | 0.093 | 1.631 | 0.922–2.884 | 0.044 | 1.709 | 1.016–2.877 |

| Stage | ||||||

| Localized | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Regional | 0.005 | 5.671 | 1.670–19.260 | 0.001 | 6.032 | 2.065–17.619 |

| Distant | 0.0004 | 10.217 | 2.822–36.982 | <0.0001 | 11.762 | 3.909–35.390 |

| Grade | ||||||

| Well differentiated | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Moderately differentiated | 0.685 | 1.153 | 0.579–2.298 | 0.693 | 1.145 | 0.584–2.246 |

| Poorly differentiated | <0.0001 | 5.508 | 2.709–11.200 | <0.0001 | 5.419 | 2.947–9.963 |

| Undifferentiated | <0.0001 | 7.247 | 3.209–16.367 | <0.0001 | 8.258 | 4.150–16.434 |

| AJCC | ||||||

| I | Reference | Reference | ||||

| II | 0.366 | 2.185 | 0.402–11.878 | 0.336 | 2.051 | 0.474–8.865 |

| III | 0.384 | 0.598 | 0.188–1.900 | 0.247 | 0.513 | 0.166–1.587 |

| IV | 0.057 | 2.855 | 0.969–8.412 | 0.084 | 2.465 | 0.885–6.866 |

| Radiation | ||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No/unknown | 0.007 | 2.035 | 1.220–3.395 | 0.004 | 1.998 | 1.247–3.203 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No/unknown | <0.0001 | 0.181 | 0.087–0.375 | <0.0001 | 0.199 | 0.107–0.370 |

| Regional lymph nodes removal | ||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No | 0.657 | 1.148 | 0.623–2.117 | 0.846 | 1.057 | 0.604–1.850 |

| Tumor size | ||||||

| 1–10 mm | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 11–20 mm | 0.040 | 2.627 | 1.045–6.605 | 0.045 | 2.697 | 1.023–7.110 |

| 21–40 mm | 0.022 | 2.833 | 1.163–6.896 | 0.024 | 2.960 | 1.151–7.607 |

| >40 mm | 0.006 | 3.587 | 1.446–8.896 | 0.005 | 3.829 | 1.492–9.824 |

DSW – divorced, separated or widowed.

Due to the prognostic factor of age changing in the observation period and causing variations in other prognostic factors, the age was used as a time-varying covariate to repeat the results of Fine-Gray model analysis. The statistically significant factors affecting PTAC when age was used as a time covariate were poorly differentiated grade [versus well-differentiated grade: hazard ratio (HR)=6.070, 95% confidence interval (CI)=3.339–11.034], undifferentiated grade (versus well-differentiated grade: HR=8.010, 95% CI=3.689–17.394), no chemotherapy (versus receiving chemotherapy: HR=0.268, 95% CI=0.131–0.548), unknown chemotherapy status (versus receiving chemotherapy: HR=3.518, 95% CI=2.890–41.743), AJCC stage IV (versus stage I: HR=3.583, 95% CI=1.172–10.956), regional metastasis (versus localized: HR=2.577, 95% CI=1.497–19.478), and distant metastasis (versus localized: HR=3.518, 95% CI=2.890–41.743). Neither the linear term (P=0.65) nor the quadratic term (P=0.67) expressing the interaction of time with age was statistically significant. The data are provided in detail in Table 4.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis by Bayesian Information Criterions for competing risk.

| Variables | Z | P | HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age.t | 0.447 | 0.65 | 1.001 | 0.998–1.003 |

| Age.t2 | −0.423 | 0.67 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 |

| Grade | ||||

| Well differentiated | Reference | |||

| Moderately differentiated | 0.866 | 0.39 | 1.336 | 0.693–2.576 |

| Poorly differentiated | 5.915 | <0.0001 | 6.070 | 3.339–11.034 |

| Undifferentiated | 5.260 | <0.0001 | 8.010 | 3.689–17.394 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | Reference | |||

| No/unknown | −3.609 | 0.0003 | 0.268 | 0.131–0.548 |

| AJCC | ||||

| I | Reference | |||

| II | 1.588 | 0.11 | 3.346 | 0.753–14.860 |

| III | −0.582 | 0.56 | 0.690 | 0.198–2.409 |

| IV | 2.238 | 0.025 | 3.583 | 1.172–10.956 |

| Stage | ||||

| Localized | Reference | |||

| Regional | 5.400 | 0.01 | 2.577 | 1.497–19.478 |

| Distant | 10.983 | 0.0004 | 3.518 | 2.890–41.743 |

Discussion

This study aimed to identify accurate prognostic factors for PTAC-specific death using a competing-risks model based on data in the SEER database. We found that being older, male, having regional or distant metastasis, a worse differentiation grade, not receiving radiation therapy, receiving chemotherapy, and having a larger tumor are the independent risk factors for PTAC-specific death.

Deaths from PTAC and other causes are not independent, since the former cannot happen once the latter has occurred. This situation is inconsistent with the assumptions underlying Cox regression, and so applying Cox regression might produce incorrect HR values or even inaccurate information about the impact of a single factor. The results obtained in the traditional Cox regression differed from those obtained using a competing-risks model in this study. Although the risk factors identified using the Cox regression model did not differ markedly from those revealed using the competing-risks model, their HR values were different. In addition, marital status was found to be a prognostic factor in Cox regression, with being separated/divorced/widowed increased the risk of death in PTAC patients compared with being married.

Age is a factor that changes with time and may cause variations in other prognostic factors. Tran et al. found that age affects the prognostic impact of tumor size in PTC [16], and so age was treated as a time covariate in the present study, which revealed that after excluding the effects of age, worse differentiation grade, receiving chemotherapy, higher AJCC stage, and metastasis still increase the risk of PTAC-specific death. Tumor size was not included in the competing-risks model with age as a time covariate, but we speculate that there are significant interactions between age and tumor size.

Most previous studies have found male sex to be a significant prognostic factor for a poor outcome in PTC [17–19]. A meta-analysis found that being male was a very powerful prognostic factor, with increasing the recurrence risk by up to 50%. Its power was even bigger than age [17]. However, contradictory results have also been reported. Oyer et al. reported that being male was not a recurrence risk factor in patients older than 45 years old with differentiated thyroid carcinoma [20]. In addition, Nilubol et al., using the data of SEER database, actually found that being male was not an independent prognostic factor for thyroid follicular cells [21]. These conflicting results may be due to differences in the pathological types of thyroid cancer. Indeed, Lee et al. found that male sex was a poor prognostic factor in PTC but not in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma [22]. In the present study we found that although there were more females than males with PTAC, males had a higher risk of death than females in the competing-risks model. We speculate that the effect of being male on the prognosis of thyroid cancer is greatly affected by the underlying pathology, and that this effect may interact with age.

It should be noted that our study mainly targeted patients with thyroid cancer after surgery, which was due to most patients with thyroid cancer first receiving surgical treatment. Some patients do not receive surgery for various reasons. Ho et al. used SEER data to investigate the mortality risk of nonoperative PTC. They stratified patients into nonsurgical and surgical management, and found that increasing age and tumor size lead to a progressively higher mortality risk without surgery, but only beyond thresholds of age >56 years and tumor size >6.1 mm [23]. Feng et al. also found that not receiving surgery was a risk factor for PTC-specific mortality among patients younger than 55 years. Surgery might therefore be appropriate for PTC patients regardless of age [24].

Few studies have researched the prognostic factors for PTAC, with most research focusing on PTC and applying Cox regression models. These studies have found that the significant factors include age [25], multifocality [26], metastases [27], extrathyroidal extension [28], tumor size, and certain genes [29]. While some potentially important variables are not included in the SEER database, our results obtained using a Cox regression model of the prognosis factors for PTAC are basically consistent with the literature reports on PTC. It should also be noted that only relatively minor differences were found for the risk factors between our competing-risks model and the Cox regression model. This might be due to PTAC having a lower risk of death. However, when a competing event exists, it is more accurate to use competing-risk models to analyze prognostic factors, both for risk factors and their HRs.

The limitations of this study cannot be ignored. Firstly, thyroid cancer is a disease with a high recurrence rate, indicating the importance of studying the risk of recurrence; however, this variable is not collected in the SEER database. Another limitation is the relatively short follow-up period (2010–2015). Because the overall prognosis of PTAC is generally favorable, the incidence of PTAC-specific death is low in a short time. Thirdly, some factors, such as vascular invasion, family history, molecular markers, and other histological findings, were not evaluated in our study.

Conclusions

This study has found that age, sex, metastasis, differentiation grade, radiation status, chemotherapy status, and tumor size are independent risk factors for the postoperative prognosis of patients with PTAC in the presence of competing risks. Our findings may be useful for improving patient prognoses and decision-making when providing individualized treatments.

Footnotes

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of interests

None.

Source of support: This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 16BGL183)

References

- 1.Kocsis-Deak B, Arvai K, Balla B, et al. Targeted mutational profiling and a powerful risk score as additional tools for the diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020;26:101–8. doi: 10.1007/s12253-019-00772-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roman BR, Morris LG, Davies L. The thyroid cancer epidemic, 2017 perspective. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24:332–36. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conzo G, Avenia N, Bellastella G, et al. The role of surgery in the current management of differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocrine. 2014;47:380–88. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajeer MH, Awad HA, Abdullah NI, et al. The rising trend in papillary thyroid carcinoma. True increase or over diagnosis? Saudi Med J. 2018;39:147–53. doi: 10.15537/smj.2018.2.21211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Vasilyeva E, Wiseman SM. A current perspective on galectin-3 and thyroid cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2019;19:1017–27. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2019.1693270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fayek IS. Prophylactic level VII nodal dissection as a prognostic factor in papillary thyroid carcinoma: A pilot study of 27 patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:4211–14. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.10.4211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sung TY, Kim M, Kim TY, et al. Negative expression of CPSF2 predicts a poorer clinical outcome in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2015;25:1020–25. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bothra S, Chekavar A, Mayilvaganan S. Prognostic significance of the proportion of tall cell components in papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg. 2017;41:2644. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-3945-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming TR, Lin DY. Survival analysis in clinical trials: Past developments and future directions. Biometrics. 2000;56:971–83. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.0971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: Competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007;26:2389–430. doi: 10.1002/sim.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP. Competing risk of death: An important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:783–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Chen T, Zeng W, et al. A SEER database analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11412. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11788-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng J, Shen F, Cai W, et al. Survival of aggressive variants of papillary thyroid carcinoma in patients under 55 years old: A SEER population-based retrospective analysis. Endocrine. 2018;61:499–505. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1644-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cederkvist L, Holst KK, Andersen KK, Scheike TH. Modeling the cumulative incidence function of multivariate competing risks data allowing for within-cluster dependence of risk and timing. Biostatistics. 2019;20:199–217. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxx072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin PC, Fine JP. Practical recommendations for reporting Fine-Gray model analyses for competing risk data. Stat Med. 2017;36:4391–400. doi: 10.1002/sim.7501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran B, Roshan D, Abraham E, et al. The prognostic impact of tumor size in papillary thyroid carcinoma is modified by age. Thyroid. 2018;28:991–96. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo K, Wang Z. Risk factors influencing the recurrence of papillary thyroid carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5393–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruijff S, Petersen JF, Chen P, et al. Patterns of structural recurrence in papillary thyroid cancer. World J Surg. 2014;38:653–59. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu XM, Wan Y, Sippel RS, Chen H. Should all papillary thyroid microcarcinomas be aggressively treated? An analysis of 18,445 cases. Ann Surg. 2011;254:653–60. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318230036d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oyer SL, Smith VA, Lentsch EJ. Sex is not an independent risk factor for survival in differentiated thyroid cancer. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2913–19. doi: 10.1002/lary.24018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilubol N, Zhang L, Kebebew E. Multivariate analysis of the relationship between male sex, disease-specific survival, and features of tumor aggressiveness in thyroid cancer of follicular cell origin. Thyroid. 2013;23:695–702. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YH, Lee YM, Sung TY, et al. Is male gender a prognostic factor for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma? Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:1958–64. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho AS, Luu M, Zalt C, et al. Mortality risk of nonoperative papillary thyroid carcinoma: A corollary for active surveillance. Thyroid. 2019;29:1409–17. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng J, Shen F, Cai W, et al. Survival of aggressive variants of papillary thyroid carcinoma in patients under 55 years old: A SEER population-based retrospective analysis. Endocrine. 2018;61:499–505. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1644-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan H, Winchester DJ, Prinz RA, et al. Differences in the impact of age on mortality in well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3193–99. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6668-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markovic I, Goran M, Besic N, et al. Multifocality as independent prognostic factor in papillary thyroid cancer – a multivariate analysis. J Buon. 2018;23:1049–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maksimovic S, Jakovljevic B, Gojkovic Z. Lymph node metastases papillary thyroid carcinoma and their importance in recurrence of disease. Med Arch. 2018;72:108–11. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2018.72.108-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Londero SC, Krogdahl A, Bastholt L, et al. Papillary thyroid carcinoma in Denmark, 1996–2008: Outcome and evaluation of established prognostic scoring systems in a prospective national cohort. Thyroid. 2015;25:78–84. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen L, Qian C, Cao H, et al. Upregulation of the solute carrier family 7 genes is indicative of poor prognosis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:235. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1535-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]