Abstract

Men are consistently overrepresented in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severe outcomes, including higher fatality rates. These differences are likely due to gender-specific behaviors, genetic and hormonal factors, and sex differences in biological pathways related to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Several social, behavioral, and comorbid factors are implicated in the generally worse outcomes in men compared with women. Underlying biological sex differences and their effects on COVID-19 outcomes, however, have received less attention. The present review summarizes the available literature regarding proposed molecular and cellular markers of COVID-19 infection, their associations with health outcomes, and any reported modification by sex. Biological sex differences characterized by such biomarkers exist within healthy populations and also differ with age- and sex-specific conditions, such as pregnancy and menopause. In the context of COVID-19, descriptive biomarker levels are often reported by sex, but data pertaining to the effect of patient sex on the relationship between biomarkers and COVID-19 disease severity/outcomes are scarce. Such biomarkers may offer plausible explanations for the worse COVID-19 outcomes seen in men. There is the need for larger studies with sex-specific reporting and robust analyses to elucidate how sex modifies cellular and molecular pathways associated with SARS-CoV-2. This will improve interpretation of biomarkers and clinical management of COVID-19 patients by facilitating a personalized medical approach to risk stratification, prevention, and treatment.

Article Highlights.

-

•

Most biomarkers associated with severe Covid-19 disease differ by sex when examined in experimental and epidemiological studies in the non-COVID-19 population.

-

•

Sex specific genetic and hormonal modulation of the immune and renin angiotensin aldosterone system are complex, but important COVID-19 disease mechanisms which may provide insight into the observed sex disparity in case fatality rates.

-

•

Future studies should address the relationship between biomarkers and COVID-19 disease severity including mortality, as current data are scarce.

Reporting of disaggregated data by sex is uncommonly performed in the available literature, and current data relating to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and attendant outcomes are no exception.1 The Global Health 50/50 have collated international data from countries that provide sex-specific information and report a male-to-female case fatality ratio ranging from 1.6 to 2.8.2 National data from China, Korea, and Europe report similar case fatality ratios and also a possible interaction with age.3 , 4 Results from observational studies have been consistent, with males and older persons tending to be overrepresented among patients with severe disease,5, 6, 7 intensive care unit admissions,5 , 8, 9, 10 and death from the infection.3 , 7 , 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Studies stratified by sex have also identified male sex as a risk factor for worse outcomes and increased mortality.16, 17, 18, 19 Large, robust sex-stratified analyses, however, are limited due to the nature of studying an emerging disease.

The sex disparity of COVID-19–related morbidity and mortality is likely explained by a combination of biological sex differences (differences in chromosomes, reproductive organs, and related sex steroids) and gender-specific factors (differential behaviors and activities by social and cultural/traditional roles).4 Men are more likely to engage in poor health behaviors such as smoking and alcohol consumption,20 , 21 and have higher age-adjusted rates of pre-existing co-morbidities associated with poor COVID-19 prognosis, including hypertension, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).7 , 9 , 13 , 18 , 22, 23, 24 Furthermore, a stratified analysis by sex showed that even after adjustment for age, the effect of co-morbidities on COVID-19 mortality was greater for men than women.16

Various biological pathways may contribute to the differing responses to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus by sex. The size and independence of the effect of sex on the association between biomarkers and COVID-19 health outcomes, however, rarely have been rarely reported or translated into preventive and clinical care settings. This review synthesizes the available evidence regarding the proposed cellular and molecular markers of COVID-19 severity by sex, including biomarkers of inflammation; coagulation; liver, renal, and cardiac function; and expressions of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2). The available literature on such markers in the general population will also be discussed. The literature regarding biomarkers and COVID-19 available on PubMed, Embase, and the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure published until June 7, 2020, was systematically searched and reviewed. Our review synthesizes the current data and identifies the gaps in knowledge regarding the sex differences in COVID-19, which should be addressed in current and future studies to personalize evolving screening, preventive, and treatment strategies.

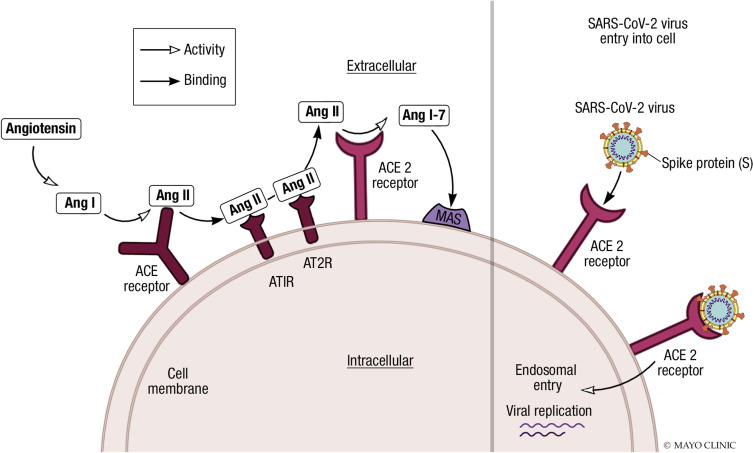

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System and SARS-COV-2 Viral Cell Entry

The pathogenesis of SARS-CoV2 disease involves tissues which express high levels of the ACE2 receptor. The infection typically starts in the oropharynx or nasopharynx, and then spreads to tissues that express ACE2: involvement of the upper airway and lungs occurs, the latter potentially leading to pneumonitis. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a key negative regulator of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and counterbalances the actions of angiotensin-converting enzymes (ACEs) (Figure ). The ACE converts angiotensin I (Ang I) to angiotensin II (Ang II), which binds to the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R). This induces many deleterious effects, including vasoconstriction, fluid retention, enhanced cellular growth and migration, and oxidative stress promoting fibrosis and inflammation.25 Angiotensin-converting enzyme and ACE2 share substantive sequence identity, but ACE2 shows substrate specificity and functions exclusively as a monocarboxypeptidase. It removes single C-terminal amino acids from Ang II, generating Ang 1-7 which binds and activates the G-protein–coupled Mas receptor. Angiotensin 1-7 attenuates the harmful effects of Ang II by eliciting a range of effects on the cardiovascular system, including vasodilatation; myocardial protection; and effects that are anti-arrhythmic, anti-hypertensive, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic, and inotropic in nature. Angiotensin 1-7 also inhibits pathologic cardiac remodeling and insulin resistance.26 , 27

Figure.

Cellular receptors of angiotensin II and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral entry. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) removes C-terminal amino acids from angiotensin II (Ang II), generating Ang 1-7 which activates MAS receptors. Ang 1-7 has a range of cardiovascular protective effects, thus attenuating the effect of Ang II. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is primed by transmembrane serine protease 2 (not shown in figure) and interacts with the cell surface ACE2 receptor facilitating endosomal entry. AT1R = angiotensin type 1 receptor; AT2R = angiotensin type 2 receptor.

The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein interacts with the human cell surface ACE2 receptor, whereas TMPRSS2 primes the spike protein and may cleave the S1/S2 and S2’ sites to assist attachment and membrane fusion.28 , 29 Viral invasion increases activity of A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17, which mediates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and ectodomain shedding of ACE2, reducing ACE2 cell surface expression.27 The protective regulatory effect of the ACE2/Ang 1-7 axis against the RAAS is therefore lost.

ACE2 and TMPRSS2: Sex Differences in Expression and Regulation

Increasing evidence supporting the roles of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in viral entry and invasion of cells has led to numerous animal and human studies aiming to elucidate the relationship between their expressions/functions and risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 severity. In addition, given previously known male/female differences in RAAS,30 possible sex differences in ACE2 and TMPRSS2 have been postulated, but data are limited. It is likely that chromosomal/genetic differences, together with differential regulation of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 by sex hormones, which is life-cycle dependent, may be relevant considerations. Notably, the ACE2 gene lies on the X chromosome and escapes X-chromosome inactivation; however, sex-specific expression is inconsistent across multiple different tissues.31 The receptor is predominantly expressed in the lung, heart, vascular endothelium, kidney, testis, and gastrointestinal tract and is also shed into circulating plasma.27

Estrogen through estrogen-receptor signaling on myocardium may decrease the ratio of ACE to ACE2 expression and upregulate Mas and angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2R) expression levels,32 which, unlike the effect of AT1R activation as described above, reduces inflammation and tissue fibrosis and promotes tissue repair.33 However, a subsequent study showed no significant difference in ACE2 expression values in left ventricular tissue between males and females.34 Preliminary results of an integrated bio-informatics analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data indicate that the expression of androgen receptors positively correlates with ACE2 and that men may have increased pulmonary alveolar type II cells expressing ACE2 compared with women.35 Other studies, in contrast, report no significant difference in lung tissue gene expression between males and females, or with differences in age.34 , 36 , 37 Smoking status, however, appears to correlate with ACE2 gene expression thus implicating differences in gender-specific behaviors. Current smokers as compared with never smokers have significantly upregulated ACE2 expression in the lung and oral epithelium.37, 38, 39 COPD also has been independently associated with increased ACE2 expression by approximately 50% compared with those without COPD.38 Given that smoking and COPD are more prevalent among males, higher expression of ACE2 due to these risk factors may, in part, explain the worse outcomes of COVID-19 in males. In summary, although studies have reported inconsistent sex differences related to ACE2 expression, it seems that, in general, ACE2 expression is increased in men and decreased in women. These effects may be modified/potentiated by gender-specific factors/behaviors, and should be investigated in future studies dedicated to sex differences.

Observed sex-related differences in the severity of COVID-19 may also be mediated via TMPRSS2 gene expression and activity. The expression of TMPRSS2 on non–sex-specific tissues does not appear to significantly differ between males and females.34 However, the only known stimulus of TMPRSS2 gene transcription is androgens40 and, interestingly, patients with COVID-19 who required hospital admission exhibit androgenic alopecia.41 TMPRSS2 is a recognized protease associated with prostate cancer, and males with prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy may be at a significantly lower risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with male patients who are not.42 In addition, one haplotype that upregulates TMPRSS2 expression did so in response to androgens, whereas another is associated with increased risk of severe influenza, the latter also disproportionately affecting males.43 , 44 The risk of severe infection mediated by androgen levels may, in part, explain why preadolescents are usually not severely affected by infection with SARS-CoV-2. However, studies directly comparing the expression of TMPRSS2 by sex and COVID-19 outcomes have not yet been conducted. Future investigation of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expressions in various tissues and further stratification by sex with respect to disease severity is required.

Immunological and Inflammatory Biomarkers

Morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 is mediated through intense viral stimulated inflammation and increasing levels of inflammatory biomarkers and cytokines, commonly referred to as “cytokine storm.” Together with reduced lymphocyte counts, cytokine storm is consistently associated with more severe COVID-19 disease. Among those exhibiting an excessive inflammatory profile, older and male patients are overrepresented.7 , 45 , 46

An early elevation in C-reactive protein (CRP) greater than 15 mg/L provides a marker of disease severity46 and levels greater than 200 mg/L on admission are independently associated with five times the odds of death.7 Males with severe COVID-19 reportedly have a higher CRP concentration compared with females, independent of age and co-morbidities.19 Of the numerous interleukins (IL)–associated with COVID-19 severity, including IL-6, IL-2, IL-8, IL-10,45, 46, 47 and compared with females, young and old males with COVID-19 exhibit significantly higher IL-2 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), respectively, independent of co-morbidities.19 Moreover, data indicate that males with COVID-19 display greater upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including CCL14, CCL23, IL-7, IL-16, and IL-18, the latter possibly contributing to their higher susceptibility to developing cytokine storm and subsequent poorer COVID-19 outcomes.35 Although IL-10, a cytokine with anti-inflammatory effects, has been shown to be higher among older males, a positive IL-10 feedback could be considered an attempt to decrease excessive inflammation and consequent tissue damage. Further, higher IL-10 expression diminishes the activity of antiviral T-cells.48 , 49 Whether biological sex differences modify the associations among CRP and ILs and COVID-19 outcomes has yet to be examined.

Adaptive Immune Response

Lymphocytes are among the first responders to viral agents, including SARS-CoV-2, and are associated with COVID-19 severity.50 Although mild COVID-19 disease can be associated with either increased or decreased lymphocyte counts,51 in severe disease, lymphocytes are consistently decreased. Although some COVID-19 studies have suggested that male sex is inversely associated with lymphocyte count,17 , 19 a meta-analysis of the mean difference in admission lymphocyte counts between patients with and without severe COVID-19 outcomes showed that lymphopenia and disease severity were not modified by sex or co-morbidities.52

A single-center Wuhan study showed that in ill patients, concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G were significantly higher in females compared with males, and remained so until 4 weeks from hospital admission.53 Sex-specific adaptive immune response is generally well recognized, with women mounting higher antibody production54 and more efficacious vaccine responses.54 Healthy females are known to have higher numbers of CD4+ T cells, greater CD4+: CD8+ ratios, and increased numbers of activated T cells, cytotoxic T cells, and B cells compared with males,54, 55, 56, 57 resulting in a prompt response to the presence of infectious agents. The role of sex steroids in the differential immune responses is supported by a study indicating testosterone exerts an immunosuppressant effect, whereas estrogen may be either immune enhancing58 or immunosuppressive.59

Innate Immune System

Total white cell count was less consistently elevated among COVID-19 patients who required intensive care unit admission or died compared with patients who did not.12 , 46 , 51 , 60 These studies did not investigate the effect of sex on this relationship, a question that merits attention as there are sex-specific differences in blood leukocyte composition within the general population. In the latter population, males have higher baseline numbers of total leukocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils compared with females. The total leukocyte and neutrophil counts increase progressively until the age of 55 years in males. Women have a bimodal distribution in total leukocyte counts, with the lowest counts occurring around menopause.61 , 62 These known sex differences, together with the presence of underlying co-morbidities and concurrent infections, likely contribute to the inconsistent findings regarding white blood cell counts reported in current COVID-19 studies.

The neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a well-known marker of inflammation and appears to reflect the severity of COVID-19, particularly among patients older than 50 years of age.51 , 63 A single-center retrospective analysis observed that more males had an NLR above 11.75, which was associated with a lower survival rate.64 The NLR exhibits distinct sexual dimorphism in the general population. Females 50 age years or younger have a higher NLR compared with males of the same age and compared with older females. The NLR is higher for males than females older than the age of 50 years.61 The effects of sex and age on the prognostic value of NLR require further investigation.

Sex differences may have important implications in the efficacy of therapeutics that target particular viral signaling pathways. Notably, toll-like receptors (TLRs), which upregulate type 1 interferon (IFN), an important protective mechanism against viral infections,65 may be up to 10-fold higher in females compared with males.66, 67, 68, 69 Furthermore, a recent study reported that after TLR7 stimulation, IFN levels were lower in men compared with women. Toll-like receptor 7–mediated IFN expression may be decreased in men due to the known negative effects of testosterone on IFN expression.68 IFN therapy is under active investigation for COVID-19 patients, so additional research addressing sex differences in the IFN pathway may result in a targeted, sex-dependent therapeutic approach.

In addition to deriving benefit from the specific effects of estrogen, females may have stronger immune responses due to the intrinsic differences in the expression of genes on the sex chromosomes. Notably, several genes which contain high numbers of immune-related alleles responsible for innate and adaptive immune responses to infection are located on the X chromosome.70 Although X-chromosome inactivation is a mechanism of equalizing gene expression in females and males, some genes such as TLR771 may escape silencing, thereby conferring on females an immune advantage over males.70

Sex-Specific Conditions and COVID-19

Reproduction

One physiologic state that is associated with upregulation and increase in ACE2 is normal gestation, which raises the possibility that pregnant women may be at a greater risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection. We have recently reviewed the topic of pregnancy, its complications, and COVID-19.72 Briefly, the upregulation of ACE2 and consequent conversion of Ang II to Ang 1-7 promote a general state of vasodilation with anti-thrombotic and anti-inflammatory activities in uncomplicated pregnancies. Pre-eclampsia is a pregnancy-specific, multi-system condition caused by abnormal placental vascular remodeling and systemic endothelial dysfunction which affects 3.3% of pregnancies,73 and is characterized by decreased maternal plasma Ang 1-7 levels. SARS-CoV-2 directly binds and downregulates ACE2 expression; accordingly, ACE2 protein expression is expected to decrease during such infection. In pregnancy, this may potentiate these RAAS abnormalities because increased Ang II levels, relative to decreased Ang 1-7 levels, occur in pre-eclampsia (Figure).72 Because of the overlapping mechanisms, certain clinical features and lab abnormalities, including thrombocytopenia74 and liver function derangement,75 may be seen in both pre-eclampsia and COVID-19, making the distinction between COVID-19 plus pre-eclampsia versus COVID-19 only complicated.76 Consequently, pregnant women with COVID-19 must be evaluated critically, with particular consideration as to whether pre-eclampsia concomitantly exists or is incipient.

Sex Hormones, Menopause, and Hormone Replacement Therapy

Sex differences that are constant throughout the life cycle are likely chromosomal/genetic in origin, whereas those that occur with puberty and then fade with aging are suggestive of hormonal effects. Sex steroids, including testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone are potent regulators of immune and inflammatory responses due to the presence of sex-hormone responsive sequences in the respective genes. Estrogen during pre-menopause has anti-inflammatory effects, attended by lower levels of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-alpha.77 Conversely, the physiologic decline of estrogen levels during natural menopause results in increased levels of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-alpha.59 Estrogen depletion or oophorectomy in mice infected with SARS-CoV led to a worse prognosis compared with normal estrogen producing mice.78 Clinical studies show that inflammation resolves more rapidly in women as compared with men, and these differences are thought to be due to hormonal effects on neutrophil apoptosis and bone marrow production.79 , 80 Taken together, available studies provide strong evidence that estrogen exerts significant anti-inflammatory responses, thus suggesting a potential therapeutic role of hormone replacement therapy in older women. Similarly, low levels of testosterone in elderly men have been associated with upregulation of inflammatory markers and possible increased risk of lung damage, as well as respiratory muscle catabolism and increased need for assisted ventilation.81 As advanced age remains one of the most important risks for poor COVID-19 outcomes, future research should address the role of hormone replacement therapy in elderly women and men who are diagnosed with COVID-19.

Markers of Calcium Homeostasis and COVID-19

Procalcitonin

Procalcitonin (PCT) is the precursor of calcitonin, a hormone that regulates calcium and phosphorus homeostasis by opposing the action of parathyroid hormone. Procalcitonin levels are higher in severe cases of COVID-19.7 , 82, 83, 84 Several meta-analyses showed that the risk of severe infection may be five-fold higher in patients with elevated levels of PCT.83, 84, 85 Serum PCT levels are low in healthy persons and an elevated PCT level of greater than or equal to 0.5 ng/mL is typically considered a sign of bacterial but not viral infection.86 , 87 Although no difference in PCT levels by sex occurs in healthy individuals,88 one study of PCT levels in 14 patients with critical COVID-19 infection described that more males had a PCT level greater than or equal to 0.5 ng/mL compared with females.17 Given this association with outcomes in COVID-19, ongoing studies should investigate the role of PCT as a sex-specific prognostic marker of disease severity.

Vitamin D

Apart from its role in calcium homeostasis through improving calcium reabsorption from the gut, vitamin D modulates inflammatory pathways associated with viral infections.89 Meta-analyses indicate that vitamin D deficiency increases the risk of acute viral respiratory infection and community-acquired pneumonia, and that supplementation may prevent upper respiratory tract infections.90 Vitamin D was found to decrease with age, and the strongest protective effect of supplementation was observed in those with the lowest 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels at baseline.91 , 92 Whether sex modified the effect of supplementation on upper respiratory tract infection risk was not examined.92 , 93 American men are uncommonly evaluated for this deficiency and often do not receive adequate supplementation, especially those who are older or obese.94

Ecological studies suggest a positive correlation between countries with low mean concentrations of 25(OH)D and higher COVID-19 infection and mortality rates.95 , 96 A Swiss cohort study of 109 patients reported that 25(OH)D levels were significantly lower in patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with those who were uninfected, although the association did not significantly differ when stratified by sex and age older than 70 years.97 A larger analysis of 348,598 UK Biobank participants confirmed that despite a univariate association between 25(OH)D levels and the odds of COVID-19, following multivariable adjustment, the association was no longer significant. Modification by age or sex was not investigated.98 It is plausible that lower vitamin D levels may contribute to worse disease observed in older men compared with younger or female individuals,90 , 93 but there is insufficient epidemiologic evidence in support of this thesis. Given the relatively minimal risks of vitamin D supplementation, some experts have recommended vitamin D supplementation as a COVID-19 preventive strategy, especially in at risk elderly populations.91

Organ-Specific Biomarkers

Cardiac Biomarkers

Patients with COVID-19 may suffer direct cardiac damage or damage from associated systemic inflammation, hemodynamic instability, and multiple organ failure.99, 100, 101 Cardiac biomarkers are routinely reported among hospital cohorts, and meta-analyses and subsequent studies have shown that mean levels of troponin,7 , 101, 102, 103, 104, 105 N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), and creatine kinase myocardial band101 , 103 , 105 were all significantly higher in patients with more severe COVID-19. Furthermore, elevated troponin levels diagnostic of acute cardiac injury were associated with severe disease and at least a four-fold higher mortality.102 , 103 These patients tended to be older, male, and have a history of CVD.101 , 103 The most recent meta-analysis, however, reported that the standard mean difference of troponin and BNP levels between severe and less severe COVID-19 infections was modified by hypertension, but not by age, sex or other co-morbidities.103 Subsequent studies of NT-proBNP, high sensitivity (hs)-troponin levels and COVID-19 outcomes also observed no association with sex.17 , 106 , 107 Among healthy individuals, baseline levels of cardiac biomarkers significantly differ by sex. For example, in females compared with age-matched males, hs-troponin and creatine kinase myocardial band levels are lower, whereas NT-proBNP levels are higher.108 , 109 However, in an acute setting, sex-specific hs-troponin and NT-proBNP thresholds do not improve their predictive value of myocardial infarction or death.109, 110, 111 Despite women having higher baseline NT-proBNP, in the setting of acute heart failure the absence of an NT-proBNP sex difference is likely because women more commonly have preserved ejection fraction and less of an increase in NT-proBNP levels compared with men who are more likely to develop low ejection fraction heart failure and greater elevations in NT-proBNP levels.106 , 111 In addition, NT-proBNP levels are thought to be inversely related to androgen levels. Thus, the baseline sex difference is less pronounced as women and men age because estrogen levels decline in women and androgen levels decrease in men.112 Similar to non-COVID patients, sex was not shown to modify the association between cardiac biomarker levels and patient outcomes among COVID-19 patients in the acute hospital setting.103

Liver Function

SARS-CoV-2 causes liver damage through varied mechanisms, from direct cellular toxicity to the effects of immune-related inflammation; concomitant drug toxicity may contribute to liver damage in patients with COVID-19.75 Several studies reported increased levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of between 14% and 53% in COVID-19–affected patients. Significantly higher plasma levels associate with more severe infection and, in some studies, with mortality.10 , 12 , 16 , 75 , 113, 114, 115 One study of 168 patients critically ill with COVID-19 reported significantly higher levels of ALT and AST in males compared with females.17 Serum transaminase concentrations are generally lower in females compared with males,116, 117, 118, 119 in part due to differences in fat to muscle ratio, lipid metabolism, and hormonal effects on liver cells.119 Premenopausal women are at lower risk of development of liver inflammation, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and the resulting increase in cardiovascular risk.120 Furthermore, elevated ALT may be a predictor of coronary artery disease in males only.121 With limited reporting on sex differences in liver markers, it is difficult to identify an effect of sex on the prognostic potential of transaminases in COVID-19 patients.

Renal Function

Renal injury occurs in COVID-19. A large prospective cohort study of 701 patients in Wuhan, China, noted that acute kidney injury (AKI) occurred in 5% of patients.122 This is a lower percentage than is usually observed in other critical illnesses, and renal autopsies performed on COVID-19 patients with AKI showed evidence of renal histologic injury, with varying degrees of acute tubular necrosis.123 Biomarkers of renal impairment, including an increase in creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and presence of AKI have been reported in most studies.16 , 113 , 122 , 124 , 125 Greater elevations in these renal biomarkers, along with proteinuria, and hematuria, occur in critically ill patients compared with patients with mild or moderate infection.7 , 123 Furthermore, independent of age and sex, a higher baseline creatinine, underlying proteinuria, and hematuria were associated with a higher risk of mortality.12 , 46 , 123 , 124 In patients with severe disease, creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels were consistently higher in men compared with women,17 and older males were more likely to have a higher baseline creatinine and develop AKI,17 , 124 although studies have not investigated the effect of sex on renal biomarkers and COVID-19 severity.

Serum creatinine levels are affected by many factors including, age, sex, and muscle mass. The literature regarding susceptibility to AKI based on sex is controversial. A woman’s hormonal environment, however, is thought to have a protective effect against the development of AKI,126 , 127 and females have been previously shown to be at lower risk of AKI compared with males.126 Similarly, smaller studies of renal transplantation patients have suggested that male sex may be a risk factor for AKI in COVID-19.128, 129, 130, 131 These data set the stage for future studies that should be adequately powered, and likely multicenter, to address how the interplay between sex and COVID-19 may affect the incidence of kidney dysfunction, both in native and transplanted kidneys.

Coagulation Biomarkers

Thrombotic diatheses are commonly observed in persons with severe COVID-19.132 , 133 COVID-19 patients with thrombotic complications generally follow a course of disease that is more aggressive. In one study, 71% of patients who died of COVID-19 fulfilled the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis criteria for disseminated intravascular coagulopathy compared with just 0.6% of survivors.134 Moreover, evidence consistently shows the negative prognostic value of individual coagulation parameters, including elevated D-dimer12 , 46 , 85 , 135 , 136 and reduced platelet counts,45 , 46 , 74 , 135, 136, 137, 138 both of which were significant after adjustment for multiple confounders.139

In studies of COVID-19 patients with coagulation dysfunction, the composition of the patient population more commonly includes male patients, and possibly reflects the more severe disease that occurs in males.12 , 85 , 138 The underlying mechanism of coagulopathy in COVID-19 patients has yet to be elucidated, but it is hypothesized that a disproportionate inflammatory response results in endothelial cell dysfunction and a pro-thrombotic state.140 Because of ACE2 receptor expression on endothelial cells, the COVID-19 virus may cause endotheliitis, which could result in not only arterial and venous inflammation, but also microcirculatory and lymphocytic endotheliitis; the consequences of such endotheliitis include widespread organ involvement, sudden vasoconstriction, abnormal angiogenesis, micro-thrombi formation, and ischemia.140, 141, 142 Moreover, patients with severe COVID-19 develop a hypercoagulable state,143 further demonstrated by increased levels of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor, marginally decreased anti-thrombin III activity,144 and inactivation of the fibrinolytic system.145 These derangements likely underlie venous thromboses; arterial thromboses that may present as ischemic stroke, mesenteric ischemia and acute limb ischemia; and the phenomenon of free-floating thrombi observed in COVID-19 infection–related thrombotic events.133 , 146, 147, 148, 149

Studies of coagulation factors in the general population have consistently shown more favorable profiles for female subjects, and particularly for young women of premenopausal age; such profiles may confer lower risks for thrombotic events compared with men (Table ). Future investigation into the associations of coagulation markers with respect to COVID-19 severity and sex differences would improve understanding of the disease pathology and inform treatment options.

Table.

Coagulation Biomarkers, Sex, and Age Differencesa

| Coagulation biomarker | Sex with higher biomarker levelb | Advancing age |

|---|---|---|

| Primary hemostasis | ||

| Platelet count | Female150 | Decrease150 |

| Estrogen receptor associated platelet protein expression | Equal151 | |

| VSM estrogen receptor beta: alpha ratio | Female152,c | |

| NO mediated vasodilation | Female153, 154, 155 | |

| Platelet adherence + spreading response to vascular injury | Male156 | |

| Platelet aggregation | Equal156 | |

| Secondary hemostasis | ||

| Factor VII | Female157 | Increase157 |

| Factor VIII | Female157,158,d | Increase157,158 |

| Factor IX | Equal157 | Increase157 |

| vWF | Female158,d | Increase158 |

| Fibrinogen | Female157,d,e | Increase157 |

| PT | Equal159 | |

| aPTT | Equal159 | |

| Fibrinolysis | ||

| Clot lysability | Equal160 | |

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 antigen | Male161 | Increase161,f |

| Tissue plasminogen activator antigen | Male161 | Increase161,f |

| Protein C/S levels | Varies by age157 | Increase157,g |

| D-dimer | Female162 | Increase163,164 |

| General | ||

| VTE | Male165,h | |

| VTE recurrence | Male166 | |

| Ischemic stroke incidence | Male167,i | |

| Hemodynamically significant coronary stenosis at first MI in age <45 years | Male168 |

aPTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; MI = myocardial infarction; NO = nitric oxide; PT = prothrombin time; VSM = vascular smooth muscle; VTE = venous thromboembolism; vWF = von Willebrand factor.

It is assumed that pre-menopausal females have significantly higher estrogen levels than males.

Female levels decreased post-menopause.169

Alterations seen in women on hormone replacement therapy/ pregnancy / menstrual cycle.

Alterations seen with testosterone levels.170

Levels are non-significantly higher in men than age-matched post-menopausal women.

Female levels increased post-menopause more consistently than in men.157

Excluding women on hormone replacement therapy, pregnant, or during the puerperium.

Within the 46- to 64-year-old age group. Changes depending on race in the 65- to 74-year-old age group. No difference after 75 years.

Conclusion

The higher COVID-19 case fatality rate and increased severity of disease in males compared with females is likely due to a combination of behavioral/lifestyle risk factors, prevalence of co-morbidities, aging, and underlying biological sex differences. Several comorbidities, which disproportionally occur in men, likely contribute to worse COVID-19 outcomes, and concerns have been expressed whether ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers may exert adverse effects in COVID-19. Experimental and epidemiologic evidence is conflicting as to whether the use of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers upregulate ACE2 expression and impacts susceptibility to infection and/or disease severity. Randomized clinical trials in progress may inform recommendations about the use of such therapy in COVID-19 patients and whether this will differ by sex.

Based on the available literature, we conclude that biological sex differences may affect the pathogenic mechanisms of COVID-19, the risk for infection, and the severity of the disease, its outcomes, and its biomarkers. Indeed, experimental and epidemiologic evidence suggests that most of the biomarkers that have been tested in the context of the risk of infection and the severity of COVID-19 differ by sex at baseline within healthy populations. However, the role of biological sex and risk for infection and disease severity is complex and available data are not uniformly consistent. A notable example is that of the immune response: although females generally have an overall stronger immune response, males are more likely to develop the cytokine storm associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes. Further investigation into immunomodulation by sex hormones, age, and X-linked gene expression may help explain the worse survival of men, and may identify sex-specific risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection and the course, outcomes, and prognosis for COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joanna King, Creative Director of the Mayo Clinic Biomedical & Science Visualization Medical Illustration team, for her help in producing Figure 1. Drs Tu and Vermunt are first co-authors.

Footnotes

Potential Competing Interests: Dr Garovic has received grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL136348). The remaining authors report no competing interests.

Supplemental Online Material

References

- 1.Bhopal R. Covid-19 worldwide: we need precise data by age group and sex urgently. BMJ. 2020;369:m1366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Health 50/50. Sex, Gender and Covid-19. Vol 20202020: Sex, Gender and COVID-19. 2020. https://globalhealth5050.org/covid19/sex-disaggregated-data-tracker/

- 3.Dudley J.P., Lee N.T. Disparities in age-specific morbidity and mortality from SARS-CoV-2 in China and the Republic of Korea. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gebhard C., Regitz-Zagrosek V., Neuhauser H.K., Morgan R., Klein S.L. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11:29. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X., Fang J., Zhu Y. Clinical characteristics of non-critically ill patients with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in a Fangcang Hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(8):1063–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrilli C.M., Jones S.A., Yang J. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simonnet A., Chetboun M., Poissy J. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28(7):1195–1199. doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Rousan N., Al-Najjar H. Data analysis of coronavirus CoVID-19 epidemic in South Korea based on recovered and death cases. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China [in Chinese] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(2):145–151. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alkhouli M., Nanjundappa A., Annie F., Bates M.C., Bhatt D.L. Sex differences in COVID-19 case fatality rate: insights from a multinational registry. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(8):1613–1620. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin J.-M., Bai P., He W. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front Public Health. 2020;8:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng Y., Wu P., Lu W. Sex-specific clinical characteristics and prognosis of coronavirus disease-19 infection in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study of 168 severe patients. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(4):e1008520. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehra M.R., Desai S.S., Kuy S., Henry T.D., Patel A.N. Cardiovascular Disease, Drug Therapy, and Mortality in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;01:01. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Qin L., Li X., Shi J. Gendered effects on inflammation reaction and outcome of COVID-19 patients in Wuhan. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reitsma M.B., Fullman N., Ng M. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885–1906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2013;2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1015–1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bots S.H., Peters S.A.E., Woodward M. Sex differences in coronary heart disease and stroke mortality: a global assessment of the effect of ageing between 1980 and 2010. BMJ Global Health. 2017;2(2):e000298. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.GBD 2017 DALYs. HALE Collaborators Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1859–1922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32335-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y.Y., Liu D., Zhang P. Impact of ACE2 gene polymorphism on antihypertensive efficacy of ACE inhibitors. J Human Hypertens. 2016;30(12):766–771. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2016.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner A.J. In: The Protective Arm of the Renin Angiotensin System (RAS) Unger T., Steckelings U.M., dos Santos R.A.S., editors. Academic Press; Boston, MA: 2015. 25. ACE2 Cell Biology, Regulation, and Physiological Functions; pp. 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gheblawi M., Wang K., Viveiros A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. Circ Res. 2020;126(10):1456–1474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coutard B., Valle C., de Lamballerie X., Canard B., Seidah N.G., Decroly E. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antiviral Res. 2020;176:104742. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walls A.C., Park Y.-J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(2):281–292.e286. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santema B.T., Ouwerkerk W., Tromp J. Identifying optimal doses of heart failure medications in men compared with women: a prospective, observational, cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10205):1254–1263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31792-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tukiainen T., Villani A.-C., Yen A. Landscape of X chromosome inactivation across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550(7675):244–248. doi: 10.1038/nature24265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bukowska A., Spiller L., Wolke C. Protective regulation of the ACE2/ACE gene expression by estrogen in human atrial tissue from elderly men. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2017;242(14):1412–1423. doi: 10.1177/1535370217718808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hilliard L.M., Mirabito K.M., Widdop R.E., Denton K.M. In: The Protective Arm of the Renin Angiotensin System (RAS) Unger T., Steckelings U.M., dos Santos R.A.S., editors. Academic Press; Boston, Massachusetts: 2015. 17. Sex Differences in AT2R Expression and Action; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baughn L.B., Sharma N., Elhaik E., Sekulic A., Bryce A., Fonseca R. Targeting TMPRSS2 in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95 doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei X., Xiao Y., Wang J. Sex Differences in Severity and Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19: Evidence from Pooled Literature Analysis and Insights from Integrated Bioinformatic Analysis. https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.135472020 Pre-print. Accessed May 5, 2020.

- 36.Li M.Y., Li L., Zhang Y., Wang X.S. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai G. Bulk and single-cell transcriptomics identify tobacco-use disparity in lung gene expression of ACE2, the receptor of 2019-nCov. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.05.20020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leung J.M., Yang C.X., Tam A. ACE-2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: implications for COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):2000688. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00688-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chakladar J., Shende N., Li W.T., Rajasekaran M., Chang E.Y., Ongkeko W.M. Smoking-mediated upregulation of the androgen pathway leads to increased SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(10):3627. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lucas J.M., Heinlein C., Kim T. The androgen-regulated protease TMPRSS2 activates a proteolytic cascade involving components of the tumor microenvironment and promotes prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(11):1310–1325. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wambier C.G., Vaño-Galván S., McCoy J. Androgenetic alopecia present in the majority of hospitalized COVID-19 patients — the “Gabrin sign.”. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):680–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montopoli M., Zumerle S., Vettor R. Androgen-deprivation therapies for prostate cancer and risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2: a population-based study (N = 4532) Ann Oncol. 2020;31(8):1040–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asselta R., Mantovani A., Duga S. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 variants and expression as candidates to sex and country differences in COVID-19 severity in Italy. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.30.20047878. [Preprint.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng Z., Zhou J., To K.K. Identification of TMPRSS2 as a susceptibility gene for severe 2009 pandemic A(H1N1) influenza and A(H7N9) influenza. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(8):1214–1221. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeng F., Huang Y., Guo Y. Association of inflammatory markers with the severity of COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96(7):467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kermali M., Khalsa R.K., Pillai K., Ismail Z., Harky A. The role of biomarkers in diagnosis of COVID-19 — a systematic review. Life Sci. 2020;254:117788. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen G., Wu D., Guo W. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2620–2629. doi: 10.1172/JCI137244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brooks D.G., Trifilo M.J., Edelmann K.H., Teyton L., McGavern D.B., Oldstone M.B.A. Interleukin-10 determines viral clearance or persistence in vivo. Nat Med. 2006;12(11):1301–1309. doi: 10.1038/nm1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ejrnaes M., Filippi C.M., Martinic M.M. Resolution of a chronic viral infection after interleukin-10 receptor blockade. J Exp Med. 2006;203(11):2461–2472. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.di Mauro G., Cristina S., Concetta R., Francesco R., Annalisa C. SARS-Cov-2 infection: response of human immune system and possible implications for the rapid test and treatment. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;84:106519. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng F., Li L., Zeng J. Can we predict the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 with a routine blood test? Pol Arch Intern Med. 2020;130(5):400–406. doi: 10.20452/pamw.15331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang I., Pranata R. Lymphopenia in severe coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:36. doi: 10.1186/s40560-020-00453-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeng F., Dai C., Cai P. A comparison study of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody between male and female COVID-19 patients: a possible reason underlying different outcome between sex. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klein S.L., Flanagan K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(10):626–638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wikby A., Mansson I.A., Johansson B., Strindhall J., Nilsson S.E. The immune risk profile is associated with age and gender: findings from three Swedish population studies of individuals 20-100 years of age. Biogerontology. 2008;9(5):299–308. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Das B.R., Bhanushali A.A., Khadapkar R., Jeswani K.D., Bhavsar M., Dasgupta A. Reference ranges for lymphocyte subsets in adults from western India: influence of sex, age and method of enumeration. Indian J Med Sci. 2008;62(10):397–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Villacres M.C., Longmate J., Auge C., Diamond D.J. Predominant type 1 CMV-specific memory T-helper response in humans: evidence for gender differences in cytokine secretion. Hum Immunol. 2004;65(5):476–485. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taneja V. Sex hormones determine immune response. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1931. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Straub R.H. The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr Rev. 2007;28(5):521–574. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Borges do Nascimento I.J., Cacic N., Abdulazeem H.M. Novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in humans: a scoping review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):941. doi: 10.3390/jcm9040941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Y., Zhang Y., Zhao G. Difference in leukocyte composition between women before and after menopausal age, and distinct sexual dimorphism. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bain B.J., England J.M. Normal haematological values: sex difference in neutrophil count. Br Med J. 1975;1(5953):306–309. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5953.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu J., Liu Y., Xiang P. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts critical illness patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in the early stage. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02374-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yan X., Li F., Wang X. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as prognostic and predictive factor in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a retrospective cross-sectional study. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muller U., Steinhoff U., Reis L.F. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264(5167):1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robinson D.P., Lorenzo M.E., Jian W., Klein S.L. Elevated 17β-estradiol protects females from influenza A virus pathogenesis by suppressing inflammatory responses. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(7):e1002149. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scotland R.S., Stables M.J., Madalli S., Watson P., Gilroy D.W. Sex differences in resident immune cell phenotype underlie more efficient acute inflammatory responses in female mice. Blood. 2011;118(22):5918–5927. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-340281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Webb K., Peckham H., Radziszewska A. Sex and pubertal differences in the type 1 interferon pathway associate with both X chromosome number and serum sex hormone concentration. Front Immunol. 2019;9:3167. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berghofer B., Frommer T., Haley G., Fink L., Bein G., Hackstein H. TLR7 ligands induce higher IFN-alpha production in females. J Immunol. 2006;177(4):2088–2096. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Libert C., Dejager L., Pinheiro I. The X chromosome in immune functions: when a chromosome makes the difference. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(8):594–604. doi: 10.1038/nri2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang J., Syrett C.M., Kramer M.C., Basu A., Atchison M.L., Anguera M.C. Unusual maintenance of X chromosome inactivation predisposes female lymphocytes for increased expression from the inactive X. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(14):E2029–E2038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520113113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Narang K., Enninga E.A.L., Gunaratne M.D.S.K. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 during pregnancy: a multidisciplinary review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(8):1750–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garovic V.D., White W.M., Vaughan L. Incidence and long-term outcomes of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(18):2323–2334. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lippi G., Plebani M., Henry B.M. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang C., Shi L., Wang F.S. Liver injury in COVID-19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(5):428–430. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mendoza M., Garcia-Ruiz I., Maiz N. Pre-eclampsia-like syndrome induced by severe COVID-19: a prospective observational study. BJOG. 2020 doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gaskins A.J., Wilchesky M., Mumford S.L. Endogenous reproductive hormones and C-reactive protein across the menstrual cycle: the BioCycle study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(5):423–431. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Channappanavar R., Fett C., Mack M., Ten Eyck P.P., Meyerholz D.K., Perlman S. Sex-based differences in susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J Immunol. 2017;198(10):4046–4053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Medina K.L., Strasser A., Kincade P.W. Estrogen influences the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of early B-lineage precursors. Blood. 2000;95(6):2059–2067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Molloy E.J., O'Neill A.J., Grantham J.J. Sex-specific alterations in neutrophil apoptosis: the role of estradiol and progesterone. Blood. 2003;102(7):2653–2659. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Al-Lami R.A., Urban R.J., Volpi E., Algburi A.M.A., Baillargeon J. Sex hormones and novel corona virus infectious disease (COVID-19) Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(8):710–714. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu F., Li L., Xu M. Prognostic value of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin in patients with COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104370. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lippi G., Plebani M. Procalcitonin in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;505:190–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zheng Z., Peng F., Xu B. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81(2):e16–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Taylor R., Jones A., Kelly S., Simpson M., Mabey J. A review of the value of procalcitonin as a marker of infection. Cureus. 2017;9(4):e1148. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tang H., Huang T., Jing J., Shen H., Cui W. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment in patients with infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection. 2009;37(6):497–507. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-9034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barassi A., Pallotti F., d’Eril G.M. Biological variation of procalcitonin in healthy individuals. Clin Chem. 2004;50(10):1878. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.037275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rondanelli M., Miccono A., Lamburghini S. Self-care for common colds: the pivotal role of vitamin D, vitamin C, ainc, and echinacea in three main immune interactive clusters (physical barriers, innate and adaptive immunity) involved during an episode of common colds—practical advice on dosages and on the time to take these nutrients/botanicals in order to prevent or treat common colds. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:5813095. doi: 10.1155/2018/5813095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Autier P., Mullie P., Macacu A. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on non-skeletal disorders: a systematic review of meta-analyses and randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(12):986–1004. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mitchell F. Vitamin-D and COVID-19: do deficient risk a poorer outcome? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(7):570. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30183-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martineau A.R., Jolliffe D.A., Hooper R.L. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhou Y.-F., Luo B.-A., Qin L.-L. The association between vitamin D deficiency and community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98(38):e17252. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Orwoll E., Nielson C.M., Marshall L.M. Vitamin D deficiency in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(4):1214–1222. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Laird E., Rhodes J., Kenny R.A. Vitamin D and inflammation: potential implications for severity of COVID-19. Ir Med J. 2020;113(5):81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ilie P.C., Stefanescu S., Smith L. The role of vitamin D in the prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 infection and mortality. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.D'Avolio A., Avataneo V., Manca A. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are lower in patients with positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2. Nutrients. 2020;12(5):1359. doi: 10.3390/nu12051359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hastie C.E., Mackay D.F., Ho F. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bonow R.O., Fonarow G.C., O’Gara P.T., Yancy C.W. Association of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with myocardial injury and mortality. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hu H., Ma F., Wei X., Fang Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis saved with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. Eur Heart J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Inciardi R.M., Adamo M., Lupi L. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and cardiac disease in Northern Italy. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(19):1821–1829. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Santoso A., Pranata R., Wibowo A., Al-Farabi M.J., Huang I., Antariksa B. Cardiac injury is associated with mortality and critically ill pneumonia in COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li J.W., Han T.W., Woodward M. The impact of 2019 novel coronavirus on heart injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lippi G., Lavie C.J., Sanchis-Gomar F. Cardiac troponin I in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence from a meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(3):390–391. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Han H., Xie L., Liu R. Analysis of heart injury laboratory parameters in 273 COVID-19 patients in one hospital in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):819–823. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gao L., Jiang D., Wen X.S. Prognostic value of NT-proBNP in patients with severe COVID-19. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01352-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wei J.F., Huang F.Y., Xiong T.Y. Acute myocardial injury is common in patients with covid-19 and impairs their prognosis. Heart. 2020;106(15):1154–1159. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Omland T., de Lemos J.A., Holmen O.L. Impact of sex on the prognostic value of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I in the general population: the HUNT study. Clin Chem. 2015;61(4):646–656. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.234369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lew J., Sanghavi M., Ayers C.R. Sex-based differences in cardiometabolic biomarkers. Circulation. 2017;135(6):544–555. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wiviott S.D., Cannon C.P., Morrow D.A. Differential expression of cardiac biomarkers by gender in patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a TACTICS-TIMI 18 (Treat Angina with Aggrastat and determine Cost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conservative Strategy-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 18) substudy. Circulation. 2004;109(5):580–586. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109491.66226.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Daniels L.B., Maisel A.S. Cardiovascular biomarkers and sex: the case for women. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(10):588–596. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chang A.Y., Abdullah S.M., Jain T. Associations among androgens, estrogens, and natriuretic peptides in young women: observations from the Dallas Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(1):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lei F., Liu Y.M., Zhou F. Longitudinal association between markers of liver injury and mortality in COVID-19 in China. Hepatology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hep.31301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Phipps M.M., Barraza L.H., LaSota E.D. Acute liver injury in COVID-19: prevalence and association with clinical outcomes in a large US cohort. Hepatology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hep.31404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ceriotti F., Henny J., Queralto J. Common reference intervals for aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) in serum: results from an IFCC multicenter study. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2010;48(11):1593–1601. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2010.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Prati D., Taioli E., Zanella A. Updated definitions of healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(1):1–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-1-200207020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mera J.R., Dickson B., Feldman M. Influence of gender on the ratio of serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in patients with and without hyperbilirubinemia. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(3):799–802. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9924-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Chen C.H., Huang M.H., Yang J.C. Prevalence and etiology of elevated serum alanine aminotransferase level in an adult population in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(9):1482–1489. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Fadini G.P., de Kreutzenberg S., Albiero M. Gender differences in endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular risk profile: the role of female estrogens. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(5):997–1004. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Feitosa M.F., Reiner A.P., Wojczynski M.K. Sex-influenced association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2013;227(2):420–424. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hirsch J.S., Ng J.H., Ross D.W. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;98(1):209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Pei G., Zhang Z., Peng J. Renal involvement and early prognosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(6):1157–1165. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Cheng Y., Luo R., Wang K. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97(5):829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ronco C., Reis T., Husain-Syed F. Management of acute kidney injury in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(7):738–742. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Neugarten J., Silbiger S.R. Effects of sex hormones on mesangial cells. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26(1):147–151. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Neugarten J., Golestaneh L. Influence of sex on the progression of chronic kidney disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(7):1339–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Columbia University Kidney Transplant Program Early description of coronavirus 2019 disease in kidney transplant recipients in New York. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(6):1150–1156. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Alberici F., Delbarba E., Manenti C. A single center observational study of the clinical characteristics and short-term outcome of 20 kidney transplant patients admitted for SARS-CoV2 pneumonia. Kidney Int. 2020;97(6):1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Husain S.A., Dube G., Morris H. Early outcomes of outpatient management of kidney transplant recipients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(8):1174–1178. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05170420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pereira M.R., Mohan S., Cohen D.J. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: Initial report from the US epicenter. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(7):1800–1808. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lodigiani C., Iapichino G., Carenzo L. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Helms J., Tacquard C., Severac F. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Henry B.M., de Oliveira M.H.S., Benoit S., Plebani M., Lippi G. Hematologic, biochemical and immune biomarker abnormalities associated with severe illness and mortality in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(7):1021–1028. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lv Z., Cheng S., Le J. Clinical characteristics and co-infections of 354 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Microbes Infect. 2020;22(4-5):195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Yang X., Yang Q., Wang Y. Thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1469–1472. doi: 10.1111/jth.14848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Liu Y., Sun W., Guo Y. Association between platelet parameters and mortality in coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective cohort study. Platelets. 2020;31(4):490–496. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2020.1754383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Varga Z., Flammer A.J., Steiger P. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Luo W., Yu H., Gou J. Clinical pathology of critical patient with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) Preprints. 2020:2020020407. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Spiezia L., Boscolo A., Poletto F. COVID-19-related severe hypercoagulability in patients admitted to intensive care unit for acute respiratory failure. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(6):998–1000. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Panigada M., Bottino N., Tagliabue P. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit. A report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/jth.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zátroch I., Smudla A., Babik B. Procoagulation, hypercoagulation and fibrinolytic “shut down” detected with ClotPro® viscoelastic tests in COVID-19 patients. [In Hu.] Orv Hetil. 2020;161(22):899–907. doi: 10.1556/650.2020.31870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Viguier A., Delamarre L., Duplantier J., Olivot J.M., Bonneville F. Acute ischemic stroke complicating common carotid artery thrombosis during a severe COVID-19 infection. J Neuroradiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kashi M., Jacquin A., Dakhil B. Severe arterial thrombosis associated with Covid-19 infection. Thromb Res. 2020;192:75–77. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Bhatti A.F., Leon L.R., Labropoulos N. Free-floating thrombus of the carotid artery: Literature review and case reports. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(1):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Cui S., Chen S., Li X., Liu S., Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Santimone I., Di Castelnuovo A., De Curtis A. White blood cell count, sex and age are major determinants of heterogeneity of platelet indices in an adult general population: results from the MOLI-SANI project. Haematologica. 2011;96(8):1180–1188. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.043042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Jayachandran M., Miller V.M. Human platelets contain estrogen receptor alpha, caveolin-1 and estrogen receptor associated proteins. Platelets. 2003;14(2):75–81. doi: 10.1080/0953710031000080562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hodges Y.K., Tung L., Yan X.D., Graham J.D., Horwitz K.B., Horwitz L.D. Estrogen receptors alpha and beta: prevalence of estrogen receptor beta mRNA in human vascular smooth muscle and transcriptional effects. Circulation. 2000;101(15):1792–1798. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.15.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Mendelsohn M.E., Karas R.H. The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1801–1811. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Best P.J., Berger P.B., Miller V.M., Lerman A. The effect of estrogen replacement therapy on plasma nitric oxide and endothelin-1 levels in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(4):285–288. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-4-199802150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Florian M., Lu Y., Angle M., Magder S. Estrogen induced changes in Akt-dependent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and vasodilation. Steroids. 2004;69(10):637–645. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Lawrence J.B., Leifer D.W., Moura G.L. Sex Differences in Platelet Adherence to Subendothelium: Relationship to Platelet Function Tests and Hematologic Variables. Am Med J Sci. 1995;309(4):201–207. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199504000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Lowe G.D., Rumley A., Woodward M. Epidemiology of coagulation factors, inhibitors and activation markers: the Third Glasgow MONICA Survey. I. Illustrative reference ranges by age, sex and hormone use. Br J Haematol. 1997;97(4):775–784. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.1222936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Conlan M.G., Folsom A.R., Finch A. Associations of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor with age, race, sex, and risk factors for atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70(3):380–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]