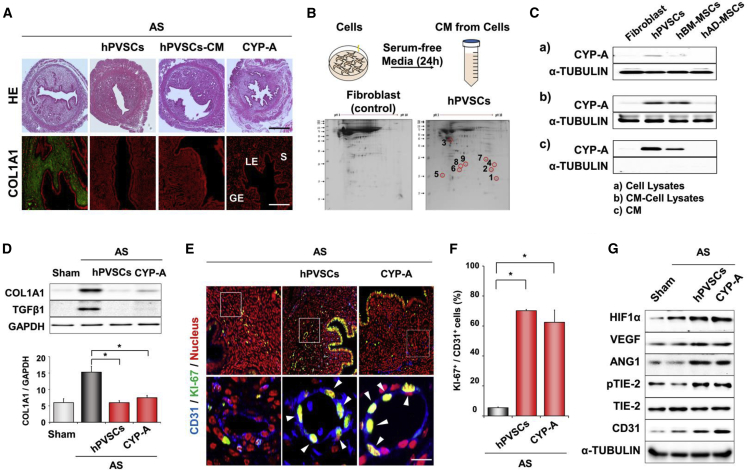

Figure 6.

CYP-A Secreted from hPVSCs Contributes Major Therapeutic Actions of hPVSCs on Uterine Restoration in Mice with AS

(A) Gross histology (H&E) and IF staining for COL1A1 in uterine sections of mice with AS after intrauterine delivery of hPVSCs, concentrated conditioned medium (CM) of hPVSCs, and CYP-A. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) A schematic diagram and gel images of 2D electrophoresis of experiments with CM from hPVSCs and human lung fibroblasts. CM was harvested after being incubated with cells in a serum-starved condition for 24 h. CM from hPVSCs had several unique spots compared to CM of lung fibroblasts (numbers 1 to 9). (C) Western blotting for CYP-A in cells incubated under serum-contained (a) and -starved conditions (b), respectively, and CM (c) of (b). Note that CYP-A is predominantly secreted from hPVSCs among MSCs tested. (D) Representative images of western blotting and graphs for COL1A1 and TGF-β1 protein in mice with AS after CYP-A treatment (n = 4 or 5 mice in each group). ∗p < 0.05. (E) coIF staining for CD31 and KI-67 in mice with AS after CYP-A treatment. Blue, green, and red colors indicate CD31, KI-67, and nucleus, respectively. White arrows indicate KI-67 positive nuclei (yellow color) in endothelial cells. Scale bar, 25 μm. (F) Graphs depicting the percentage of KI-67 positive cells/CD31 positive cells counted. ∗p < 0.05. (G) Western blotting for HIF1α, VEGF-A, ANG1, TIE-2, pTIE-2, and CD31 in mice with AS after CYP-A treatment. Note that CYP-A treatment itself significantly increases the expression of all angiogenesis-related factors tested in mice with AS (n = 6–8 mice in each group). Green and red colors indicate COL1A1 and nucleus, respectively in (A) and (D). LE, luminal epithelial cells; GE, glandular epithelial cells; S, stromal cells.