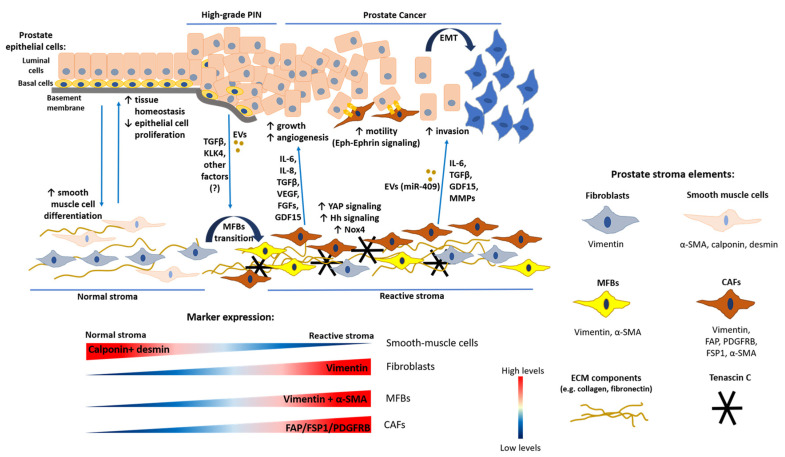

Figure 1.

Tumor–stroma interactions in primary prostate cancer (PCa) progression. Simplified representation of the epithelial and stromal components and their interactions during primary PCa tumorigenesis (blood vessels and immune cells are not reported). In normal conditions, the epithelium is highly organized with the basement membrane separating basal and luminal cells from the underlying stroma. The main cellular components of the stroma are fibroblasts (expressing vimentin) and smooth muscle cells (expressing α-SMA, calponin and desmin). Epithelial-stromal cell interaction maintains tissue homeostasis, smooth-muscle cell differentiation and inhibits epithelial cell proliferation. Tumor-initiating events (e.g., epithelial cell genetic alterations, chronic inflammation) increase luminal cell proliferation, potentially leading to the development of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). In this condition, the stroma is characterized by low smooth muscle cells and the presence of myofibroblasts (MFBs) (co-expressing vimentin and α-SMA). Epithelial cells release TGFβ ligands, Kallikrein-related peptidase-4 (KLK4), extracellular vesicles (EVs) and possibly other factors, inducing normal fibroblast transition into MFBs, increased extracellular matrix (ECM) component deposition (e.g., collagen, fibronectin) and TNC secretion, typical characteristics of reactive stroma. Disruption of the basal cell layer leads to PCa and is a pre-requisite for tumor cell invasiveness. In primary PCa, fibroblasts and MFBs acquire pro-tumorigenic properties, thus being defined as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (which are a heterogenous cellular population expressing several markers such as FAP, PDGFRB, FSP-1, and α-SMA). Due to the change in the cellular composition of reactive stroma, the immunohistochemistry of primary PCa tissue samples is typically characterized by lower calponin and desmin expression, increased vimentin staining (due to the high number of fibroblasts, especially CAFs) and co-localization of vimentin and α-SMA (indicating MFBs and CAFs). CAFs establish a paracrine communication with cancer cells through the release of factors such as IL-6, IL-8, TGFβ, FGFs, VEGF, and GDF15, stimulating tumor growth, angiogenesis, and progression. Moreover, they activate YAP and Hedgehog (Hh) signaling and express NADPH-oxidase 4 (Nox4), which induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Direct CAF–cancer cell contact enhances cancer cell motility through Eph-Ephrin signaling. Eventually, CAFs promote tumor invasion by inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), e.g., through the release of factors such as matrix-metalloproteinases (MMPs) or EVs containing microRNA-409 (miR-409), potentially leading to metastasis.