Abstract

This article investigates a family of approximate solutions for the fractional model (in the Liouville-Caputo sense) of the Ebola virus via an accurate numerical procedure (Chebyshev spectral collocation method). We reduce the proposed epidemiological model to a system of algebraic equations with the help of the properties of the Chebyshev polynomials of the third kind. Some theorems about the convergence analysis and the existence-uniqueness solution are stated. Finally, some numerical simulations are presented for different values of the fractional-order and the other parameters involved in the coefficients. We also note that we can apply the proposed method to solve other models.

Keywords: Fractional derivatives, Ebola virus, Epidemiological model, Corona virus, Chebyshev polynomials of the third-kind, Chebyshev spectral collocation method, Newton-Raphson method

MSC: 34A08, 35A22, 41A30, 65N22

1. Introduction, definitions and preliminaries

Fractional calculus has kept attracting the interest of many authors (see, for example, [5] and [6]). Some authors have observed that finding new fractional derivatives with different singular or non-singular kernels is essential to meet the need for modeling more real-world problems in different fields, such as biology, physics, engineering and others (see [14] and [39]).

Recently, the focus of many researchers is directed toward the modeling and analysis of various problems in bio-mathematical sciences. This branch of science represents many and distinct data about the biological phenomena such as the Ebola virus, the Bacterial cell and its distribution, Viruses, Nerve system and the transmission of its impulses, and so on (see [2], [11] and [30]). This has led to the modeling of many real-world issues including (for example) the aforementioned ones. Most (if not all) of these mathematical models that arise from many real-life problems are proposed and studied on the basis of biological experiences or statistical analysis. It is through some of these models that the interested scientist can studied and verify the behavior of these models in isolation in a modern laboratory-type biology experiment (see [3], [8], [20], [24] and [31]).

One of the advantages of mathematical modeling of various biological phenomena is that the mathematical model is represented as a mathematical function in time and the involved parameters. Hence, in this case, we can find the exact solutions to the model and also the parameters that affect this model can be controlled appropriately (see [17], [18], [19], [20]).

We begin by introducing the following definition which will be needed in our fractional-order epidemiological model of the Ebola virus.

Definition 1

The Liouville-Caputo derivative operator Dν of fractional-order ν is defined in the following form (see [23] and [28]; see also the recent survey-cum-expository review article [35]):

Here, in this article, we present a numerical study to solve the following fractional-order epidemiological model of the Ebola virus [9]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where ν ∈ (0, 1]. In the above system, the main variables and coefficients are defined in the following table.

| Symbol | definition | Symbol | definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| The susceptible population | The rate of infection with the disease | ||

| The infected population | The rate of susceptibility | ||

| The recovery population | The rate of natural death | ||

| The population died in the region | The rate of death from the disease | ||

| The total population in the region | The rate of recovery from the disease | ||

The Ebola virus disease (EVD) was discovered in the Democratic Republic of the Congo near the Ebola River (Africa) for the first time in 1976. It is a fatal disease with a rare outbreak (see, for details, [30]). The EDV infects people from time to time and causes disease outbreaks in some African countries due to the impact of the Ebola virus disease on humans and primates (such as monkeys, gorillas and chimpanzees). It is difficult for many biologists to determine the exact origin of the virus. However, by its comparison with and similarity to the nature and behavior of the Ebola virus with other viruses, it has been found that it is mostly transmitted from animals. Bats or non-human primates are believed to be the origin and source of the Ebola virus (see, for example, [4] and [26]). The transmission and infection of monkeys from animals that carry the virus and from monkeys it is then transmitted to humans and non-human primates. Generally speaking, the Ebola virus can infect humans in one of the following ways: Direct contact with humans, blood, body fluids, animal tissues, and through direct contact with body fluids of a sick person or a person who died from the Ebola virus disease. As the current onslaught of the Corona virus, which is referred to as COVID-19 (see, for details, [1], [27] and [29]), the Ebola virus is transmitted to other patients or the virus can pass through broken skin or mucous membranes in the eyes, nose and mouth when a person comes into contact with infected body fluids (or contaminated objects), but the Ebola virus is also transmitted through sexual contact with someone who has the virus or who has recovered from it (see [7]; see also the recently-published works [36] and [37] for the fractional-order modeling of other diseases).

In a recent investigation, Dokuyucu and Dutta [9] demonstrated the existence of the solution for the EVD model (1), (2), (3), (4) with the help of some fixed-point theorems and by using the Liouville-Caputo fractional derivative. In addition, they showed the uniqueness of the solution of this system under some specified initial conditions. Combined solutions for S(t), I(t), R(t) and D(t) can be found in [10] and [13].

The Chebyshev polynomials are a well-known family of orthogonal polynomials on the interval that have many applications. They are widely used because of their good properties in the approximation of functions. So the main aim of this study is to implement the Chebyshev spectral collocation method (CSCM) in order to solve the EVD model given by (1) to (4) and to show that CSCM greatly simplifies this model to a non-linear system of algebraic equations which becomes solvable by using any of the readily available numerical methods and techniques. In order to achieve this aim, we will use some advantages of the CSCM for solving this class of models in which the Chebyshev coefficients for the solution can exist very easily after using the numerical programs. For this reason, this method is much faster than the other methods. Also, this method provides a numerical technique with high accuracy, exponential rates of convergence and easy to use in finite and infinite domains for different problems (see [21], [32] and [33]).

The main structure of this paper is as follows. In Section 2, the numerical scheme and its convergence analysis are presented. In Section 3, the implementation the proposed method and numerical simulation are given. In Section 4, the numerical results and discussion are introduced. Finally, in Section 5, the conclusion is presented.

2. Numerical scheme and its convergence analysis

The classical orthogonal Chebyshev polynomials of the third kind and of degree n, which are orthogonal on can be derived from the following formula (see, for example, [25] and [34]):

In this section, we will use these functions on [0, ℏ], so we can construct the so-called shifted Chebyshev polynomials by using the linear transform . This type of functions is denoted and defined as follows:

where

One of the most useful formulas involving is the analytic form given by (Khader [15], Khader and Babatin [16]):

The function Ω(t) ∈ L 2[0, ℏ] can be approximated as a finite sum of as follows:

| (5) |

Theorem 1

Khader and Saad [22]

Suppose that the function Ω(t) is so constrained that Ω″(t) ∈ L 2[0, ℏ] and where ξ is a constant. Then the series (5) of the shifted Chebyshev expansion is uniformly convergent and:

(6)

Theorem 2

Khader and Saad [22] Suppose that Ω(t) ∈ Cm[0, 1]. Then the error in approximating the function Ω(t) by Ωm(t) by using the formula (5) can be bounded by:

(7)

In this section, we also give an approximate formula for DνΩm(t) through the following theorem.

Theorem 3

( [12], [38] ) Suppose that the function Ω(t) is approximated in the form (5). Then Dν(Ωm(t)) can be defined by:

(8)

3. Implementation the proposed method and numerical simulation

We will now implement the Chebyshev spectral collocation method to solve numerically the EVD model in (1), (2), (3), (4) as follows:

| (9) |

By using (1), (2), (3), (4), (9) and the formula (8), we obtain:

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

These last (10), (11), (12), (13) will be collocated at m nodes as follows:

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

In addition, the associated initial conditions can be expressed by substituting from Eq. (9) therein. We are thus led to the following four equations:

| (18) |

Finally, (14), (15), (16), (17), together with the four equations in (18), give rise to a non-linear system of algebraic equations. This system of algebraic equations will be solved for the following unknowns: by using the Newton-Raphson iteration method (NIM).

4. Numerical results and discussion

In this section, we solve the EVD model numerically by implementing the given method and demonstrate our solution by means of Figures 1–6. We consider Eqs. (1) to (4) with different values of ν, m, α, β, γ, δ, ϵ, N, and ℏ, as well as and

In Fig. 1 , we compare the approximate solutions (9) and the numerical solution based on the finite difference method by using the program Mathematica for the specific value . The other parameters are taken as and . The initial values, and are used here.

Fig. 1.

Graph of the comparison between the approximate solutions (9) and the numerical solutions at and . (Solid color: Approximate solutions; Dashed color: Numerical solutions). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

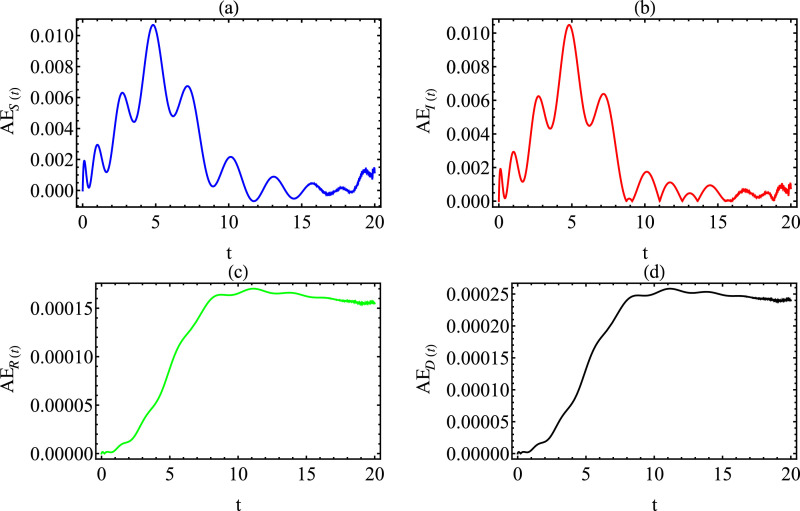

In Fig. 2 , we show the absolute error between the approximate solutions (9) and the numerical solution for the same parameters as in Fig. 1, but for . From these two figures (Figs. 1 and (2), we can observe that the approximate solutions are very much in agreement with the corresponding numerical solutions. The comparisons are made with the integer-order derivative. In fact, we also show satisfaction with the effective and accuracy of the results involving derivative of non-integer order. Since most of the models do not have the exact solutions and also most of the similar programs are usually not capable of generating numerical solutions, so we need to verify the accuracy of the results by using some procedure. We can check the accuracy of the results by defining the residual error function (REf) as follows:

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

Fig. 2.

Graph of the absolute error function of (9) with and .

Now, in view of the CSCM, the REf is given by:

| (23) |

| (24) |

| (25) |

| (26) |

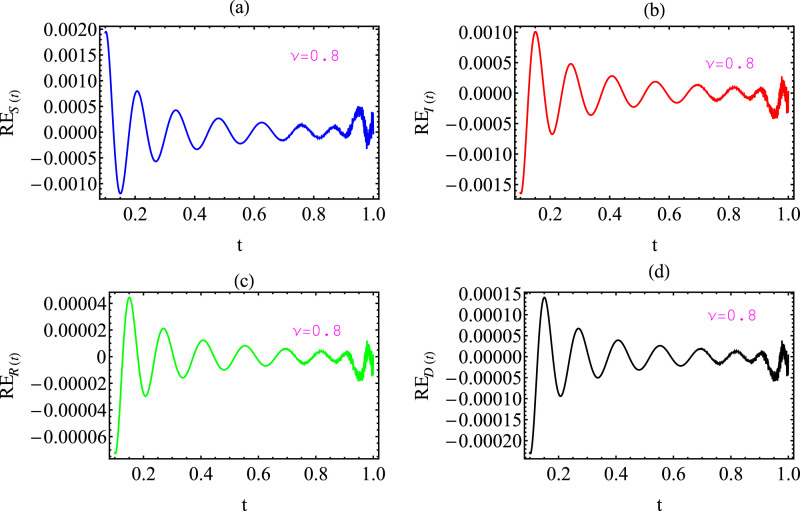

For computing the REf, we set and ; with in Fig. 3 and in Fig. 4 . The initial conditions in these two figures are taken to be and From the previous two figures (Figs. 3 and 4, we find that the results obtained in the fractional-order case indicate the accuracy and validity of the results presented in this work. In this way, we can verify the accuracy of the solutions in the case of a fractional order in which there is no exact solution.

Fig. 3.

Graph of the residual error function (23), (24), (25), (26) with and with and .

Fig. 4.

Graph of the absolute error function of (9) and (17) with and with and

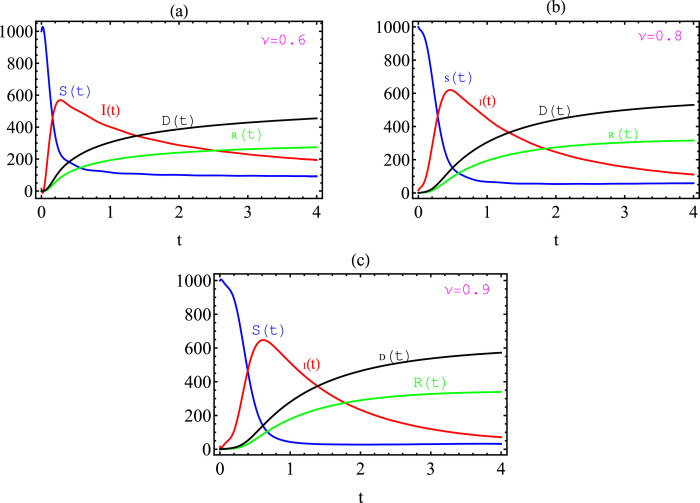

Next, in Figs. 5 and 6 , the behavior of the approximate solutions are studied with various specific values of the parameters as well as for different values of fractional-order. In Fig. 5, we take for the values ; and with initial values given by and While in Fig. 6, we put for the values ; and with the initial values given by and Thus, from these Figs. 5 and 6, we note that the behavior of the approximate solutions is dependent strongly on the values of ν and the other chosen parameters.

Fig. 5.

Graph of the approximate solutions (9) with for the values

Fig. 6.

Graph of the approximate solutions (9) with for the values and .

Finally, from all the figures which we present in this paper, we can confirm the efficiency of the proposed algorithm and its computationally favorable use for numerical treatment of the given model. We can also observe that all of the theoretical studies, which are concerned with the convergence analysis, are accomplished. In addition, the main and important note is that the behavior of the numerical solutions is in excellent agreement with the real meaning of the model and satisfies the same behavior of the components of the system S(t), I(t), R(t), D(t) via the increasing or decreasing numbers of each of these variables.

5. Conclusion

In our present investigation, we have proposed and applied a numerical method in order to successfully convert the fractional epidemiological model of the Ebola virus into a non-linear system of algebraic equations. The idea is to find expansions of the solutions by using the Chebyshev functions of the third kind. We then have made use of one of the known numerical methods, the Newton-Raphson method, for solving the resulting non-linear algebraic system. The accuracy of the approximate solutions was verified for our usage of the proposed method by closely comparing the approximate solutions with the numerical solutions resulting by using the computer program package Mathematica. In the case of the classical Ebola system (that is, in the case when ), as well as in the case of its fractional-order model, the residual error function is calculated. In all of the cases, we have found a remarkably good agreement. Finally, the behavior of the fractional epidemiological Ebola system was illustrated by assigning different values to the order of the fractional derivative as well as for different values of the other parameters involved. Several numerical simulations and illustrative graphical demonstrations have also been presented in this investigation. The applied techniques in this article show that their effect and power can be extended to other fractional-order models and the non-linear evolutions equations.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

H.M. Srivastava: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Khaled M. Saad: Writing - original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Software. M.M. Khader: Writing - original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Software.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Abdo M.S., Shah K., Wahash H.A., Panchal S.K. On a comprehensive model of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) under mittag-leffler derivative. Chaos Solitons. 2020:109867. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amundsen S.B. Historical analysis of the ebola virus: prospective implications for primary care nursing today. Clin Excell Nurse Pract. 1998;2:343–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Area I., Batarfi H., Losada J., Nieto J.J., Shammakh W., Torres A. On a fractional order ebola epidemic model. Adv Differ Equ. 2015;2015:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Area I., Ndairou F., Nieto J.J., Silva C.J. Ebola model and optimal control with vaccination constraints. J Industr Manage Optim. 2018;14:427–446. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baleanu D., Jajarmi A., Mohammad H., Rezapour S. A new study on the mathematical modelling of human liver with caputo-fabrizio fractional derivative. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2020;134:109705. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baleanu D., Jajarmi A., Sajjadi S.S., Asad J. The fractional features of a harmonic oscillator with position-dependent mass. Commun Theor Phys. 2020;72(5):055002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baseler L., Chertow D.S., Johnson K.M., Feldmann H., Morens D.M. The pathogenesis of ebola virus disease. Ann Rev Pathol. 2017;12:387–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-052016-100506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonyah E., Badu K., Asiedu-Addo S.K. Optimal control application to an ebola model. Asian-Pacific J Trop Biomed. 2016;6:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtb.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dokuyucu M.A., Dutta H. A fractional order model for ebola virus with the new caputo fractional derivative without singular kernel. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2020;134:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durojaye M.O., Ajie I.J. Mathematical model of the spread and control of ebola virus disease. Appl Math. 2017;7:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emond R.T., Evans B., Bowen E.T., Lloyd G. A case of ebola virus infection. British Med J. 1977;2:541–544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6086.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handan C.Y. Numerical solution of fractional riccati differential equation via shifted chebyshev polynomials of the third kind. J Engrg Technol Appl Sci. 2017;28:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hossain M.T., Miah M.M., Hossain M.B. Numerical study of kermack-mckendrik SIR model to predict the outbreak of ebola virus diseases using euler and fourth order runge-kutta methods. Amer Sci Res J Engrg Technol Sci. 2017;37:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jajarmi A., Yusuf A., Baleanu D., Inc M. A new fractional HRSV model and its optimal control: a nonsingular operator approach. Physica A: Statist Mech Appl. 2020;547:123860. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khader M.M. On the numerical solutions for the fractional diffusion equation. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2011;16:2535–2542. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khader M.M., Babatin M.M. Numerical treatment for solving fractional SIRC model and influenza a. Comput Appl Math. 2014;33:543–556. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khader M.M. The numerical solution for BVP of the liquid film flow over an unsteady stretching sheet with thermal radiation and magnetic field using FEM. Internat J Modern Phys C. 2019;15(3):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khader M.M., Adel M. Introducing the windowed fourier frames technique for obtaining the approximate solution of coupled system of differential equations. J Pseudo-Differ Oper Appl. 2019;10:241–256. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khader M.M., Adel M. Chebyshev wavelet procedure for solving FLDEs. Acta Appl Math. 2018;158(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khader M.M., Saad K.M. Numerical treatment for studying the blood ethanol concentration systems with different forms of fractional derivatives. Internat J Modern Phys C. 2020;31(3):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khader M.M., Saad K.M. A numerical study using chebyshev collocation method for a problem of biological invasion: fractional fisher equation. Internat J Biomath. 2018;11(8):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khader M.M., Saad K.M. A numerical approach for solving the problem of biological invasion (fractional fisher equation) using chebyshev spectral collocation method. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2018;110:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilbas A.A., Srivastava H.M., Trujillo J.J. North-Holland mathematical studies. vol. 204. Elsevier (North-Holland) Science Publishers; Amsterdam, London and New York: 2006. Theory and applications of fractional differential equations. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koca I. Modelling the spread of ebola virus with atangana-baleanu fractional operators. Eur Phys J Plus. 2018;133(3):100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mason J.C., Handscomb D.C. Chapman and Hall (CRC Press); New York and Boca Raton: 2003. Chebyshev polynomials. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazandu G.K., Nembaware V., Thomford N.E., Bope C., Ly O., Chimusa E.R. A potential roadmap to overcome the current eastern DRC ebola virus disease outbreak: from a computational perspective. Sci Afr. 2020;7:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ndairou F., Area I., Nieto J.J., Torres D.F.M. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 transmission dynamics with a case study of wuhan. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2020;135:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fractional differential equations: An introduction to fractional derivatives. Fractional Differential Equations, to Methods of Their Solution and Some of Their Applications, Mathematics in Science and Engineering, 98, Academic Press, New York, London, Sydney, Tokyo and Toronto 1999.

- 29.Postnikov E.B. Estimation of COVID-19 dynamics “on a back-of-envelope”: does the simplest SIR model provide quantitative parameters and predictions?, Chaos Solitons Fract. 2020;135:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rachah A., Torres D.F.M. Mathematical modelling, simulation, and optimal control of the 2014 ebola outbreak in west africa. Discr Dyn Nature Soc. 2015;3:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rachah A., Torres D.F.M. Predicting and controlling the ebola infection. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2017;40:6155–6164. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saad K.M., Srivastava H.M., Gómez-Aguilar J.F. A fractional quadratic autocatalysis associated with chemical clock reactions involving linear inhibition. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2020;132:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh H., Srivastava H.M. Jacobi collocation method for the approximate solution of some fractional-order riccati differential equations with variable coefficients. Physica A: Statist Mech Appl. 2019;523:1130–1149. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snyder M.A. Prentice-Hall Incorporated; Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: 1966. Chebyshev methods in numerical approximation. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Srivastava H.M. Fractional-order derivatives and integrals: introductory overview and recent developments. Kyungpook Math J. 2020;60:73–116. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srivastava H.M., Dubey R.S., Jain M. A study of the fractional-order mathematical model of diabetes and its resulting complications. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2019;42:4570–4583. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srivastava H.M., Günerhan H. Analytical and approximate solutions of fractional-order susceptible-infected-recovered epidemic model of childhood disease. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2019;42:935–941. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sweilam N.H., Nagy A.M., El-Sayed A.A. On the numerical solution of space fractional order diffusion equation via shifted chebyshev polynomials of the third kind. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2016;28:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yildiz T.A., Jajarmi A., Yildiz B., Baleanu D. New aspects of time fractional optimal control problems within operators with nonsingular kernel. Discr Cont Dyna Syst-S. 2020;13(3):407–428. [Google Scholar]