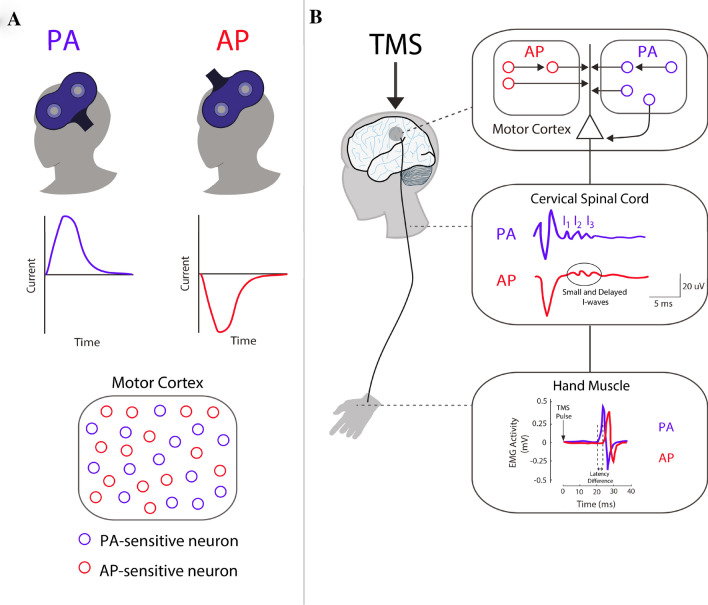

Fig. 1.

Key differences between PA- and AP-TMS applied to the brain. a Diagram depicting the location and position of the TMS coil over the primary motor cortex (M1). Monophasic posterior-to-anterior (PA) and anterior-to-posterior (AP) pulse waveforms are capable of recruiting different subsets of M1 neurons. b Stimulation with a figure-of-eight coil over M1 can produce twitches of a desired muscle, which are quantified using electromyography to record the resulting motor-evoked potential (MEP). The descending activity of this complex signal can also be revealed by recording directly from the surface of the spinal cord. This is possible with patients that have electrodes implanted at the high cervical level (~ C2). When a pulse is given with a lateral–medial current (not shown), recordings at the cervical spinal reveal a D-wave, which reflects direct activation of the pyramidal tract. This is followed by a series of indirect waves (I1, I2, and I3) produced from intracortical neurons that are mono- and poly-synaptically connected to pyramidal neurons. Importantly, stimulation with PA currents predominately recruits the I1 wave and is capable of recruiting late I-waves at higher intensities. On the other hand, AP currents produce smaller volleys that are delayed relative to those recruited by PA currents. This is realized when recording the onset of motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) due to brain stimulation. PA currents have been found to consistently evoke faster MEP response when compared to MEPs induced with AP currents (~ 2–3 ms difference). Of note, the responses of AP currents both between and within participants can vary substantially with standard TMS pulse durations