Abstract

Findings regarding the moderating influence of drinking motives on the association between affect and alcohol consumption have been inconsistent. The current study extended previous work on this topic by examining episode-specific coping, enhancement, conformity, and social drinking motives as moderators of the association between daytime experiences of positive and negative affect and evening social and solitary alcohol consumption. Nine hundred and six participants completed daily diary surveys measuring their daily affect and evening drinking behavior each day for 30 days during college and again 5 years later, after they had left the college environment. Results of multilevel modeling analyses suggest that the associations between affect, drinking motives, and alcohol consumption are not straightforward. Specifically, whereas daytime positive affect and non-coping drinking motives predicted greater social consumption, daytime positive affect was related to lower solitary alcohol consumption among college students who were low in state social drinking motives. In addition, coping motives were related to greater social consumption during college and greater solitary alcohol consumption after college. Future research should continue to examine these episode-specific drinking motives in addition to trait-level drinking motives.

Keywords: drinking motives, affect, social drinking, solitary drinking, college students, young adults

1. Introduction

The motivational model of alcohol use proposes that alcohol is used to regulate positive and negative affect and that these links might depend on motivational and contextual factors (Cooper et al., 2016; Cox & Klinger, 1988). Both negative affect (Bilevicius et al., 2018) and drinking to cope (Cooper et al., 2016) are more strongly related to solitary drinking and alcohol-related consequences than positive affect and approach-oriented motives. Positive affect (Dvorak et al., 2016), enhancement (Gautreau et al., 2015), and social motivation (Williams & Clark, 1998) are more strongly related to overall consumption. There is less consistent evidence that motivational processes moderate the affect-drinking association (see Armeli et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2009; Hussong et al., 2005; Rousseau et al., 2011), i.e., negative affect should be more closely linked to alcohol use in instances when it is consumed as a coping strategy. These inconsistencies might be due to the focus on examining differences in trait-level drinking motives as potential moderators. The current study explores how state-like components of drinking motives moderate the associations between affect and alcohol consumption alone and with others.

1.1. Affect and Drinking Motives

Cooper (1994) proposed that drinking motives be categorized based on their source (internal/external) and valence (positive/negative), creating four motives: coping (internal/negative), conformity (external/negative), enhancement (internal/positive), and social (external/positive). This four-factor structure has been validated in diverse samples and motives have been linked to drinking in specific situations and following unique patterns (Cooper et al., 2016). Research testing motives as moderators of the daily affect-drinking association has used micro-longitudinal methods (e.g., daily diary; experience sampling) with motives examined at the person-level but has not come to a consensus. Specifically, some studies show negative affect associated with greater consumption for individuals who characteristically drink to cope (Grant et al., 2009; Rousseau et al., 2011) whereas others do not (Armeli et al., 2010; Hussong et al., 2005). Regarding trait-level drinking to enhance motives, Gautreau et al. (2015) did find that daily positive affect was associated with greater consumption.

These inconsistencies might be because even when reporting a high level of one motive, an individual may not be drinking for that reason on a specific occasion to alter specific affective states. Daily experiences influence evening reports of drinking motives (Arbeau et al., 2011; Ehrenberg et al., 2016) and drinking motives have both trait and state components (O’Hara et al., 2015). Recent research examining these state-level drinking motives, suggests that within-person analyses may provide unique insights into motive-consumption associations. For example, O’Donnell and colleagues (2019) found that enhancement motivation predicted drinking initiation at the within-person daily level, but not at the between-person level. In addition, Stevenson and colleagues’ (2019) daily study of college students showed that coping motives predict consequences at the between person level, but not at the daily level. There is further evidence suggesting that within-person coping motives may mediate the effects of negative mood on alcohol consumption (Dvorak et al., 2014), but this is not always found (see Stevenson et al., 2019). These conflicting findings for motives across level of analysis and the weak evidence that affect is related to drinking behavior indirectly through motives raises the possibility that affect and motives may affect drinking synergistically and that this moderating effect on the affect-drinking association might also differ across level of analysis. Specifically, we expect that there should be a stronger correlation between negative affect and drinking during episodes when individuals are drinking to cope. Similarly, there should be a stronger correlation between positive affect and drinking during episodes when individuals are drinking to enhance.

1.2. Drinking Context

The motivational model of alcohol consumption’s source dimension (internal/external; Cooper, 1994) suggests social context (i.e., drinking alone versus with others) may play a role in the affect-alcohol association. A meta-analysis suggests that solitary drinking is particularly important to study as a potential risk factor for alcohol related problems (Skrzynski & Creswell, 2020). Further, drinking to cope with negative affect may be more strongly related to solitary (versus social) alcohol consumption. Less research has examined the moderating role of drinking motives on social versus solitary consumption. Mohr and colleagues (2005) examined trait-level drinking motives as moderators of the association between daily mood and alcohol consumption at home and away from home. Participants who drank at home spent less time with others and those who drank away from home spent substantial time with friends (i.e., drinking away from home was mostly social while drinking at home was often solitary). They found that trait-level drinking to cope, conform, and enhance moderated the effects of positive and negative affect on drinking at home. In particular, greater negative mood predicted drinking at home for individuals who endorsed drinking to cope while lower positive mood predicted drinking at home for individuals who endorsed enhancement motives. The current study furthers this research by testing whether state-level motives moderate the positive association between daily affect and social and solitary alcohol consumption.

Another contextual factor to consider is whether participants are currently in college. College students are within the developmental phase of emerging adulthood where substance abuse peaks as students are no longer monitored by parents but have not yet taken on adult roles (Arnett, 2000). It is important to consider whether affect and drinking motives have similar associations with alcohol consumption during versus after college. The current study examines these associations among undergraduate students during college and five years later when they have left the college environment.

1.3. Current Research

The current study extends past research on the associations among affective states, drinking motives, and alcohol consumption by examining these affective, motivational and behavioral factors for drinking episodes over time. Most important, we examined episode-specific (rather than between-person) levels of drinking motives as moderators of the association between daytime affect and evening alcohol consumption, extending past research examining daily motives as mediators between mood and consumption. Using daily diary methodology, we examined whether episode-specific drinking motives moderated the effects of positive and negative affect on social and solitary alcohol consumption. During drinking episodes characterized by relatively higher levels of drinking to cope, we expected a positive association between daytime negative affect and social and solitary alcohol consumption. During drinking episodes characterized by relatively higher levels of social and/or enhancement motivation, we expected positive affect to be associated with greater social alcohol consumption but less solitary alcohol consumption. We did not expect coping motives to moderate the effects of positive affect or social/enhancement motives to moderate the effects of negative affect. We made no hypotheses regarding conformity motives, which are the least strongly endorsed and show inconsistent relations with drinking (Cooper et al., 2016)1

We also examined these daily processes across two important time points during young adulthood: college years and approximately five years later. We made no predictions for these exploratory analyses. By examining whether these patterns change as students make the transition out of emerging adulthood (see Arnett, 2000), we have the potential to increase understanding of drinking motives and developmental changes in affect regulation.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants included 906 individuals recruited as undergraduate students at the University of Connecticut who, both as college students and again 5 years later, completed an initial survey and at least 15 days of a 30-day daily diary study. To be eligible for Wave 2 (post-college), participants must have reported at least one heavy drinking day (i.e., ≥ 4 drinks for women and ≥ 5 drinks for men) in both the initial and daily surveys during Wave 1 (college).2 These moderate to heavy drinkers were chosen because of their increased potential for risky alcohol use following graduation (Beseler et al., 2012; Campbell & Demb, 2008). Individuals who participated in both waves had an average age of 19.18 years (SD=1.26) at Wave 1 and 24.56 years (SD=1.33) at Wave 2. About half were women (54%). They completed an average of 26.33 (SD=3.68) diary surveys in Wave 1 and 27.92 (SD=3.33) diary surveys in Wave 2.3

2.2. Procedure

The University of Connecticut and UConn Health institutional review boards approved all procedures. For Wave 1, undergraduate students were recruited via the psychology participant pool and campus-wide emails, provided informed consent, and agreed to be contacted for subsequent studies. Participants completed an initial online survey assessing demographic information, then completed an online daily diary survey each day for 30 days between 2:30pm and 7:00pm (time window selected to coincide with undergraduate students’ naturally occurring end of school day before typical evening activities begin). For Wave 2, participants provided informed consent, completed an initial online survey, and then completed the same online daily diary survey each day for 30 days between 4:00pm and 8:30pm (time window selected to coincide with the end of the workday before typical evening activities begin).

2.3. Measures4

2.3.1. Daytime Affect

In each daily survey, participants reported the extent to which 18 adjectives described how they felt that day on a 5-point scale (1=not at all, 5=extremely). Adjectives were selected from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded (Watson et al., 1988) and Larsen and Diener’s (1992) mood circumplex. Ten items (e.g. sad, hostile) were averaged to form a measure of negative affect (α=.77). Eight items (e.g., happy, excited) were averaged to form a measure of positive affect (α=.82).

2.3.2. Evening Alcohol Consumption

In each daily survey, participants indicated how many alcoholic beverages they had consumed alone (i.e., solitary drinks) and with others (i.e., social drinks) the previous evening. Participants were reminded that a standard drink is one 12-oz beer or wine cooler, one 5-oz glass of wine, or a 1-oz measure of liquor straight or in a mixed drink.5

2.3.3. Evening Drinking Motives

On evenings when participants reported drinking, they were asked to report whether each of 11 items described why they drank that night on a 3-point scale (0=no, 1=somewhat, 2=definitely; adapted from Cooper, 1994). Evening drinking to cope was the average of five items (i.e., “to feel more confident,” “to forget ongoing problems/worries,” “to feel less depressed,” “to feel less nervous,” “to cheer up”; α=.78). Evening drinking to conform was the average of two items (i.e., “because my friends pressured me,” “to fit in with a group I like”; rs=.55 Evening social motive was the average of two items (i.e., “to make a party/gathering more fun,” “to improve a party/gathering”; rs=.88 Evening enhancement motive was the average of two items (i.e., “because I like the pleasant feeling,” “to have fun”; rs=.63).

2.4. Analysis Plan

Because days (Level 1) were nested within participants (Level 2) and the outcome variable (number of drinks consumed) is a count variable, we conducted generalized estimating equations (GEE) with a Poisson distribution and a log-link function using SPSS. Level 1 predictor variables were person-centered (i.e., each participant’s mean across the 30 days was subtracted from daily levels), product terms were calculated from centered variables, and between-subjects means were entered allowing us to disentangle within-versus between-persons associations (Kenny et al., 1998; Nezlek, 2001). Therefore, a participants’ coefficient for positive affect describes the relation between changes from that person’s average report of positive affect and alcohol consumption. We also calculated exponentiated slopes (exp[b]); these values represent the rate of change in the mean level of outcome for a unit change in the predictor. We controlled for age, gender, race, and number of diary surveys completed. Because we predicted evening drinking (reported the next day) from daytime affect, participants had to have consecutive days of data (i.e., skipping one day resulted in losing two days of data). Significant interactions were examined using the procedures outlined by Aiken and West (1991). Binary variables were coded as follows: Wave (time 1 = −.5, time 2 = .5), Gender (male = −.5 = male, female =.5) and Race (White = −.5, non-White = .5). To probe significant interactions, we used +/−1 SD to represent high and low levels for the moderator.

3. Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and correlations for between-persons and aggregate daily variables separately for each wave. Generalized estimating equations were conducted to test whether episode-specific drinking motives moderate the influence of daytime affect on evening alcohol consumption and whether these associations differed between waves. Separate analyses were conducted for social versus solitary alcohol consumption.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Between-Person and Aggregate Daily Variables

| Measure | M | SD | N | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Number of days completed | 26.33 (27.92) | 3.68 (3.33) | 906 (906) | .07* | .04 | .04 | .08* | .06 | .01 | .06 | .01 | .003 | −.11** | .01 | |

| 2. Gender | 906 (906) | 14** | – | −.03 | −.06 | .10** | −.002 | −.03 | −.09** | .01 | −.11** | −.27** | −.21** | ||

| 3. Race | 906 (906) | .04 | −.02 | – | −.03 | .10** | .08* | −.03 | −.02 | .04 | .01 | .15** | .01 | ||

| 4. Age | 19.18 (24.56) | 1.26 (1.33) | 906 (906) | .01 | −.07* | −.03 | – | −.02 | −.002 | −.06 | −.01 | −.07* | −.09** | .05 | .05 |

| 5. Positive affect | 2.63 (2.35) | 0.60 (0.39) | 906 (906) | .07* | .05 | .12** | −.08* | – | .81** | −.07* | .001 | .18** | .07* | .01 | −.07* |

| 6. Negative affect | 1.50 (2.02) | 0.40 (0.31) | 906 (906) | −.07* | .13** | −.05 | −.02 | −.08* | – | .17** | .09** | .16** | .08* | .000 | −.04 |

| 7. Coping motives | 0.26 (0.12) | 0.33 (0.20) | 891 (870) | −.02 | .09** | −.04 | −.05 | −.14** | .57** | – | .53** | .24** | .30** | .05 | .15** |

| 8. Conformity motives | 0.16 (0.11) | 0.27 (0/20) | 891 (870) | .03 | .001 | −.02 | −.07* | −.01 | .36** | .55** | – | .16** | .38** | .04 | .06 |

| 9. Enhancement motives | 1.28 (0.91) | 0.48 (0.48) | 891 (870) | .01 | .03 | .05 | −.08* | .13** | .08** | .28** | .12** | – | .59** | 23** | .03 |

| 10. Social motives | 1.15 (0.66) | 0.55 (0.45) | 891 (870) | .03 | .01 | .05 | −.13** | .08* | .10** | .35** | .30** | .65** | – | .22** | −.05 |

| 11. Number of social drinks | 1.32 (1.12) | 1.16 (0.93) | 906 (906) | −.19** | −.33** | 14** | .12** | .01 | −.06 | −.02 | .03 | 14** | .21** | – | .24** |

| 12. Number of solitary drinks | 0.12 (0.12) | 0.31 (0.28) | 906 (906) | −.13** | −.18** | .01 | 14** | −.03 | .11* | .06 | .06 | −.09** | −.07* | .29** | – |

Note: Wave 2 M, SD, and N in parentheses. Correlations below the diagonal are Wave 1; above the diagonal are Wave 2. Gender was coded −1 = male, 1 = female; thus, positive correlations denote higher values for women relative to men. Race was coded −1 = non-White, 1 = White; thus, positive correlations denote higher values for White participants relative to others.

p < .05;

p < .01

3.1. Social Alcohol Consumption

Analyses examining number of drinks consumed with others revealed that social drinking was greater among younger, male, White participants (see Table 2).6 At mean levels of all other variables, greater than average levels of positive affect during the day were related to greater social consumption that night and, on drinking-episodes when participants reported greater than average conformity motives, they reported greater social consumption. The effects of coping, enhancement, and social motives and of Wave are qualified by significant interactions.

Table 2.

Drinks Consumed Alone and with Others as a Function of Daytime Affect and Episode-Specific Drinking Motives

| Variable | b | SE | Exp (B) | 95% CI for Exp (B) | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of drinks consumed with others | ||||||

| Gender | −0.30 | 0.02 | 0.74 | 0.72, 0.77 | 213.73 | <.001 |

| Age | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 0.96, 0.99 | 7.87 | .01 |

| Race | 0.13 | 0.03 | 1.13 | 1.07, 1.21 | 15.35 | <.001 |

| Wave | −0.16 | 0.05 | 0.86 | 0.77, 0.95 | 8.77 | .003 |

| Average positive affect | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.94 | 0.91, 0.98 | 8.47 | .004 |

| Average negative affect | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 0.89, 1.01 | 3.09 | .08 |

| Average coping motives | −0.16 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 0.78, 0.93 | 13.19 | <.001 |

| Average conformity motives | 0.11 | 0.05 | 1.12 | 1.02, 1.23 | 5.41 | .02 |

| Average enhancement motives | 0.17 | 0.03 | 1.19 | 1.12, 1.26 | 34.48 | <.001 |

| Average social motives | 0.35 | 0.03 | 1.41 | 1.33, 1.50 | 128.63 | <.001 |

| Positive affect | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.04 | 1.01, 1.07 | 8.73 | .003 |

| Negative affect | 0.004 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.97, 1.04 | 0.03 | .85 |

| Coping motives | 0.07 | 0.02 | 1.08 | 1.02, 1.13 | 8.17 | .004 |

| Conformity motives | 0.15 | 0.01 | 1.16 | 1.11, 1.21 | 42.67 | <.001 |

| Enhancement motives | 0.34 | 0.02 | 1.40 | 1.36, 1.45 | 429.67 | <.001 |

| Social motives | 0.43 | 0.01 | 1.54 | 1.50, 1.58 | 1015.63 | <.001 |

| Positive affect × Wave | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.94, 1.04 | 0.29 | .59 |

| Negative affect × Wave | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.91, 1.06 | 0.16 | .69 |

| Coping motives × Wave | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.81, 1.00 | 4.10 | .04 |

| Conformity motives × Wave | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.91, 1.09 | 0.02 | .90 |

| Enhancement motives × Wave | 0.08 | 0.03 | 1.08 | 1.02, 1.15 | 7.29 | .01 |

| Social motives × Wave | 0.08 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 1.03, 1.14 | 10.28 | .001 |

| Coping motives × Positive affect | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.88, 1.07 | 0.38 | .54 |

| Conformity motives × Positive affect | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.83, 1.01 | 3.15 | .08 |

| Enhancement motives × Positive affect | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1.01 | 0.96, 1.08 | 0.20 | .66 |

| Social motives × Positive affect | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.97 | 0.92, 1.02 | 1.15 | .28 |

| Coping motives × Negative affect | −0.001 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.88, 1.13 | 0.00 | .99 |

| Conformity motives × Negative affect | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.99 | 0.87, 1.12 | 0.05 | .82 |

| Enhancement motives × Negative affect | 0.02 | 0.05 | 1.02 | 0.92, 1.14 | 0.21 | .65 |

| Social motives × Negative affect | 0.002 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.93, 1.08 | 0.003 | .96 |

| Coping motives × Positive affect × Wave | −0.03 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.80, 1.18 | 0.09 | .76 |

| Conformity motives × Positive affect × Wave | −0.11 | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0.73, 1.11 | 0.97 | .32 |

| Enhancement motives × Positive affect × Wave | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.09 | 0.97, 1.23 | 1.99 | .16 |

| Social motives × Positive affect × Wave | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.94 | 0.85, 1.04 | 1.51 | .22 |

| Coping motives × Negative affect × Wave | 0.20 | 0.13 | 1.23 | 0.96, 1.57 | 2.60 | .11 |

| Conformity motives × Negative affect × Wave | −0.004 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.77, 1.30 | 0.001 | .98 |

| Enhancement motives × Negative affect × Wave | −0.12 | 0.09 | 0.89 | 0.74, 1.07 | 1.58 | .21 |

| Social motives × Negative affect × Wave | 0.05 | 0.08 | 1.05 | 0.91, 1.22 | 0.41 | .52 |

| Number of drinks consumed alone | ||||||

| Gender | −0.86 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.35, 0.51 | 80.85 | <.001 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.04 | 1.02 | 0.95, 1.09 | 0.22 | .64 |

| Race | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.99 | 0.74, 1.34 | 0.002 | .97 |

| Wave | −0.42 | 0.25 | 0.66 | 0.40, 1.07 | 2.85 | .09 |

| Average positive affect | −0.12 | 0.12 | 0.89 | 0.71, 1.12 | 0.97 | .33 |

| Average negative affect | −0.13 | 0.17 | 0.88 | 0.63, 1.22 | 0.63 | .43 |

| Average coping | 0.97 | 0.24 | 2.65 | 1.66, 4.22 | 16.67 | <.001 |

| motives | ||||||

| Average conformity motives | 0.35 | 0.37 | 1.42 | 0.69, 2.92 | 0.89 | .35 |

| Average enhancement motives | −0.01 | 0.14 | 0.99 | 0.76, 1.29 | 0.01 | .94 |

| Average social motives | −0.48 | 0.16 | 0.62 | 0.46, 0.84 | 9.35 | .002 |

| Positive affect | 0.13 | 0.07 | 1.14 | 0.99, 1.32 | 3.38 | .07 |

| Negative affect | 0.002 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.85, 1.19 | 0.001 | .98 |

| Coping motives | 0.77 | 0.14 | 2.16 | 1.65, 2.83 | 31.48 | <.001 |

| Conformity motives | −0.08 | 0.14 | 0.93 | 0.71, 1.21 | 0.31 | .58 |

| Enhancement motives | 0.06 | 0.08 | 1.06 | 0.90, 1.24 | 0.46 | .50 |

| Social motives | −0.51 | 0.08 | 0.60 | 0.51, 0.70 | 40.07 | <.001 |

| Positive affect × Wave | −0.08 | 0.13 | 0.92 | 0.72, 1.19 | 0.36 | .55 |

| Negative affect × Wave | −0.11 | 0.17 | 0.90 | 0.65, 1.24 | 0.42 | .52 |

| Coping motives × Wave | 0.71 | 0.24 | 2.04 | 1.26, 3.30 | 8.50 | .004 |

| Conformity motives × Wave | −0.23 | 0.29 | 0.79 | 0.45, 1.39 | 0.66 | .42 |

| Enhancement motives × Wave | −0.09 | 0.16 | 0.91 | 0.66, 1.26 | 0.30 | .59 |

| Social motives × Wave | −0.61 | 0.15 | 0.54 | 0.41, 0.73 | 17.17 | <.001 |

| Coping motives × Positive affect | 0.20 | 0.25 | 1.23 | 0.76, 1.99 | 0.68 | .41 |

| Conformity motives × Positive affect | −0.02 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.56, 1.70 | 0.01 | .93 |

| Enhancement motives × Positive affect | −0.12 | 0.23 | 0.89 | 0.69, 1.15 | 0.78 | .38 |

| Social motives × Positive affect | 0.26 | 0.13 | 1.30 | 1.00, 1.69 | 3.91 | .05 |

| Coping motives × Negative affect | −0.57 | 0.29 | 0.56 | 0.32, 1.00 | 3.82 | .05 |

| Conformity motives × Negative affect | −0.05 | 0.37 | 0.95 | 0.46, 1.94 | 0.02 | .89 |

| Enhancement motives × Negative affect | 0.40 | 0.26 | 1.50 | 0.91, 2.47 | 2.49 | .11 |

| Social motives × Negative affect | 0.002 | 0.22 | 1.00 | 0.65, 1.54 | 0.00 | .99 |

| Coping motives × Positive affect × Wave | 0.67 | 0.48 | 1.96 | 0.76, 5.06 | 1.94 | .16 |

| Conformity motives × Positive affect × Wave | 0.44 | 0.52 | 1.56 | 0.56, 4.31 | 0.73 | .39 |

| Enhancement motives × Positive affect × Wave | 0.38 | 0.30 | 1.47 | 0.82, 2.64 | 1.65 | .20 |

| Social motives × Positive affect × Wave | −0.74 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.27, 0.86 | 6.11 | .01 |

| Coping motives × Negative affect × Wave | −0.75 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.15, 1.50 | 1.63 | .20 |

| Conformity motives × Negative affect × Wave | 0.81 | 0.78 | 2.24 | 0.48, 10.42 | 1.06 | .30 |

| Enhancement motives × Negative affect × Wave | −0.16 | 0.47 | 0.85 | 0.34, 2.12 | 0.12 | .73 |

| Social motives × Negative affect × Wave | −0.12 | 0.45 | 0.89 | 0.37, 2.14 | 0.07 | .79 |

Note. Wave is coded −.5 = Wave 1, .5 = Wave 2. Gender is coded −.5 = male, .5 = female. Race is coded −.5 = non-White, .5 = White.

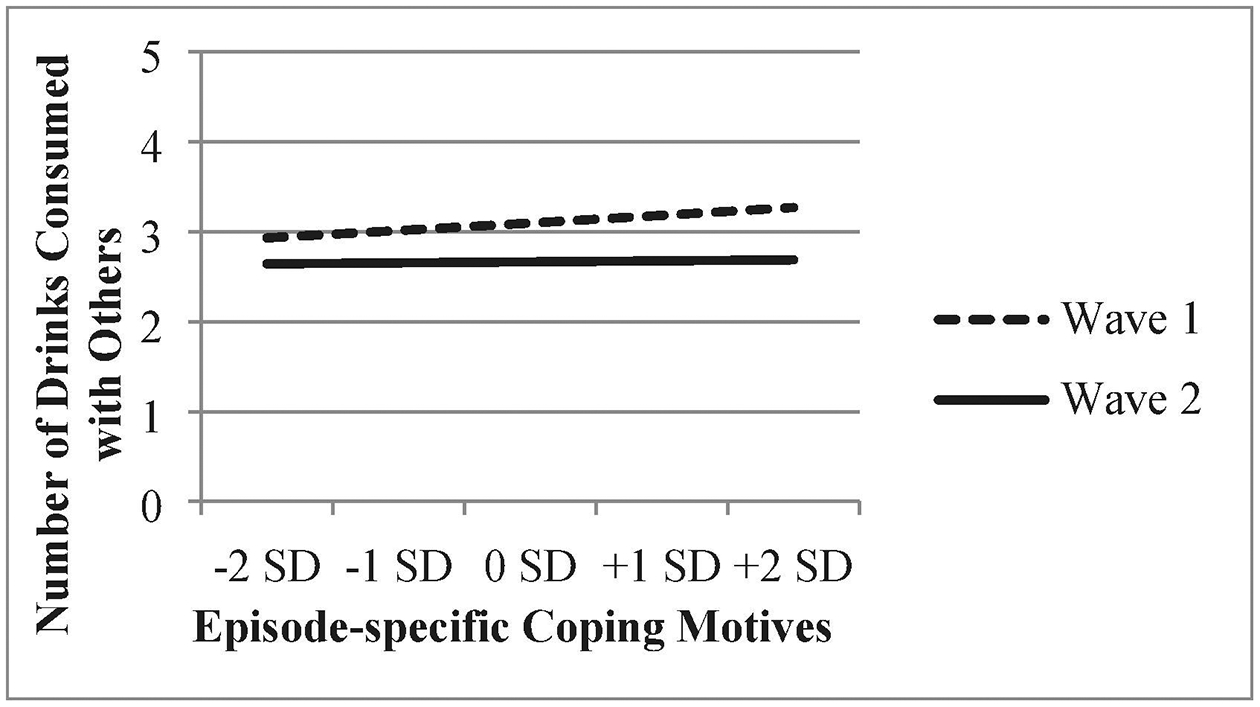

Probing of the significant Coping motives × Wave interaction revealed a significant positive effect of coping motives on social drinking during Wave 1, b=0.13, SE=0.03, Exp(B)=1.13, χ2(1, N=12128)=15.48, p<.001 (see Figure 1). In contrast, there was no effect of coping motives on social drinking during Wave 2, b=0.02, SE=0.04, Exp(B)=1.02, χ2(1, N=12128)=0.28, p=.60. Participants consumed more alcohol with others on evenings when they reported that they were drinking to cope during college, but not after college.

Figure 1.

Number of Drinks Consumed with Others as a Function of Episode-Specific Coping Motives and Wave

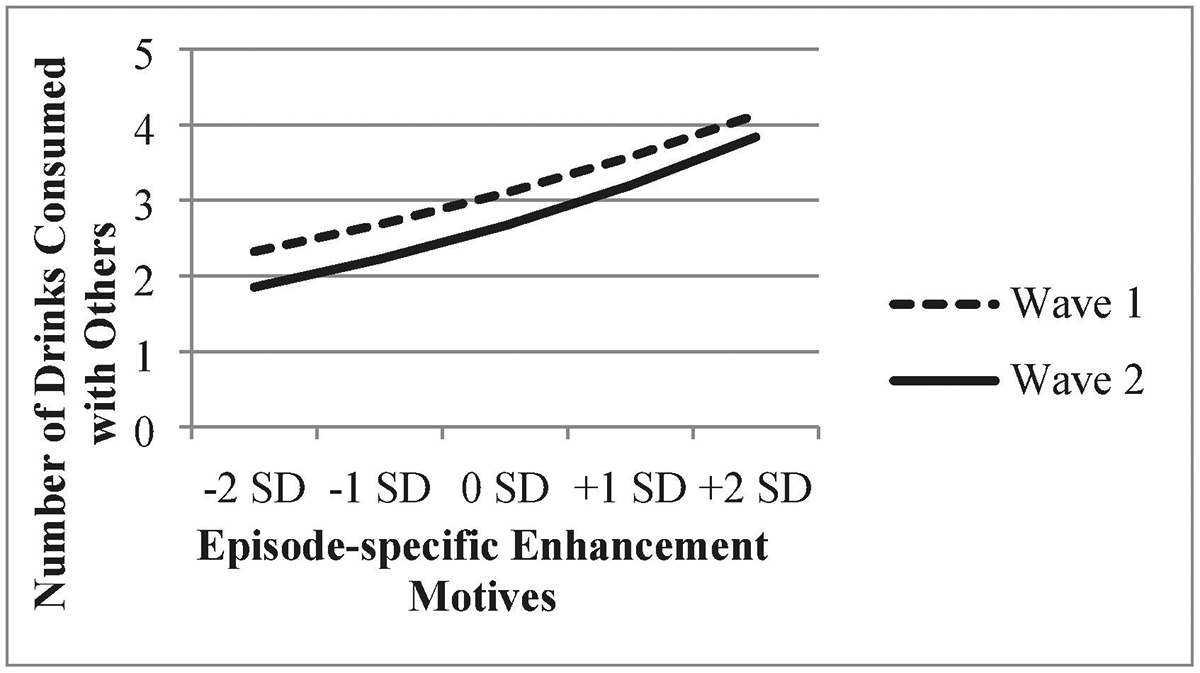

Probing of the significant Enhancement motives × Wave interaction revealed a significant effect of Enhancement motives on social drinking during Wave 1, b=0.30, SE=0.02, Exp(B)=1.35, χ2(1, N=12128)=153.99, p<.001 (see Figure 2). However, this effect was stronger during Wave 2, b=0.38, SE=0.02, Exp(B)=1.46, χ2(1, N=12128)=357.09, p<.001. Participants consumed more alcohol with others on evenings when they reported that they were drinking to enhance, and this effect was stronger after college (versus during).

Figure 2.

Number of Drinks Consumed with Others as a Function of Episode-Specific Enhancement Motives and Wave

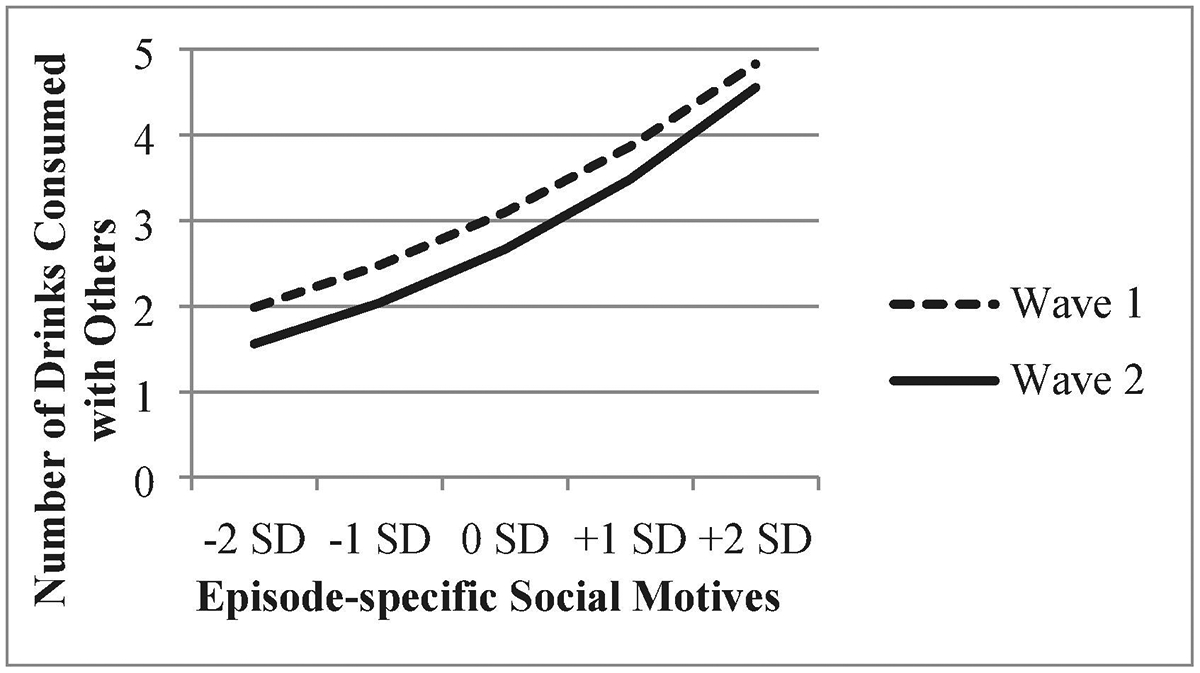

Probing of the significant Social motives × Wave interaction revealed a significant effect of Social motives on social drinking during Wave 1, b=0.39, SE=0.02, Exp(B)=1.48, χ2(1, N=12128)=347.17, p<.001 (see Figure 3). However, this effect was stronger during Wave 2, b=0.47, SE=0.02, Exp(B)=1.60, χ2(1, N=12128)=849.09, p<.001. Participants consumed more alcohol with others on evenings when they reported that they were drinking for social motives, and this effect was stronger after college (versus during).

Figure 3.

Number of Drinks Consumed with Others as a Function of Episode-Specific Social Motives and Wave

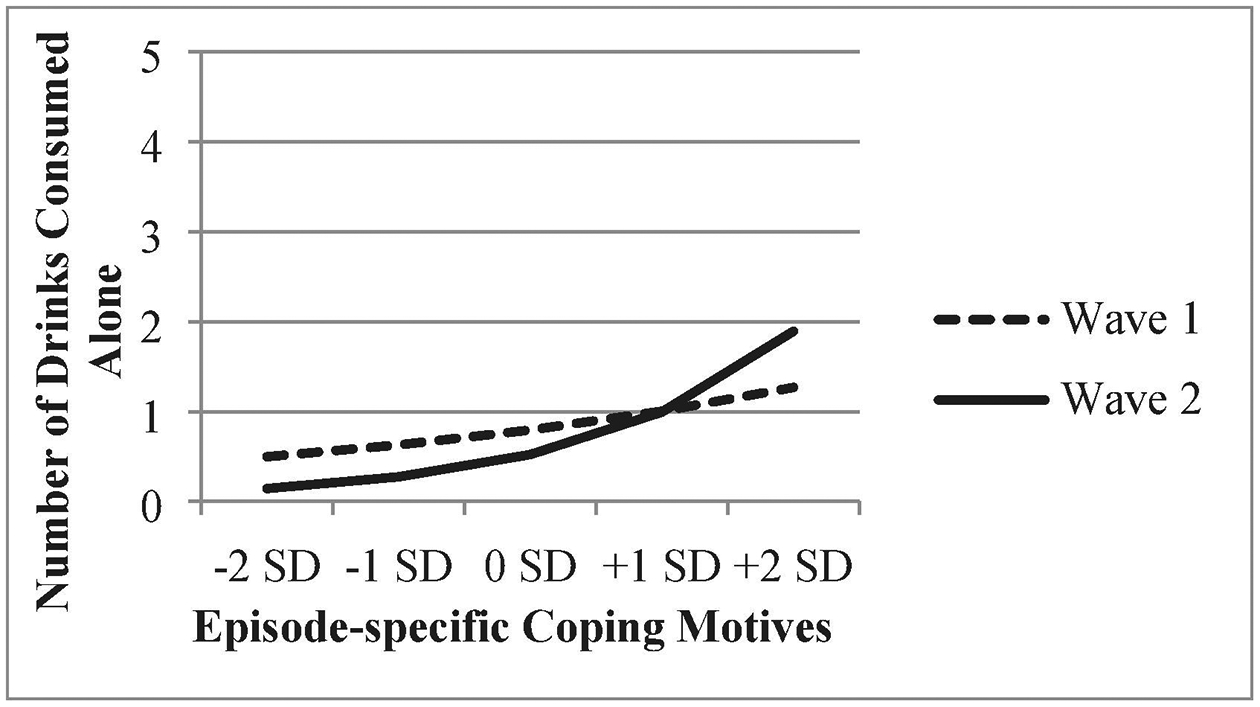

3.2. Solitary Alcohol Consumption

Analyses examining number of drinks consumed alone revealed that men drank more than women at mean levels of affect and all motives (see Table 2). Significant effects of coping motives and social motives are qualified by significant interactions. Probing of the significant Coping motives × Wave interaction revealed no significant effect of coping motives on solitary drinking during Wave 1, b=0.41, SE=0.21, Exp(B)=1.51, χ2(1, N=12128)=3.75, p=.05 (see Figure 4). In contrast, there was a significant positive effect during Wave 2, b=1.13, SE=0.15, Exp(B)=3.08, χ2(1, N=12128)=56.82, p<.001. This suggests that drinking to cope is only related to greater solitary alcohol consumption after participants are no longer in the college environment.

Figure 4.

Number of Drinks Consumed Alone as a Function of Episode-Specific Coping Motives and Wave

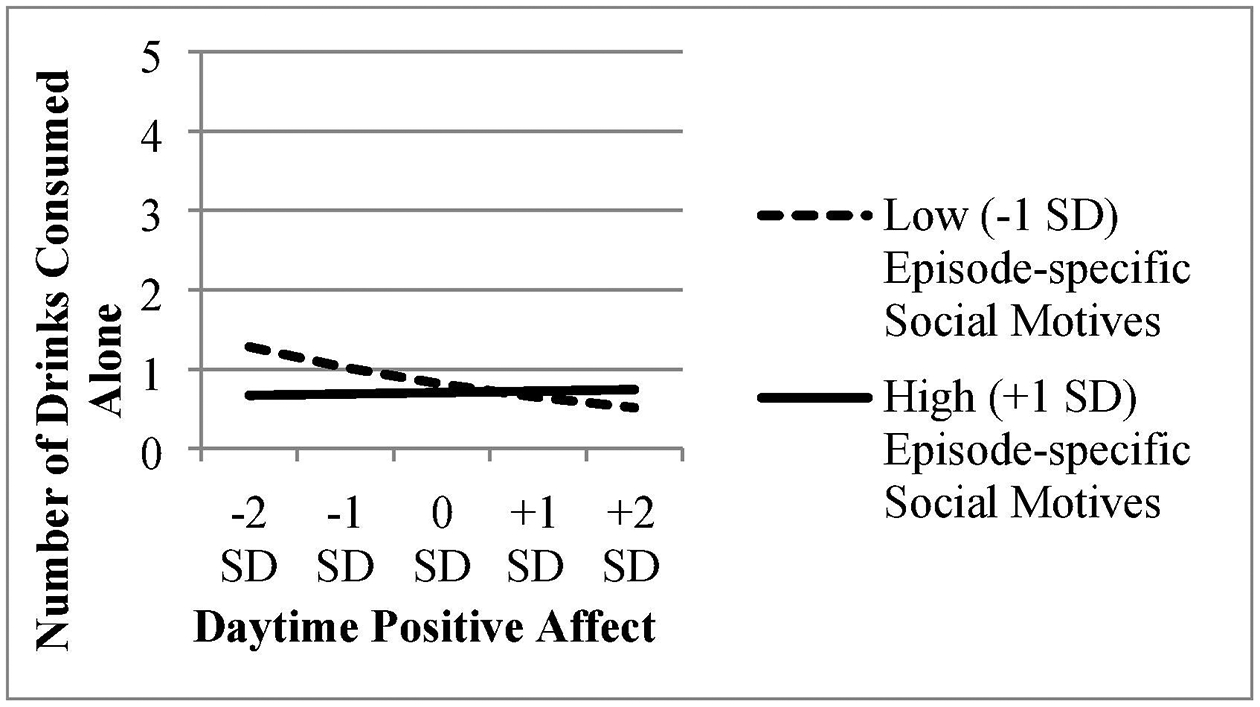

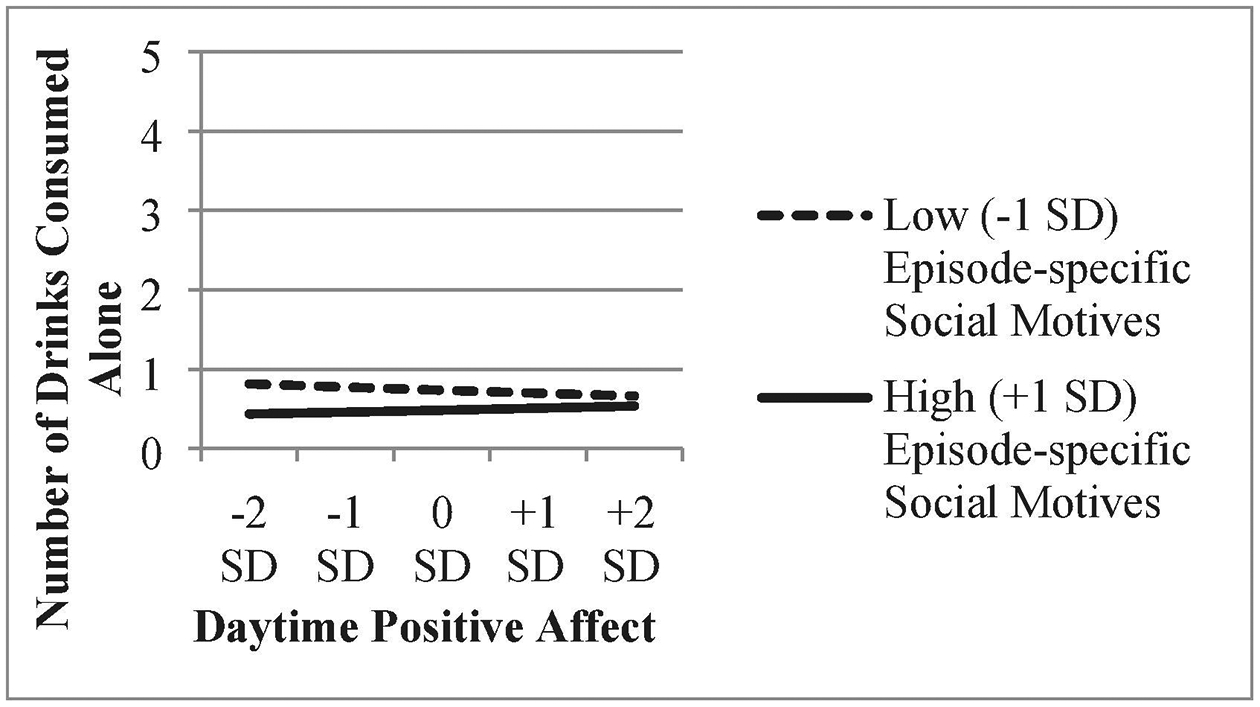

Probing of the significant Social motives × Positive affect × Wave interaction revealed a significant Social motives × Positive affect interaction during Wave 1, b=0.63, SE=0.18, Exp(B)=1.88, χ2(1, N=12128)=11.94, p=.001, but not during Wave 2, b=−0.11, SE=0.22, Exp(B)=0.90, χ2(1, N=12128)=0.25, p=.62. Further probing revealed that, during Wave 1, there was no effect of positive affect on solitary drinking when social motives were high, b=0.05, SE=0.10, Exp(B)=1.05, χ2(1, N=12128)=0.19, p=.66. In contrast, when social motives were low during Wave 1, positive daytime affect was related to lower solitary drinking, b=−0.44, SE=0.21, Exp(B)=0.66, χ2(1, N=12128)=4.22, p=.04 (see Figures 5a & 5b). Among college students, less daytime positive affect is related to greater solitary drinking when drinking episodes are less socially motivated.

Figure 5a.

Number of Drinks Consumed Alone as a Function of Episode-Specific Social Motives and Positive Affect During Wave 1

Figure 5b.

Number of Drinks Consumed Alone as a Function of Episode-Specific Social Motives and Positive Affect During Wave 2

4. Discussion

Contrary to hypotheses, episode-specific coping motives did not moderate the association between daytime negative affect and evening alcohol consumption alone or with others. However, the influence of coping motives was moderated by Wave. Episode-specific coping motives were related to greater social consumption during college and to greater solitary consumption after participants left college. This may explain why drinking to cope becomes more problematic over time (see Littlefield et al., 2010). Given the negative consequences associated with solitary consumption (Keough et al., 2018), further research into these associations among young adults is needed. Both college students and young adults may benefit from training in adaptive coping techniques to replace alcohol consumption.

Although the simple effects are not fully consistent with hypotheses, social motives moderated the association between positive affect and solitary consumption during Wave 1. Among college students who reported that they were less social motivated, lower daytime positive affect was related to greater evening solitary drinking. This suggests that episode-specific social drinking motives may protect against solitary drinking among college students. That is, when students are motivated to drink to enjoy their social interactions, solitary consumption is lower.

Finally, positive affect, conformity, enhancement motives, and social motives predicted greater social drinking, although the effects of social and enhancement motives on social alcohol consumption were stronger after college. This adds to research suggesting that drinking motives and affect have different associations with drinking occurring in different social contexts (see Mohr et al., 2005). Previous results regarding the association between negative affect and consumption have been mixed (see Armeli et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2009; also see Dvorak et al., 2014 for a comparison of between-versus within-person effects) and the current study did not find an association between negative affect and alcohol consumption alone or with others. We suggest that the reason research does not find robust associations between negative affect and drinking level might be because, in many instances, it is dealt with in adaptive ways (e.g., problem-focused coping). When adaptive coping fails or individuals lack the cognitive resources to engage in adaptive coping, individuals may turn to alcohol (see DeHart et al., 2014). This may explain why some studies examining daily experiences have found that negative affect negatively predicts drinking whereas positive affect predicts greater consumption (Bresin & Fairbairn, 2019; Howard et al., 2015). Future research is needed to test this possibility.

The current study extends previous research by examining factors related to alcohol consumption among participants during college and after they had left college. College students and young adults showed similar positive associations between drinking to conform and social drinking. Consistent with research on drinking norms (Hamilton et al., 2020), this finding suggests that young adults continue to feel pressure to drink as a means of fitting in with friends. This may be one reason why not all students mature out of risky drinking following graduation (see Beseler et al., 2012; Campbell & Demb, 2008). Participants consumed more alcohol with others when they reported greater drinking to cope motivation while they were still in college. However, when participants had moved past college, drinking to cope was related to solitary drinking. This suggests that young adults continue to engage in maladaptive coping after college and this shift from social to solitary drinking when drinking to cope may point to a more problematic type of alcohol consumption.

This study did have some limitations. Positive and negative affect were measured only once during the day. Future researchers should consider measuring affect more proximally to drinking episodes (see Bresin & Fairbairn, 2019). In addition, although this study advances research by measuring episode-specific drinking motives, a modified version of Cooper’s (1994) measure was used and social, enhancement, and conformity motives were measured using only two items each. Although it is important to reduce participant burden when designing daily diary surveys, future researchers should consider using all original scale items. Internal consistency of scales in the current study were also low. Future researchers may also wish to consider daytime drinking which, although rare in the current study, was not accounted for in the current results. It is possible that daytime affect prompted drinking behavior during the day rather than later that evening. Finally, the current study examined alcohol consumption rather than consequences. Future research should examine negative consequences as well, particularly given the direct links between drinking motives and consequences (Merrill et al., 2014).

4.1. Conclusions

The current study extends previous research on the associations between affect, drinking motives, and alcohol consumption by examining episode-specific drinking motives rather than trait-level drinking motives. Results support these episode-specific drinking motives as predictors of alcohol consumption among college students and young adults. Further, results suggest that these drinking motives have different relations with alcohol consumption occurring alone versus with others and that these associations change after individuals leave college. By increasing understanding of the motivations for alcohol consumption, these results may help to inform efforts to reduce the negative consequences of drinking through training in adaptive coping techniques.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Associations among affect, motives, and alcohol consumption were complex

Positive affect and non-coping motives were associated with greater social drinking

Positive affect predicted less solitary drinking in low socially motivated students

Coping related to social drinking in college, solitary drinking after college

Statement 1: Role of Funding Sources

Funding for this study was provided by NIAAA Grants 5P60-AA003510 and 5T32-AA007290. NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This study was preregistered at https://osf.io/w9gnq/?view_only=9362a1c6ede7419da5851325204ada6c. There has been no prior dissemination of the results of the analyses presented in the current manuscript in any presentation or written format.

Statement 3: Conflict of Interest

All of the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Author Agreement

All authors have seen and approved the final version of this manuscript. The article is the authors’ original work, hasn’t received prior publication, and isn’t under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Hypotheses preregistered at https://osf.io/w9gnq/?view_only=9362a1c6ede7419da5851325204ada6c

Due to a coding error, 23 individuals invited to Wave 2 did not meet the heavy drinking criteria but reported drinking levels at Wave 1 (using a drinking composite comprised of standardized retrospective and daily drinking variables) within the range of values for individuals who met criteria and were included in the current study.

Additional information and exact measures in supplementary materials.

Measure reliabilities presented here are calculated across all subjects and days. Supplementary materials include reliabilities at days 2, 15, and 29.

This differs from NIAAA guidelines of 1.5-oz. liquor assuming 80 proof rather than 100 or greater.

Including all participants who completed at least one Wave 2 diary survey did not change results (see supplementary materials for results with non-compliant participants included).

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeau KJ, Kuiken D, & Wild TC (2011). Drinking to enhance and to cope: A daily process study of motive specificity. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 1174–1183. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Conner T,S, Cullum J, & Tennen H (2010). A longitudinal analysis of drinking motives moderating the negative affect-drinking association among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24, 38–47. 10.1037/a0017530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beseler CL, Taylor LA, Kraemer DT, & Leeman RF (2012) Latent class analysis of DSM-IV alcohol use disorder criteria and binge drinking in undergraduates. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36, 153–161. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01595.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilevicius E, Single A, Rapinda KK, Bristow LA, & Keough MT (2018). Frequent solitary drinking mediates the associations between negative affect and harmful drinking in emerging adults. Addictive Behaviors, 87, 151–121. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresin K, & Fairbairn CE (2019). The association between negative and positive affect and alcohol use: An ambulatory study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80, 614–622. 10.15288/jsad.2019.80.614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CM, & Demb A (2008). College high risk drinkers: Who matures out? And who persists as adults? Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 52, 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 6, 117–128. 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A, Barber LL, & Wolf S (2015). Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco In Sher KJ (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use Disorders (pp. 375–421). 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199381678.013.0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, & Klinger E (1988). A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 168–180. 10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHart T, Peterson JL, Richeson JA, & Hamilton HR (2014). A diary study of daily perceived mistreatment and alcohol consumption in college students. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 36, 443–451. 10.1080/01973533.2014.938157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Pearson MR, & Day AM (2014). Ecological momentary assessment of acute alcohol use disorder symptoms: Associations with mood, motives, and use on planned drinking days. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22(4), 285–297. 10.1037/a0037157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Pearson MR, Sargent EM, Stevenson BL, & Mfon AM (2016). Daily associations between emotional functioning and alcohol involvement: Moderating effects of response inhibition and gender. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 163, S46–S53. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg E, Armeli S, Howland M, & Tennen H (2016). A daily process examination of episode-specific drinking to cope motivation among college students. Addictive Behaviors, 57, 69–75. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautreau C, Sherry S, Battista S, Goldstein A, & Stewart S (2015). Enhancement motives moderate the relationship between high-arousal positive moods and drinking quantity: Evidence from a 22-day experience sampling study. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34, 595–602. 10.1111/dar.12235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, & Mohr CD (2009). Coping-anxiety and coping-depression motives predict different daily mood-drinking relationships. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23, 226–237. 10.1037/a001500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton HR, Armeli S, Litt M, & Tennen H (2020). The new normal: Changes in drinking norms from college to postcollege life. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. Advance online publication. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/adb0000562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AL, Patrick ME, & Maggs JL (2015). College student affect and heavy drinking: Variable associations across days, semesters, and people. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29, 430–443. 10.1037/adb0000023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong A, Galloway CA, & Feagans LA (2005). Coping motives as a moderator of daily mood-drinking covariation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66, 344–353. 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Bolger N, & Kashy DA (1998). Data analysis in social psychology In Gilbert D & Fiske ST (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 1, 4th ed., pp. 233–265). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Keough MT, O’Connor RM, Sherry SB, & Stewart SH (2015). Context counts: Solitary drinking explains the association between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems in undergraduates. Addictive Behaviors, 42, 216–221. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keough MT, O’Connor RM, & Stewart SH (2018). Solitary drinking is associated with specific alcohol problems in emerging adults. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 285–290. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, & Diener E (1992). Promises and problems with the circumplex model of emotion In Clark MS (Ed.), Review of personality and social psychology, No. 13. Emotion (p. 25–59). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, & Wood PK (2010). Do changes in drinking motives mediate the relation between personality change and “maturing out” of problem drinking? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 93–105. 10.1037/a0017512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Wardell JD, & Read JP (2014). Drinking motives in the prospective prediction of unique alcohol-related consequences in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(1), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.15288%2Fjsad.2014.75.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Temple M, Todd M, Clark J, & Carney MA (2005). Moving beyond the keg party: A daily process study of college student drinking motivations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19, 392–403. 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB (2001). Multilevel random coefficients analyses of event- and interval-contingent data in social and personality psychology research. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 771–785. 10.1177/0146167201277001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell R, Richardson B, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Liknaitzky P, Arulkadacham L, Dvorak R, & Staiger PK (2019). Ecological momentary assessment of drinking in young adults: An investigation into social context, affect and motives. Addictive Behaviors, 98 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara RE, Armeli S, & Tennen H (2015). College students’ drinking motives and social-contextual factors: Comparing associations across levels of analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29, 420–429. 10.1037/adb0000046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau GS, Irons JG, & Correia CJ (2011). The reinforcing value of alcohol in a drinking to cope paradigm. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118, 1–4. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrzynski CJ, & Creswell KG (2020). Associations between solitary drinking and increased alcohol consumption, alcohol problems, and drinking to cope motives in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 10.1111/add.15055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson BL, Dvorak RD, Kramer MP, Peterson RS, Dunn ME, Leary AV, & Pinto D (2019). Within- and between-person associations from mood to alcohol consequences: The mediating role of enhancement and coping drinking motives. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(8), 813–822. 10.1037/abn0000472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A, & Clark D (1998). Alcohol consumption in university students: The role of reasons for drinking, coping strategies, expectancies, and personality traits. Addictive Behaviors, 23, 371–378. 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)80066-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.