Abstract

Background and Aim

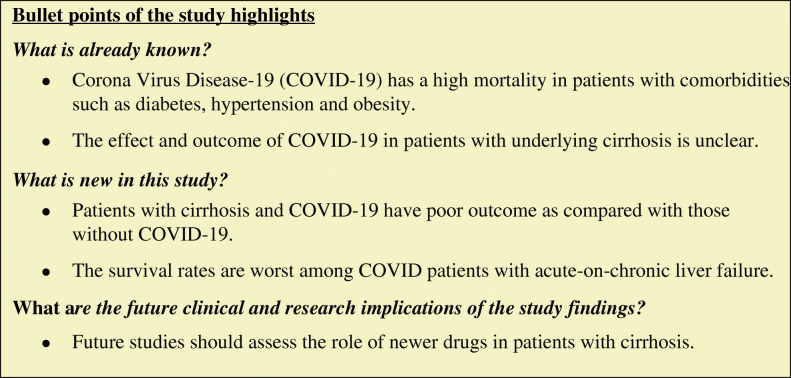

There is a paucity of data on the clinical presentations and outcomes of Corona Virus Disease-19 (COVID-19) in patients with underlying liver disease. We aimed to summarize the presentations and outcomes of COVID-19-positive patients and compare with historical controls.

Methods

Patients with known chronic liver disease who presented with superimposed COVID-19 (n = 28) between 22 April 2020 and 22 June 2020 were studied. Seventy-eight cirrhotic patients without COVID-19 were included as historical controls for comparison.

Results

A total of 28 COVID-19 patients (two without cirrhosis, one with compensated cirrhosis, sixteen with acute decompensation [AD], and nine with acute-on-chronic liver failure [ACLF]) were included. The etiology of cirrhosis was alcohol (n = 9), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (n = 2), viral (n = 5), autoimmune hepatitis (n = 4), and cryptogenic cirrhosis (n = 6). The clinical presentations included complications of cirrhosis in 12 (46.2%), respiratory symptoms in 3 (11.5%), and combined complications of cirrhosis and respiratory symptoms in 11 (42.3%) patients. The median hospital stay was 8 (7–12) days. The mortality rate in COVID-19 patients was 42.3% (11/26), as compared with 23.1% (18/78) in the historical controls (p = 0.077). All COVID-19 patients with ACLF (9/9) died compared with 53.3% (16/30) in ACLF of historical controls (p = 0.015). Mortality rate was higher in COVID-19 patients with compensated cirrhosis and AD as compared with historical controls 2/17 (11.8%) vs. 2/48 (4.2%), though not statistically significant (p = 0.278). Requirement of mechanical ventilation independently predicted mortality (hazard ratio 13.68). Both non-cirrhotic patients presented with respiratory symptoms and recovered uneventfully.

Conclusion

COVID-19 is associated with poor outcomes in patients with cirrhosis, with worst survival rates in ACLF. Mechanical ventilation is associated with a poor outcome.

Keywords: Acute-on-chronic liver failure, Acute decompensation, Chronic liver disease, COVID-19, Hepatic failure, Inflammation, Liver, Liver function tests, Pandemic, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

Since 30 January 2020, when India reported its first case of Corona Virus Disease-19 (COVID-19) caused by the novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome–Corona Virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the total number of cases have increased to 4,40,462 as of 22 June 2020 [1]. Although the COVID-19 predominantly presents as a respiratory illness in most patients, extrapulmonary manifestations also have been described [2]. The tropism of the virus to angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptors [3] and its presence on the hepatic endothelial cells and cholangiocytes [4] may predispose to direct hepatotoxic injury [5].

Liver enzyme derangements are common, seen in 14% to 53% of COVID-19 cases [2]. The clinical consequences are not well known in patients without liver disease since the majority of these derangements are mild in nature and hence clinically inconsequential [6]. However, their impact on patients with underlying liver diseases is beginning to emerge. Evolving data from a global registry suggest a poor outcome in patients with cirrhosis. Among these, 45% presented with new decompensation and the mortality rate was 33%. In contrast, 303 patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) without cirrhosis fared better with a mortality rate of 8% [7].

Genetic variability across the world can potentially impact the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection, which accounts for a myriad of possible presentations and outcomes. However, there is a paucity of data on the presentations and outcomes of COVID-19 patients with underlying liver diseases from different parts of the world. We report our experience of patients with liver disease and COVID-19.

Methods

Patient population

In this observation study, all consecutive patients with known liver disease presenting between 22 April 2020 and 22 June 2020 were included. Patients were diagnosed as COVID-19 based on oro-/naso-pharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid (RNA) positive result on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as per the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) criteria [8]. Data were collected from a prospectively maintained database of all patients from admission until endpoint of the study (discharge or death or deadline of 22 June 2020).

We compared the results of COVID-19-positive cirrhosis patients with age-, sex-, and severity-matched cirrhosis patients without COVID-19 (historical controls) from previously published data from our center [9, 10].

Patient evaluation and treatment

All consecutive patients with liver disease presenting to the emergency services with either fever or respiratory symptoms or chest X-ray showing infiltrates were tested for COVID-19 as per the hospital policy. Patients who had no symptom or tested negative initially were offered to retesting based on the development of new respiratory symptoms or fever at the discretion of the treating physician. Nasal and throat swabs were taken and transported in a viral transport media (Hank’s balanced salt solution) and tested by RT-PCR. Patients with confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia were offered broad-spectrum antibiotics, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) with or without ivermectin according to the evolving consensus [11]. Complications of liver disease including organ failures were managed according to the standard guidelines [12].

Definitions

Abnormalities in the liver function tests (LFTs) were based on our hospital cut-off values—bilirubin (> 1 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (AST > 40 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT >40 IU/L), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP > 280 IU/L). Cirrhosis was defined by the presence of a nodular outline of liver on imaging and concomitant evidence of portal hypertension, such as a dilated portal vein and splenomegaly. Patients with cirrhosis who had a current history of variceal bleed, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or jaundice were labeled as having acute decompensation (AD). Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) was defined according to the European Association the Study of the Liver (EASL)–chronic liver failure (CLIF) consortium definition—characterized by a hepatic or extrahepatic insult in a patient with underlying CLD and associated with prespecified organ failure [13]. The clinical presentations were defined as complications of cirrhosis as mentioned above and as respiratory when the presentation was predominantly with cough, breathlessness, and pneumonia. The hospital stay was counted onwards from the date of COVID-19 diagnosis for cases diagnosed during their hospitalization and from the date of admission for those who presented with a positive test. The clinical severity of COVID-19 was defined according to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) criteria as follows—mild disease as patients with only upper respiratory tract symptoms without any signs of breathlessness and hypoxia. Moderate severity was defined as the presence of pneumonia with the respiratory rate (RR) between 24 and 30/min and SpO2 between 90% and 94% on room air while the severe disease was defined by the presence of pneumonia with RR > 30/min or SpO2 < 90% on room air or severe respiratory distress [14].

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and skewed data were expressed as median with interquartile range. Nominal data were expressed as frequency and percentage. Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparing continuous data as appropriate. The Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables as applicable. Univariate and multivariate Cox-regression analysis was performed for analysis of predictors of in-hospital mortality. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistical software (Version 20.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical clearance

In this retrospective analysis requirement of consent was waived off. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Results

A total of 750 COVID-19 positive patients were admitted during the study period. Of these 28 (3.7%) patients had an underlying liver disease- 26 patients had liver cirrhosis, one each had non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and extrahepatic portal venous obstruction (EHPVO). Among patients with cirrhosis, one had compensated cirrhosis, 16 had AD, and 9 presented with ACLF. The median age of patients was 48 (38–58) years, and 20 (71.4%) were males. The etiology of cirrhosis was alcohol-related in 9 (34.6%), NAFLD in 2 (7.7%), hepatitis B virus (HBV) in 3 (11.5%), hepatitis C virus (HCV) in 2 (7.7%), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) in 4 (15.4%), and cryptogenic cirrhosis in 6 (23.1%).

Presentations and outcomes

Patients without cirrhosis

Both non-cirrhotic patients, one with NAFLD and other with EHPVO, presented with respiratory symptoms. None of the two developed liver-related complications. The LFTs were normal at admission in both the patients. The patient with EHPVO was pregnant at the time of admission and had gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Both these patients recovered uneventfully without the need for oxygen or mechanical ventilation.

Patients with compensated cirrhosis

One patient had NAFLD-related compensated cirrhosis with baseline Child-Pugh-Turcotte (CTP) score of 5, and a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 9. His associated comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (DM) and coronary artery disease (CAD). He presented with respiratory symptoms and developed ACLF (grade III) during his hospital stay with respiratory, cardiovascular, and renal failures. The patient succumbed to multiorgan failure on day 4 of hospital admission. COVID-19 was severe in this patient.

Patients with AD

Sixteen patients had AD. The mean age was 48.6 ± 10.6 years, and 12 (75%) were males. The clinical presentations included primarily features of AD in 10 (62.5%), AD as well as respiratory complications in 5 (31.3%), and respiratory alone in one (6.3%). Among the 10 patients presenting with AD, 8 had upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) and 2 had ascites. In the combined presentation, AD included 3 with UGIB and 2 with ascites, and in respiratory 4 had pneumonia and one had upper respiratory tract infection. One patient presented with pneumonia alone and during the hospital stay developed UGIB. Nine (56.3%) of these patients had a history of DM. The causes of cirrhosis included alcohol in 6 (37.5%), HBV, HCV, and NAFLD in 1 (6.3%) each, AIH in 2 (12.5%), and cryptogenic in 5 (31.3%). The LFTs were as follows—bilirubin 1.4 ± 0.8 mg/dL, AST 50 (37–82) IU/L, ALT 29 (19–42) IU/L, ALP 102 (75–299) IU/L, albumin 3.0 ± 0.8 g/dL, and international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.3 ± 0.2. The mean CTP and MELD scores were 7.2 ± 1.6 and 12.1 ± 3.1, respectively. At presentation deranged LFT values included bilirubin (> 1 mg/dL) in 10 (62.5%), AST (> 40 IU/L) in 10 (62.5%), ALT (> 40 IU/L) in 4 (25%), ALP (> 280 IU/L) in 4 (25%). Median hospital stay was 8 (6–17) days in 16 patients with AD. Of these, 15 (93.8%) recovered and were discharged. One patient (6.3%) required invasive mechanical ventilation and succumbed to illness after developing grade III ACLF (cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, and cerebral failure). Overall, COVID-19 severity was mild in 14 (87.5%), and moderate and severe in 1 (6.3%) each.

Patients with ACLF

Nine patients had ACLF at presentation; the mean age was 47.4 ± 13.6 years, and 6 (67%) were males. Of these 9 patients, grade I, II, and III ACLF were present in 3 (33%), 2 (22.2%), and 4 (44.4%), respectively. The causes of cirrhosis included alcohol in 3 (33%), HBV and AIH in 2 (22%) each, and HCV and cryptogenic in one (11%) each. The clinical presentations included complications of cirrhosis along with respiratory complaints in 6 (67%), complications of cirrhosis alone in 2 (22%), and only respiratory complaints in one patient.

Three (33%) patients with ACLF had DM. The LFTs were as follows—bilirubin 5.3 (3.4–18.4) mg/dL, AST 75 (61–140) IU/L, ALT 37 (25–59) IU/L, ALP 174 (88–489) IU/L, albumin 2.8 ± 0.7 g/dL, and INR 2.6 ± 1.2.

The mean CTP, MELD score, and chronic liver failure–consortium organ failure (CLIF-C OF) and CLIF-C ACLF scores were 11.1 ± 0.9, 28.4 ± 7.7, 13.8 ± 2.7, and 58.0 ± 13.6, respectively. At presentation, deranged bilirubin and AST were seen in all, ALT in 4 (44%) and alkaline phosphatase in 4 (44%). Of the 9 patients with ACLF, all died over a median hospital stay of 7 (5–8) days. The cause of death was acute respiratory distress syndrome with multiorgan failure in all 9 (100%) patients. Overall, COVID-19 was severe in 7 (77.8%), and mild and moderate in 1 (11.1%) patient each.

Comparison of characteristics between cirrhotic patients with COVID-19 and historical controls

We compared COVID-19 patients with cirrhosis (n = 26) with age-, sex-, and severity-matched historical controls (n = 78), from a previously published data from our center (Table 1). There was no difference in characteristics between the COVID-19-positive cases and historical controls except platelet count and alkaline phosphatase, which were higher in historical controls.

Table 1.

Comparison of patients with cirrhosis and Corona Virus Disease-19 (COVID-19) and historical controls with cirrhosis

| Characteristics | COVID-19-positive (n = 26) | Historical controls–cirrhosis patients (n = 78) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 48.5 ± 12.1 | 49.1 ± 11.7 | 0.804 |

| Sex, male n (%) | 19 (73.1%) | 56 (71.8%) | 1.000 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | 0.923 | ||

|

Alcohol Viral AIH Cryptogenic Others |

9 (34.6%) 5 (19.2%) 4 (15.4%) 6 (23.1%) 2 (7.7%) |

27 (34.6%) 14 (17.9%) 8 (10.3%) 24 (30.8%) 5 (6.4%) |

|

| Clinical presentation | 0.817 | ||

|

Compensated cirrhosis and AD ACLF |

17 (65.4%) 9 (34.6%) |

48 (61.5%) 30 (38.5%) |

|

| ACLF grade (I/II/III) | 3/2/4 | 10/6/14 | 0.988 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.8 ± 3.2 | 8.7 ± 2.9 | 0.864 |

| Total leukocyte count (per mm3) | 7070 (5075–12,900) | 8500 (4775–10,875) | 0.719 |

| Platelet count (× 103/mm3) | 71.5 (47.5–119.2) | 101.5 (61.5–161.2) | 0.020 |

| INR | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 0.355 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.1 (1.0–4.2) | 2.0 (0.9–6.9) | 0.747 |

| Creatinine | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 1.2 ± 1.0 | 0.266 |

| AST (IU/L) | 67 (43–108) | 63 (40–126) | 0.867 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 30 (22–50) | 42 (24–78) | 0.067 |

| Alk P (IU/L) | 111 (85–303) | 268 (195–406) | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 0.123 |

| CTP | 8.6 ± 2.3 | 9.5 ± 2.8 | 0.149 |

| MELD | 18.1 ± 9.6 | 19.6 ± 10.2 | 0.528 |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 11 (42.3%) | 18 (23.1%) | 0.077 |

AD acute decompensation, ACLF acute-on-chronic liver failure, AIH autoimmune hepatitis, ALT alanine aminotransferase, Alk P alkaline phosphatase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, CTP Child-Turcotte-Pugh, HBV hepatitis B virus, HCV hepatitis C virus, INR international normalized ratio, MELD model for end-stage liver disease

Overall, the mortality rate was higher in cirrhosis patients with COVID-19 (11/26 [42.3%] vs. 18/78 [23.1%]), though the difference just fell short of statistical significance (p = 0.077). The mortality rate among COVID-19 patients presenting as ACLF was 100% (9/9), while that in historical controls with ACLF was 53.3% (16/30) (p = 0.015). The mortality rate among COVID-19 patients presenting as compensated cirrhosis and AD was 11.8% (2/17), compared with 4.2% (2/48) among historical controls (p = 0.278). There were no differences between the prognostic scores of ACLF patients with COVID-19 and historical controls—MELD (28.4 ± 7.7 vs. 30.9 ± 6.6, p = 0.347), and CLIF-C ACLF score (58.0 ± 13.6 vs. 50.8 ± 10.7, p = 0.107).

Predictors of mortality

On univariate analysis, the factors significant for outcome among COVID-19 patients were total leukocyte count (TLC), total bilirubin, creatinine, INR, CTP score, MELD score, and requirement of invasive ventilation (Table 2). On multivariate analysis only mechanical ventilation was independently associated with mortality HR, 13.680 (1.390–134.582, P = 0.025) after adjusting for MELD, and TLC.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of predictors of in-hospital mortality among patients with COVID-19 and cirrhosis of liver

| Variable | Univariate hazard ratio (HR) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 1.024 (0.969–1.083) | 0.397 |

| Sex, female n (%) | 1.277 (0.329–4.959) | 0.723 |

| Diabetes, present | 0.648 (0.183–2.297) | 0.501 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 1.043 (0.874–1.245) | 0.637 |

| Total leukocyte count (per mm3) | 1.061 (0.989–1.138) | 0.096 |

| Platelet count (× 103/mm3) | 1.002 (0.996–1.009) | 0.468 |

| INR | 1.482 (1.000–2.195) | 0.050 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.060 (1.009–1.114) | 0.021 |

| Creatinine | 1.504 (1.010–2.238) | 0.044 |

| AST (IU/L) | 1.005 (0.999–1.012) | 0.109 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 1.013 (.984–1.043) | 0.372 |

| Alk P (IU/L) | 1.002 (0.999–1.005) | 0.188 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.943 (0.404–2.200) | 0.891 |

| CTP | 1.680 (1.205–2.341) | 0.002 |

| MELD | 1.084 (1.026–1.146) | 0.004 |

| Requirement of invasive ventilation | 18.858 (2.406–147.809) | 0.005 |

ALT alanine aminotransferase, Alk P alkaline phosphatase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, CTP Child-Turcotte-Pugh, INR international normalized ratio, MELD model for end-stage liver disease

Use of COVID-19 specific drugs

Twenty-five patients received specific drugs for COVID-19: HCQ 21 (84%), low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) 5 (20%), vitamin C 22 (88%), zinc 10 (40%), azithromycin 20 (80%), ivermectin 13 (52%), and methylprednisolone 5 (20%).

Discussion

In this analysis from a tertiary care center in India, we describe the clinical presentations and outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with underlying liver disease. Over 8 weeks, we included 28 patients with underlying liver disease presenting with COVID-19. A higher number of patients reported in the latter part of the study were in accordance with the increasing incidence of COVID-19 in India [15]. Overall, COVID-19 severity was mild in 15 (57.7%), moderate in 2 (7.7%), and severe in 9 (34.6%). We observed that COVID-19 patients with cirrhosis presented with complications of cirrhosis in 12 (46.2%), respiratory symptoms in 3 (11.5%), and combined complications of cirrhosis and respiratory symptoms in 11 (42.3%). The high rate of respiratory symptoms is expected as SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted via the respiratory route. Our data suggest that cirrhosis patients presenting with respiratory symptoms and recent onset of decompensation/deterioration of underlying liver disease should be evaluated for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Patients with cirrhosis and ACLF are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 because of impaired immune status. We observed patients with compensated cirrhosis deteriorate after COVID-19. Furthermore, none of ACLF patients with concomitant COVID-19 survived in our study, as compared with 47% survival rate in ACLF patients of historical control. The presence of pneumonia in more than 50% of patients in the COVID-19 group could have led to a higher proportion of patients developing AD and ACLF. On multivariate analysis, we found requirement of invasive ventilation to be an independent predictor of outcome in COVID-19 patients. The higher mortality rates in COVID-19 patients could possibly be because of extrahepatic organ failures especially respiratory failure. The severity of lung injury and CLIF-C has been associated with poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients with cirrhosis [16]. Pulmonary vascular changes including capillary microthrombi are common in patients with COVID-19 [17]. The exact mechanisms related to poor outcomes need exploration.

The outcome parameters in our study are similar to those reported by a multicenter registry (dated 19 June 2020)—(Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus) Under Research Exclusion (SECURE)-CIRRHOSIS registry and EASL supported COVID-Hep [7]. The registry reported the outcome of 833 patients with CLD. Of the 303 patients with CLD without cirrhosis, the requirement of invasive ventilation was 18% and mortality was 8%. Among the 379 patients with cirrhosis (alcohol 32%, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis 20%, viral 18%, and alcohol and HCV combined 5%), decompensation occurred in 45%, the requirement of invasive ventilation was 19%, and death occurred in 33%. Among the 151 liver transplant (LT) patients, the requirement of invasive ventilation was 19% and death occurred in 19% of patients. These results suggest that patients with cirrhosis are at a higher risk of mortality post-COVID-19.

Infections are common in patients with ACLF and are associated with poor outcomes [9]. Whether SARS-CoV-2 infection outcomes are similar to other acute precipitants, including bacterial infection in patients developing ACLF, is unclear. A recent study reported poor outcomes in COVID-19-patients as compared with those with bacterial infection [16]. The definite management of ACLF is LT. The current society guidelines differ in their opinion regarding LT in the current scenario. The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) recommends not to postpone transplants as it is an essential medical service while the EASL and Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) recommend restricting transplants to those with poor short-term prognosis [18]. The medical treatment options that have been tried for the management of COVID-19 patients include drugs like hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, other antivirals, and plasma therapy. None of these therapies has been shown to definitely improve the outcome. Moreover, most of these have hepatic side effects. Therefore, there is an urgent need for effective therapies to improve outcomes. We followed the standard recommendation for the management of all complications. For patients who presented with UGIB, we delayed endoscopy and managed patients with vasoconstrictors like terlipressin and patients were started on carvedilol for secondary prophylaxis [19]. All the patients could be managed medically without an increased risk of rebleeding.

We found that the proportion of patients with COVID-19 with alcoholic etiology of CLD was less as compared with our previous experience [20]. In the pre-COVID era, the highest fraction of CLD patients admitted was due to alcohol etiology [9]. Lockdown was implemented by the Indian government, and alcohol was not available; this could be a reason, and another possible reason could be the fact the borders of the states were sealed, which would reduce the number of patients reaching the hospital.

The derangement of LFTs at presentations has been reported in up to 50% of patients without liver disease [21]. The exact significance of the rise in transaminases and its relation to outcomes is unclear. The rise in liver enzymes could be multifactorial due to drugs side effects, associated ischemic hepatitis, and possibly related to SARS-CoV-2 infection per se or the associated cytokine storm [2].

Limitations of the study include its descriptive nature. Due to a small number of patients, we cannot rule out chances of type II statistical errors. The comparison group was taken from historical control admitted during different time frame. The drug therapies varied as per the evolving guidelines and treating team’s consensus. Our center is a tertiary care center; the proportion of patients with advanced liver disease was higher as compared with chronic hepatitis and compensated cirrhosis. Our results need to be validated in larger sample size before generalization.

In conclusion, COVID-19 in patients presenting as ACLF is associated with a poor outcome. Overall, in cirrhotic patients, COVID-19 appears to confer higher mortality as compared with those without it. Mechanical ventilation is associated with a poor outcome. In the absence of definite therapies available for COVID-19, it is imperative to prevent COVID-19 infection in patients with cirrhosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Clinical Research Unit, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi. We thank the Department of Emergency Medicine, Department of Anaesthesiology, Pain Medicine and Critical Care and Department of Laboratory Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi.

We thank Dr. Upendra Baitha, Dr. Srikant Mohta, and Dr. Chandan Palle for their contribution in patient management and data collection. We thank Prof. Subrat Kumar Acharya for critically reviewing the manuscript.

Name of the department and institutions where the work was done: Department of Gastroenterology and Human Nutrition and dedicated COVID-19 facility Jai Prakash Narayan Apex Trauma Centre (JPNATC), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Author contributions

Shalimar: study design, patient management, data analysis, manuscript drafting, and revision of the manuscript

Anshuman Elhence, Manas Vaishnav, and Piyush Pathak: patient management, data collection, and manuscript drafting

Ramesh Kumar: critical review of the manuscript

Kapil Dev Soni, Richa Aggarwal Manish Soneja, Pankaj Jorwal, Arvind Kumar, Puneet Khanna, Akhil Kant Singh, Ashutosh Biswas, Neeraj Nischal, Lalit Dar, Aashish Choudhary, Krithika Rangarajan, Anant Mohan, Pragyan Acharya, Baibaswata Nayak, Deepak Gunjan, Anoop Saraya, Soumya Mahapatra, Govind Makharia, Anjan Trikha and Pramod Garg: patient management, data collection, revision of the manuscript

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

S, AE, MV, RK, PP, KDS, RA, MS, PJ, AK, PK, AKS, AB, NS, LD, AC, KR, AM, PA, BN, DG, AS, SM, GM, AT, and PG declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

The authors declare that the study was performed in a manner conforming to the Helsinki declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008 concerning human and animal rights. The study was carried out after approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi (Ref No: IEC 253/17.04.2020).

Disclaimer

The authors are solely responsible for the data and the content of the paper. In no way, the Honorary Editor-in- Chief, Editorial Board Members, or the printer/publishers are responsible for the results/findings and content of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.India’s first case of coronavirus confirmed in Kerala [Internet]. Inshorts - Stay Informed. [cited 2020 Jun 10]. Available from: https://inshorts.com/en/news/indias-first-case-of-coronavirus-confirmed-in-kerala-1580372444417

- 2.Elhence A, Shalimar. COVID-19: beyond respiratory tract. J Dig Endosc. 2020;11:24–6.

- 3.Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis M, Lely A, Navis G, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai X, Hu L, Zhang Y, et al. Specific ACE2 expression in cholangiocytes may cause liver damage after 2019-nCoV infection. bioRxiv. 2020;2020(02):03.931766. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangash MN, Patel J, Parekh D. COVID-19 and the liver: little cause for concern. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:529–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Phipps MM, Barraza LH, LaSota ED, et al. Acute liver injury in COVID-19: prevalence and association with clinical outcomes in a large US cohort. Hepatology. 2020. 10.1002/hep.31404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.weeklyupdate_20200619_web.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.covid-hep.net/img/weeklyupdate_20200619_web.pdf

- 8.Strategey_for_COVID19_Test_v4_09042020.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 10]. Available from: https://www.icmr.gov.in/pdf/covid/strategy/Strategey_for_COVID19_Test_v4_09042020.pdf

- 9.Shalimar, Rout G, Jadaun SS, et al. Prevalence, predictors and impact of bacterial infection in acute on chronic liver failure patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:1225–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rout G, Sharma S, Gunjan D, Kedia S, Saraya A, Nayak B, Singh V, Kumar R, Shalimar Development and validation of a novel model for outcomes in patients with cirrhosis and acute variceal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:2327–2337. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05557-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.RevisedNationalClinicalManagementGuidelineforCOVID1931032020.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 10]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/RevisedNationalClinicalManagementGuidelineforCOVID1931032020.pdf

- 12.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu, European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:406–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426–1437. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ClinicalManagementProtocolforCOVID19.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/ClinicalManagementProtocolforCOVID19.pdf

- 15.COVID19 Statewise status [Internet]. MyGov.in. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 12]. Available from: https://mygov.in/corona-data/covid19-statewise-status/

- 16.Iavarone M, D’Ambrosio R, Soria A, et al. High rates of 30-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and COVID-19. J Hepatol. 2020. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Lau G, Ward JW. Synthesis of liver associations recommendations for hepatology and liver transplant care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Liver Dis. 2020;15:204–209. doi: 10.1002/cld.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta V, Rawat R, Shalimar, Saraya A. Carvedilol versus propranolol effect on hepatic venous pressure gradient at 1 month in patients with index variceal bleed: RCT. Hepatol Int 2017;11:181–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Shalimar, Kedia S, Mahapatra SJ, et al. Severity and outcome of acute-on-chronic liver failure is dependent on the etiology of acute hepatic insults: analysis of 368 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:734–741. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai Q, Huang D, Yu H, et al. COVID-19: abnormal liver function tests. J Hepatol. 2020. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]