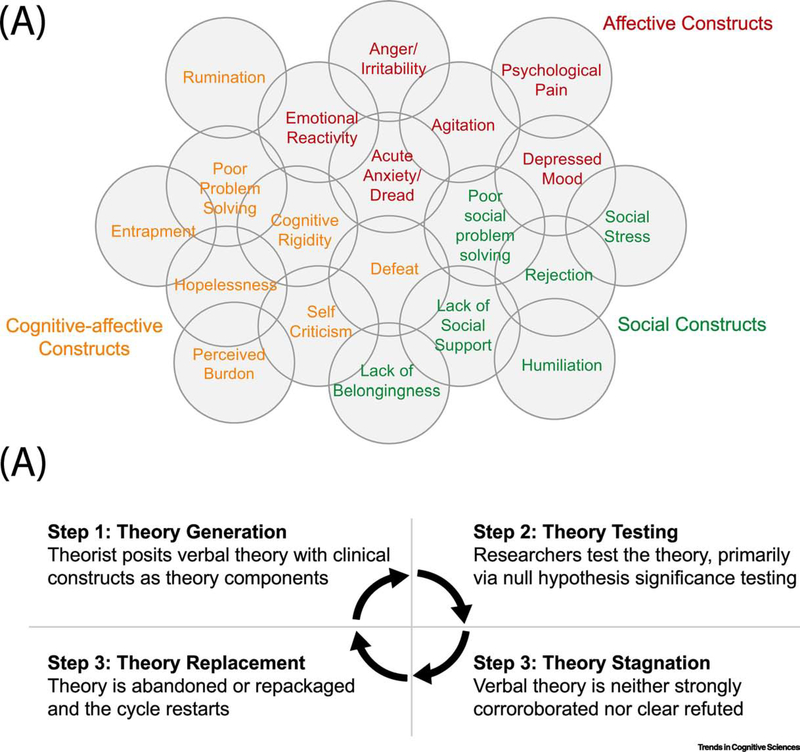

Figure 1. Current approaches to the development of suicide theories. (a) Clinical constructs used in suicide theories are intercorrelated.

As Meehl [28,29] pointed out, most variables in a given domain, such as clinical psychology, tend to have some non-zero correlation, which he referred to as the “crud factor." Meehl’s focus was on correlations among distinct constructs. In suicide research, this problem is exacerbated by conceptual overlap among many constructs (e.g., lack of belongingness and an absence of social support). Note that many constructs displayed apart are conceptually overlapping and correlated (e.g., lack of belongingness and psychological pain [86]). (b) The life cycle of current approaches to suicide theory. Theories proceed through four stages. Step 1: a theory is generated with components that often are intercorrelated and conceptually overlapping with many other clinical constructs. Step 2: support for the theory is obtained often through the use of null hypothesis tests. Because constructs often have non-zero correlations with other clinical constructs, including suicidal thoughts and behavior, the null hypothesis is often rejected, particularly when statistical power is high. Step 3: theory testing continues to produce significant findings. However, these findings provide neither strong support nor unambiguous refutation of the theory. Further, they provide little guidance for how the theory might be modified and theoretical stagnation takes hold. Step 4: it becomes clear that the theory cannot advance understanding and it is replaced, leading the cycle to begin again. Notably, this cycle typically plays out over the course of decade or more, leading to slow progress in suicide theory.