Abstract

Background

Bicruciate-retaining TKA has been proposed to improve clinical outcomes by maintaining intrinsic ACL function. However, because the unique design of the bicruciate-retaining tibial component precludes a tibial stem, fixation may be compromised. A radiostereometric analysis permits an evaluation of early migration of tibial components in this setting, but to our knowledge, no such analysis has been performed.

Questions/purposes

We performed a randomized controlled trial using a radiostereometric analysis and asked, at 2 years: (1) Is there a difference in tibial implant migration between the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining TKA designs? In a secondary analysis, we asked: (2) Is there a difference in patient-reported outcomes (Oxford Knee Score [OKS] and Forgotten Joint Score [FJS] between the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining TKA designs? (3) What is the frequency of reoperations and revisions for the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining TKA designs?

Methods

This parallel-group trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01966848) randomized 50 patients with an intact ACL who were eligible to undergo TKA to receive either a bicruciate-retaining or cruciate-retaining TKA. Patients were blinded to treatment allocation. The primary outcome was the maximum total point motion (MTPM) of the tibial component measured with model-based radiostereometric analysis (RSA) at 2 years postoperatively. The MTPM is a translation vector defined as the point in the RSA model that has the greatest combined translation in x-, y- and z-directions. A 1-year postoperative mean MTPM value of 1.6 mm has been suggested as a threshold for unacceptable increased risk of aseptic loosening after both 5 and 10 years. The repeatability of the MTPM was found to be 0.26 mm in our study. Patient-reported outcome measures were assessed preoperatively and at 2 years postoperatively with the OKS (scale of 0-48, worst-best) and FJS (scale of 0-100, worst-best). Baseline characteristics did not differ between groups. At 2 years postoperatively, RSA images were available for 22 patients who underwent bicruciate-retaining and 23 patients who underwent cruciate-retaining TKA, while patient-reported outcome measures were available for 24 patients in each group. The study was powered to detect a 0.2-mm difference in MTPM between groups (SD = 0.2, significance level = 5%, power = 80%).

Results

With the numbers available, we found no difference in MTPM between the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining groups. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) MTPM was 0.52 mm (0.35 to 1.02) and 0.42 mm (0.34 to 0.70) in the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining groups, respectively (p = 0.63). There was no difference in the magnitude of improvement in the OKS from preoperatively to 2 years postoperative between the groups (median delta [IQR] for bicruciate-retaining 18 [14 to 23] versus cruciate-retaining 18 [15 to 21], difference of medians 0; p = 0.96). Likewise, there was no difference in the magnitude of improvement in the FJS score from preoperatively to 2 years postoperative between the groups (mean ± SD for bicruciate-retaining 46 ± 32 versus cruciate-retaining 48 ± 16, mean difference, 2; p = 0.80). Three patients in the bicruciate-retaining group underwent arthroscopically assisted manipulation at 3 to 4 months postoperatively, and one patient in the bicruciate-retaining group sustained a tibial island fracture during primary surgery and underwent a revision procedure after 6 months. There were no reoperations or revisions in the cruciate-retaining group.

Conclusions

With the numbers available, we found no differences between the bicruciate-retaining and the cruciate-retaining implants in terms of stable fixation on RSA or patient-reported outcome measure scores at 2 years, and must therefore recommend against the routine clinical use of the bicruciate-retaining device. The complications we observed with the bicruciate-retaining device suggest it has an associated learning curve and the associated risks of novelty with no demonstrable benefit to the patient; it is also likely to be more expensive in most centers. Continued research on this implant should only be performed in the context of controlled trials.

Level of Evidence

Level II, therapeutic study.

Introduction

The clinical aim of the bicruciate retaining TKA design is to maintain the knee’s natural kinematics, stability, and proprioception by retaining functionally intact ACL and PCL ligaments. It is based on the idea that even in the setting of a TKA, important intrinsic ACL functions could potentially be maintained [21]. Historically, shortcomings of the bicruciate-retaining TKA designs have been the risk of tibial eminence fracture due to the technically challenging operative procedure, an increased polyethylene wear rate, and increased risk of aseptic loosening [14]. Modern bicruciate-retaining designs seek to remedy some of the historical problems.

Tibial implant fixation is particularly important for the bicruciate-retaining TKA because the horseshoe-shape baseplate design required to maintain an intact ACL is markedly different from the design of standard and well-proven implants having a large tibial component keel. A few studies have reported the clinical outcome of bicruciate-retaining TKA after its reintroduction [3, 14, 20]. In a retrospective study comparing the bicruciate-retaining design with a well-proven cruciate-retaining TKA of similar design, there was concern about implant survivorship and radiographic findings for the bicruciate-retaining TKA [3], and the authors suggested further evaluation using a randomized design. Radiostereometric analysis (RSA) is a high-precision reference-standard metric to assess implant migration. The magnitude and pattern of migration act as predictors of long-term outcomes with respect to implant loosening [15]. To our knowledge, no previous studies have reported the outcome of RSA for a modern bicruciate-retaining TKA design.

We performed a randomized controlled trial using RSA and asked, at 2 years: (1) Is there a difference in tibial implant migration between the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining TKA designs? In a secondary analysis, we asked: (2) Is there a difference in patient-reported outcomes (Oxford Knee Score [OKS] and Forgotten Joint Score [FJS]) between the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining TKA designs? (3) What is the frequency of reoperations and revisions for the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining TKA designs?

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

We performed a single-blinded, randomized, controlled trial (NCT01966848) of 50 patients who provided written informed consent. Approvals were attained from the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics (Journal number H-1-2013-086) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (journal number HVH-2013-050). The reporting of this study conforms to the CONSORT guidelines [11] and RSA guidelines [24].

We used a computer-generated simple randomization sequence with a 1:1 allocation ratio. Allocation concealment was ensured by using sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelopes that were securely stored in a locked cabinet. All patients received the treatment to which they were randomized. Patients were blinded to their treatment allocation until after the 2-year follow-up interval. To detect a minimally important difference in the mean migration of the prosthesis between groups of 0.2 mm [19] (SD approximately 0.2), a sample size of 18 patients per group was necessary, with a 5% significance level and 80% power. We included 25 patients in each group to allow for dropouts.

Participants

We enrolled 50 patients from January 20, 2014 to September 8, 2015 at one orthopaedic department in Denmark. Inclusion criteria were patients with knee osteoarthritis who were eligible for primary unilateral cemented TKA, age older than 18 years as well as with the ability to read and understand Danish, to give informed consent, and expected ability to complete all postoperative visits and PROMs. Exclusion criteria were severe comorbidities (American Society of Anesthesiologists class greater than 3), terminal illness, rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory joint disease, medically treated osteoporosis, altered pain perception because of a comorbidity (for example, diabetes mellitus with neuropathy), prior open surgery or arthroscopic cruciate ligament surgery on the affected knee, history of high-energy trauma or cruciate ligament rupture in the affected knee, and suspicion of cruciate ligament rupture on clinical examination. Two experienced surgeons (AT, KSO) performed all eligibility assessments and subsequent surgeries.

We found no differences in preoperative patient demographics (Table 1) and osteoarthritis patterns between the two groups (see Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A276).

Table 1.

Preoperative demographics and clinical characteristics

Of the 50 randomized patients, two were excluded from the study; one patient in the bicruciate-retaining group sustained a tibial island fracture during primary surgery and underwent revision surgery 6 months postoperatively, and one patient in the cruciate-retaining group was unable to attend follow-up examinations because of alcoholism (the patient did not undergo a revision procedure). Another three patients were not available for analysis of the primary endpoint at 2 years, leaving 23 bicruciate-retaining patients and 22 cruciate-retaining patients available for analysis. Data from 48 patients were available for PROM analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

This flow diagram shows patient enrollment in our study; RSA = radiostereometric analysis.

Description of Experiment, Treatment, or Surgery

Patients were randomized to receive either the bicruciate-retaining Vanguard® XP or the Vanguard cruciate-retaining Total Knee System (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA). The surgeons were experienced in using the cruciate-retaining implant on a routine basis. For the newer bicruciate-retaining implant design, the surgeons performed two cadaveric surgeries each and two pilot procedures each before inclusion of study participants. The bicruciate-retaining TKA had a horseshoe-shaped symmetrical design of the tibial component, with pairs of pegs and keels for surface cementation. The cruciate-retaining TKA had a finned design. In both designs, the bearing surfaces were highly cross-linked vitamin E enhanced polyethylene. An anterior midline skin incision and medial parapatellar arthrotomy were used. The surgical procedures and instrumentation adhered to the manufacturer’s surgical technique manuals. The overall technique was measured resection and the patella was resurfaced in all procedures. Femoral preparation aimed at 5° of anatomic valgus, and rotation was set using anatomic landmarks (transepicondylar access) using an intramedullary guide. For the Vanguard cruciate-retaining tibial component, the tibia was resected to mimic the natural slope of the patient up to 7° of posterior slope, with protection of the PCL insertion. For the Vanguard XP tibial component, the two compartments were resected to mimic the natural slope of the patient up to 7° of posterior slope, with protection of the central bony island. For both, an extramedullary guide was used, and rotation was set according to anatomic landmarks (medial 1/3 of the tibial tuberosity). Ligament releases were performed as needed with trial implants in place. The surgeons evaluated knee balance during surgery using manual methods. A two-stage surface cementing technique (cement applied to the implant first, followed by pulsed lavage delivery and pressurization of cement into bone) was applied in both groups. Optipac® Refobacin® R bone cement (Zimmer Biomet) was used in all procedures. No tourniquet was used. The postoperative mobilization protocol was identical in both groups and involved immediate full weightbearing.

Variables, Outcome Measures, Data Sources, and Bias

RSA Analyses

The primary outcome was tibial component migration, measured with model-based RSA as the maximum total point motion (MTPM) 2 years after surgery [7]. The RSA method provides the specific translations (mm) in x-, y- and z- directions, and also rotation (°) of the component in relation to the bone. Our primary outcome, MTPM, is a translation vector defined as the point in the RSA model that has the greatest combined translation in x-, y- and z-directions [24]. RSA radiographs were obtained immediately postoperatively to determine the reference position of the components and were subsequently taken at 3 months and 1 and 2 years after surgery. Secondary migration outcomes were translation (mm) and rotation (°) in the x, y, and z directions at each follow-up timepoint. A standardized RSA setup and cut-off levels for analyses were used (see Supplemental Digital Content 2 and 3, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A276). One observer (MGT) performed RSAs with model-based RSA software version 4.11 (RSAcore, Leiden, the Netherlands). During surgery, a minimum of six to eight tantalum beads (1.0 mm in diameter; RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden) were placed in the proximal tibial metaphysis. Participants with fewer than three visible tantalum beads around the tibial component on RSA assays were excluded from the migration measurements. The repeatability of the RSA setup was investigated by performing two sets of stereoradiographs on all randomized patients at the 3-months follow-up visit. For the two groups combined, RSA repeatability, calculated as 1.96 * √2 * SD difference between the two measurements [18], was 0.26 mm for the MTPM and ranged from 0.05 mm to 0.16 mm of translation and from 0.13° to 0.60° of rotation (see Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A276).

Radiologic assessments were performed using standard AP and lateral radiographs obtained routinely preoperatively and 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively. The Kellgren-Lawrence classification of preoperative radiographic osteoarthritis severity and the postoperative limb alignment and component positioning of the tibia and femur components [5] was assessed by one experienced observer (LHI) [8].

Secondary Outcomes

PROMs (OKS [4, 12] and FJS [2, 22]) were evaluated preoperatively and at all postoperative follow-up visits. The 12-item OKS represents the degree of knee pain and functional limitations on a scale from 0 to 48, with 0 being the worst and 48 being the best [12]. The minimal important difference (MID), defined as the minimal difference in improvement in score between the two groups that is considered clinically meaningful, was suggested to be 5 points for the OKS [1]. The degree of knee awareness is captured by the 12-item FJS ranging from 0 to 100, representing a high to low degree of knee awareness [2]. Adverse events related to knee surgery, including postoperative infection, manipulation under anesthesia, and revision or reoperation surgeries were also recorded.

Statistical Analyses

All continuous variables were tested for normality using a visual interpretation of Quantile-Quantile plots and the Shapiro-Wilk test. All RSA data were non-normally distributed, and thus we used a Mann-Whitney U Test to assess the primary outcome of difference in the 2-year MTPM between the two groups. For interpretational purposes and to enable comparison with previous studies, both median (interquartile ranges [IQR]) values and the mean and SDs are presented for RSA data. For the remaining secondary outcomes, parametric and non-parametric statistics were used, as appropriate. As previously described, the sample size for the study was estimated based on the primary outcome, MTPM. Consequently, our study may not be sufficiently powered to detect clinically important differences in our secondary outcomes PROMs. All statistics were performed with R version 3.2.1., R-project.org (Vienna, Austria).

Results

Tibial Implant Migration

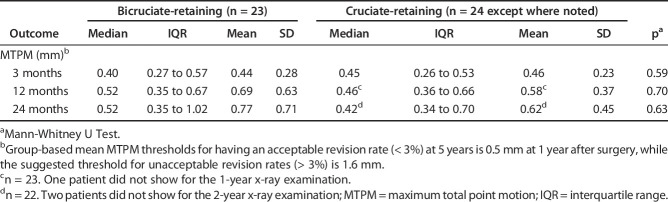

No clinically relevant between-group differences in tibial implant MTPM between the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining groups were found at any time-points analyzed (Fig. 2). At 2 years, the between-group difference in median MTPM was 0.1 mm (p = 0.63). Similarly, at 3 months and 1 year, the differences in median MTPM were 0.06 mm (p = 0.59) and 0.05 mm (p = 0.70), respectively (Table 2). RSA results for each translation direction and rotation were comparable across groups (see Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A276).

Fig. 2.

This graph shows the MTPM of the bicruciate-retaining (blue line) and cruciate-retaining (red line) tibial implants at 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively. Error bars present the 95% CI. MTPM = maximum total point motion.

Table 2.

The MTPM at 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively, respectively, for the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining groups

Two patients in the bicruciate-retaining group and one patient in the cruciate-retaining group were considered migration outliers (MTPM at 2 years above the group-specific mean + [2*SD]). For these three patients, most migration occurred up until 1 year, and stabilized from 1 to 2 years (bicruciate-retaining, 2.8 to 3.0 and 1.8 to 2.3; cruciate-retaining, 1.6 to 1.8 mm MTPM from 1 to 2 years). Excluding these patients from the mean MTPM results resulted in 2-year mean MTPM values of 0.59 and 0.56 for the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining groups, respectively. All three patients had good clinical outcomes scores, with OKS of 41, 43, and 46 at 2 years.

Patient-reported Outcomes

There was no difference in the magnitude of improvement in the OKS from preoperatively to 2 years after surgery between the groups (median delta [IQR] for bicruciate-retaining 18 [14 to 23] versus cruciate-retaining 18 [15 to 21], difference of medians 0; p = 0.96). Likewise, there was no difference in the magnitude of improvement in the FJS score from preoperatively to 2 years after surgery between the groups (mean ± SD for bicruciate-retaining 46 ± 32 versus cruciate-retaining 48 ± 16, mean difference 2 [95% CI -17 to 13]; p = 0.80) (Table 3). At 2 years, postoperative median (IQR) OKS were 41 (35 to 44) and 44 (40 to 46) and mean ± SD FJS values were 62 ± 28 and 70 ± 20 for the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining groups, respectively. However, the study is underpowered to detect clinically relevant differences between the groups in these measures.

Table 3.

Change from preoperative to 2-year follow-up of OKS and FJS

Reoperations and Revisions

Although the numbers were too small to compare statistically, the number and kinds of reoperations and complications in the bicruciate-retaining group were concerning. One patient in the bicruciate-retaining group sustained a tibial island fracture during primary surgery and subsequently underwent a revision procedure 6 months postoperatively. Three patients in the bicruciate-retaining group underwent arthroscopically assisted manipulation of the knee 3 to 4 months postoperatively because of flexion limitations and arthrofibrosis. There were no reoperations or revisions in the cruciate-retaining group.

Discussion

When novel TKA designs are introduced, comparisons should be made to well-established TKA designs. It has been suggested that bicruciate-retaining TKA designs may improve performance by maintaining the intrinsic ACL function. However, unique design features of the bicruciate-retaining tibial component have previously been shown to compromise stable fixation [14, 21]. Implant migration is best assessed using RSA, the high-precision reference-standard metric for such studies. Our study, the first we know of to report on RSA for a bicruciate-retaining TKA tibial component, showed no difference in 2-year implant migration compared with a cruciate-retaining TKA design, and no differences in clinical outcomes scores. The kinds of complications and the frequency of complications in the bicruciate-retaining group were concerning. Our findings lead us to recommend against the routine clinical use of the bicruciate-retaining device, until or unless future studies demonstrate its superiority.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include the relatively short follow-up period, and longer-term clinical and radiologic follow-up is needed to further investigate the efficacy of this bicruciate-retaining design. Aseptic loosening is a frequent cause of implant revision after primary TKA [17]. However, when RSA is used to assess implant migration, it only considers the risk of later revision because of fixation failure. Supplemental data should be considered, depending on relevance, for a full evaluation of a new design. The sample size estimation in our study was based on the primary RSA outcome. Consequently, our study sample was too small to judge whether there were meaningful differences in PROM scores. For the OKS, the MID, defined as the minimal difference in improvement between groups that can be judged clinically relevant was suggested to be 5 points. We found that the median difference in OKS was 0; however, the small sample size may have masked a real difference between the groups. For the FJS, no clear guidelines for MID values exist, but likewise the small sample explains the wide confidence intervals around the estimated mean difference of 2 points. However, the PROMs used are validated metrics and our results are useful for generating hypotheses and future study designs seeking to evaluate the differences in clinical outcomes of bicruciate-retaining TKA [4, 22]. Another limitation is that even though the surgeons did not inform patients about their randomization group until the 2-year endpoint, we did not assess whether patients remained blinded to the design received. This is considered a limitation, since it could have potentially biased the patients’ notions of the perceived treatment effect, favoring the new design. However, this is not a limitation with regard to the primary outcome, since the RSA measurement cannot be subjectively biased.

Implant Migration

We found no differences between the study groups in terms of implant migration 2 years after surgery. Although our study is the first to assess bicruciate-retaining component migration using RSA technology, our results for the cruciate-retaining component showed somewhat lower mean MTPM migration at 2 years postoperatively of 0.62 mm, compared with previous findings of 0.80 mm using a comparable cemented approach [13]. The association between early migration, assessed with the MTPM, and later revision was established in a previous systematic review. The authors suggested that group-based mean MTPM thresholds for having an acceptable revision rate (< 3%) at 5 years is 0.5 mm at 1 year after surgery, while the suggested threshold for unacceptable revision rates (>3%) is 1.6 mm [16]. Our results show that both the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining implants have mean MTPM migrations at 1 year that lie in between these suggested acceptable and unacceptable thresholds. Furthermore, another systematic review evaluating migration patterns in the first 2 years postoperatively found that the largest degree of migration occurred within the first 6 months after surgery, followed by a stabilization period within the first 2 years. In accordance with previous RSA guidelines, the authors suggested that migration smaller than 0.2 mm MTPM should serve as a stabilization threshold between 1 and 2 years postoperatively [15, 19]. In our study, migration in both implants seemed to stabilize after 3 months. Between 1 and 2 years of follow-up, migration was well below the 0.2-mm threshold (Table 2). In contrast, the MTPM of Boneloc cement was found to be 1.25 1 year postoperatively, and the migration did not stabilize between 1 and 2 years postoperatively [15].

Patient-reported Outcomes

Although our study was not adequately powered to reveal a difference in PROM improvements, our results revealed no benefit to the newer (bicruciate-retaining) device over the traditional (cruciate-retaining) device at 2 years (Table 3). The median OKS at 2 years of 41 and 44 points for the bicruciate-retaining and cruciate-retaining groups, respectively, are comparable to scores in previous reports from other randomized controlled trials of knee arthroplasty designs [20, 23]. Furthermore, in both groups, we found that the OKS and FJS improved above the thresholds for minimal clinical important improvement (OKS: 8-point improvement; FJS: 14-point improvement) [6]. These findings suggest that important improvements in pain and function occur in both groups, but we cannot imply that there are any clinically relevant differences between groups, or that the groups present with similar clinical outcomes postoperatively. Future studies investigating the clinical outcomes of bicruciate-retaining should be adequately powered to investigate superiority. To adopt a new device, which has the risks associated with novelty and new or different complications such as we observed, the new device should demonstrate clear superiority, which we could not demonstrate in this study. Future studies investigating the clinical benefits of a bicruciate-retaining design should be adequately powered to enable solid conclusions about improvements in PROM.

Reoperations and Revisions

The complications and reoperations experienced in the bicruciate-retaining group were concerning. The tibial island fracture during bicruciate-retaining surgery and three reoperations performed in the bicruciate-retaining group for flexion limitations indicates there is a learning curve related to a risk of unnecessary tightness when retaining the intrinsic stabilizing properties of the ACL. This concern has been highlighted in previous studies investigating bicruciate-retaining designs, suggesting that the implantation may be technically difficult [3, 14]. While the cruciate-retaining design was well-known to the operating surgeons in this study, the bicruciate-retaining design was introduced at the time the study was initiated. The 25 operated patients in the bicruciate-retaining group could therefore still be considered part of the learning curve. Surgeons should be aware of this unique learning curve and pay extra attention to leaving the knee well-balanced to allow the natural activity and constraint of the ligaments and avoiding tightness of the knee.

Conclusion

With the numbers available, we found no differences between the bicruciate-retaining and the cruciate-retaining implants in terms of stable fixation on RSA or patient-reported outcome measure scores at 2 years, and must therefore recommend against the routine clinical use of the bicruciate-retaining device. Although the PROM scores were similar with the available study sample size, the bicruciate-retaining group had additional complications of tibial island fracture, flexion limitations, and arthrofibrosis that was treated with manipulation under anesthesia. The complications we observed with the bicruciate-retaining device suggest it has an associated learning curve with no demonstrable benefit to the patient, it is likely to be more expensive than the cruciate-retaining design in most centers, and has risks associated with its novelty, given the absence of available long-term follow-up with this implant. Further monitoring of treatment outcomes in adequately powered studies focusing on patient-reported outcomes, complications, and long-term revision rates is necessary before this design can be recommended over more established designs [9, 10].

Acknowledgments

We thank statistician, Thomas Kallemose MSc, for statistical support for this study.

Footnotes

The institution of one or more of the authors (AT, LHI, MGT, OM, KSO and HH) has received, during the study period, funding from Zimmer Biomet (Warsaw, IN, USA). One of the authors certifies that he (AT) has received or may receive payments or benefits, during the study period, an amount of USD 10,000 to USD 100,000 from Zimmer Biomet.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, Copenhagen, Denmark.

References

- 1.Beard DJ, Harris K, Dawson J, Doll H, Murray DW, Carr AJ, Price AJ. Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrend H, Giesinger K, Giesinger JM, Kuster MS. The “Forgotten Joint” as the ultimate goal in joint arthroplasty. Validation of a new patient-reported outcome measure. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:430-436.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen JC, Brothers J, Stoddard GJ, Anderson MB, Pelt CE, Gililland JM, Peters CL. Higher frequency of reoperation with a new bicruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gromov K, Korchi M, Thomsen MG, Husted H, Troelsen A. What is the optimal alignment of the tibial and femoral components in knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop. 2014;85:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingelsrud LH, Roos EM, Terluin B, Gromov K, Husted H, Troelsen A. Minimal important change values for the Oxford Knee Score and the Forgotten Joint Score at 1 year after total knee replacement. Acta Orthop. 2018;89:541–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaptein BL, Valstar ER, Stoel BC, Reiber HC, Nelissen RG. Clinical validation of model-based RSA for a total knee prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malchau H. Introducing new technology: a stepwise algorithm. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malchau H, Graves SE, Porter M, Harris WH, Troelsen A. The next critical role of orthopedic registries. Acta Orthop. 2015;86:3–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, Elbourne D, Egger M, Altman DG. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg. 2012;10:28–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray DW, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, Pandit H, Beard DJ, Carr A, Dawson J. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1010–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Øhrn FD, Van Leeuwen J, Tsukanaka M, Röhrl SM. A 2-year RSA study of the Vanguard CR total knee system: A randomized controlled trial comparing patient-specific positioning guides with conventional technique. Acta Orthop. 2018;89:418–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osmani FA, Thakkar SC, Collins K, Schwarzkopf R. The utility of bicruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today. 2017;3:61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pijls BG, Plevier JWM, Nelissen RGHH. RSA migration of total knee replacements: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Orthop. 2018;89:320–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pijls BG, Valstar ER, Nouta KA, Plevier JWM, Fiocco M, Middeldorp S, Nelissen RGHH. Early migration of tibial components is associated with late revision. Acta Orthop. 2012;83:614–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price AJ, Alvand A, Troelsen A, Katz JN, Hooper G, Gray A, Carr A, Beard D. Knee replacement. Lancet. 2018;392:1672–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranstam J, Ryd L, Onsten I. Erratum: Accurate accuracy assessment: Review of basic principles (Acta Orthop Scand 1999; 70 (4): 319-321). Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:106–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryd L, Albrektsson E, Carlsson L, Dansgaard F, Herberts P, Regnér L, S T-L. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scarvell JM, Perriman DM, Smith PN, Campbell DG, Bruce WJM, Nivbrant B. Total knee arthroplasty using bicruciate-stabilized or posterior-stabilized knee implants provided comparable outcomes at 2 years: A prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled, clinical trial of patient outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:3356-3363.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stiehl JB, Komistek RD, Cloutier JM, Dennis DA. The cruciate ligaments in total knee arthroplasty: a kinematic analysis of 2 total knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomsen MG, Latifi R, Kallemose T, Barfod KW, Husted H, Troelsen A. Good validity and reliability of the forgotten joint score in evaluating the outcome of total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2016;87:280–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tjørnild M, Søballe K, Møller Hansen P, Holm C, Stilling M. Mobile-vs. Fixed-bearing total knee replacement: A randomized radiostereometric and bone mineral density study. Acta Orthop. 2015;86:208–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valstar ER, Gill R, Ryd L, Flivik G, Börlin N, Kärrholm J. Guidelines for standardization of radiostereometry (RSA) of implants. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:563–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]