Abstract

Measuring the translational diffusion of proteins under physiological conditions can be very informative, especially when multiple diffusing species can be distinguished. Diffusion NMR or diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) is widely used to study molecular diffusion, where protons are used as probes, which can be further edited by the proton-attached heteronuclei to provide additional resolution. For example, the combination of the backbone amide protons (1HN) to measure diffusion with the well-resolved 1H/15N correlations has afforded high-resolution DOSY experiments. However, significant amide-water proton exchange at physiological temperature and pH can affect the accuracy of diffusion data or cause complete loss of DOSY signals. Although aliphatic protons do not exchange with water protons and thus are potential probes to measure diffusion rates, 1H/13C correlations are often in spectral overlap or masked by the water signal, which hampers the use of these correlations. In this report, a method was developed that separates the nuclei used for diffusion (alpha protons, 1Hα) and those used for detection (1H/15N and 13C’/15N correlations). This approach enabled high-resolution diffusion measurements of polypeptides in a mixture of biomolecules, thereby providing a powerful tool to investigate coexisting species under physiological conditions.

Graphical Abstract

Proteins in cells exist in the crowded milieu of biomolecules under physiological conditions.1,2 Because translational diffusion rates provide information on the size, shape, and neighboring environment of molecules, diffusion measurements under physiological conditions provide insight into native protein function. Owing to the rich information that the diffusion rates provide, many techniques have been developed to measure molecular diffusion.3–6 However, when a sample contains a mixture of different molecules or if a molecule exists in multiple conformations, it is difficult to determine the diffusion rate of each species separately.

Diffusion NMR7–10 is a powerful technique to measure molecular diffusion rates. Because the diffusion dimension can be appended to chemical shift dimensions to provide additional resolution when required, diffusion NMR is also called diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY).11,12 In a typical DOSY experiment, the diffusion delay is sandwiched between the encoding and decoding gradients. In the absence of diffusion during the diffusion delay period, the encoding and decoding gradients form a perfect gradient-echo and a strong DOSY signal is observed. When diffusion takes place during this delay, the location-dependent gradient-encoded phase is scrambled and an imperfect gradient-echo generates a weaker DOSY signal. The extent of gradient encoding/decoding, which depends on the gradient strength and gyromagnetic ratio of nuclear spins, and the amount of diffusion, which depends on the diffusion delay and molecular diffusion rates, combine to define the DOSY signal intensities.

DOSY sequences can be combined with multidimensional frequency labeling for high-resolution diffusion measurements. Initially, 1H-DOSY was combined with two-dimensional (2D) 1H-correlation spectroscopy (1H-DOSY-1H-COSY)13 or 2D 1H-total correlation spectroscopy (1H-DOSY-1H-TOCSY)14 to give 2D spectra separated by molecular size. Similar experiments also enabled the determination of diffusion coefficients of individual molecules in a mixture, because the well-resolved 2D cross-peaks associated with particular molecules could be analyzed to provide individual diffusion coefficients.14,15 1H-DOSY combined with heteronuclear single quantum coherence,16,17 which we call 1H-DOSY-1H/13C-HSQC to be consistent with other nomenclature, or heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence (1H-DOSY-1H/13C-HMQC)18,19 has also enabled efficient analysis of diffusion rates for species in complex mixtures.

Protein NMR takes advantage of heteronuclear correlations to achieve residue-specific information. Observation of backbone amide 1H/15N correlations in a protein is commonly obtained because these correlations are well resolved and are clearly separated from the water signal. Thus, 1HN-DOSY has been combined with HMQC (1HN-DOSY-1H/15N-HMQC) or HSQC (1HN-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC) (Figure 1a) for many applications.20 For example, 1H/15N-detected 1HN-DOSY was employed to observe apomyoglobin after suppressing the signals from small molecules in a cell lysate,16 to monitor protein folding and association of collagen-like peptides,21 to analyze residue-specific proton exchange rates between amides and water,22,23 to identify the cleaved fragments of Engrailed 2 protein,24 and to simultaneously determine the diffusion rates of both the folded and unfolded states of an SH3 protein.25

Figure 1.

Diffusion NMR spectra obtained using distinct diffusion and detection probes. Diffusion measurement or diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) was performed at pH 7.4 and 35 °C on a peptide and alpha-synuclein (αS) at an encoding/decoding gradient value of 5.8 G/cm. (a) Diffusion measurement on amide protons followed by 1H/15N frequency labeling. Diffusion measurement on alpha protons followed by (b) 1H/15N and (c) 13C’/15N frequency labeling. Black curved arrows inside each scheme show magnetization transfer pathways.

1HN-DOSY experiments can take advantage of amide-selective pulses to accelerate the T1 relaxation of 1HN by maintaining the thermal bath of aliphatic protons,26 enabling fast repetition of transients and thereby increasing the overall NMR sensitivity.27 In principle, amide-selective excitation has no effect on water magnetization, and thus diffusion coefficients are not affected by proton exchange between amides and water. Amide-selective excitation under physiological conditions can accelerate T1 relaxation by yet another mechanism: exchange between thermally-polarized water protons and amide protons.28

However, at near physiological conditions, fast proton chemical exchange during the gradient-encoding, diffusion, gradient-decoding, and heteronuclear detection periods often causes complete loss of the 1H/15N-detected 1HN-DOSY signals. If the water proton is not gradient-encoded, the DOSY signal will disappear upon proton exchange. This exchange-driven signal loss is illustrated for a peptide and the intrinsically disordered alpha-synuclein (αS) protein (Figure 1a). If the water proton is gradient-encoded, the diffusion rates can be overestimated.

A common feature of all diffusion NMR methods described above is that the protons used for diffusion recording and NMR data acquisition are the same. Here, we present a method that measures diffusion on alpha protons (1Hα) that do not exchange with water protons, followed by transfer of the magnetization to the well-resolved 1H/15N or 13C’/15N correlations for high-resolution detection under near physiological conditions (Figure 1b,c). Note that the 1Haliphatic-DOSY-1H/13C-HSQC experiment would be free from the influence of amide-water proton exchange; however, it is often difficult to resolve and assign the 1H/13C correlations because of severe spectral overcrowding,29 especially for large proteins. Using the method described herein, diffusion analysis was performed successfully on a small peptide at pH 7.4 and 10 °C, the folded and unfolded states of the SH3 domain from Drosophila adaptor protein drk (drkN) at pH 8.0 and 20 °C, and αS interacting with lipid vesicles at pH 7.4 and 35 °C.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Diffusion measurements of the peptide

All NMR experiments were performed on a 850 MHz Bruker NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm z-axis gradient 1H [13C,15N]-TCI cryogenic probe, except for the experiments used for SH3 backbone assignments. For the 1D diffusion experiments, a 2 mM RKY*Y*KR sample was prepared in a buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 20 mM NaCl and 95%/5% H2O/D2O. The data for diffusion measurements were collected at 10 °C with a diffusion delay (Δ) of 150 ms, and encoding and decoding gradient width (δ/2) of 1.5 ms, and gradient strengths (Gauss/cm) of 5.1, 10.2, 14.1, 17.6, 21.0, 24.5, 28.1, and 31.8. The delay symbols are explained in Figure 2. For each gradient strength, 256 transients were averaged and the recycle delay was 2 s. For experiments with 1HN detection, 2,500 complex data points were sampled for 147 ms, and for experiments with 13C’ detection, 1,100 complex data points were sampled for 149 ms.

Figure 2.

Pulse sequences that separate nuclei used for diffusion and detection. Thin and thick black bars indicate 90° and 180° degree pulses, respectively, whereas the shaped lobes with E, Q and R on the top represent selective eburp, Q3, and reburp pulses, respectively.32,33 Delays were set to τ1 = 1.7 ms (= 1/4JHαCα), τ1’ = 1.25 ms (< 1/4JHαCα), τ2 = 4.7 ms (= 1/4JC’Cα), τ3 = 14 ms (= 1/4JC’N), and τ4 = 2.6 ms (= 1/4JNH). Δ is the diffusion delay, δ/2 is the width of a gradient in the bipolar pulse pair and τ is the distance between the gradient pairs. All phases of pulses are omitted from the sequence. Diffusion was measured on 1Hα followed by (a) 1H/15N-HSQC and (b) 13C’/15N-HSQC pulse schemes. Detailed parameters of the pulse sequences in the absence and presence of the convection compensation scheme are described in Figure S1 and S2, respectively

Diffusion measurements of the drkN SH3 domain

For the high-resolution diffusion experiments on the drkN SH3 domain, a 13C/15N-enriched 1 mM SH3 sample was prepared in a buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 20 mM NaCl, and 95%/5% H2O/D2O. 2D 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC experiments were performed with a diffusion delay (Δ) of 300 ms and gradient width (δ/2) of 1.5 ms at 20 °C. Five different gradient strengths (Gauss/cm) of 5.8, 10.8, 14.8, 18.7, and 22.6 were used to measure diffusion rates. Each experiment was acquired with a recycle delay of 2 s and a data matrix of 400 (t1, 15N) × 2000 (t2, 1H) complex points and sweep widths of 2,400 (15N) and 14,800 (1H) Hz. Sixteen scans were acquired for each FID, resulting in 10 h of data collection time for each gradient point. NMRPipe30 and NMRFAM-SPARKY31 were used for data processing and analysis, respectively.

Diffusion measurements for probing the interaction between αS and SUV

1D 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC and 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC experiments without frequency labeling in the indirect dimension were recorded to measure the diffusion rate of 1 mM αS in the presence and absence of 1 μM SUV (5 mM lipid molecules, 5:3:2 DOPE/DOPS/DOPC; Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL, USA, cat. no. 790304). The sample was prepared in a buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 20 mM NaCl, and 95%/5% H2O/D2O, and the experiments were performed at 35 °C. A diffusion delay (Δ) of 300 ms and gradient width (δ/2) of 1.5 ms was used. Gradient strengths (Gauss/cm) of 5.8, 11.5, 15.8, 19.8, 23.7, 27.5, 31.6, 35.8, and 40.2 were used to measure the diffusion coefficients. For each gradient strength, 256 transients were averaged and the recycle delay was 3 s. For the 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC experiment, 2,500 complex data points (1HN) were sampled for 147 ms, and for the 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC experiment, 1,100 complex data points (13C’) were sampled for 149 ms.

To measure the diffusion coefficient of SUV at 35 °C, 1 μM SUV were prepared in the buffer for αS experiments described above. 1Haliphatic-DOSY with a diffusion delay of 300 ms was used to monitor the DOSY attenuation profile of lipid methylene protons resonating at 1–1.5 ppm. Gradient strengths (Gauss/cm) of 5.8, 11.5, 15.8, 19.8, 23.7, 27.5, 31.6, 35.8, and 40.2 were used. For each gradient strength, 256 transients were averaged and 5,000 complex data points (1H) were sampled for 294 ms with a recycle delay of 3 s.

To measure the diffusion rate of dioxane, 5 mM 1,4-dioxane (Samchun, Pyeongtaek, Korea, cat. no. D1094) was added to the αS only, SUV only and αS + SUV samples described above and diffusion coefficients were measured at 35 °C. Gradient strengths (Gauss/cm) of 1.4, 2.8, 3.9, 4.8, 5.8, 6.7, 7.7, 8.7, and 9.8 were used and 5,000 complex data points (1H) were sampled for 294 ms with a recycle delay of 3 s. To calibrate the gradient strengths, the diffusion coefficient of HDO in a 0.1%/99.9% H2O/D2O sample at 25 °C was set to 19.02 × 10–10 m2 s–1.34

The details on the preparation of the peptide, proteins and lipid samples are described in the experimental section of the supporting information (SI).

RESULTS

Pulse sequences for high-resolution diffusion NMR

We present two HSQC-edited 1Hα-DOSY experiments. The first experiment involves a 1Hα-DOSY followed by a 1H/15N-HSQC (1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC), where diffusion measurements of non-labile 1Hα nuclei avoid complications from amide-water proton exchange while affording the higher resolution of 1H/15N detection. Because the intra-residue magnetization transfer of Hα(i) → Cα(i) → NH(i) → HN(i) also involves an unwanted magnetization transfer to NH(i+1), we have designed the magnetization transfer scheme to be Hα(i) → Cα(i) → C’(i) → NH(i+1) → HN(i+1) (Figure 2a), where the symbol in parenthesis denotes the relative residue position. Although chemical shift detection of the (i+1)-th residue is encoded with diffusion information of the i-th residue using the inter-residue magnetization transfer scheme, the coherences experience less T2 relaxation when compared with detection via the intra-residue magnetization transfer scheme.35–37

The diffusion measurement employs a stimulated-echo (STE) (Figure 2a) to store magnetization along the z-direction rather than the xy-plane during the diffusion delay, making the gradient-encoded magnetization experience T1 rather than T2 relaxation.38 In addition, bipolar gradient pulse pairs (BPP; (+)-gradient → 180° pulse → (–)-gradient) (Figure 2a) were used for gradient encoding and decoding to minimize the 1H-1H nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) during the diffusion delay, suppress artifacts from strongly coupled spin systems, reduce eddy currents, and refocus the deuterium lock signal.39 Further, we introduced an unbalanced BPP (the (+)-gradient is scaled by (1+α) and (–)-gradient is scaled by (1–α)), which is known as the one-shot sequence,40 to effectively eliminate signals that do not experience the 180° pulse in the BPP.

When the loss in NMR sensitivity due to amide-water proton exchange during the 1H/15N data acquisition period (red box in Figure 2a) outweighs the sensitivity gain obtained by observing 1H instead of 13C, diffusion measurements using 1Hα-DOSY can be followed by 13C’/15N detection (1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC) (Figure 2b) rather than the 1H/15N detection (Figure 2a). Additionally, this experiment can be used when the 13C’/15N correlations are better resolved than the 1H/15N correlations. Here, the magnetization flow is Hα(i) → Cα(i) → C’(i) → NH(i+1) → C’(i), where the last two steps enable 15N frequency labeling.

Convection of solvent inside an NMR tube can complicate diffusion analysis. Because convection causes unidirectional translational motion of molecules, the convection-compensation (CC) sequence can be employed to negate the effect of convection in diffusion measurements.44 This scheme, which is shown in Figure S2, modifies the DOSY sequence in the blue box of Figure 2a,b. The CC sequence compensates for convection but the NMR signal is reduced by 50%. The effect of convection in diffusion measurements should be checked when a regular 5 mm NMR tube is used with the temperature set above 30 °C and/or broadband decoupling applied.45

To calculate diffusion coefficients from NMR experiments, the gradient-strength-dependent attenuation profile of DOSY intensities is measured. For the BPP-STE (Figure 2, S1) and BPP-STE-CC (Figure S2) experiments, the relevant Stejskal-Tanner equations46 are

| (1) |

| (2) |

where g is the variable encoding and decoding gradient strength, go is the lowest gradient strength, I(g) is the NMR signal intensity at gradient strength g, D is the diffusion coefficient, γ is the proton gyromagnetic ratio, δ/2 is the width of the gradient length, τ is the distance between the gradient pairs, α is the BPP imbalance factor,40 and Δ is the diffusion delay. The expression inside the square bracket is often called the b factor, which is different between STE-BP and STE-BP-CC. The slope of the plot between the b factor and provides information on the diffusion coefficient. Normally, (b factor, ) data points are obtained for different g values and least squares fitting of the data points to a straight line provides the diffusion coefficient (Figures. 3, 4, and 5).

Figure 3.

Effect of amide-water proton exchange on the diffusion measurement of the RKY*Y*KR peptide at pH 7.4 and 10 °C. (a) Pulse schemes that are used to observe the effect of water perturbation on diffusion measurements. 1D DOSY experiment with amide selective pulses (1HN-DOSY), 1HN-DOSY with weak water saturation (1HN-DOSY-sat) and 1HN-DOSY with weak water saturation (CW) and a long recycle delay of 5 s (1HN-DOSY-long) were employed. The lobes with E, tr-E and R denote amide-selective eburp, time-reversed eburp and reburp pulses, respectively.32 The open rectangles above and below the horizontal lines indicate the bipolar gradient pulse pairs (BPP). The open lobes are crush gradients. (b) DOSY intensity attenuation profiles that illustrate the effect of water perturbation on diffusion measurements. Errors are calculated from the signal-to-noise ratio of NMR spectra. (c) Comparison of diffusion measurements performed by 1HN-DOSY and the experiments described in Figure 2, without frequency labeling in the indirect dimension.

Figure 4.

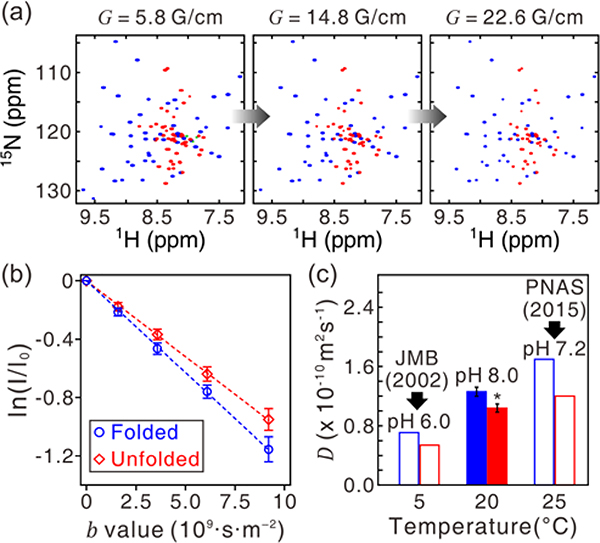

Simultaneous diffusion coefficient measurements of the folded and unfolded states of the drkN SH3 domain at pH 8.0 and 20 °C. (a) 2D 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC spectra of 13C/15N-enriched 1 mM SH3 domain with increasing gradient strengths. Signals from both the folded (blue) and unfolded (red) states are observed. Unassigned resonances are colored in green. The diffusion delay was set to 300 ms. (b) DOSY attenuation profile. Data points are the average of all well-resolved folded (n = 43) and unfolded (n = 35) peak intensities, where the error bars indicate ± 1σ of the intensities. (c) Comparison of the diffusion coefficients of the SH3 domain measured under different conditions. Diffusion coefficient of the folded state (*) is statistically different from that of the unfolded state (p < 0.001). The diffusion coefficients at pH 6.0 and 5 °C, and pH 7.2 and 25 °C are from Refs. 25 and 29, respectively.

Figure 5.

Probing the interaction between αS and lipid membranes under near physiological conditions of pH 7.4 and 35 °C. (a) DOSY attenuation profiles of 13C/15N-enriched 1 mM αS, and 1 mM αS with 5 mM lipid molecules (ca. 1 μM lipid vesicles). For each profile, results from the 1D 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC and 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC experiments obtained in two independently prepared samples were averaged. (b) DOSY attenuation profile of 5 mM 1,4-dioxane in water and with each sample described in (a). (c) DOSY attenuation profiles of the 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC experiment without the convection compensation scheme (CC) and with 15N decoupling, with neither CC nor decoupling, and with both CC and decoupling.

Effect of water saturation on the diffusion measurement of a peptide

We first tested how diffusion measurements are affected by water perturbation when employing amide protons as diffusion probes. We performed 1HN-DOSY in the absence and presence of weak water saturation during the diffusion delay (Figure 3a) on a six-residue RKY*Y*KR peptide, whose tyrosine residues (marked with asterisks) are 13C,15N-enriched. We then compared these results with the diffusion measurements performed with the pulse sequences described in the previous section. At pH 7.4 and 35 °C, the DOSY signal was only observed in the 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC experiment (Figure 2b) even when a low encoding/decoding-gradient strength was used (Figure 1). Thus, we performed all peptide experiments at pH 7.4 and 10 °C, where the amide protons (1HN) were detected. Regardless of the nuclei and experiment used for diffusion and detection, we observed nearly identical diffusion rates, except when 1HN-DOSY was performed with water saturation (Figure 3).

The correlation between the b factor (x-axis) and logarithm of DOSY signals (y-axis) is a straight line when the random translation of molecules is governed by a single diffusion coefficient (equations 1 and 2) and the initial magnetization is the same before each transient regardless of the encoding and decoding gradient strength applied. We observed a linear correlation when only amide-selective pulses were used in the diffusion measurement (1HN-DOSY) (Figure 3b). In contrast, weak 1H saturation on water (1HN-DOSY-sat) during the diffusion delay introduced an element of nonlinearity and generated a steeper slope (Figure 3b). We ascribe this effect to the decrease in radiation-damping-induced T1 relaxation rate of saturated water arising from the increase of gradient strength. This effect, in turn, decreases the T1 relaxation rate of amides,28 resulting in the decrease of the DOSY signal. When water protons were close to thermal polarization regardless of the applied gradient strengths by extending the recycle delay from 2 to 5s, the slope of the correlation decreased almost to the level of the 1HN-DOSY experiment without saturation (Figure 3b).

Note that there are a few mechanisms that can decrease the sensitivity of DOSY experiments without affecting the measured diffusion rate. For instance, the 1H-1H nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) can decrease the intensity of the DOSY signal, especially when the BPP scheme is omitted.47 In addition, labile protons from side chains that exchange with saturated water can reduce the signal-to-noise of DOSY by an exchange-relayed NOE. Additionally, signals from the gradient-encoded 1HNs that experience proton exchange with water during the diffusion delay will be removed by the decoding gradient, unless the water protons are also gradient-encoded. In the latter case, the measured diffusion rate will have a mixed contribution from the amide-bearing molecule and water.

Comparison of the results from 1HN-DOSY without water saturation to 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC and 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC experiments with no chemical shift evolution in the indirect dimension revealed nearly an identical correlation between the b factor and logarithm of DOSY signals (Figure 3c). Thus, consistent results were obtained when diffusion measurements are not affected by amide-water proton exchange. Note that although the pulse sequences in Figure 2 apply weak water saturation during the diffusion delay to suppress the water signal, this does not affect the diffusion measurement on non-labile alpha protons.

Diffusion measurement on the folded and unfolded states of SH3 at high pH

Different conformations of a molecule can be discriminated by their distinct diffusion rates by high-resolution diffusion measurements. Using non-labile Hα protons as diffusion probes and using the 1H/15N-HSQC experiment for detection (1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC) (Figure 2a), diffusion rates of the folded and unfolded states of the 13C/15N-enriched drkN SH3 domain at pH 8.0 and 20 °C were separately determined (Figure 4). This 59-residue domain is located at the N-terminus of the adaptor protein drk, and is marginally stable and exchanges between its folded and unfolded states.48 The exchange rate is slow (kex ~ 2 s–1)49,50 on the chemical shift and diffusion timescales.

With 1D 1Hα-DOSY, an average diffusion rate of the folded and unfolded states will be observed, without any effect from amide-water proton exchange. When 1Hα-DOSY was followed by an 1H/15N-HSQC, which can resolve most of the 1H/15N cross-peaks of the folded and unfolded states of SH3,48 it was possible to determine the diffusion rate of each state separately (Figure 4). The gradient-strength-dependent attenuation profile of DOSY intensities was measured with the 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC experiment (Figure 4a). Each data point in Figure 4b was obtained by averaging the intensities of the well-resolved 43 (35) backbone amide cross-peaks of the folded (unfolded) states of the SH3 domain at different gradient strengths. Note that the larger error range with stronger gradients (Figure 4b) reflects the concomitant decrease in the DOSY signal-to-noise.

The diffusion coefficients of the unfolded and folded drkN SH3 domain were assessed previously by other diffusion experiments. Initially, the 1HN-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC experiment that shares the diffusion delay with a 15N-frequency-labeling period was used to measure the SH3 domain diffusion rate at pH 6.0 and 5 °C.25 Under these conditions, no issues from amide-water proton exchange were present. In contrast, proton exchange may affect the measurement of the diffusion rate of the SH3 domain at pH 7.2 and 25 °C when using the 1HN-DOSY experiment. Thus, the 1Haliphatic-DOSY-1H/13C-HSQC was used to measure the diffusion rate of the SH3 domain at this higher pH and temperature. The diffusion measurement was confined to Hβ nuclei of a few alanine residues because these 1H/13C cross-peaks are easy to assign, well-resolved, and reasonably strong in intensity.29

The diffusion measurement of the drkN SH3 domain at pH 8.0 and 20 °C gave a diffusion coefficient for the folded state of (1.26 ± 0.06) × 10–10 m2 s–1, whereas the diffusion coefficient of the unfolded state was (1.04 ± 0.06) × 10–10 m2 s–1. Thus, the unfolded state diffuses ~17% more slowly than that of the folded state. This result is consistent with other experimental results at different pH and temperatures (Figure 4c).25,29 On the other hand, reducing the diffusion delay minimizes the effect of any exchange processes on the measured diffusion rate. The temperature dependence of the diffusion coefficient was clearly seen (Figure 4c).51–53

Probing protein-lipid interactions at near physiological conditions

Biomolecular interactions at near physiological conditions (pH 7.4 and 35 °C) were monitored using the pulse sequences described in Figure 2. Interaction between the N-terminal-acetylated αS and lipid membrane was observed by measuring the diffusion of αS in the presence and absence of small unilamellar vesicles (SUV). αS is a 140-residue protein that is present at high concentrations in presynaptic terminals of neurons.54 Although αS is highly water-soluble and possesses the characters of an intrinsically disordered protein, the function of αS is closely related to its interaction with lipid membranes.55–57

We collected αS diffusion data using the experiments in Figure 2 without 15N frequency labeling. The diffusion coefficient of a 1 mM αS sample was (8.06 ± 0.15) × 10–11 m2 s–1, whereas on the addition of 5 mM phospholipid (DOPE:DOPS:DOPC = 5:3:2) SUV to the sample caused a change in the diffusion coefficient of αS to (7.39 ± 0.09) × 10–11 m2 s–1 (Figure 5a). It is unlikely that αS experienced any amyloid formation under this condition.58 In the presence of SUV, the αS diffusion rate decreased while the correlation between the b factor and DOSY intensities remained linear (Figure 5a), indicating that αS experienced multiple lipid binding and release cycles during the 300-ms diffusion period. The change in the diffusion rate indicates that ca. 10% of αS is bound to SUV at pH 7.4 and 35 °C. This percentage was estimated by assuming that the diffusion coefficient of αS in the presence of SUV is the weighted average of the diffusion coefficient of SUV (2.86 × 10–11 m2 s–1) and free αS (Figure 5a) after taking in account the effect of viscosity and convection as explained in the following paragraphs. The methylene peaks at 1–2 ppm were monitored to measure SUV diffusion. Considering that the maximum number of αS that can bind to one SUV (30 nm in diameter; measured by DLS) is ca. 100 and that 5 mM lipid molecules corresponds to about 1 μM SUV,59 at most 10% of the αS molecules present in the sample can bind to SUV at any instant. This indicates that most of the SUV surface was occupied by αS under the experimental conditions employed.

Although the crowded macromolecular environment in a sample can differentially affect the translational diffusion of αS and small chemicals,60 the diffusion rate of a chemical was measured in different macromolecular environments to normalize the effect of viscosity as much as possible. Diffusion coefficients of 5 mM 1,4-dioxane measured in samples without macromolecules, with 1 mM αS and with both 1 mM αS and 5 mM lipid molecules gave values of 1.39 × 10–9, 1.28 × 10–9 m2 s–1 and 1.27 × 10–9 m2 s–1, respectively (Figure 5b). The decrease in the diffusion rate of dioxane in the presence of macromolecules is ascribed to a change in bulk viscosity, and this was later reflected in the calculation of the diffusion coefficients from Figure 5a to minimize the effect of viscosity.

To investigate the effect of convection on diffusion, we performed diffusion measurements on a 1 mM αS sample inside a Shigemi tube in the presence and absence of convection compensation (CC; equation 2, Figure S2). Note that Shigemi tubes were used in all other experiments. Convection can be substantial when an experiment is performed at high temperature or if a broadband decoupling scheme is applied. Because we performed our (control) experiments on αS at 35 °C with 15N broadband decoupling in both 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC and 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC pulse schemes, it is important to check the effect of convection. The diffusion coefficient of free αS decreased by 1.8% when CC was introduced to the control experiment with decoupling (Figure 5c). To determine whether convection is caused mainly by decoupling, we omitted the decoupling scheme in the control experiment and observed a 1.5% decrease in the diffusion coefficient (Figure 5c). In summary, although the effect of convection is small when using Shigemi tubes, slightly faster diffusion can be measured because of convection at high temperatures with decoupling. In contrast, convection was not observed at 20 °C even when decoupling was applied.

When the effect from viscosity and convection were both considered, the diffusion coefficients of the lipid-free and lipid-containing αS samples were (8.60 ± 0.19) × 10–11 and (7.94 ± 0.14) × 10–11 m2 s–1, respectively. Because the diffusion measurements were performed on alpha protons, we assume that the measured coefficients are not influenced by amide-water proton exchange even at pH 7.4 and 35 °C.

DISCUSSION [I AM ADDRESSING THESE REVISIONS IN THE OTHER UPDATED DISCUSSIONFILE]

Under physiological conditions, fast proton chemical exchange during gradient-encoding, diffusion, gradient-decoding and frequency-labeling periods can lead to a complete loss of 1HN-DOSY signals. The 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC signal is not affected by proton chemical exchange during the first three periods, whereas 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC is not affected by chemical exchange during all periods.

Another high-resolution DOSY scheme that is relatively insensitive to amide-water proton exchange is worth mentioning. Initially, multidimensional diffusion experiments were designed to evolve the 15N chemical shifts during the diffusion delay.20,25 The experiments were further developed to measure diffusion of large proteins by storing the gradient-encoded magnetization in the Nz state, because 15N has a longer T1 relaxation time than 1H. This experiment called heteronuclear stimulated echoes (X-STE)61 was modified to obtain 15N-chemical-shift information during the diffusion delay24 and was also optimized for transverse relaxation.62

Nz magnetization is not susceptible to amide-water proton exchange. Thus, during the diffusion delay, the X-STE signal will not decrease because of proton exchange. However, at least for the purpose of diffusion measurements at physiological conditions, we believe that our proposed method will show better performance because of the following reasons. First, the proposed method is not susceptible to proton exchange during the gradient encoding and decoding periods. Second, our method can be easily modified to include the convection-compensation scheme, which is necessary to check for the presence of convection at high (>30 °C) temperatures. Finally, under near physiological conditions of pH 7.4 and 35 °C DOSY signals can be completely lost even in the 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC experiment (Figure 1b), thereby requiring the use of the 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC experiment. We compared the performance of different high-resolution DOSY experiments in Figure S3 using the RKY*Y*KR peptide sample. The X-STE experiment shows superior sensitivity at 5 °C, where the solvent exchange is slow, whereas only the 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC signal was detected at 37 °C, where the solvent exchange is fast.

Because methyl protons provide good sensitivity and do not exchange with solvent, they are an attractive diffusion probe. However, resolution of 1H-13C correlations may not be enough to discriminate multiple coexisting species in a sample, especially for disordered proteins. In a sample that contains αS and SH3, there are three different species; αS, the folded and unfolded states of SH3. Assume that we are interested in simultaneously determining the diffusion rates of αS and the unfolded state of SH3. The amide 1H-15N correlations were generally well-resolved (Figure 6a), where the diffusion rate of each peak can be separately measured and averaged for different species, while the methyl 1H-13C correlations of alanine residues significantly overlapped among each other, even with the constant-time evolution period of 53 ms in the 1H-13C HSQC experiment (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the resolution provided by the amide 1H-15N and methyl 1H-13C correlations of alanine residues in a mixture of proteins. 2D NMR spectra were separately obtained for 0.5 mM αS and 0.2 mM SH3 samples both at pH 6.0 and 20 °C and overlaid. (a) Overlay of the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra. The folded (gray) and unfolded (blue) state of SH3, and αS (red) are shown in different colors. (b) Overlay of the double constant-time (53ms) 1H-13C HSQC spectra for the unfolded (blue) state of SH3 and αS (red). Only the alanine methyl 1H-13C correlations are shown that are expected to have good resolution among methyl groups.

As mentioned, when proton exchange is too fast for frequency labeling by the 1H/15N-HSQC, we used 13C’ detection after the diffusion measurement on 1Hα (i.e., 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC). Nonetheless, the 1Hα-DOSY-1H/15N-HSQC is more sensitive than the 1Hα-DOSY-13C’/15N-HSQC when amide-water proton exchange is reasonably slow, because the NMR signal intensity is proportional to the gyromagnetic ratio of the nucleus and the design of the probe is usually optimized for 1H detection. Thus, the choice of which experiment to use depends on experimental conditions.

In summary, we presented an NMR method that can measure the diffusion of proteins at high resolution under physiological conditions. By separating the nuclei used for diffusion (1Hα) and those used for detection (1H/15N and 13C’/15N correlations), the method can simultaneously determine the diffusion rates of coexisting species without artifacts from amide-water proton exchange. As more research focuses on studying biomolecules under physiological conditions in the milieu of biomolecular mixtures, we believe that the high-resolution DOSY experiments presented herein will become increasingly useful.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Dr. Yoon-Joo Ko of the National Center for Inter-University Research Facilities (NCIRF) at Seoul National University (SNU) for NMR assistance. This work was supported by the Creative-pioneering researchers program through SNU, a grant from the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea (No. 2019R1C1C1009685) and a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM125995-01) to SC.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

Full description of NMR pulse sequences; Procedures for preparing NMR samples; Assignment of SH3 backbone resonances

REFERENCES

- (1).Varela AE; Lang JF; Wu Y; Dalphin MD; Stangl AJ; Okuno Y; Cavagnero SJ Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 7682–7698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wang Y; Sarkar M; Smith AE; Krois AS; Pielak GJ J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 16614–16618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Taylor GI Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 1953, 219, 186–203. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Berne BJ; Pecora R, Dynamic light scattering: with applications to chemistry, biology, and physics. Wiley: New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Krichevsky O; Bonnet G Rep. Prog. Phys 2002, 65, 251. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Yildiz A; Forkey JN; McKinney SA; Ha T; Goldman YE; Selvin PR Science 2003, 300, 2061–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Stejskal EO; Tanner JE J. Chem. Phys 1965, 42, 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Price WS, NMR studies of translational motion: principles and applications. Cambridge University Press: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Johnson CS Jr Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc 1999, 34, 203–256. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Cohen Y; Avram L; Frish L Angew. Chem 2005, 44, 520–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Morris KF; Johnson CS Jr J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 3139–3141. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Evans R; Deng Z; Rogerson AK; McLachlan AS; Richards JJ; Nilsson M; Morris GA Angew. Chem 2013, 52, 3199–3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Wu D; Chen A; Johnson CS Jr J. Magn. Reson 1996, 121, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Birlirakis N; Guittet EJ Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 13083–13084. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Gozansky EK; Gorenstein DG J. Magn. Reson 1996, 111, 94–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Rajagopalan S; Chow C; Raghunathan V; Fry CG; Cavagnero SJ Biomol. NMR 2004, 29, 505–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Williamson RT; Chapin EL; Carr AW; Gilbert JR; Graupner PR; Lewer P; McKamey P; Carney JR; Gerwick WH Org. Lett 2000, 2, 289–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Shukla M; Dorai KJ Magn. Reson 2011, 213, 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Barjat H; Morris GA; Swanson AG J. Magn. Reson 1998, 131, 131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Orekhov VY; Korzhnev DM; Pervushin KV; Hoffmann E; Arseniev AS J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn 1999, 17, 157–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Buevich AV; Baum JJ Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 7156–7162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Andrec M; Prestegard JH J. Biomol. NMR 1997, 9, 136–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Brand T; Cabrita EJ; Morris GA; Günther R; Hofmann H-J; Berger SJ Magn. Reson 2007, 187, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Augustyniak R; Ferrage F; Paquin R; Lequin O; Bodenhausen GJ Biomol. NMR 2011, 50, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Choy W-Y; Mulder FA; Crowhurst KA; Muhandiram D; Millett IS; Doniach S; Forman-Kay JD; Kay LE J. Mol. Biol 2002, 316, 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Pervushin K; Vögeli B; Eletsky AJ Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 12898–12902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Yao S; Meikle TG; Sethi A; Separovic F; Babon JJ; Keizer DW Eur. Biophys. J 2018, 47, 891–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Gil S; Hošek T; Solyom Z; Kümmerle R; Brutscher B; Pierattelli R; Felli IC Angew. Chem 2013, 52, 11808–11812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lee JH; Zhang D; Hughes C; Okuno Y; Sekhar A; Cavagnero S Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2015, 112, E4206–E4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Delaglio F; Grzesiek S; Vuister GW; Zhu G; Pfeifer J; Bax AJ Biomol. NMR 1995, 6, 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lee W; Tonelli M; Markley JL Bioinformatics 2014, 31, 1325–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Geen H; Freeman RJ Magn. Reson 1991, 93, 93–141. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Emsley L; Bodenhausen G Chem. Phys. Lett 1990, 165, 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Longsworth LJ Phys. Chem 1960, 64, 1914–1917. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Nietlispach D; Ito Y; Laue ED J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 11199–11207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Brutscher BJ Magn. Reson 2002, 156, 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Permi PJ Biomol. NMR 2002, 23, 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Tanner JE J. Chem. Phys 1970, 52, 2523–2526. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wu D; Chen A; Johnson CS J. Magn. Reson 1995, 115, 260–264. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Pelta MD; Morris GA; Stchedroff MJ; Hammond SJ Magn. Reson. Chem 2002, 40, S147–S152. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Ying J; Chill JH; Louis JM; Bax AJ Biomol. NMR 2007, 37, 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Kay L; Keifer P; Saarinen TJ Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Marion D; Ikura M; Tschudin R; Bax AJ Magn. Reson 1989, 85, 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Jerschow A; Müller NJ Magn. Reson 1997, 125, 372–375. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Loening NM; Keeler JJ Magn. Reson 1999, 139, 334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Sinnaeve D Concepts Magn. Reson. Part A 2012, 40, 39–65. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Chou JJ; Baber JL; Bax AJ Biomol. NMR 2004, 29, 299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Zhang O; Kay LE; Olivier JP; Forman-Kay JD J. Biomol. NMR 1994, 4, 845–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Farrow NA; Zhang O; Forman-Kay JD; Kay LE J. Biomol. NMR 1994, 4, 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Tollinger M; Skrynnikov NR; Mulder FA; Forman-Kay JD; Kay LE J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 11341–11352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Wilke CR; Chang P AIChE J. 1955, 1, 264–270. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Hayduk W; Laudie H AIChE J. 1974, 20, 611–615. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Li J; Carr PW Anal. Chem 1997, 69, 2530–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Iwai A; Masliah E; Yoshimoto M; Ge N; Flanagan L; De Silva HR; Kittel A; Saitoh T Neuron 1995, 14, 467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Bodner CR; Dobson CM; Bax AJ Mol. Biol 2009, 390, 775–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Eliezer D; Kutluay E; Bussell R Jr; Browne GJ Mol. Biol 2001, 307, 1061–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Burré J; Sharma M; Tsetsenis T; Buchman V; Etherton MR; Südhof TC Science 2010, 329, 1663–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Galvagnion C; Buell AK; Meisl G; Michaels TC; Vendruscolo M; Knowles TP; Dobson CM Nat. Chem. Biol 2015, 11, 229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Rhoades E; Ramlall TF; Webb WW; Eliezer D Biophys. J 2006, 90, 4692–4700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Wang Y; Li C; Pielak GJ J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 9392–9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Ferrage F; Zoonens M; Warschawski DE; Popot J-L; Bodenhausen GJ Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 2541–2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Horst R; Horwich AL; Wüthrich K J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 16354–16357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.