Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a worldwide public health problem. Here, a bibliometric analysis is performed to evaluate the publications in the Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) field from 2000 to 2019 based on the Science Citation Index (SCI) Expanded and the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) databases. This work presents a detailed overview of IPV from aspects of types of articles, citations, h-indices, languages, years, journals, institutions, countries, and author keywords. The results show that the USA takes the leading position in this research field, followed by Canada and the U.K. The University of North Carolina has the most publications and Harvard University has the first place in terms of h-index. The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine leads the list of average citations per paper. The Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Journal of Family Violence and Violence Against Women are the top three most productive journals in this field, and Psychology is the most frequently used subject category. Keywords analysis indicates that, in recent years, most research focuses on the research fields of “child abuse”, “pregnancy”, “HIV”, “dating violence”, “gender-based violence” and “adolescents”.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, HIV, violence, bibilometric, keywords analysis

1. Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a common and worldwide health concern [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), IPV includes “any behavior by an intimate partner or ex-partner that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including acts of physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviors” [9]. According to a WHO report in 2013 [10], over one in three women worldwide have experienced physical and/or sexual partner violence, or sexual violence by a non-partner. IPV levels vary in different regions due to a variety of cultural, economic level, social system, and religious reasons, with the highest prevalence in Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean and the South–East Asia Regions, followed by the Americas. High-income regions, the European and the Western Pacific Regions have a relatively low prevalence [10]. Since IPV is associated with many serious physical and mental health consequences: physical injury [11,12,13,14], post-traumatic stress disorder [15,16,17], HIV infections [18,19,20,21], induced abortion [22,23,24], alcohol use disorders [25,26,27,28,29], adolescent pregnancy [30,31,32,33], dating violence [30,34,35,36,37], and more, scholars from many countries have been participating in the study of IPV and how to prevent the violence [38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

According to the literature, America is the earliest region to study IPV. E.J. Alpert. proposed in 1995 that physicians can play an important role in the early intervention of IPV through querying women who were treated for emergency care [45]. Over the ensuing few years, many strategies were proposed to prevent IPV, such as training programs [46], abuse screening [7,38,40], and reducing poverty and alcohol consumption [41]. Since the WHO released the “World report on violence and health” in 2002, more and more countries joined the IPV research. The collaborations between regions or countries also are increasing.

Recently, bibliometric analysis has been an effective tool to quantitatively analyze academic publications to evaluate the research trends in different research fields, such as health care science services [47,48,49,50,51], Psychology [52,53], Economics [54,55], Energy [11,51,56,57] and Ecology [58,59]. Bibliometrics, first proposed by Alan Pritchard in a paper in 1969, is defined as “the application of mathematics and statistical methods to books and other media of communication” [60]. To our knowledge, this is the first time assessing the IPV research field using bibliometric methods. The aim of this research is to provide a broad overview on the IPV research area, including the following aspects: (1) the main contributors: country, institute, research group; (2) collaboration patterns: cooperation between countries; (3) the most productive journals; (4) top papers with highest citation numbers; (5) research trends by analyzing the author keywords. This study demonstrates the research focuses and hotspots of IPV research, which enable readers to understand the trajectories, key elements on the theoretical and practical contributions, and the future challenges of IPV.

2. Methods

The analysis was based on the papers related to “Intimate Partner Violence” which were obtained from the Science Citation Index-Expanded (SCI-E) and Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) during the period from 2000 to 2019. The data was retrieved through the “Web of Science Core collection” by searching the title, abstract, author keywords and KeyWords plus with the search formula of “Intimate partner violence” or “Intimate partner abuse” or “spous* violence” or “spous* abuse” or “wife violence” or “wife abuse” or “husband violence” or “husband abuse” on 20 July 2020. The data of the top 25 authors in “Intimate Partner Violence” and citation analyses were acquired on 20 July 2020. Keywords and international cooperation were analyzed using the Derwent Data Analyzer (DDA) software. The Impact Factor (IF) for each journal was determined according to the report from the 2019 Journal Citation Reports (JCR). Note that some related publications that do not use the above search formula may not be included in this analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Number and Types of Publications

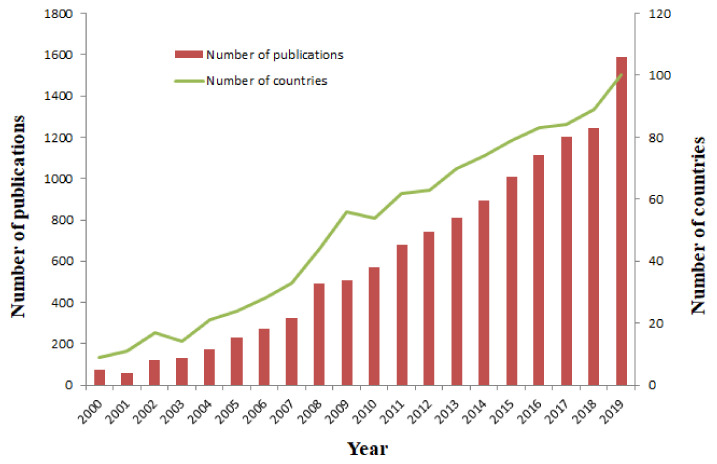

All told, 13,515 papers met the search criteria mentioned above, including 13 article types. They were: articles (11,450), reviews (925), meeting abstracts (550), editorial materials (333), proceedings papers (278), early access (188), letters (94), corrections (41), book reviews (32), book chapters (19), news items (9), reprints (4) and a retracted publication (1). The vast majority of articles and reviews were published in English (12,044; 97.325%), followed by Spanish (180; 1.445%), Portuguese (65; 0.525%), German (32; 0.259%), French (20; 0.162%), Turkish (14; 0.113%), Slovenian (6; 0.048%), Italian (4; 0.032%), Croatian (4; 0.032%), Polish (2; 0.016%), Korean (1; 0.008%), Afrikaans (1; 0.008%) and Hungarian (1; 0.008%). The following analysis was only based on the articles and reviews which were the majority of the publications in this field. Figure 1 shows the annual analysis of published papers and the number of countries. It is clear that the number of annual publications and countries have been increasing at a relatively high rate since 2002. This is attributed possibly to the report from the WHO [9]. Until 2019, 151 countries or regions have participated in IPV research.

Figure 1.

The number of the publication and number of countries by year.

The top 30 most productive countries in the IPV research field are shown in Table 1. The USA led the list with the most publications (7947) and highest h-index (149). Canada was in the second position, but the amount of publications is only 12% of that from the USA. Other productive countries include the UK (899), Australia (631), Spain (554), South Africa (513), and Sweden (352). Switzerland took the first position of average citations per paper (71.73). The UK is listed in the second position (29.72), followed by South Africa (29.04), Uganda (24.39), the USA (24.19), India (23.29) and Bangladesh (22.06).

Table 1.

Contribution and impact of the top 30 most productive countries in Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) research.

| Rank | Country | TP | TC | ACCP | h-Index | SP (%) | nCC | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 7947 | 196,711 | 24.75 | 149 | 19.51 | 119 | Americas |

| 2 | Canada | 971 | 19,666 | 20.25 | 65 | 44.28 | 72 | Americas |

| 3 | UK | 899 | 26,718 | 29.72 | 71 | 61.07 | 90 | Europe |

| 4 | Australia | 631 | 11,555 | 18.31 | 45 | 46.59 | 65 | Oceania |

| 5 | Spain | 554 | 5756 | 10.39 | 34 | 30.69 | 46 | Europe |

| 6 | South Africa | 513 | 14,896 | 29.04 | 54 | 71.73 | 60 | Africa |

| 7 | Sweden | 352 | 5367 | 15.25 | 33 | 56.25 | 60 | Europe |

| 8 | P.R. China | 220 | 3081 | 14.00 | 29 | 50.91 | 35 | Asia |

| 9 | Brazil | 218 | 2901 | 13.31 | 25 | 33.94 | 29 | Americas |

| 10 | India | 200 | 4658 | 23.29 | 37 | 74.50 | 30 | Asia |

| 11 | Netherlands | 181 | 2970 | 16.41 | 26 | 48.62 | 35 | Europe |

| 12 | Israel | 166 | 2402 | 14.47 | 25 | 35.54 | 23 | Asia |

| 13 | Germany | 159 | 2431 | 15.29 | 23 | 65.41 | 45 | Europe |

| 14 | Norway | 127 | 2136 | 16.82 | 23 | 55.12 | 37 | Europe |

| 15 | Switzerland | 120 | 8608 | 71.73 | 36 | 84.17 | 47 | Europe |

| 16 | Italy | 117 | 1460 | 12.48 | 19 | 61.54 | 43 | Europe |

| 17 | New Zealand | 104 | 2017 | 19.34 | 24 | 36.54 | 19 | Oceania |

| 18 | Uganda | 103 | 2512 | 24.39 | 25 | 95.14 | 26 | Africa |

| 19 | Turkey | 102 | 809 | 7.93 | 15 | 17.65 | 8 | Asia |

| 20 | Kenya | 96 | 1536 | 16.00 | 20 | 96.88 | 29 | Africa |

| 21 | Mexico | 95 | 1188 | 12.51 | 19 | 69.47 | 19 | Americas |

| 22 | South Korea | 87 | 687 | 7.90 | 14 | 56.32 | 9 | Asia |

| 23 | Bangladesh | 85 | 1875 | 22.06 | 21 | 81.18 | 17 | Asia |

| 24 | Japan | 79 | 899 | 11.38 | 15 | 48.10 | 18 | Asia |

| 25 | Nigeria | 75 | 1115 | 14.87 | 19 | 58.67 | 30 | Africa |

| 26 | Tanzania | 70 | 858 | 12.26 | 18 | 92.86 | 28 | Africa |

| 27 | Portugal | 67 | 525 | 7.84 | 12 | 46.27 | 21 | Europe |

| 28 | Ethiopia | 64 | 861 | 13.45 | 17 | 65.08 | 25 | Africa |

| 29 | Belgium | 56 | 949 | 16.95 | 16 | 62.50 | 35 | Europe |

| 30 | Chile | 52 | 524 | 10.08 | 13 | 82.69 | 20 | Americas |

Note: TP total paper, TC total citations, ACCP average citations per paper, SP Share of publications. nCC number of cooperative countries or regions.

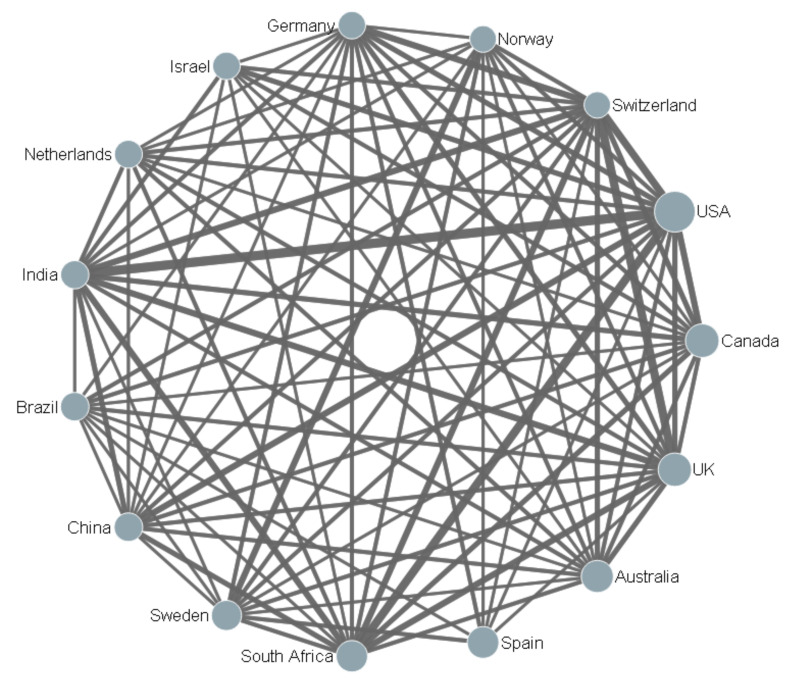

3.2. Cooperation of Countries

Shown in Table 1, all the countries from Africa had a very high share of internationally collaborative papers, especially Kenya and Uganda. Ten European countries held a relatively high share of cooperative publications. Especially, Switzerland had an 84.17% share of co-author papers with other countries or regions. It is worth mentioning that, although the USA was the most active country—collaborating with 119 other countries or regions—over 80% of the papers published independently were from the USA. Altogether, most productive countries had frequent cooperation with other countries or regions.

The academic collaboration network of the top 15 most productive countries is shown in Figure 2. Derwent Data Analyzer (DDA) software was applied to draw the network diagram on the basis of a co-occurrence matrix. The size of the nodes is according to the number of publications and the thickness of the connecting lines represent the frequency of cooperation. It is clearly demonstrated that the USA cooperated most frequently with South Africa, India, the UK, and Switzerland with strong collaboration relationships. Furthermore, the USA, the UK, Australia, South Africa, Germany, and Switzerland had the biggest collaboration network within the top 15 most productive countries.

Figure 2.

Collaborative relationships among the top 15 most productive countries.

3.3. Contribution of Leading Institutes

A total of 6684 institutes have participated in the study of IPV. The top 20 productive institutes, which were from the top four most productive countries, are shown in Table 2. Among them, seventeen institutes are located in the USA, one in the Canada, the UK and Australia respectively, which indicates again that the USA dominates the IPV research area. The University of North Carolina ranks first in terms of total publications, followed by Johns Hopkins University and the University of Michigan. The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine holds the first position for average citations per paper (ACCP). Harvard University has the highest h-index value. It is worth noting that there is no institute from Asia, Africa or Oceania on this list. We expect more countries will increase their funding input and strengthen international and domestic cooperation to prevent IPV.

Table 2.

The Top 20 most productive institutions for publications, citations, and h-indices during 2000–2019.

| Institutions | TP | TC | ACCP | h-Index | SP (%) | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of North Carolina | 348 | 11,970 | 34.40 | 55 | 75.29 | USA |

| Johns Hopkins University | 337 | 13,427 | 39.84 | 59 | 89.61 | USA |

| University of Michigan | 295 | 6361 | 21.41 | 37 | 81.02 | USA |

| Columbia University | 282 | 7158 | 25.38 | 45 | 90.07 | USA |

| Boston University | 281 | 9225 | 32.83 | 52 | 93.95 | USA |

| Emory University | 280 | 7420 | 26.50 | 40 | 82.86 | USA |

| Harvard University | 260 | 13,425 | 51.63 | 60 | 98.85 | USA |

| University of Washington | 250 | 8112 | 32.45 | 48 | 84.40 | USA |

| University of California San Francisco | 228 | 5567 | 24.42 | 38 | 90.79 | USA |

| University of Toronto | 223 | 4882 | 21.89 | 35 | 90.58 | Canada |

| Yale University | 215 | 4146 | 19.28 | 34 | 85.58 | USA |

| Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health | 192 | 4084 | 21.27 | 34 | 91.67 | USA |

| London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine | 190 | 10,575 | 55.66 | 45 | 92.11 | UK |

| Michigan State University | 188 | 3574 | 19.01 | 31 | 65.96 | USA |

| University of Pittsburgh | 174 | 3868 | 22.23 | 36 | 87.93 | USA |

| Ctr Dis Control & Prevent | 171 | 6772 | 39.60 | 35 | 69.01 | USA |

| University of California San Diego | 171 | 4643 | 27.15 | 36 | 98.83 | USA |

| University of Pennsylvania | 168 | 3553 | 21.15 | 32 | 86.31 | USA |

| University of Illinois | 161 | 3241 | 20.13 | 32 | 76.40 | USA |

| University of Melbourne | 157 | 2889 | 18.40 | 28 | 87.90 | Australia |

Note: TP total paper, TPR% the percentage of articles or journals in total publications, TC total citations, ACCP average citations per paper, SP Share of publications.

Additionally, we analyzed the share of cooperative publications between institutes (see Table 2). It can be seen that all 20 of the most productive institutions have very high collaboration rates, especially the University of California-San Diego and Harvard University. It suggests that IPV research requires the cooperation of multiple institutions such as: universities, hospitals, and sectors of government and non-government.

3.4. Contribution of Leading Authors

The top 25 most productive authors are shown in Table 3, based on the number of publications. J.C. Campbell led the list with 151 papers followed by J.G. Silverman (94) and G.L. Stuart. (87). Regarding the average citation per paper, C. Watts ranked first with 71.92 followed by R. Caetano (64.27), and R. Jewkes (62.19). The highest h-index was achieved by J.C. Campbell (43). Among these top 25 productive authors, 18 authors were in the USA, two in the UK and Spain, and one in Canada, South Africa, and Australia, respectively.

Table 3.

Contribution of the top 25 authors in IPV research.

| Rank | Author | TP | TPR% | TC | ACCP | h-Index | Institute (Current), Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Campbell, J.C. | 151 | 1.233 | 8310 | 55.03 | 41 | Johns Hopkins University, USA |

| 2 | Silverman, J.G. | 94 | 0.768 | 4983 | 53.01 | 36 | Harvard University, USA |

| 3 | Stuart, G.L. | 87 | 0.710 | 2615 | 30.06 | 28 | The University of Tennessee, USA |

| 4 | Decker, M.R. | 86 | 0.702 | 3751 | 43.62 | 35 | Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, USA |

| 5 | Jewkes, R. | 79 | 0.645 | 4913 | 62.19 | 30 | South African Medical Research Council, South Africa |

| 6 | Raj, A. | 78 | 0.637 | 3978 | 51.00 | 32 | University of California San Diego, USA |

| 7 | Miller, E. | 71 | 0.580 | 2037 | 28.69 | 25 | University of Pittsburgh, USA |

| 8 | Vives-Cases, C. | 64 | 0.523 | 728 | 11.38 | 14 | University of Alicante, Spain |

| 9 | Shorey, R. C. | 62 | 0.506 | 1261 | 20.34 | 17 | Ohio University, USA |

| 10 | O’Campo, R. | 61 | 0.498 | 2665 | 42.98 | 26 | St Michaels Hospital, Toronto, Canada |

| 11 | Watts, C. | 60 | 0.490 | 4315 | 71.92 | 30 | London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK |

| 12 | Caetano, R. | 59 | 0.482 | 3792 | 64.27 | 36 | Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, USA |

| 13 | Feder, G | 56 | 0.457 | 1862 | 33.25 | 20 | University of Bristol, UK |

| 14 | Graham-Bermann, S.A. | 55 | 0.449 | 1055 | 19.18 | 18 | University of Michigan, USA |

| 15 | Yount, K.M. | 55 | 0.449 | 843 | 15.33 | 19 | Emory University, USA |

| 16 | Cerulli, C. | 54 | 0.441 | 904 | 16.74 | 15 | University of Rochester, USA |

| 17 | El-Bassel, N. | 54 | 0.441 | 1484 | 27.48 | 21 | Columbia University, USA |

| 18 | Lila, M. | 53 | 0.433 | 737 | 13.91 | 17 | University of Valencia, Spain |

| 19 | McFarlane, J. | 53 | 0.433 | 862 | 16.26 | 13 | Texas Woman’s University, USA |

| 20 | Glass, N. | 52 | 0.425 | 1463 | 28.13 | 17 | Johns Hopkins, USA |

| 21 | Hegarty, K | 52 | 0.425 | 1126 | 21.65 | 16 | University of Melbourne, Australia |

| 22 | Stephenson, R | 51 | 0.416 | 1144 | 22.43 | 17 | University of Michigan, USA |

| 23 | Kaslow, N.J. | 50 | 0.408 | 1391 | 27.82 | 21 | Emory University, USA |

| 24 | Gilbert, L | 48 | 0.392 | 1450 | 30.21 | 20 | Columbia University, USA |

| 25 | Sullivan, T.P. | 47 | 0.384 | 687 | 14.62 | 14 | Yale University, USA |

Note: TP total paper, TPR% the percentage of articles of journals in total publications, TC total citations, ACCP average citations per paper.

3.5. Contribution of Leading Research Areas and Journals

Twelve thousand three hundred and seventy-five papers related to IPV have been published in about 103 research areas in SCI and SSCI databases, among which the top 20 are listed in Table 4. ‘Psychology’ ranked in the first position in terms of the total publications and h-index, followed by ‘Family Studies’, Public Environmental Occupational Health’ and ‘Criminology Penology’. ‘General Internal Medicine’ led the list of the ACCP (45.38), followed by ‘Neurosciences Neurology’, and ‘Pediatrics’.

Table 4.

Contribution of the Top 20 research areas in IPV research.

| Research Areas | TP | TC | ACCP | h-Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychology | 4262 | 83,592 | 19.61 | 105 |

| Family Studies | 2670 | 50,493 | 18.91 | 87 |

| Public Environmental Occupational Health | 2608 | 61,018 | 23.40 | 102 |

| Criminology Penology | 2253 | 40,510 | 17.98 | 81 |

| Women’s Studies | 1182 | 21,812 | 18.45 | 62 |

| Psychiatry | 1159 | 22,239 | 19.19 | 66 |

| Social Work | 911 | 17,614 | 19.33 | 65 |

| General Internal Medicine | 837 | 37,983 | 45.38 | 87 |

| Nursing | 581 | 6289 | 10.82 | 35 |

| Obstetrics Gynecology | 569 | 12,284 | 21.59 | 52 |

| Biomedical Social Sciences | 463 | 12,269 | 26.50 | 58 |

| Substance Abuse | 365 | 8983 | 24.61 | 50 |

| Health Care Sciences Services | 361 | 5521 | 15.29 | 37 |

| Pediatrics | 268 | 7243 | 27.03 | 46 |

| Social Sciences Other Topics | 220 | 2897 | 13.17 | 27 |

| Science Technology Other Topics | 219 | 3673 | 16.77 | 32 |

| Infectious Diseases | 198 | 5109 | 25.80 | 39 |

| Neurosciences Neurology | 194 | 6317 | 32.56 | 42 |

| Sociology | 186 | 3459 | 18.60 | 33 |

| Government Law | 180 | 1914 | 10.63 | 23 |

Note: TP total paper, TPR% the percentage of share publications, TC total citations, ACCP average citations per paper.

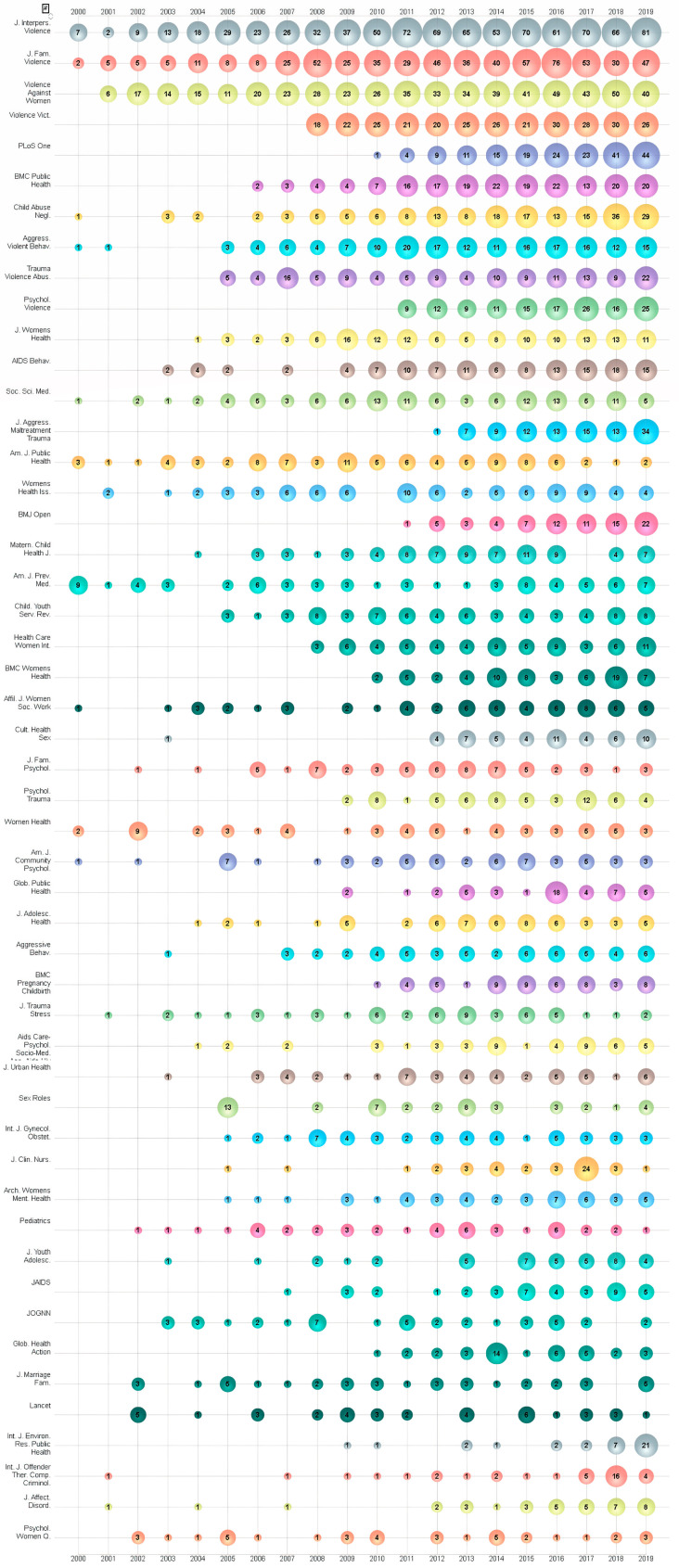

The 12,375 papers related to IPV research during 2000–2019 were published in 1454 journals. The top 50 journals in terms of the number of total publications are shown in Table 5. Approximately 48% of the papers were published in these top 50 productive journals. The top five journals produced 2590 papers with a 21.15% share of the publications. A bubble chart of the top 50 productive journals by year is shown in Figure 3. The Journal of Interpersonal Violence, the Journal of Family Violence and Violence Against Women were the top three most productive journals, with a sharp increase in IPV research outputs during the last decade. It can be clearly seen that there were few articles sparsely distributed in most of the top 50 journals from 2000–2007, however, there has been a rapid growth in publications since 2008. It is clear to see that more and more research workers have contributed to the ‘International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health’. It is worth noting that Lancet (IF = 60.392), one of the most authoritative academic journals in the world medical community and one of the most influential SCI journals, is in the 46th position on the list. This suggests that IPV is a popular and important research area.

Table 5.

Contribution of the top 50 most productive Journals in IPV research.

| No. | Journal Name | IF2019 | No. | Journal Name | IF2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Journal of Interpersonal Violence | 3.573 | 26 | Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy | 2.595 |

| 2 | Journal of Family Violence | 1.357 | 27 | Women’s Health | 1.095 |

| 3 | Violence against Women | 1.797 | 28 | American Journal of Community Psychology | 1.509 |

| 4 | Violence and Victims | 0.598 | 29 | Global Public Health | 1.791 |

| 5 | Plos One | 2.740 | 30 | Journal of Adolescent Health | 3.900 |

| 6 | BMC Public Health | 2.521 | 31 | Aggressive Behavior | 2.219 |

| 7 | Child Abuse Neglect | 2.569 | 32 | BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth | 2.239 |

| 8 | Aggression and Violent Behavior | 2.893 | 33 | Journal of Traumatic Stress | 1.926 |

| 9 | Trauma Violence Abuse | 6.325 | 34 | Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/HIV | 1.894 |

| 10 | Psychology of Violence | 2.381 | 35 | Journal of Urban Health Bulletin of The New York Academy of Medicine | 2.356 |

| 11 | Journal of Women’s Health | 1.933 | 36 | Sex Roles | 2.409 |

| 12 | Aids and Behavior | 3.147 | 37 | International Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics | 2.216 |

| 13 | Social Science Medicine | 3.616 | 38 | Journal of Clinical Nursing | 1.972 |

| 14 | Journal of Aggression Maltreatment Trauma | 1.030 | 39 | Archives of Women’s Mental Health | 2.500 |

| 15 | American Journal of Public Health | 6.464 | 40 | Pediatrics | 5.359 |

| 16 | Women’s Health Issues | 2.355 | 41 | Journal of Youth and Adolescence | 3.121 |

| 17 | BMJ Open | 2.496 | 42 | Jaids-Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes | 3.475 |

| 18 | Maternal and Child Health Journal | 1.890 | 43 | Jognn Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing | 1.250 |

| 19 | American Journal of Preventive Medicine | 4.420 | 44 | Global Health Action | 2.162 |

| 20 | Children and Youth Services Review | 1.521 | 45 | Journal of Marriage and Family | 2.215 |

| 21 | Health Care for Women International | 0.970 | 46 | Lancet | 60.392 |

| 22 | BMC Women’s Health | 1.544 | 47 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 2.849 |

| 23 | Affilia Journal of Women and Social Work | 1.085 | 48 | International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology | 1.026 |

| 24 | Culture Health Sexuality | 1.969 | 49 | Journal of Affective Disorders | 3.892 |

| 25 | Journal of Family Psychology | 1.840 | 50 | Psychology of Women Quarterly | 2.444 |

Note: IF: impact factor.

Figure 3.

Bubble chart of the Top 50 productive journals by year.

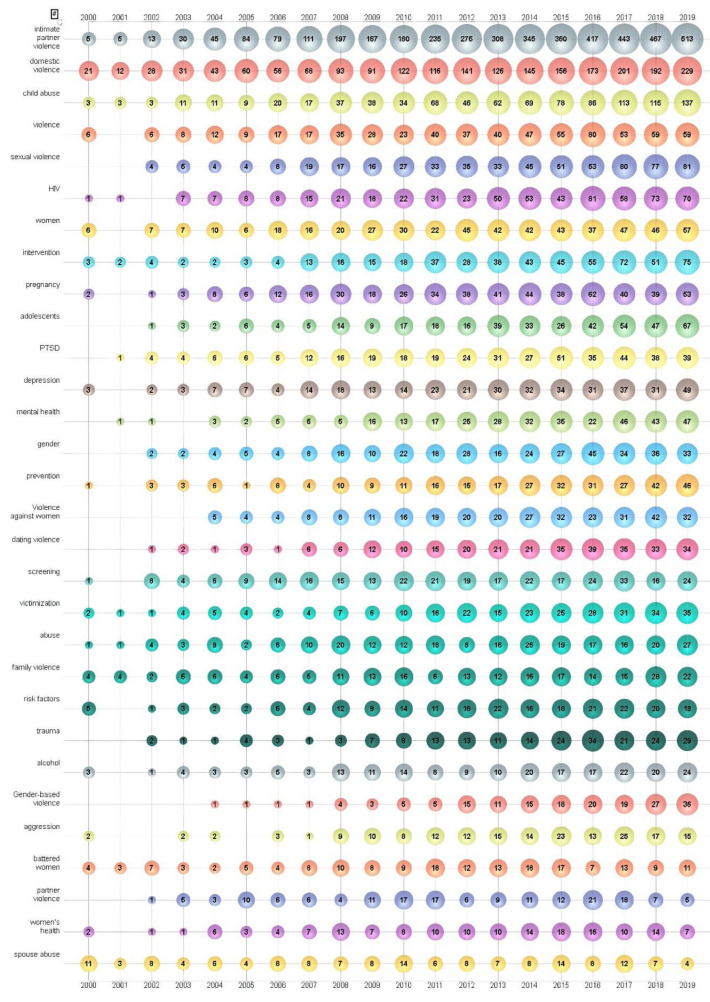

3.6. An Analysis of Keywords

To elucidate the main focus and research trend of IPV research, 10,085 author keywords from 12,375 papers were analyzed. The raw data were cleaned to ensure that keywords with the same meanings were represented by one unified word. Among the author keywords, 6794 (68%) were used only once and 1279 (13%) used twice. However, the top 30 most used author keywords appeared 16,614 (35%) times. The large number of once-only author keywords may indicate a wide range of interests in IPV research. As a bubble chart can clearly express in 3D values, using the bubble size as the third dimension, one can be applied to track research frontiers [51,61,62,63]. The top 30 author keywords by year are shown in Figure 4. Using visual bubble charts, the development trend of research can be clearly presented. Note that the number on the bubble represents author keyword occurrence frequencies and the number of publications.

Figure 4.

Bubble chart of top 30 author keywords by year.

3.7. An Analysis of the Most Cited Papers

Although the citation impact of a paper depends on many factors [64], it is still a measure of its influence in this research field. The top 20 most highly cited publications are presented in Table 6. The most highly cited paper was “Health consequences of intimate partner violence.” published in the Lancet by Campbell, J.C. It led the list of total times cited with 1865 and held the second position for annual citations. “The Epidemiology of Depression Across Cultures” [65], authored by Kessler and Bromet, took the first position for annual citations with 128.00. “Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence” authored by Garcia–Moreno, C., et al., ranked in the third position with annual citations of 106.46.

Table 6.

The Top 20 most cited publications in IPV research field during 2000–2019.

| No | Authors | Title | Total Citation | Citation/Year | Journal/IF2019 | Publication Year | Country (Reprint Address) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Campbell, J.C. | Health consequences of intimate partner violence. | 1865 | 109.71 | Lancet/60.392 | 2002 | USA |

| 2 | Garcia-Moreno, C.; Jansen, H.A.F.M.; Ellsberg, M.; et al. | Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. | 1384 | 106.46 | Lancet/60.392 | 2006 | Switzerland |

| 3 | Archer, J. | Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. | 1350 | 71.05 | Psychological Bulletin/20.850 | 2007 | Canada |

| 4 | Coker, A.L.; Davis, K.E.; Arias, I. | Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. | 1169 | 68.76 | American Journal of Preventive Medicine/4.420 | 2002 | USA |

| 5 | Krug, E.G.; Mercy, J.A.; Dahlberg, L.L.; et al. | The world report on violence and health. | 948 | 55.76 | Lancet/60.392 | 2002 | Switzerland |

| 6 | Ellsberg, M.; Jansen, H.A.F.M.; Heise, L.; et al. | Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: An observational study. | 891 | 81.00 | Lancet/60.392 | 2008 | Switzerland |

| 7 | Jewkes, R. | Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. | 814 | 47.88 | Lancet/60.392 | 2002 | South Africa |

| 8 | Dunkle, K.L; Jewkes, R.K.; Brown, H.C.; et al. | Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. | 797 | 53.13 | Lancet/60.392 | 2004 | South Africa |

| 9 | Kessler, R.C., Bromet, E.J. | The Epidemiology of Depression Across Cultures | 768 | 128.00 | Annual Review of Public Health/16.463 | 2013 | USA |

| 10 | Silverman, J. G., Raj, A., Mucci, L. A.; et al. | Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. | 735 | 40.83 | Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association/45.540 | 2001 | USA |

| 11 | Babcock, J.C.; Green, C.E.; Robie, C. | Does batterers’ treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment | 685 | 45.67 | Clinical Psychology Review/10.225 | 2004 | USA |

| 12 | Jewkes, R.K.; Dunkle, K.; Nduna, M., et al. | Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study. | 659 | 73.22 | Lancet/60.392 | 2010 | South Africa |

| 13 | Shin, L.M.; Rauch, S.L.; Pitman, R.K. | Amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal function in PTSD | 614 | 43.86 | Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences/4.728 | 2005 | USA |

| 14 | Coker, A.L.; Smith, P.H, Bethea, L.; et al. | Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. | 611 | 32.16 | Archives of Family Medicine/2.878 (Year 2002) | 2000 | USA |

| 15 | Tremblay, R.E.; Nagin, D.S.; Seguin, J.R.; et al. | Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors | 570 | 38.00 | Pediatrics/5.359 | 2004 | Canada |

| 16 | Holt, S., Buckley, H., Whelan, S. | The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. | 561 | 51.00 | Child Abuse & Neglect/2.569 | 2008 | Ireland |

| 17 | Stith, S.M.; Smith, D.B.; Penn, C.E. | Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review | 556 | 37.07 | Aggression and Violent Behavior/2.893 | 2004 | USA |

| 18 | Campbell, J.; Jones, A.S.; Dienemann, J.; et al. | Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. | 536 | 31.53 | Archives of Internal Medicine/17.333 (Year 2014) | 2002 | USA |

| 19 | Fisher, J.; de Mello, M.C.; Patel, V.; et al. | Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review. | 526 | 75.14 | Bulletin of The World Health Organization/6.960 | 2012 | Australia |

| 20 | Pronyk, P.M.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Kim, J.C.; et al. | Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. | 521 | 40.08 | Lancet/60.392 | 2006 | South Africa |

Note: Total Citation/Year: Total Citation/ (2019-Publication Year).

Among these top 20 papers, eight were published in Lancet, and one in Psychological Bulletin, the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, the Annual Review of Public Health, Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association, the Clinical Psychology Review, the Archives of Family Medicine, the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Pediatrics, Child Abuse and Neglect, Aggression and Violent Behavior, the Archives of Internal Medicine, and the Bulletin of The World Health Organization, respectively. The USA contributed nine of them, followed by South Africa (4), Switzerland (3) Canada (2), Australia (1) and Ireland (1), and again indicated that the USA was the leading country in this research field. It is worth noting that three papers from South Africa were related to the study of the relationships between IPV and HIV infection and prevention in South Africa. Through analyzing the publications about IPV, we found that 1547 papers were associated with HIV research and a 34% share of the publications was related to Africa. It suggested that more and more scholars agree that HIV and IPV are related to some extent [19,21,66,67,68].

4. Discussion

One hundred and fifty-one countries contributed 12,357 publications to Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) research from 2000 to 2019, indicating that IPV is a global public health problem and attracting worldwide attention. It is clear that the number of publications has increased steadily since the WHO released the first World Report on Violence and Health in 2002. The number of papers from 2010–2019 was 9884, which represented 80% of the total number of publications. Also, the number of countries which were involved in IPV research increased every year, except for several fluctuations, which indicates that more and more countries have put their efforts to study and prevent IPV.

North America, Western Europe, and Australia were the most active regions in the research of IPV. This was further confirmed by the most active institutions and authors. There was no institute from Asia and Africa in the top 20 most productive institutions. China and India, as the world’s most populous countries, had very low productivity. One possible reason might be the traditional culture difference, funding input, and economic level. Another possible reason is that while the WoS database is comprehensive, some journals published from India, China, and other Asian and African countries are not indexed in WoS. Furthermore, as most SCI papers are published in English, some non-native English-speaking researchers might not produce high quality papers due to the language problem to some extent. These thoughts might explain the low productivity from Asia and Africa.

The obvious change in the number on the bubble of the author keywords showed the trend of IPV research: “intimate partner violence” (4399 times) was the most frequently used keyword and increased sharply during the last ten years (2008–2019), followed by “domestic violence” (2166 times), “child abuse” (985 times), “violence” (650 times), “sexual violence” (611 times), and “HIV/AIDs” (605 times). It is worth mentioning that, among the top 30 author keywords, five were related to “woman”, including “women”, “pregnancy” “violence against women”, “battered women” and “women’s health” and two were related to adolescents and children, including “adolescents” and “child abuse”, which indicates that the biggest victims of IPV are women and children. Studies on the impact of children and young adolescent’s exposure to IPV have attracted great attention from the scholars over the last two decades [33,34,36,69,70]. This trend reflects on the one-in-four of the total 12,357 papers being related to children. Additionally, “child abuse” “pregnancy”, “HIV”, “dating violence”, “gender-based violence” and “adolescents” were used at a very low frequency during 2000–2007 but increased rapidly during the last decade, which might be the new emerging research direction.

The top 20 cited publications are shown in Table 6. The article with the highest citation was a review article published in 2002 and discussed the increased health problems caused by IPV [14]. Overall, five papers were published in 2002. Therefore, 2002 was a milestone year in IPV research. The article “The world report on violence and health” analyzed and summarized the main points of the first report on violence and health released by the WHO in 2002 [4]. “Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence” was published in Lancet in 2006 and discussed the prevalence of IPV in 10 mainly low and middle-income countries [5]. The report, “Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence”, was released by the WHO in 2013 and demonstrated that 30% of all women from over 80 countries have experienced violence by an intimate partner [10]. The WHO, with other agencies, launched a RESPECT women program to prevent violence against women in 2019 [71].

5. Conclusions

Here, we presented a general overview of the Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) research area in terms of leading countries, institutes, and research trends. The USA definitely led IPV research with the most publications and highest h-index. There was no doubt that more and more countries have been participating in IPV research. Since IPV is a world health issue, we expect that, as more and more researchers join this research area, more results will be published based on the collaboration between different research groups all over the world, which will continue to make an effort to stop or prevent IPV. Needless to say, how to prevent IPV more effectively is still a big challenge, although many scholars have made various suggestions to intervene or stop IPV. Furthermore, more and more researchers have recognized that IPV is associated with women’s vulnerability to HIV. We expect more research will focus on these areas.

This study can help potential researchers to quickly understand IPV globally. It also can provide useful information for relevant research in terms of identifying the research trends and potential collaborators, for example. Additionally, this study can help policy makers improve policymaking to prevent IPV.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Y.W. (Yuehua Wan) designed the study. J.C. and H.F. responsible for data collection. Y.W. (Yanqi Wu) analyzed, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Humanity and Social Science Project of Zhejiang Education Department (Y201738172) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LS18G03012).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tang C.S.K., Lai B.P.Y. A review of empirical literature on the prevalence and risk markers of male-on-female intimate partner violence in contemporary China, 1987–2006. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2008;13:10–28. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2007.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soleymani S., Britt E., Wallace-Bell M. Motivational interviewing for enhancing engagement in Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) treatment: A review of the literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018;40:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watts C., Zimmerman C. Violence against women: Global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002;359:1232–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krug E.G., Mercy J.A., Dahlberg L.L., Zwi A.B. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Moreno C., Jansen H., Ellsberg M., Heise L., Watts C.H., Wo W.H.O.M.-C.S. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellsberg M., Jansen H., Heise L., Watts C.H., Garcia-Moreno C., Hlth W.H.O.M.S.W. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: An observational study. Lancet. 2008;371:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coker A.L., Smith P.H., Bethea L., King M.R., McKeown R.E. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch. Fam. Med. 2000;9:451–457. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell J., Jones A.S., Dienemann J., Kub J., Schollenberger J., O’Campo P., Gielen A.C., Wynne C. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002;162:1157–1163. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heise L., Garcia-Moreno C. Violence by Intimate Partners. In: Krug E.G., Dahlberg L.L., Mercy J.A., Zwi A.B., Lozano R., editors. World Report on Violence and Health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. pp. 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreno C.G. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. Section 2: Results—Lifetime Prevalence Estimates; pp. 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zilkens R.R., Smith D.A., Kelly M.C., Mukhtar S.A., Semmens J.B., Phillips M.A. Sexual assault and general body injuries: A detailed cross-sectional Australian study of 1163 women. Forensic Sci. Int. 2017;279:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coker A.L., Smith P.H., McKeown R.E., King M.J. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: Physical, sexual, and psychological battering. Am. J. Public Health. 2000;90:553–559. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coker A.L., Davis K.E., Arias I., Desai S., Sanderson M., Brandt H.M., Smith P.H. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell J.C. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitman R.K., Rasmusson A.M., Koenen K.C., Shin L.M., Orr S.P., Gilbertson M.W., Milad M.R., Liberzon I. Biological studies of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;13:769–787. doi: 10.1038/nrn3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meewisse M.L., Reitsma J.B., De Vries G.J., Gersons B.P.R., Olff M. Cortisol and post-traumatic stress disorder in adults—Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007;191:387–392. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horn S.R., Feder A. Understanding Resilience and Preventing and Treating PTSD. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 2018;26:158–174. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sikkema K.J., Mulawa M.I., Robertson C., Watt M.H., Ciya N., Stein D.J., Cherenack E.M., Choi K.W., Kombora M., Joska J.A. Improving AIDS Care After Trauma (ImpACT): Pilot Outcomes of a Coping intervention Among HIV-Infected Women with Sexual Trauma in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:1039–1052. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-2013-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jewkes R.K., Dunkle K., Nduna M., Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376:41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunkle K.L., Jewkes R.K., Brown H.C., Gray G.E., McIntryre J.A., Harlow S.D. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell J.C., Baty M.L., Ghandour R.M., Stockman J.K., Francisco L., Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: A review. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2008;15:221–231. doi: 10.1080/17457300802423224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silverman J.G., Gupta J., Decker M.R., Kapur N., Raj A. Intimate partner violence and unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, induced abortion, and stillbirth among a national sample of Bangladeshi women. Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2007;114:1246–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall M., Chappell L.C., Parnell B.L., Seed P.T., Bewley S. Associations between Intimate Partner Violence and Termination of Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11:25. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coker A.L. Does physical intimate partner violence affect sexual health? A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2007;8:149–177. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruan W.J., Goldstein R.B., Chou S.P., Smith S.M., Saha T.D., Pickering R.P., Dawson D.A., Huang B., Stinson F.S., Grant B.F. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vitoria-Estruch S., Romero-Martinez A., Lila M., Moya-Albiol L. Could Alcohol Abuse Drive Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators’ Psychophysiological Response to Acute Stress? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:2729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonard K.E. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: When can we say that heavy drinking is a contributing cause of violence? Addiction. 2005;100:422–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foran H.M., O’Leary K.D. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devries K.M., Child J.C., Bacchus L.J., Mak J., Falder G., Graham K., Watts C., Heise L. Intimate partner violence victimization and alcohol consumption in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2014;109:379–391. doi: 10.1111/add.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverman J.G., Raj A., Mucci L.A., Hathaway J.E. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2001;286:572–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valentine A., Akobirshoev I., Mitra M. Intimate Partner Violence among Women with Disabilities in Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:947. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16060947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez I., Kershaw T.S., Keene D., Perez-Escamilla R., Lewis J.B., Tobin J.N., Ickovics J.R. Acculturation and Syndemic Risk: Longitudinal Evaluation of Risk Factors Among Pregnant Latina Adolescents in New York City. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018;52:42–52. doi: 10.1007/s12160-017-9924-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edirne T., Can M., Kolusari A., Yildizhan R., Adali E., Akdag B. Trends, characteristics, and outcomes of adolescent pregnancy in eastern Turkey. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010;110:105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith P.H., White J.W., Holland L.J. A longitudinal perspective on dating violence among adolescent and college-age women. Am. J. Public Health. 2003;93:1104–1109. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez-Marco A., Soares P., Davo-Blanes M.C., Vives-Cases C. Identifying Types of Dating Violence and Protective Factors among Adolescents in Spain: A Qualitative Analysis of Lights4Violence Materials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:2243. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glass N., Fredland N., Campbell J., Yonas M., Sharps P., Kub J. Adolescent dating violence: Prevalence., risk factors, health outcomes, and implications for clinical practice. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32:227–238. doi: 10.1177/0884217503252033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dosil M., Jaureguizar J., Bernaras E., Sbicigo J.B. Teen Dating Violence, Sexism, and Resilience: A Multivariate Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:2652. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waalen J., Goodwin M.M., Spitz A.M., Petersen R., Saltzman L.E. Screening for intimate partner violence by health care providers—Barriers and interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000;19:230–237. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pronyk P.M., Hargreaves J.R., Kim J.C., Morison L.A., Phetla G., Watts C., Busza J., Porter J.D.H. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1973–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McFarlane J., Soeken K., Wiist W. An evaluation of interventions to decrease intimate partner violence to pregnant women. Public Health Nurs. 2000;17:443–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2000.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. Lancet. 2002;359:1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta G.R., Parkhurst J.O., Ogden J.A., Aggleton P., Mahal A. HIV prevention 4—Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372:764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ellsberg M., Arango D.J., Morton M., Gennari F., Kiplesund S., Contreras M., Watts C. Prevention of violence against women and girls: What does the evidence say? Lancet. 2015;385:1555–1566. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson K., van Ee E. Mothers and Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Review of Treatment Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:1955. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alpert E.J. Violence in Intimate-Relationships and the Practicing Internist—New Disease or New Agenda. Ann. Intern. Med. 1995;123:774–781. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Short L.M., Johnson D., Osattin A. Recommended components of health care provider training programs on intimate partner violence. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998;14:283–288. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ugolini D., Neri M., Cesario A., Bonassi S., Milazzo D., Bennati L., Lapenna L.M., Pasqualetti P. Scientific production in cancer rehabilitation grows higher: A bibliometric analysis. Support. Care Cancer. 2012;20:1629–1638. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He L.G., Fang H., Wang X.L., Wang Y.Y., Ge H.W., Li C.J., Chen C., Wan Y.H., He H.D. The 100 most-cited articles in urological surgery: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2020;75:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He L.G., Fang H., Chen C., Wu Y.Q., Wang Y.Y., Ge H.W., Wang L.L., Wan Y.H., He H.D. Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Academic insights and perspectives through bibliometric analysis. Medical. 2020;99:14. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaplan W.A., Ritz L.S., Vitello M., Wirtz V.J. Policies to promote use of generic medicines in low and middle income countries: A review of published literature, 2000–2010. Health Policy. 2012;106:211–224. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen H.Q., Wang X.P., He L., Chen P., Wan Y.H., Yang L.Y., Jiang S.A. Chinese energy and fuels research priorities and trend: A bibliometric analysis. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2016;58:966–975. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Viedma-Del-Jesus M.I., Perakakis P., Munoz M.A., Lopez-Herrera A.G., Vila J. Sketching the first 45 years of the journal Psychophysiology (1964-2008): A co-word-based analysis. Psychophysiology. 2011;48:1029–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma B., Lawrence D.W. Top-cited articles in traumatic brain injury. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014;8:14. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rubin R.M., Chang C.F. A bibliometric analysis of health economics articles in the economics literature: 1991–2000. Health Econ. 2003;12:403–414. doi: 10.1002/hec.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Merigo J.M., Rocafort A., Aznar-Alarcon J.P. Bibliometric Overview of Business & Economics Research. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016;17:397–413. doi: 10.3846/16111699.2013.807868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu T.F., Hu H.L., Ding X.F., Yuan H.D., Jin C.B., Nai J.W., Liu Y.J., Wang Y., Wan Y.H., Tao X.Y. 12 years roadmap of the sulfur cathode for lithium sulfur batteries (2009–2020) Energy Storage Mater. 2020;30:346–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ensm.2020.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Du H.B., Li N., Brown M.A., Peng Y.N., Shuai Y. A bibliographic analysis of recent solar energy literatures: The expansion and evolution of a research field. Renew. Energy. 2014;66:696–706. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2014.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu X.J., Zhang L.A., Hong S. Global biodiversity research during 1900–2009: A bibliometric analysis. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011;20:807–826. doi: 10.1007/s10531-010-9981-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lennox R., Cooke S.J. State of the interface between conservation and physiology: A bibliometric analysis. Conserv. Physiol. 2014;2:9. doi: 10.1093/conphys/cou003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pritchard A. Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics. J. Doc. 1969;25:248. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu X., Rong J.F., Chen H., He C.L., Hu W.S., Wang Q. An informatics-based analysis of developments to date and prospects for the application of microalgae in the biological sequestration of industrial flue gas. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;100:2073–2082. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-7277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu Y.Q., Wan Y.H., Zhang F.Z. Characteristics and Trends of C-H Activation Research: A Review of Literature. Curr. Org. Synth. 2018;15:781–792. doi: 10.2174/1570179415666180426115417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bao G.J., Fang H., Chen L.F., Wan Y.H., Xu F., Yang Q.H., Zhang L.B. Soft Robotics: Academic Insights and Perspectives Through Bibliometric Analysis. Soft Robot. 2018;5:229–241. doi: 10.1089/soro.2017.0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller G.E., Chen E., Zhou E.S. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychol. Bull. 2007;133:25–45. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kessler R.C., Bromet E.J. The Epidemiology of Depression Across Cultures. In: Fielding J.E., editor. Annual Review of Public Health. Volume 34. Annual Reviews; Palo Alto, CA, USA: 2013. pp. 119–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Higgins J.A., Hoffman S., Dworkin S.L. Rethinking Gender, Heterosexual Men, and Women’s Vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100:435–445. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jewkes R., Morrell R. Gender and sexuality: Emerging perspectives from the heterosexual epidemic in South Africa and implications for HIV risk and prevention. J. Int. Aids Soc. 2010;13:6. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jewkes R.K., Levin J.B., Penn-Kekana L.A. Gender inequalities, intimate partner violence and HIV preventive practices: Findings of a South African cross-sectional study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003;56:125–134. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosser-Liminana A., Suria-Martinez R., Perez M.A.M. Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: Association Among Battered Mothers’ Parenting Competences and Children’s Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:1134. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Latzman N.E., Vivolo-Kantor A.M., Clinton-Sherrod A.M., Casanueva C., Carr C. Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: A systematic review of measurement strategies. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017;37:220–235. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2017.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.WHO . RESPECT Women: Preventing Violence against Women. World Health Organization; Geneva, Swizerland: 2019. [Google Scholar]