Abstract

Traditionally hazard quotients (HQs) have been computed for ecological risk assessment, often without quantifying the underlying uncertainties in the risk estimate. We demonstrate a Bayesian network approach to quantitatively assess uncertainties in HQs using a retrospective case study of dietary mercury (Hg) risks to Florida panthers (Puma concolor coryi). The Bayesian network was parameterized, using exposure data from a previous Monte Carlo-based assessment of Hg risks (Barron et al., 2004. ECOTOX 13:223), as a representative example of the uncertainty and complexity in HQ calculations. Mercury HQs and risks to Florida panthers determined from a Bayesian network analysis were nearly identical to those determined using the prior Monte Carlo probabilistic assessment and demonstrated the ability of the Bayesian network to replicate conventional HQ-based approaches. Sensitivity analysis of the Bayesian network showed greatest influence on risk estimates from daily ingested dose by panthers and mercury levels in prey, and less influence from toxicity reference values. Diagnostic inference was used in a high-risk scenario to demonstrate the capabilities of Bayesian networks for examining probable causes for observed effects. Application of Bayesian networks in the computation of HQs provides a transparent and quantitative analysis of uncertainty in risks.

Keywords: Bayesian networks, Terrestrial risk assessment, Mercury, Florida panther, Dynamic discretization, Monte Carlo analysis

1. Introduction

The ecological risk assessment process provides a logical and useful framework for examining potential risks from environmental stressors to ecological receptors, but the quantitative approaches for analyzing the data are much more likely to change than the framework itself as analytical methods advance (Newman, 1998). The ecological risk assessment process for wildlife species requires characterizing multiple exposure factors and extrapolating effects from surrogate species to assessment endpoints. Numerous quantified and unquantified uncertainties exist that propagate from effects and exposure analysis to the characterization of risks. Past literature has demonstrated and provided guidance on how Bayesian networks can provide useful tools for analyzing uncertainty and supporting causal inferences in ecological risk assessment problems (Carriger et al., 2016). Marcot et al. (2006) outlined steps in Bayesian network development including first establishing an influence diagram of the purported causal network, then developing a first level Bayesian network. Pollino and Henderson (2010) provided a useful introduction to Bayesian networks and describe an iterative process for building and using Bayesian networks from identifying model objectives to evaluating the model and examining scenarios. Pollino et al. (2007) noted that a Bayesian network for ecological risk assessment can be improved by combining both data and expert elicitation into parameterization. Application of Bayesian networks to risk assessment offers opportunities for identifying causal linkages, quantitatively predicting the greatest contributions to risk and, ultimately, prioritizing remedial actions (Marcot et al., 2006; Pollino et al., 2007).

We demonstrate a proof of concept application of Bayesian networks to hazard quotients (HQs) as conventionally calculated and applied in ecological risk assessments. We use the probabilistic assessment of historical dietary risks of mercury in Florida panthers (Puma concolor coryi) as a case study of the uncertainty and complexity in the derivation of HQs (Barron et al., 2004). Typically, an HQ is computed as the ratio of exposure concentration divided by an effect concentration (e.g., USEPA, 1998). For dietary risks, exposure as a total daily ingested dose is computed based on organism size, ingestion rate, contaminant level in food, and proportion of the diet that is contaminated. Adverse effect levels for wildlife are normally expressed as a toxicity reference value (TRV) that is extrapolated from laboratory toxicity tests using a representative test species and a subjective assessment of uncertainty and relevance of test endpoints (e.g., acute, chronic), exposure regime, and taxonomic or toxicological similarity (McDonald and Wilcockson, 2003).

We first developed a Bayesian network parameterized using exposure data from the original Monte Carlo-based assessment of Hg risks in Barron et al. (2004) as a case study. We then compared the Bayesian network-computed HQs to classical probabilistic risk estimates using retrospective low and high scenarios of mercury exposure in Florida panthers. Finally, we assessed sources of uncertainty in the computed dietary HQs, and the utility of a Bayesian network approach to assessments of ecological risk.

2. Case study and conceptual model

The case study was based on two retrospective risk scenarios presented in Barron et al. (2004) for low and high dietary Hg exposure in the Florida panther, an endangered subspecies of Puma concolor. The objective was to compare a Bayesian approach to hazard calculations to traditional Monte Carlo based risk methods. The panther metapopulation primarily occurs in the Everglades, Big Cypress ecosystem, and other habitats of South Florida many of which are areas of high historical Hg contamination in water, soils and aquatic-based food webs (Raimondo and Barron, 2008; Duvall and Barron, 2000; Osborne et al., 2011). Trophic transfer of Hg to panthers from preying on piscivorus wildlife has been considered a possible contributing factor to historical population declines and individual panther deaths across the south Florida ecosystem (Barron et al., 2004; Newman et al., 2004). The high-risk scenario focused on the aquatic-based pathway of Hg exposure to panthers: consumption of raccoons and other piscivorous wildlife that prey on fish, crustaceans and turtle eggs (Duvall and Barron, 2000; Barron et al., 2004).

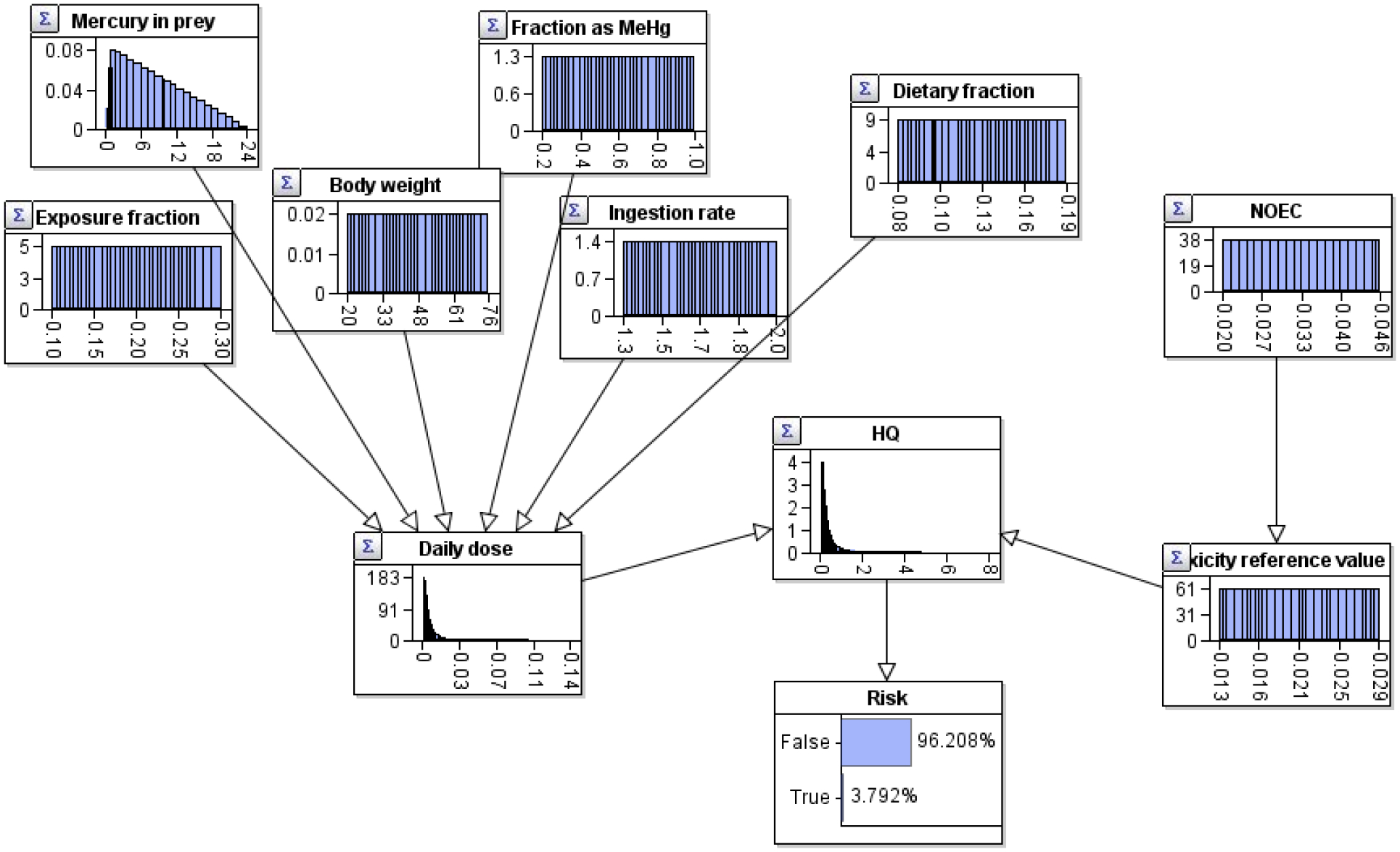

A conceptual model was developed to represent the functional causality in the flow of the equations (Fig. 1). The Bayesian network structure followed the equations used by Barron et al. (2004) to connect the variables. The Bayesian network estimates the exposure level and the toxicity level and combines the two estimates into a HQ which divides a high exposure concentration by a low effects concentration. If the exposure concentration is greater than the effect concentration, then that implies risk. Since this risk assessment is probabilistic, the distribution of exposure and effects, which incorporates high and low estimates in both, are compared to give a probability of risk rather than an indication of risk as is often done with deterministic HQ assessments.

Fig. 1.

Bayesian network qualitative structure for calculating risks to the Florida panther from Hg exposure. Exposure input variables are used to estimate a daily dose and Toxicity data is modified for a conservative toxicity reference value. Exposure and Toxicity (effects) are combined to calculate a distributed Hazard Quotient and the probability of the hazard quotient being greater than 1 is used to calculate Risk.

Mercury risks were determined using the HQ approach, with dietary exposure as the numerator and a toxicity reference value (TRV) as the denominator (Fig. 2). Mercury exposure in panthers was computed using a conventional dietary exposure model: average daily dose = [Hg] × ingestion rate × (DF/panther body weight) where DF was the fraction of piscivorous wildlife in the panther diet. Mercury concentrations [Hg] were computed from the proportion of methylmercury in prey and historical levels of contamination (Barron et al., 2004). Factors influencing the uncertainty of the HQ are shown as boxes and include errors in aggregation, extrapolation, measurement, and sampling (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Factors affecting the magnitude and uncertainty of a hazard quotient (HQ) for determining ecological risks of dietary exposures (adapted from NRC, 1994).

2.1. Probabilistic risk estimations using Monte Carlo analysis and Bayesian networks

Monte Carlo simulations can generate an output risk distribution given input distributions for exposure and effects variables in probabilistic risk assessments and equations relating the inputs to the outputs (Suter, 2007). Risk assessments for terrestrial organisms commonly use Monte Carlo analyses to estimate risks from multimedia exposures. Thousands of computerized runs for various combinations of the input variable values are done with an algorithm for selecting input variable combinations that are combined to derive a resulting distribution for the output variables. Bayesian networks, by contrast, are probabilistic graphical models that represent variables as nodes (circles) and connect them using arcs (arrows) (Pearl, 1988). Each variable connection has a quantitative function (commonly a conditional probability table) that designates how the child node is related to the parent. The conditional probabilities relating variables can be manually input into a conditional probability table, derived from a dataset, or derived (sampled) from an equation. The latter is analogous to the equations used in Monte Carlo analysis. Deterministic relationships are a special kind of conditional relationship that assumes 100 % occurrence for one or more combinations of parent states and a child state outcome. Nodes without incoming arcs have an unconditional probability distribution. Once the conditional and unconditional relationships are specified the joint probability distribution of the variables can be derived and marginal probabilities calculated for each variable. Soft or hard evidence can be input into one or more nodes and the probabilities are updated on variables throughout the model depending on any other evidence and the relationships among the variables.

2.2. Dynamic discretization

Bayesian networks often assume that variables are discrete for ease of computation when building and compiling models and performing inferences. Continuous variables are translated into discrete variables manually or using several types of automated methods. This discretization causes a loss of information and can bias results in some instances. Bayesian network approaches that accommodated continuous variable representations were historically restrictive by limiting the types of variables, distributions, and inferences that can be performed. This changed with the introduction and implementation of dynamic discretization described in Neil et al. (2007) and based on Kozlov and Koller (1997). Dynamic discretization automates the process of deriving intervals by selecting discretization thresholds based on an information theory measure (Kullback-Leibler) of divergence between the continuous and discretized distributions. The discretization process is iterative to converge on an acceptable level of accuracy in approximating the continuous distribution. The areas of the distribution that might be lost if discretization is too coarse are prioritized while the areas where finer discretization does not capture additional information about the distribution are avoided. In this way, the algorithm efficiently discretizes and converges on the estimates for a continuous distribution. The algorithm is responsive and usable when inferences are performed in the network by dynamically updating the discretizations based on the influence of any findings input into the models. Fenton and Neil (2018) contains additional examples and a technical appendix that explains dynamic discretization in-depth.

3. Model parameterization

The Bayesian network model was parameterized and quantified with equations and data from Barron et al. (2004) for scenarios of low and high Hg exposure (Table 1). All networks were built and run in Agenarisk software (version 10; revision 6532) (Agena, 2019). As with Barron et al. (2004), we assume there are no correlations among the input variables. Dynamic discretization was implemented using the default simulation convergence parameter value (0.001) which is used to set the accuracy of the simulation and is equivalent to the entropy error (Agena Ltd, 2019). Setting this value too low can increase simulation times so it is used as a tradeoff between efficiency and accuracy (Fenton and Neil, 2018). Default values were also used on other simulation parameters. The maximum number of iterations was 50, which is usually sufficient based on guidance for optimizing a discretization scheme (Agena Ltd., 2019). The evidence tolerance was set at 1.0% which is a heuristic used to establish an interval for hard evidence so that the probability value of the evidence is not zero (Fenton and Neil, 2018). Tails were not discretized (an option for adding additional intervals in the tail regions of the distribution) for this case study in order to examine the accuracy of the default settings. Tornado graphs were used for sensitivity analysis for the probability of risk being true (p(HQ) > 1). The range of probabilities for risk being true were calculated from each sensitivity node by varying each node individually from a low to high centile (0 and 100, respectively) and recording the corresponding probability range for risk being true. The HQ node was not included as a sensitivity node given its redundancy with the Risk node. All analyses were conducted using the sensitivity analysis tool in AgenaRisk.

Table 1.

Description of nodes in the Bayesian network models for assessing risks from mercury exposure to the Florida panther (Puma concolor coryi). Distributions and functions were from Barron et al. (2004).

| Node name | Abbreviation | Units | Parent nodes | Calculation type | Function (=) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure fractiona | EF | unitless | None | Distribution | Low exposure: Uniform (0.1, 0.3)b High exposure: 1 |

| Mercury in prey | Hg | mg/kg | None | Distribution | Triangle (0.2, 24, 1)c |

| Body weight | BW | kg | None | Distribution | Uniform (19.5, 75.6) |

| Fraction as MeHg | FHg | unitless | None | Distribution | Uniform (0.2, 1) |

| Ingestion rate | IR | kg/d | None | Distribution | Uniform (1.3, 2) |

| Dietary fractiond | DF | unitless | None | Distribution | Uniform (0.076, 0.19) |

| Daily dosee | ADD | mg/kg/day | Hg, FHg, IR, DF, BW, EF | Equation | (Hg*FHg*IR*DF/BW)*EF |

| NOECf | NOEC | mg/kg/day | None | Distribution | Uniform (0.02, 0.046) |

| Toxicity reference valuee | TRV | mg/kg/day | NOEC | Equation | NOEC*(3/19.5)^0.25 |

| HQ | HQ | unitless | ADD, TRV | Equation | ADD/TRV |

| Risk | R | % exceedenceg | HQ | Expression | if(HQ>1,”True”,”False”) |

Fraction of historical Hg exposure.

Uniform distribution (range).

Triangular distribution (min, max, mode).

Fraction of panther diet consisting of piscivorous wildlife.

Equation from Sample et al. (1996).

No effect concentration range for sublethal neurological impairment.

Risk is calculated as percentage of the HQ distribution that exceeds 1 (then risk is true, otherwise it is false) for sublethal neurological impairment.

4. Comparison of risk estimates

Risk as the probability of the exposure distribution exceeding the effects distribution (the HQ) in the high exposure scenario was calculated with a Bayesian network (Fig. 3). The input nodes are the root nodes and contain the distributions specified in Barron et al. (2004) and shown in Table 1. The intermediate nodes were the Daily dose, Toxicity reference value, and HQ and were the calculated results for exposure, effects, and risk characterization, respectively. The Risk node indicates there is a 46 % probability the HQ is greater than 1. This is equivalent to the probability estimated in Barron et al. (2004) using Monte Carlo methods (Table 2). The risk for the low exposure scenario was calculated with a Bayesian network approach using the input distributions of Barron et al. (2004) (Fig. 4). For the risk calculation in the low exposure scenario, the last significant figure (decimal point in a percent probability) was off by one digit (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Bayesian network calculating risks to the Florida panthers from Hg exposure for the high exposure scenario.

Table 2.

Comparison of Bayesian network and Monte Carlo calculations of percent of hazard quotients exceeding a value of 1 for sublethal neurological impairment for two retrospective scenarios.

| Mercury Exposure Scenario | Probability of Risk | |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Network | Monte Carlo (Barron et al. 2004) | |

| Low | 3.8% | 3.7% |

Fig. 4.

Bayesian network calculating risks to the Florida panthers from Hg exposure for the low exposure scenario.

5. Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was run on the Bayesian networks to examine which risk factors have the greatest potential impact on the HQ being greater than one (p(Risk=True)). Tornado plots were used for sensitivity analysis to show the range of potential impacts from varying exposure and effects individually on the subsequent risk estimates. In general, the variables had the same rank order between the exposure scenarios due to the similar input distributions. The risk probability was most sensitive to the distribution of Daily dose for the high exposure scenario (Fig. 5) and low exposure scenario (Fig. 6). For the input variables, Mercury in prey had the greatest potential impact on risk probabilities followed by Fraction as MeHg (Fig. 5) or Body weight (Fig. 6). The risk being true was more sensitive to Mercury in prey in the high exposure than the low exposure scenario, with a 0.0 to 0.94 probability of true risk with high exposure and 0.0 to 0.24 probability with low exposure. For the low exposure scenario, the highest probability of risk that was obtained from the sensitivity analysis for the other variables was 0.164 for Body weight. The range of probabilities still exhibited a potential of greater than 0.50 probability for risk for all remaining variables in the high exposure scenario. The Toxicity reference value and the NOEC had a lesser range of potential impact from the sensitivity analysis than the majority of the exposure-related variables for the high and low exposure scenarios. Still, in the high exposure scenarios, the range of values for these variables corresponded with a probability of risk being true lower (~0.3) and greater (~0.6) than 0.5 (Fig. 5). For the low exposure scenario, the probability of risk being true did not exceed 0.100 for the range of values in these effect-related variables (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Sensitivity analysis results for the probability of the hazard quotient being greater than 1 (p(Risk=True)) for the high exposure scenario.

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity analysis results for the probability of the hazard quotient being greater than 1 for the low exposure scenario.

6. Using a Bayesian network to diagnose a high-risk scenario

One of the advantages of a Bayesian network is the ability to perform predictive (forward), diagnostic (backward), and mixed (forward and backward) inference. The prior two scenarios were based on predictive inference to update the marginal probabilities of the nodes based on the probability of the parents and the conditional relationships. A diagnostic scenario was developed to illustrate the capability for examining probabilities of risk factors that would result in a specific risk level (Fig. 7). In this scenario, a risk of true was input in the Risk leaf node (100 % probability of being true) for the low exposure scenario and the probabilities for all the nodes were examined. Inputting a finding on a node in a Bayesian network updates the prior probabilities in the model to posterior probabilities based on the structural relationships and the conditional and unconditional probabilities. The initial probability distributions specified from Barron et al. (2004) were used to construct prior probabilities. The updated distributions became posterior probabilities calculated using Bayes theorem from the finding of a true state placed on the Risk node and the distributional changes that propagate to the target nodes of interest. The probability distributions became more skewed when a true risk to the panther is for certain. For the HQ node, the probability distribution shifted from zero to one for the start of the density function. Higher values became more probable for many of the exposure distributions and lower values became more probable for the effects distributions. The Body weight distribution has a higher density among lower values within the range of body weights indicating that smaller panthers are more likely to experience this risk scenario. The probability for higher fractions of methylmercury in prey (Fraction as MeHg) increases along with Ingestion rate. Different scenarios can be input into a Bayesian network and probabilities of key predecessor variables that could lead to this compared, which is a powerful tool not found in standard Monte Carlo analyses.

Fig. 7.

Diagnosing a high-risk scenario (p(Risk = True) = 100 %) using a prior model from Fig. 4. Posterior probabilities are displayed for all other variables when this finding is input into the model.

7. Discussion

Mercury risks to panthers determined with a Bayesian network were nearly identical to estimates determined in a Monte Carlo-based assessment, showing the ability of the Bayesian network approach to replicate estimates from conventional risk analyses. Utilization of dynamic discretization within the network allowed greater resolution and less uncertainty in parameter estimation. Dynamic discretization is a parameter learning approach for continuous variables in Bayesian networks that has previously found to be accurate for approximating distributions and Bayesian analysis (Neil et al., 2007). Although it was first developed over ten years ago, it has been infrequently applied to ecological risk assessments. From the results of this study, Bayesian networks with dynamic discretization might be a viable platform for examining the implications of ecological risk assessment data. The work in this article utilized a previous risk assessment for Hg and the Florida panther and compared the output from a Bayesian network to the output from a standard Monte Carlo analysis used in that article (Barron et al., 2004). The estimates in this case, were close enough to warrant consideration of Bayesian networks in future applications for Hg and the Florida panther and other ecological risk assessment problems.

There are numerous uncertainties in ecological risk assessments (e.g., Fig. 2). Many uncertainties will not be captured in the probabilities used in the assessment as the complexity of the environment can never be completely captured in a mathematical model (Reckhow, 1999). The process for developing quantitative risk assessment models often requires a tiered approach to refine uncertainties, evaluate their inclusion in the model, and consider the value of information in collecting new data. In this approach, sensitivity analysis is used to focus higher tiers. Lower tiers require less information and are more conservative (ECOFRAM, 1999). Higher tiers incorporate more information and greater realism. As the analysis is refined and the tiers progress, assurances are needed that high-risk scenarios are not missed due to lack of data or inaccurate modeling scope. If low-risk is determined at one tier with sufficient confidence, then a higher tier analysis is not required. If high enough risk is identified, then remedial actions may be required before higher tiers of analysis are completed (ECOFRAM, 1999). The capabilities of Bayesian networks for piecing together the data and information sources and updating model structure and probabilities makes them useful candidates for tiered risk assessment processes (Nyberg et al., 2006; Lehikoinen et al., 2015).

Building a Bayesian network requires consideration of the relationships among the variables in the problem. The notion of conditional independence is used to ensure that the Bayesian network meets structural assumptions for proper inferences. Two variables are conditionally independent given a third variable if changes to one of the first two variables will not influence the probability distribution of the other given that the third variable is known (Pearl, 2009). Conditional independence is a requirement for probabilistic analyses outside of Bayesian networks but the network structure can be used to help clarify the conditional independence relationships assumed in the model. For the current model, we assumed that the calculations used in Barron et al. (2004) captured the conditional independence among the relationships between the variables.

A Bayesian network, by definition, is not necessarily causal as conditional independence can be captured in acausal models. For causal model building, Carriger et al. (2018) discuss how the qualitative portion of Bayesian networks can be structured and used for knowledge representation and causal modeling in environmental management. In a classic and relevant paper, Neil et al. (2000) presents idioms or Bayesian network model types that can be pieced together for building problem-oriented Bayesian networks. Cain (2001) gives specific guidance for building Bayesian networks for environmental management. A literature review for engineering model development identified four general methods for eliciting the structure: automated learning from data, manual construction with expert knowledge, adapting the structure of other graphical probabilistic models (e.g., fault/event trees), and adapting the variables and relationships from mechanistic and empirical models (Zwirglmaier and Straub, 2017). Similar to the latter model-building approach, the current model blends the mechanistic and statistical relationships in the equations used by Barron et al. (2004) to characterize risks to Florida panthers. As an extension, this and similar wildlife risk assessment models could be transferred into a causal Bayesian network by translating the HQ and risk calculation into a potential adverse event that reflects a neurological impairment to an individual panther from cumulative ingestion of mercury.

Throughout the phases of a tiered ecological risk assessment approach, modern tools of causal modeling can be applied to help make causal assumptions explicit as testable hypotheses but the application and knowledge of these tools among risk assessors is still limited (Carriger and Barron, 2016). Bayesian networks are a better fit with causal modeling over standard Monte Carlo analysis due to their transparent graphical representation of the cause and effect relationships. The diagrammatic approach for Bayesian networks eases the process of mapping the causes and effects into a quantitative model. Some problems require greater structural depth to represent the causal uncertainties and evidence needed for estimating risks. In these cases, the Bayesian network can expand the standard risk equations to include more variables and key uncertainties influencing risks. Thus, additional extensions can be used for the root nodes (e.g., contamination source events) or anywhere in the model as one of the benefits of a Bayesian network structure (Lehikoinen et al., 2015; Zwirglmaier and Straub, 2017). Although some of the variables and relationships in the current model do not or can only indirectly represent potential real-world events, the flow of the network and equations reflect a functional causality from exposure and toxicity to risk characterization. Whether it is directly empirically quantified or not, building a causal diagram of potential outcomes in the risk problem through conceptual modelling focuses the data gathering efforts and fosters greater understanding of the ecological risk problem. Bayesian networks allow the relationships in the conceptual models to be rigorously adapted, whole or in part, to the quantification of exposure and risks (Landis et al., 2017).

The capabilities for performing diagnostic, mixed, and predictive inference make Bayesian networks especially useful for examining the causal factors that could lead to higher or lower risk outcomes. The structure can be easily modified within a Bayesian network to include additional risk factors and causal levels for establishing probability distributions and including variables that are important to consider for assessment and management. As Bayesian network methods continue to expand and improve, their adoption in ecological risk assessment will follow and will be useful for testing and comparing with other tools for identifying more costs and benefits of their usage.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). We thank Mark Cunningham and Glenn Suter for reviews of a draft of the manuscript. Any mention of trade names, products, or services does not imply an endorsement by the U.S. Government or the EPA.

References

- Agena, 2019. AgenaRisk software, Revision 6019. Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Agena Ltd, 2019. AgenaRisk 10: Desktop User Manual. Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Barron MG, Duvall SE, Barron KJ, 2004. Retrospective and current risks of mercury to panthers in the Florida everglades. Ecotoxicology 13, 223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain J, 2001. Planning Improvements in Natural Resources Management: Guidelines for Using Bayesian Networks to Support the Planning and Management of Development Programmes in the Water Sector and Beyond. Centre for Ecology and Hydrology; Wallingford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Carriger JF, Barron MG, 2016. A practical probabilistic graphical modeling tool for ecological risk-based evidence. Soil Sed. Contam 25, 476–487. [Google Scholar]

- Carriger JF, Barron MG, Newman MC, 2016. Bayesian networks improve causal environmental assessments for evidence-based policy. Environ. Sci. Technol 50, 13195–13205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall SE, Barron MG, 2000. A screening-level probabilistic ecological risk assessment of mercury in Florida everglades food webs. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf 47, 298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECOFRAM, 1999. Ecological Committee on FIFRA Risk Assessment Methods. U.S. EPA. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton N, Neil M, 2018. Risk Assessment and Decision Analysis with Bayesian Networks. In: Boca Raton, FL, Second edition CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov AV, Koller D, 1997. Nonuniform dynamic discretization in hybrid networks In: Proceedings of the Thirteenth Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc; pp. 314–325. [Google Scholar]

- Landis WG, Ayre KK, Johns AF, Summers HM, Stinson J, Harris MJ, Herring CE, Markiewicz AJ, 2017. The multiple stressor ecological risk assessment for the mercury-contaminated South River and upper Shenandoah River using the Bayesian network-relative risk model. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manage 13 (1), 85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehikoinen A, Hänninen M, Storgård J, Louma E, Mäntyniemi S, Kuikka S, 2015. A Bayesian networks for assessing the collision induced risk of an oil accident in the Gulf of Finland. Environ. Sci. Technol 49, 5301–5309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcot BG, Steventon JD, Sutherland GD, McCann RK, 2006. Guidelines for developing and updating Bayesian belief networks applied to ecological modeling and conservation. Can. J. Res 36, 3063–3074. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald BG, Wilcockson JB, 2003. Improving the use of toxicity reference values in wildlife food chain modeling and ecological risk assessment. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess 9, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar]

- Neil M, Fenton N, Nielson L, 2000. Building large-scale Bayesian networks. Knowl. Eng. Rev 15 (3), 257–284. [Google Scholar]

- Neil M, Tailor M, Marquez D, 2007. Inference in hybrid Bayesian networks using dynamic discretization. Stat. Comput 17, 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Newman J, Zillioux E, Rich E, Liang L, Newman C, 2004. Historical and other patterns of monomethyl and inorganic mercury in the Florida Panther (Puma concolor coryi). Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol 48, 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MC, 1998. Fundamentals of Ecotoxicology. Ann Arbor Press, Chelsea, MI. [Google Scholar]

- NRC, 1994. Science and Judgment in Risk Assessment. National Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg JB, Marcot BG, Sulyma R, 2006. Using Bayesian belief networks in adaptive management. Can. J. For. Res 36, 3104–3116. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne TZ, Newman S, Scheidt DJ, Kalla PI, Bruland GL, Cohen MJ, Scinto LJ, Ellis LR, 2011. Landscape patterns of significant soil nutrients and contaminants in the Greater Everglades ecosystem: past, present, and future. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol 41 (Sup. 1), 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl J, 1988. Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems: Networks of Plausible Inference. Morgan Kaufmann, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl J, 2009. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Pollino CA, Henderson C, 2010. Bayesian Networks: a Guide for their Application in Natural Resource Management and Policy Landscape Logic, Technical Report No. 14. Australian Government, Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Pollino CA, Woodberry O, Nicholson A, Korb K, Hart BT, 2007. Parameterisation and evaluation of a Bayesian network for use in an ecological risk assessment. Environ. Model. Softw 22, 1140–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Reckhow KR, 1999. Water quality prediction and probability networks. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci 56, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Raimondo S, Barron MG, 2008. Population level modeling of mercury stress on the Florida panther metapopulation. Chapter 3 In: Akcakaya R (Ed.), Demographic Toxicity: Case Studies in Ecological Risk Assessment . Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sample BE, Opresko DM, Suter GW, 1996. Toxicological Benchmarks for Wildlife: 1996 revision. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN: ES/ER/TM −86/R3. [Google Scholar]

- Suter GW II, 2007. Ecological Risk Assessment, Second edition CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA, 1998. Guidelines for Ecological Risk Assessment. Risk Assessment Forum, Washington, DC: EPA/630/R-95/002F. April 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zwirglmaier K, Straub D, 2017. Approaches to Bayesian network structure elicitation In: Walls R, Bedford (Eds.), Risk, Reliability and Safety: Innovating Theory and Practice. Taylor & Francis, London UK [Google Scholar]