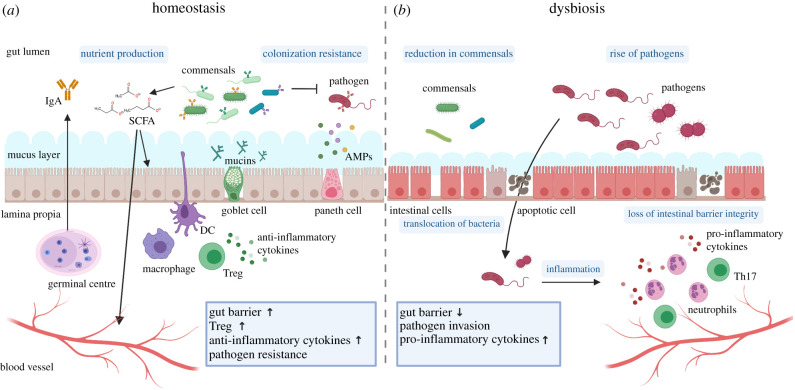

Figure 2.

Host–microbiota interactions under homeostatic and dysbiotic conditions. (a) Under homeostatic conditions, the intestine shows a well-balanced interplay between host and microbiota. The host allows specific microbes to reside in the lumen, which in turn provide nutrients, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), and help the defence against pathogens contributing to colonization resistance. To ensure proper homeostasis, the host actively selects for specific commensal bacteria—resulting in a diverse commensal community—while keeping the bacteria at a safe distance through the intestinal gut barrier. The gut barrier is composed of a thin layer of epithelial cells, a thick mucus barrier and defence molecules, such as anti-microbial peptides (AMPs). Mucin production by goblet cells and barrier function is enhanced by the bacterial-derived SCFA. Plasma cells in the lamina propria or the germinal centres (GC) produce secretory IgA, which coat both commensal and pathogenic bacteria. Intestinal macrophages produce large amounts of anti-inflammatory cytokines that block pro-inflammatory signals and promote regulatory T cells (Treg), which help maintain immune homeostasis in the intestine. (b) Under dysbiosis and ageing, the intestinal microbiota composition undergoes a reduction of commensal and a rise of pathogenic bacteria. Loss of intestinal barrier integrity enables translocation of bacteria into the host tissue, through the basement membrane into the lamina propria. Pathogen invasion results in a recruitment of inflammation-associated immune cells like neutrophils and Th17 cells, leading to a burst of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This figure was generated with Biorender.