Abstract

Background

Chest computed tomography (CT) is crucial for the detection of lung cancer, and many automated CT evaluation methods have been proposed. Due to the divergent software dependencies of the reported approaches, the developed methods are rarely compared or reproduced.

Objective

The goal of the research was to generate reproducible machine learning modules for lung cancer detection and compare the approaches and performances of the award-winning algorithms developed in the Kaggle Data Science Bowl.

Methods

We obtained the source codes of all award-winning solutions of the Kaggle Data Science Bowl Challenge, where participants developed automated CT evaluation methods to detect lung cancer (training set n=1397, public test set n=198, final test set n=506). The performance of the algorithms was evaluated by the log-loss function, and the Spearman correlation coefficient of the performance in the public and final test sets was computed.

Results

Most solutions implemented distinct image preprocessing, segmentation, and classification modules. Variants of U-Net, VGGNet, and residual net were commonly used in nodule segmentation, and transfer learning was used in most of the classification algorithms. Substantial performance variations in the public and final test sets were observed (Spearman correlation coefficient = .39 among the top 10 teams). To ensure the reproducibility of results, we generated a Docker container for each of the top solutions.

Conclusions

We compared the award-winning algorithms for lung cancer detection and generated reproducible Docker images for the top solutions. Although convolutional neural networks achieved decent accuracy, there is plenty of room for improvement regarding model generalizability.

Keywords: computed tomography, spiral; lung cancer; machine learning; early detection of cancer; reproducibility of results

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide, causing 1.76 million deaths per year [1,2]. Chest computed tomography (CT) scans play an essential role in the screening for [3] and diagnosis of lung cancer [4]. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that low-dose CT screening reduced mortality from lung cancer among high-risk patients [3], and recent studies showed the benefit of CT screening in community settings [5]. The wide adoption of lung cancer screening is expected to benefit millions of people [6]. However, millions of CT scan images obtained from patients constitute a heavy workload for radiologists [7]. In addition, interrater disagreement has been documented [8]. Previous studies suggested that computer-aided diagnostic systems could improve the detection of pulmonary nodules in CT examination [9-12]. To stimulate the development of machine learning models for automated CT diagnosis, the Kaggle Data Science Bowl provided labeled chest CT images from 1397 patients and awarded $1 million in prizes to the best algorithms for automated lung cancer diagnosis, which is the largest machine learning challenge on medical imaging to date. In response, 1972 teams worldwide have participated and 394 teams have completed all phases of the competition [13], making it the largest health care–related Kaggle contest [14]. This provides a unique opportunity to study the robustness of medical machine learning models and compare the performance of various strategies for processing and classifying chest CT images at scale.

Due to the improved performance of machine learning algorithms for radiology diagnosis, some developers have sought commercialization of their models. However, given the divergent software platforms, packages, and patches employed by different teams, their results were not easily reproducible. The difficulty in reusing the state-of-the-art models and reproducing the diagnostic performance markedly hindered further validation and applications.

To address this gap, we reimplemented, examined, and systematically compared the algorithms and software codes developed by the best-performing teams of the Kaggle Data Science Bowl. Specifically, we investigated all modules developed by the 10 award-winning teams, including their image preprocessing, segmentation, and classification algorithms. To ensure the reproducibility of results and the reusability of the developed modules, we generated a Docker image for each solution using the Docker Community Edition, a popular open-source software development platform that allows users to create self-contained systems with the desired version of software packages, patches, and environmental settings. According to Docker, there are over 6 million Dockerized applications, with 130 billion total downloads [15]. The Docker images are easily transferrable from one server to another, which ensures the reproducibility of scientific computing [16]. Our Dockerized modules will facilitate further development of computer-aided diagnostic algorithms for chest CT images and contribute to precision oncology.

Methods

Data and Classification Models

We obtained the low-dose chest CT datasets in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format from the Kaggle Data Science Bowl website [13]. The dataset was acquired from patients with high risks for developing lung cancers. In this Kaggle challenge, a training set (n=1397) with ground truth labels (362 with lung cancer; 1035 without) and a public test set (n=198) without labels were provided to the participants. The ground truth label is 1 if the patient developed lung cancer within 1 year of the date the CT scan was performed and 0 otherwise. The diagnosis was confirmed by pathology evaluation as a part of the National Lung Screening Trial [3,17]. Once participants submitted the prediction results for the public test set, the Kaggle competition platform reported their models’ performance on the public leaderboard instantaneously. The final test set (n=506, ground truth labels were not disclosed to participants) was only available to participants after the model submission deadline, thus serving as an independent validation set that decided the final winners. The chest CT images in the training set, public test set, and final test set all came from multiple hospitals and had different qualities. In particular, the final test set contained more recent and higher quality data with thinner slice thickness than those in the two other sets [18].

To systematically compare the solutions developed by the award-winning teams, we acquired the source codes of the winning solutions and their documentation from the Kaggle news release after the conclusion of the competition. Per the rules of this Kaggle challenge, the source codes of these award-winning solutions were required to be released under open-source licenses approved by the Open Source Initiative [19] in order to facilitate free distribution and derivation of the solution codes [20]. The default license is the MIT license [20]. Under the open-source licenses approved by Open Source Initiative, the software can be freely used, modified, and shared [19].

Comparison of the Approaches and Their Performance

We compared the workflows of the top 10 solutions by examining and rerunning their source codes. For each solution, we inspected all steps taken from inputting the CT images to outputting the prediction. We documented the versions of the software package and platform dependencies of each solution.

The Kaggle Data Science Bowl used the log-loss function to evaluate the performance of the models [13]. The log-loss function  where n is the number of patients in the test set, yi is 1 if patient i has lung cancer, 0 otherwise, and ŷi is the predicted probability that patient i has lung cancer [13]. If the predicted outcome is set as 0.5 for all patients, the log-loss value would be ln (2) ≈ 0.69.

where n is the number of patients in the test set, yi is 1 if patient i has lung cancer, 0 otherwise, and ŷi is the predicted probability that patient i has lung cancer [13]. If the predicted outcome is set as 0.5 for all patients, the log-loss value would be ln (2) ≈ 0.69.

To investigate whether models with high performance in the public test set generalize to the images in the final test set, we computed the Spearman correlation coefficient of the log-loss in the two test sets. All analyses were conducted using R version 3.6 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Docker Image Generation for the Top Ten Solutions

We reproduced the results by recompiling the source codes and dependencies of each of the top ten solutions. Since the solutions used various platforms and different versions of custom software packages, many of which were not compatible with the most updated packages or mainstream release, we generated Docker images [16] to manage the software dependencies and patches required by each solution to enhance the reusability and reproducibility of the developed algorithms.

Results

Performance Comparison

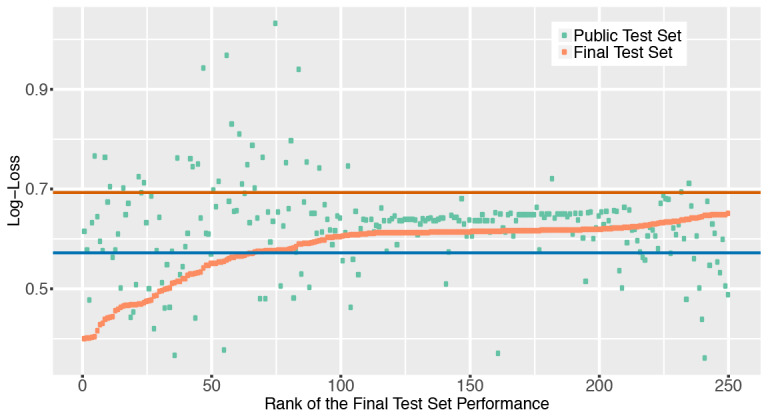

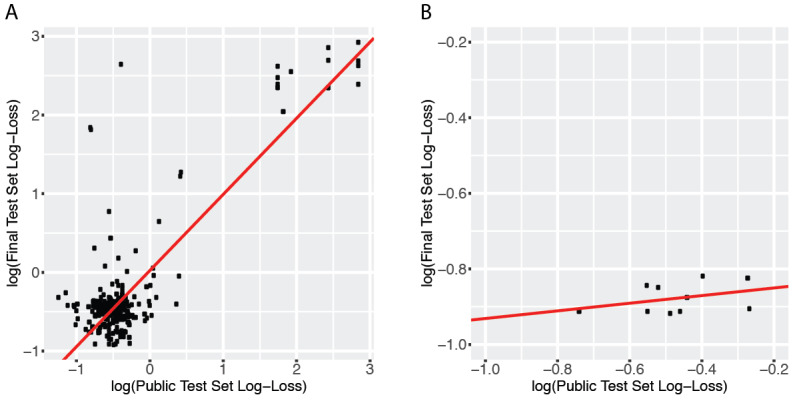

Figure 1 summarizes the public and private test set scores of the top 250 teams that participated in the Kaggle Data Science Bowl. Results showed that the top 20 teams achieved a log-loss less than 0.5 in the final test set, and more than 80 submissions reached a log-loss less than 0.6 in the same set. However, these models had varying performances in the public test set. Surprisingly, 11 out of the top 50 teams had a public test set log-loss greater than 0.69, which was worse than blindly submitting “0.5” as the cancer probability for every patient. The correlation between the public test set scores and the final test set scores was weak among all teams that completed the contest (Spearman correlation coefficient = .23; Figure 2A). In the top 10 teams, the correlation is moderate (Spearman correlation coefficient = .39; Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

The log-loss score distribution of the top 250 teams in the Kaggle Data Science Bowl Competition. The log-loss scores of the public test set and the final test set of each team were plotted. The red horizontal line indicates the log-loss of outputting the cancer probability as 0.5 for each patient. The blue horizontal line shows the log-loss of outputting cancer probability of each patient as the prevalence of cancer (0.26) in the training set.

Figure 2.

A weak to moderate correlation between the log-loss scores of the public test set and the scores of the final test set. The red regression line shows the relation between the log-loss scores of the public test set and those of the final test set using a linear regression model. (A) The log-transformed scores of all participants who finished both stages of the Kaggle Data Science Bowl Competition were plotted. The Spearman correlation coefficient of the performance in the two test sets is .23. (B) The log-transformed scores of the top 10 teams defined by the final test set performance. The Spearman correlation coefficient among the top 10 teams is .39.

Data Workflow Comparison

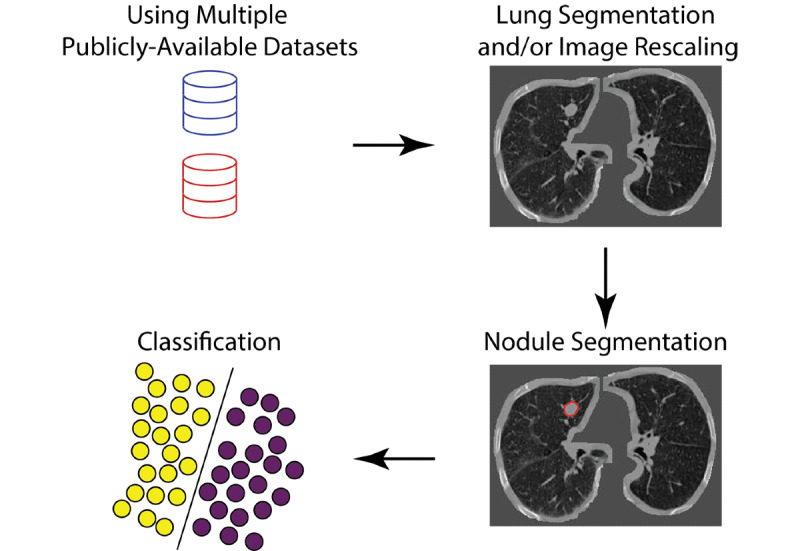

Figure 3 summarizes the most frequently used strategy by the winning teams. Most solutions used additional publicly available datasets, generated lung segmentation, rescaled the voxels, and performed nodule segmentations before fitting the classification models. Table 1 compares the additional datasets, data preprocessing, segmentation, classification, implementation, and final test set scores of the top 10 solutions.

Figure 3.

A model of the informatics workflow used by most teams. In addition to the Kaggle training set, most teams obtained additional publicly available datasets with annotations. Lung segmentation, image rescaling, and nodule segmentation modules were commonly used before classification.

Table 1.

Comparisons of the top-performing solutions of the Kaggle Data Science Bowl.

| Rank | Team name | Additional datasets used | Data preprocessing | Nodule segmentation | Classification algorithms | Implementation | Final test set score |

| 1 | Grt123 | LUNA16a | Lung segmentation, intensity normalization | Variant of U-Net | Neural network with a max-pooling layer and two fully connected layers | Pytorch | 0.39975 |

| 2 | Julian de Wit and Daniel Hammack | LUNA16, LIDCb | Rescale to 1×1×1 | C3Dc, ResNet-like CNNd | C3D, ResNet-like CNN | Keras, Tensorflow, Theano | 0.40117 |

| 3 | Aidence | LUNA16 | Rescale to 2.5×0.512×0.512 (for nodule detection) and 1.25×0.5×0.5 (for classification) | ResNete | 3D DenseNetf multitask model (different loss functions depending on the input source) | Tensorflow | 0.40127 |

| 4 | qfpxfd | LUNA16, SPIE-AAPMg | Lung segmentation | Faster R-CNNh, with 3D CNN for false positive reduction | 3D CNN inspired by VGGNet | Keras, Tensorflow, Caffe | 0.40183 |

| 5 | Pierre Fillard (Therapixel) | LUNA16 | Rescale to 0.625×0.625×0.625, lung segmentation | 3D CNN inspired by VGGNet | 3D CNN inspired by VGGNet | Tensorflow | 0.40409 |

| 6 | MDai | None | Rescale to 1×1×1, normalize HUi | 2D and 3D ResNet | 3D ResNet + a Xgboost classifier incorporating CNN output, patient sex, # nodules, and other nodule features | Keras, Tensorflow, Xgboost | 0.41629 |

| 7 | DL Munich | LUNA16 | Rescale to 1×1×1, lung segmentation | U-Net | 2D and 3D residual neural network | Tensorflow | 0.42751 |

| 8 | Alex, Andre, Gilberto, and Shize | LUNA16 | Rescale to 2×2×2 | Variant of U-Net | CNN, tree-based classifiers (with better performance) | Keras, Theano, xgboost, extraTree | 0.43019 |

| 9 | Deep Breath | LUNA16, SPIE-AAPMj | Lung mask | Variant of SegNet | Inception-ResNet v2 | Theano and Lasagne | 0.43872 |

| 10 | Owkin Team | LUNA16 | Lung segmentation | U-Net, 3D VGGNet | Gradient boosting | Keras, Tensorflow, xgboost | 0.44068 |

aLUNA16: Lung Nodule Analysis 2016.

bLIDC: Lung Image Database Consortium.

cC3D: convolutional 3D.

dResNet-like CNN: residual net–like convolutional neural network.

eResNet: residual net.

fDenseNet: dense convolutional network.

gSPIE-AAPM: International Society for Optics and Photonics–American Association of Physicists in Medicine Lung CT Challenge.

hR-CNN: region-based convolutional neural networks.

iHU: Hounsfield unit.

jDataset has been evaluated but not used in building the final model.

In addition to the training dataset provided by the Kaggle challenge, most teams used CT images and nodule annotations from other publicly available resources. Table 2 summarizes the sample size, availability of nodule locations, nodule segmentation, diagnoses, other characteristics of the Kaggle dataset, and additional datasets employed by the participants. Most of the top solutions used images and nodule segmentations from the Lung Nodule Analysis 2016 (LUNA16) challenge to develop their segmentation algorithms. LUNA16 is a closely related competition organized in 2016 with an aim to detect lung nodules in chest CT images [21,22]. Two teams also reported using the lung CT images, diagnostic annotations, and nodule location data from the International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE)–American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) Lung CT Challenge [23], but one of them did not incorporate this relatively small dataset (n=70) when building the final models. Only one of the top 10 teams did not use any additional datasets outside of the competition.

Table 2.

A summary of the chest computed tomography datasets employed by the participants.

| Datasets | Number of CTa scan series | Data originated from multiple sites | Availability of nodule locations | Availability of nodule segmentations | Availability of patients’ diagnoses (benign versus malignant) |

| Kaggle Data Science Bowl (this competition) | Training: 1397; public test set: 198; final test set: 506 | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Lung nodule analysis | 888 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| SPIE-AAPMb Lung CT Challenge | 70 | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Lung Image Database Consortium | 1398 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

aCT: computed tomography.

bSPIE-AAPM: International Society for Optics and Photonics–American Association of Physicists in Medicine.

Frequently used image preprocessing steps include lung segmentation and voxel scaling. Voxel scaling ensures that the voxels of images from various CT scan protocols correspond to similar sizes of physical space. Variants of U-Net [24], VGGNet [25], and residual net (ResNet) [26] were commonly used as the nodule segmentation algorithms, and the nodule segmentation models trained on the LUNA16 dataset were often applied to the Data Science Bowl dataset.

After lung nodule segmentation, classification algorithms were employed to generate final cancer versus noncancer predictions. Most of the solutions leveraged existing ImageNet-based architecture and transfer learning [12,27]. All teams employed 2D or 3D convolutional neural networks (CNN). A few teams employed CNNs as feature extractors and used tree-based classifiers for this classification task.

Comparison of the Implementation Platforms and Software Dependencies

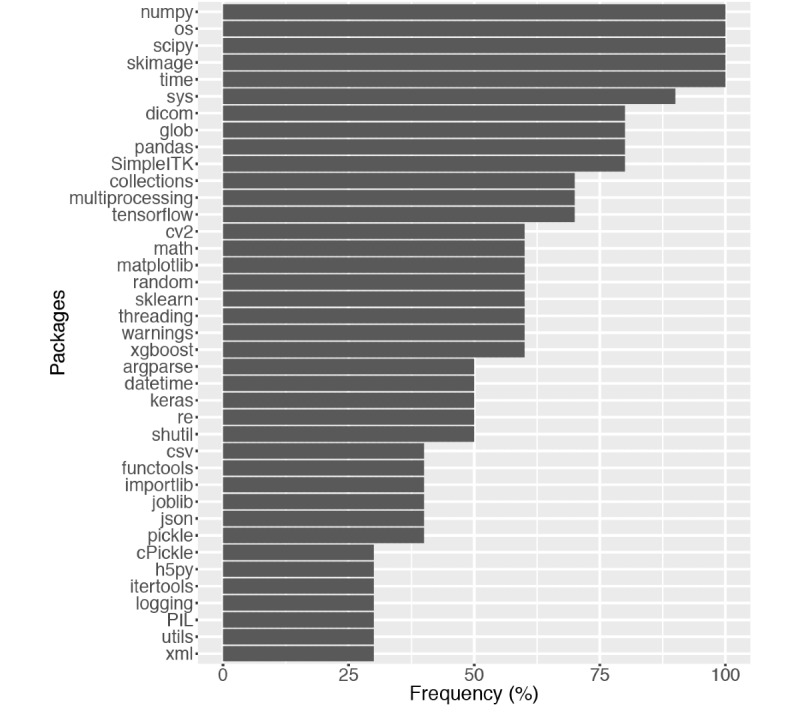

Most of the winning teams developed their modules with Keras and Tensorflow. Only one team used Pytorch (the top-performing team), Caffe, or Lasagne. All of the top 10 teams employed a number of python packages for scientific computing and image processing, including NumPy, SciPy, and Scikit-image (skimage). A summary of package dependencies is shown in Figure 4. This reflected the popularity of the tools for processing chest CT images, building neural networks, and scientific computing among the top contestants of this contest.

Figure 4.

The most widely used dependencies by the top 10 teams. The packages are ordered by their prevalence among the top teams. For simplicity, dependencies used by only one team are omitted from the figure.

Docker Images of the Top Solutions

To facilitate reusing the code developed by the top teams, we generated a Docker image for each of the available solutions. Our developed Docker images are redistributed under the open-source licenses chosen by the original developers [28]. Detailed instructions on accessing the Docker images can be found on GitHub [29].

Discussion

Principal Findings

This is the first study that systematically compared the algorithms and implementations of award-winning pulmonary nodule classifiers. Results showed that the majority of the best-performing solutions used additional datasets to train the pulmonary nodule segmentation models. The top solutions used different data preprocessing, segmentation, and classification algorithms. Nonetheless, they only differ slightly in their final test set scores.

The most commonly used data preprocessing steps were lung segmentation and voxel scaling [30]. For nodule classification, many solutions used CNNs. However, 2 of the top 10 teams employed tree-based methods for cancer versus noncancer classification. Tree-based approaches require a predefined set of image features, whereas CNNs allow data to refine the definition of features [31]. Given sufficient sample size, CNNs outperformed tree-based methods in many image-related tasks [12,32], whereas tree-based methods could reach satisfactory performance when the sample size was small, and they provided better model interpretability [33-35]. Since the conclusion of the contest, additional works on machine learning for CT evaluation have been published [36-40]. Nonetheless, these works reported similar strategies for data processing and classification overall.

To enhance the reproducibility of the developed modules, we generated a Docker image for each of the award-winning solutions. The Docker images contain all software dependencies and patches required by the source codes and are portable to various computing environments [16], which will expedite the application and improvement of the state-of-the-art CT analytical modules implemented by the contest winners.

Limitations

Since it was difficult to compile and release a large deidentified chest CT dataset to the public, the public test set only contains images from 198 patients. Leveraging the 5-digit precision of the log-loss value shown on the leaderboard, one participant implemented and shared a method for identifying all ground truth labels in the public test set during the competition [41]. Several participants successfully replicated this approach and got perfect scores on the public leaderboard. Thus, solutions with very low log-loss in the public test set may result from information leakage. Interestingly, among the top-10 models defined by the final test set, 2 performed worse than random guessing in the public test set, which raised concerns on their generalizability [42].

There are several approaches future contest organizers can take to ensure the generalizability of the developed models. First, a multistage competition can filter out the overfitted models using the first private test set and only allow reasonable models to advance to the final evaluation. In addition, organizers can discourage leaderboard probing by only showing the performance of a random subset of the public test data or limiting the number of submissions allowed per day. Finally, curating a larger test set can better evaluate the true model performance and reduce random variability [43]. If data deidentification is difficult, requiring contestants to submit their models to a secure computing environment rather than distributing the test data to the participants can minimize the risk of leaking identifiable medical information.

Conclusion

In summary, we compared, reproduced, and Dockerized state-of-the-art pulmonary nodule segmentation and classification modules. Results showed that many transfer learning approaches achieved reasonable accuracy in diagnosing chest CT images. Future works on additional data collections and validation will further enhance the generalizability of the current methods.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation to Dr Steven Seltzer for his feedback on the manuscript; Drs Shann-Ching Chen, Albert Tsung-Ying Ho, and Luke Kung for identifying the data resources; Dr Mu-Hung Tsai for pointing out the computing resources; and Ms Samantha Lemos and Nichole Parker for their administrative support. K-HY is a Harvard Data Science Fellow. This work was supported in part by the Blavatnik Center for Computational Biomedicine Award and grants from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (grant number OT3OD025466), and the Ministry of Science and Technology Research Grant, Taiwan (grant numbers MOST 103-2221-E-006-254-MY2 and MOST 103-2221-E-168-019). The authors thank the Amazon Web Services Cloud Credits for Research, Microsoft Azure Research Award, and the NVIDIA Corporation for their support on the computational infrastructure. This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment Bridges Pylon at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (through allocation TG-BCS180016), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (grant number ACI-1548562).

Abbreviations

- AAPM

American Association of Physicists in Medicine

- CNN

convolutional neural network

- CT

computed tomography

- LUNA16

Lung Nodule Analysis 2016

- ResNet

residual net

- skimage

Scikit-image

- SPIE

International Society for Optics and Photonics

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 Mar;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Sep 12;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, Gareen IF, Gatsonis C, Marcus PM, Sicks JD. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 4;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21714641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, Mazzone PJ, Midthun DE, Naidich DP, Wiener RS. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013 May;143(5 Suppl):e93S–e120S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2351. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23649456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam VK, Miller M, Dowling L, Singhal S, Young RP, Cabebe EC. Community low-dose CT lung cancer screening: a prospective cohort study. Lung. 2015 Feb;193(1):135–139. doi: 10.1007/s00408-014-9671-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moyer VA, U.S. Preventive Services Task Forsce Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Mar 4;160(5):330–338. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurcan MN, Sahiner B, Petrick N, Chan H, Kazerooni EA, Cascade PN, Hadjiiski L. Lung nodule detection on thoracic computed tomography images: preliminary evaluation of a computer-aided diagnosis system. Med Phys. 2002 Nov;29(11):2552–2558. doi: 10.1118/1.1515762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh SP, Gierada DS, Pinsky P, Sanders C, Fineberg N, Sun Y, Lynch D, Nath H. Reader variability in identifying pulmonary nodules on chest radiographs from the national lung screening trial. J Thorac Imaging. 2012 Jul;27(4):249–254. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e318256951e. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22627615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doi K. Computer-aided diagnosis in medical imaging: historical review, current status and future potential. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2007;31(4-5):198–211. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2007.02.002. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/17349778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin GD, Lyo JK, Paik DS, Sherbondy AJ, Chow LC, Leung AN, Mindelzun R, Schraedley-Desmond PK, Zinck SE, Naidich DP, Napel S. Pulmonary nodules on multi-detector row CT scans: performance comparison of radiologists and computer-aided detection. Radiology. 2005 Jan;234(1):274–283. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awai K, Murao K, Ozawa A, Komi M, Hayakawa H, Hori S, Nishimura Y. Pulmonary nodules at chest CT: effect of computer-aided diagnosis on radiologists' detection performance. Radiology. 2004 Feb;230(2):347–352. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2302030049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu K, Beam AL, Kohane IS. Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018 Oct;2(10):719–731. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0305-z. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0305-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Data Science Bowl 2017. Kaggle Inc. [2020-07-12]. https://www.kaggle.com/c/data-science-bowl-2017.

- 14.Healthcare 2020. Kaggle Inc. [2020-07-12]. https://www.kaggle.com/tags/healthcare.

- 15.About Docker. [2020-07-12]. https://www.docker.com/company.

- 16.Boettiger C. An introduction to Docker for reproducible research. SIGOPS Oper Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 20;49(1):71–79. doi: 10.1145/2723872.2723882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle DR, Berg CD, Black WC, Church TR, Fagerstrom RM, Galen B, Gareen IF, Gatsonis C, Goldin J, Gohagan JK, Hillman B, Jaffe C, Kramer BS, Lynch D, Marcus PM, Schnall M, Sullivan DC, Sullivan D, Zylak CJ. The National Lung Screening Trial: overview and study design. Radiology. 2011 Jan;258(1):243–253. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091808. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21045183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Data Science Bowl 2017: data description. Kaggle Inc. [2020-07-12]. https://www.kaggle.com/c/data-science-bowl-2017/data.

- 19.Open Source Initiative. [2020-07-12]. https://opensource.org/

- 20.Data Science Bowl 2017: rules. Kaggle Inc. [2020-07-12]. https://www.kaggle.com/c/data-science-bowl-2017/rules.

- 21.Setio AAA, Traverso A, de Bel T, Berens MS, Bogaard CVD, Cerello P, Chen H, Dou Q, Fantacci ME, Geurts B, Gugten RVD, Heng PA, Jansen B, de Kaste MM, Kotov V, Lin JY, Manders JT, Sóñora-Mengana A, García-Naranjo JC, Papavasileiou E, Prokop M, Saletta M, Schaefer-Prokop CM, Scholten ET, Scholten L, Snoeren MM, Torres EL, Vandemeulebroucke J, Walasek N, Zuidhof GC, Ginneken BV, Jacobs C. Validation, comparison, and combination of algorithms for automatic detection of pulmonary nodules in computed tomography images: the LUNA16 challenge. Med Image Analysis. 2017 Dec;42:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2017.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armato SG, McLennan G, Bidaut L, McNitt-Gray MF, Meyer CR, Reeves AP, Zhao B, Aberle DR, Henschke CI, Hoffman EA, Kazerooni EA, MacMahon H, Van Beeke EJR, Yankelevitz D, Biancardi AM, Bland PH, Brown MS, Engelmann RM, Laderach GE, Max D, Pais RC, Qing DPY, Roberts RY, Smith AR, Starkey A, Batrah P, Caligiuri P, Farooqi A, Gladish GW, Jude CM, Munden RF, Petkovska I, Quint LE, Schwartz LH, Sundaram B, Dodd LE, Fenimore C, Gur D, Petrick N, Freymann J, Kirby J, Hughes B, Casteele AV, Gupte S, Sallamm M, Heath MD, Kuhn MH, Dharaiya E, Burns R, Fryd DS, Salganicoff M, Anand V, Shreter U, Vastagh S, Croft BY. The Lung Image Database Consortium (LIDC) and Image Database Resource Initiative (IDRI): a completed reference database of lung nodules on CT scans. Med Phys. 2011 Feb;38(2):915–931. doi: 10.1118/1.3528204. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21452728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armato SG, Drukker K, Li F, Hadjiiski L, Tourassi GD, Engelmann RM, Giger ML, Redmond G, Farahani K, Kirby JS, Clarke LP. LUNGx Challenge for computerized lung nodule classification. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 2016 Oct;3(4):044506. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.3.4.044506. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28018939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Navab N, Hornegger J, Wells W, Frangi A, editors. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 9351. Cham: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2014:14091556. [Google Scholar]

- 26.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016; Las Vegas. 2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin H, Roth HR, Gao M, Lu L, Xu Z, Nogues I, Yao J, Mollura D, Summers RM. Deep convolutional neural networks for computer-aided detection: CNN architectures, dataset characteristics and transfer learning. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2016 May;35(5):1285–1298. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2016.2528162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DockerHub. [2020-07-12]. https://rebrand.ly/chestct.

- 29.Docker images for chest CT analyses. [2020-07-12]. https://github.com/khyu/dsb_chestct.

- 30.Lifton J, Malcolm A, McBride J, Cross K. The application of voxel size correction in X-ray computed tomography for dimensional metrology. 2013. [2020-07-12]. https://www.ndt.net/article/SINCE2013/content/papers/24_Lifton.pdf.

- 31.Yu K, Wang F, Berry GJ, Ré C, Altman RB, Snyder M, Kohane IS. Classifying non-small cell lung cancer types and transcriptomic subtypes using convolutional neural networks. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 May 01;27(5):757–769. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russakovsky O, Deng J, Su H, Krause J, Satheesh S, Ma S, Huang Z, Karpathy A, Khosla A, Bernstein M, Berg AC, Fei-Fei L. ImageNet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int J Comput Vis. 2015 Apr 11;115(3):211–252. doi: 10.1007/s11263-015-0816-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu K, Berry GJ, Rubin DL, Ré C, Altman RB, Snyder M. Association of omics features with histopathology patterns in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Syst. 2017 Dec 27;5(6):620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.10.014. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405-4712(17)30484-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu K, Zhang C, Berry GJ, Altman RB, Ré C, Rubin DL, Snyder M. Predicting non-small cell lung cancer prognosis by fully automated microscopic pathology image features. Nat Commun. 2016 Dec 16;7:12474. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12474. https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms12474#supplementary-information. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu K, Fitzpatrick MR, Pappas L, Chan W, Kung J, Snyder M. Omics AnalySIs System for PRecision Oncology (OASISPRO): a web-based omics analysis tool for clinical phenotype prediction. Bioinformatics. 2018 Jan 15;34(2):319–320. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx572. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28968749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishio M, Sugiyama O, Yakami M, Ueno S, Kubo T, Kuroda T, Togashi K. Computer-aided diagnosis of lung nodule classification between benign nodule, primary lung cancer, and metastatic lung cancer at different image size using deep convolutional neural network with transfer learning. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200721. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.da Silva GLF, Valente TLA, Silva AC, de Paiva AC, Gattass M. Convolutional neural network-based PSO for lung nodule false positive reduction on CT images. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2018 Aug;162:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ait Skourt B, El Hassani A, Majda A. Lung CT image segmentation using deep neural networks. Procedia Comput Sci. 2018;127:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2018.01.104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lakshmanaprabu S, Mohanty SN, Shankar K, Arunkumar N, Ramirez G. Optimal deep learning model for classification of lung cancer on CT images. Future Gen Comput Syst. 2019 Mar;92:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2018.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie H, Yang D, Sun N, Chen Z, Zhang Y. Automated pulmonary nodule detection in CT images using deep convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognition. 2019 Jan;85:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2018.07.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trott O. The Perfect Score script. 2017. [2020-05-24]. https://www.kaggle.com/olegtrott/the-perfect-score-script.

- 42.Yu K, Kohane IS. Framing the challenges of artificial intelligence in medicine. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 Mar;28(3):238–241. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brain D, Webb GI. On the effect of data set size on bias and variance in classification learning. 1999. [2020-07-12]. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6daf/14076a7ad2c4b4f1a8eb28778b9c641777e7.pdf.