Abstract

Collagen is a rich source of bioactive peptides and is widely distributed in the skin and bone tissue. In this study, collagen from Salmo salar skin was hydrolyzed with Alcalase or Protamex followed by simulated digestion, YMC ODS-A C18 separation, and ESI-MS/MS analysis. A total of 19 peptides were identified and synthesized for investigation of their antiplatelet activities. Hyp-Gly-Glu-Phe-Gly (OGEFG) and Asp-Glu-Gly-Pro (DEGP) exhibited the most potent activity against ADP-induced platelet aggregation among them with IC50 values of 277.17 and 290.00 μM, respectively, and inhibited the release of β-TG and 5-HT in a dose-dependent manner significantly. Single oral administration of OGEFG and DEGP also inhibited thrombus formation in a ferric chloride-induced arterial thrombosis model at a dose of 200 μmol/kg body weight and did not prolong the bleeding time or cause an immune response in mice. Therefore, our findings indicated that collagen peptides had a potential to be developed into an effective specific medical food in the prevention of thrombotic diseases.

Introduction

It has been widely accepted that platelet aggregation and activation play an important role in the pathogenesis of thrombosis, including acute arterial thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis, and coronary thrombosis, according to the pathophysiological mechanisms.1 In the resting state, platelets are discoid and inactive. When vascular damage occurs, the locally exposed collagen and thrombin will activate platelets to produce ADP and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) to maintain continuous platelet activation. In general, the activation of platelets induced by agonists begins with the activation of the phospholipase C (PLC) isoforms expressed in platelets followed by the increase of Ca2+ concentration, causing the conformational change of the cell skeleton. Ultimately, subsequent intracellular signaling activates integrin αIIbβ3 on the platelet surface, thereby enabling platelet aggregation and adhesion. This process is mainly mediated by the interaction between the integrin receptor αIIbβ3 of activated platelets and fibrinogen, which leads to the formation of platelet-rich thrombus.2

Accordingly, the development of antiplatelet drugs that block platelet activation and aggregation will provide excellent therapeutic strategies to treat and prevent thrombotic diseases clinically. However, current antiplatelet drugs are still limited for their side effects, especially bleeding complications. Additionally, the latest study has shown that the use of low-dose aspirin as a primary prevention strategy in elder adults resulted in a significantly higher risk of major hemorrhage and did not result in a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular disease than the placebo.3 It is also observed that daily aspirin prevention leads to a higher all-cause mortality than placebo prevention among healthy elder adults.4 Thus, it is essential to develop new agent that is more potent and safer in the prevention of thrombotic diseases.

Bioactive peptides, whose molecular sizes range from 2 to 20 amino acid residues released by enzymatic hydrolysis by proteinases and peptidases, are usually related to reduced incidence of negative side effects and low toxicity5 and have been widely investigated with an antiplatelet aggregation activity. However, few peptides with an antiplatelet activity were identified from the food source, such as the tripeptide SQL from centipedes,6 YY-39 from tick salivary glands,7 RGD from fibrinogen α chains,8 and AAP from venom.9 As a consequence, it would be difficult to be utilized in industrial production of special medical food for the prevention of thrombosis because of their limitation on raw materials.

Our previous study has shown that oral administration of collagen hydrolysates could downregulate nine cytokines significantly, which were highly expressed in activated platelets.10 However, the active peptides and their antiplatelet activities remained unknown. The objection of this study was to investigate the peptide sequence of the collagen hydrolysate with a higher inhibitory activity against platelet aggregation in vitro and the in vivo antithrombosis activity as well as potential side effects.

Results

Hydrolysis of Collagen

To produce antiplatelet aggregation peptides from collagen, enzymatic hydrolysis was performed using Alcalase or Protamex under optimal conditions for 4 h. Then, the hydrolysates were further digested by pepsin and pancreatin to simulate gastrointestinal digestion. The degree of hydrolysis (DH) was employed to monitor the state and rate of proteolysis. As shown in Figure 1A, DH increased gradually with the increase of reaction time. The hydrolysis curve of Alcalase increased slightly after 2 h (DH = 17.90%) with a maximum DH of 19.82% at 4 h. Similar results were found for Protamex with a maximum DH of 20.05% at 4 h. DH was not altered significantly after two-hour pepsin hydrolysis but increased to 24.95 and 26.90% for Alcalase and Protamex, respectively. Evidence of proteolysis is shown through the result of molecular weight distribution of collagen hydrolysates. As shown in Figure 1B, the major molecular weights were less than 1000 Da, indicating that the majority of collagen was hydrolyzed into oligopeptides. After pepsin and pancreatin (PP) digestion, more small peptides were released, especially those in the <500 Da ranges. Inhibitory activities against platelet aggregation of Alcalase hydrolysates (AH) (40.40%) and Protamex hydrolysates (PH) (35.63%) were shown as an insert in Figure 1A. Interestingly, the inhibitory rate increased to 60.57 and 56.51% for both AH and PH after PP digestion, respectively.

Figure 1.

(A) Degree of hydrolysis of Alcalase and Protamex collagen hydrolysates followed by pepsin and pancreatin (PP) digestion at various time points. (B) Molecular weight (MW) distribution of the collagen hydrolysate.

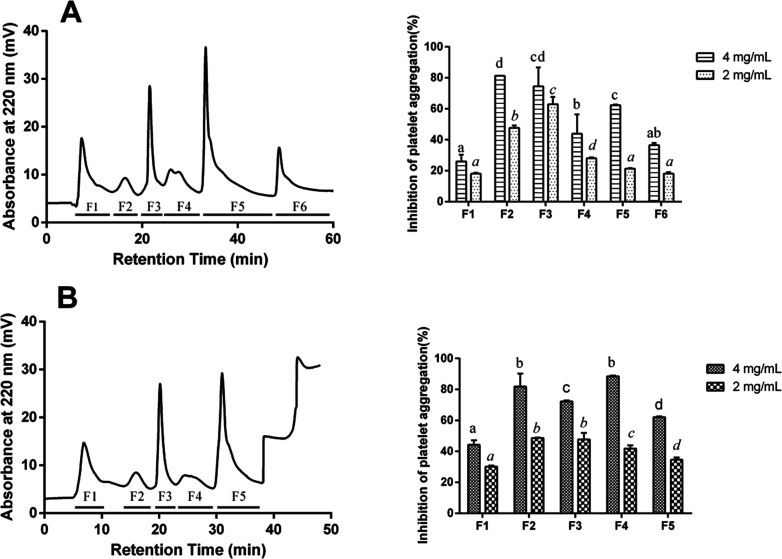

Separation and Identification of Antiplatelet Collagen Peptides

To identify the collagen peptides (CPs) with a higher antiplatelet aggregation activity, the hydrolysates after simulated gastrointestinal digestion were used for further separation. As shown in Figure 2, all the peptides were eluted out around 60 min and were then separated into six fractions (AH-PP-F1–F6) and five fractions (PH-PP-F1–F5), respectively. The inhibitory effects against platelet aggregation in vitro were widely observed in all the fractions, suggesting that different CPs with different hydrophobicity, which was direct related to retention time, had an antiplatelet activity in collagen hydrolysates. The fraction AH-PP-F3 exhibited the highest (p < 0.05) level of antiplatelet aggregation activity with 62.93% at 2 mg/mL, and the fraction AH-PP-F2 showed the highest activity (81.26%) at 4 mg/mL. A similar result was shown in the fraction PH-PP-F4 with 88.52% at 4 mg/mL and fraction PH-PP-F2 with 48.69% at 2 mg/mL. Thus, these four fragments were selected for peptide identification and amino acid sequence analysis.

Figure 2.

Separation of (A) Alcalase and (B) Protamex collagen hydrolysates after simulated gastrointestinal digestion by a YMC ODS-A C18 column and corresponding inhibition of platelet aggregation induced by ADP of collagen hydrolysate fractions from C18 separation at 2 and 4 mg/mL, respectively. Bars (mean ± SD, n = 3) with different alphabets have mean values that are significantly different (p < 0.05).

The amino acid sequences of CPs were identified using HPLC-ESI-MS/MS and calculated by de nova sequencing.11 The mass spectra of four collagen hydrolysate fragments are shown in Figure 3, the detailed information of the peptide sequence is shown in Table 1, and the interpretation of the MS/MS spectra for OGEFG and DEGP is exhibited in Figure 3E,F. The parent ion 417.16 m/z was identified as the peptide DEGP calculated by y-type ions. Similarly, the parent ion 522.22 m/z identified the peptide as OGEFG, which was calculated by b-type ions. The other peptides were also calculated accordingly, and the results are shown in Table 1; a total of seven peptides were identified in AH-PP-F3 and four peptides in AH-PP-F2, while a total of five peptides were identified in PH-PP-F4 and seven peptides in PH-PP-F2, according to the identified collagen sequence from protein database on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

Figure 3.

ESI mass spectrum of collagen peptides present in (A) AH-PP-F2, (B) AH-PP-F3, (C) PH-PP-F2, and (D) PH-PP-F4. MS/MS spectrum of peptides (E) OGEFG (521.26 Da) and (F) DEGP (416.16 Da).

Table 1. Identification of Collagen Peptide Sequences from Four Fragments by ESI-MS/MS.

| fraction | AA Sequence | m/z | protein fragmenta |

|---|---|---|---|

| A + PP-F2 | QGO | 317.24 | frequency = 11 |

| A + PP-F2 | PGGO | 343.20 | f(1319–1322) |

| A + PP-F3 | PLD | 344.23 | f(319–321), f(351–353) |

| A + PP-F3 | FPQ | 391.18 | f(288–290) |

| A + PP-F3 | DEGP | 417.18 | f(670–673), f(811–814) |

| A + PP-F3 | PGYV | 435.21 | f(644–647) |

| A + PP-F3 | RPW | 458.22 | f(421–423) |

| A + PP-F3 | WGPR | 515.25 | f(236–239) |

| P + PP-F2 | PA | 187.14 | frequency = 9 |

| P + PP-F2 | TP | 217.11 | frequency = 6 |

| P + PP-F2 | SPGO | 373.69 | frequency = 3 |

| P + PP-F2 | ROR | 444.22 | f(165–167) |

| P + PP-F2 | OTGPK | 515.25 | f(571–575) |

| P + PP-F4 | PGA | 244.13 | f(1145–1147), f(1536–1538) |

| P + PP-F4 | SHE | 372.19 | f(282–284) |

| P + PP-F4 | VFPQ | 490.73 | f(287–290) |

| P + PP-F4 | OGEFG | 522.22 | f(709–713) |

| A + PP-F2/F3, P + PP-F2/F4 | ME | 279.16 | f(1601–1602) |

| A + PP-F2, P + PP-F2 | WPR | 458.23 | f(526–528) |

Indicated that the sequence was from Salmo salar collagen α (I/II) chain in NCBI.

Inhibitory Effects of CPs on Platelet Aggregation and Granule Release In Vitro

For further investigation of the inhibitory effect on platelet activation of CPs, the above identified peptides were synthesized for IC50 values against ADP-induced platelet aggregation in vitro. As shown in Figure 4A, the CPs inhibited ADP-induced platelet aggregation. The peptide WGPR exhibited the strongest inhibitory activity among them with an IC50 value of approximately 208.70 μM followed by SHE (213.70 μM), OGEFG (277.17 μM), and DEGP (290.00 μM). However, the other peptides including PA, TP, ROR, WPR, VFPQ, PGA, and FPQ exhibited poor activities against ADP-induced platelet aggregation (data not shown). Additionally, the peptide ME was abundant in all these four fractions and also exhibited a potent antithrombosis activity (unpublished data). For further evaluating the antiplatelet aggregation activities, thrombin as a potent agonist was employed to stimulate platelet activation, and the result is shown in Figure 4B. Interestingly, the peptide OGEFG exhibited the strongest activity against thrombin-induced platelet aggregation with an IC50 value of 1.612 mM. The IC50 values of the other peptides were slightly higher than that of OGEFG, and the order was DEGP (1.979 mM), WGPR (2.848 mM), and SHE (3.023 mM). However, the IC50 values of the other peptides were over 4 mM (data not shown). This result was in contrast with that of ADP-induced platelet aggregation. Additionally, ADP played a critical role in the signal magnifier during platelet activation, which was a weaker agonist than thrombin. Thus, the peptides OGEFG and DEGP were selected for further investigation of their in vivo antithrombosis activities.

Figure 4.

IC50 values of antiplatelet aggregation effects of CPs induced by (A) ADP and (B) thrombin. The effects of CPs on the release of 5-HT-induced by (C) ADP and (D) thrombin as well as (E) β-TG for ADP and (F) thrombin. Bars (mean ± SD, n = 3) with different alphabets have mean values that are significantly different (p < 0.05). *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, as compared to the control group.

β-TG and 5-HT were the landmarks of the release of α-granules and dense granules. The results are shown in Figure 4C–F; the peptides OGEFG and DEGP inhibited the release of β-TG and 5-HT in a dose-dependent manner significantly (p < 0.05) when the platelet was stimulated by thrombin and ADP.

CPs Inhibited Arterial Thrombus Formation In Vivo

To evaluate the antithrombosis activities of CPs in vivo, a ferric chloride-induced arterial thrombosis model in rats was employed. The results are shown in Figure 5 wherein the peptide OGEFG could inhibit the thrombus formation significantly at doses of 200 and 300 μmol/kg body weight (b.w.) by 46.7 and 43.3%, respectively (p < 0.05). Similar results were shown in the peptide DEGP that dose dependence inhibited thrombosis by 53.3 and 62.3% accordingly. At a recommended daily dose (65 μmol/kg b.w.), the thrombus weight of the aspirin-treated group and clopidogrel-treated group decreased by 65.0 and 61.2%, respectively, which were similar to that of the peptide DEGP at a high dose.

Figure 5.

Effects of CPs OGEFG and DEGP on ferric chloride-induced arterial thrombosis model rats. Male Sprague Dawley rats were orally administrated with 0.9% saline, clopidogrel, aspirin, OGEFG, or DEGP at different doses (μmol/kg b.w.), respectively. Bars (mean ± SD, n = 6) with different alphabets have mean values that are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Effects of CPs on Bleeding Time (BT)

The effects of CPs on BT were measured to evaluate the bleeding risk. As shown in Figure 6A, the CPs OGEFG and DEGP exhibited no significant increase in BT at doses of 300 and 400 μmol/kg b.w. However, the clopidogrel-treated group prolonged the BT significantly with BT > 15 min (p < 0.001). A similar result was found in the aspirin-treated group with a BT of 5.345 min, which was much longer than that of CP-treated groups at a lower dose (p < 0.01). This result indicated that the CPs showed no bleeding risk at the effective dosage, and their bleeding risk was much lower than that of clopidogrel or aspirin.

Figure 6.

Effects of CPs OGEFG and DEGP on (A) BT and (B) thymus index and spleen index in mice. Male ICR mice were orally administrated with 0.9% saline, clopidogrel, aspirin, OGEFG, or DEGP at different doses (μmol/kg b.w.), respectively. ** and *** indicate p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively, as compared to the vehicle group.

Effects of CPs on the Thymus Index (TI) and Spleen Index (SI) In Vivo

The TI and SI of mice after CP treatment were measured to preliminarily investigate whether the CPs or CP dose had obvious toxicological effects on the animal subjects.12 As shown in Figure 6B, the TI and SI of the OGEFG-, DEGP-, clopidogrel-, and aspirin-treated groups had no significant difference compared to that of the vehicle group. There was no obvious atrophy and hyperplasia or swelling of thymus and spleen. Thus, it could be concluded that oral administration of the CPs OGEFG and DEGP at doses of 300 or 450 μmol/kg b.w. had no acute toxicological effects.

Discussion

The biological processes of platelet adhesion, activation, and aggregation played a vital role in the process of primary hemostasis as well as the formation of an occlusive thrombus. Due to the high turnover of the platelet in the body and its essential role in hemostasis and thrombosis, the platelet has long been a primary target for therapeutic intervention for the prevention of occlusive thrombotic events. Our previous study has shown that the collagen hydrolysates after oral administration could downregulate nine cytokines significantly in elder mice, which were highly expressed in an activated platelet,10 and then inhibited the activation of the platelet. However, the peptide sequence with an inhibitory activity against platelet aggregation remains unknown. Based on these observations that the bioactive potency was released after oral administration, enzymolysis followed by gastrointestinal digestion were employed to simulate in vivo absorption of collagen hydrolysate to prepare collagen peptides with antiplatelet aggregation or an antithrombosis activity. Alcalase is an endopeptidase and widely used in protein hydrolysis commercially. Alcalase acted on the intramolecular peptide bond and had a preference for Ala, Leu, Val, Tyr, and Phe sequences,13 while Protamex worked on the peptide bond at the end of the peptide chain. A previous study has also shown that Alcalase hydrolysates released from grain protein exhibited antiplatelet activities.14 Pepsin preferred to cleavage Phe, Tyr, and Ala whose cleavage sites were similar to Alcalase. Consequently, no significant alternation of DH was observed after pepsin hydrolysis. However, the DH increased significantly after pancreatin digestion for its cleavage sites of Arg and Lys. These results were confirmed by molecular weight distribution that more CPs with a smaller molecular weight were released after simulated digestion. Interestingly, the collagen hydrolysates after simulated digestion exhibited a higher inhibitory activity against ADP-induced platelet aggregation. The DH observed in this work was more than values reported for silver carp protein hydrolysate (8.1%).15

Platelet aggregation could be induced by various agonists and mainly amplified by ADP that was released from platelet granules.16 Recent studies have suggested that the ADP receptor inhibitor may be a better choice for secondary prevention in patients with atherosclerotic ischemic stroke subtypes because of its multiple functions, such as anti-atherosclerotic,17 antiplatelet aggregation,18,19 and neuroprotective activities.20 Therefore, development of biopeptides that could inhibit ADP-induced platelet aggregation and activation could be more advantageous than other antiplatelet agents. A previous study has shown that the pepsin hydrolysates of gelatin from mackerel skin could inhibit the ADP secretion during platelet aggregation.21 However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a scanty report on the antiplatelet peptides, especially identified from food resources, and the activity was relatively lower than that of other peptides usually identified from snake venom. In the present study, the IC50 values of antiplatelet aggregation activities induced by ADP were 277.17 and 290.00 μM for CPs OGEFG and DEGP, respectively. Actually, the identified peptides were synthesized in the form of acetate for the animal experiment, which may contribute to the increase of molecular weight. As a consequence, the effective sequence of the peptide itself was decreased at the same concentration, which would lead to the impaired antiplatelet aggregation activity. The tested peptides exhibited a higher in vitro antiplatelet aggregation activity when compared with these reported peptides, such as SQL that inhibited human platelet aggregation by 20.2% at 2.89 mM22 as well as LTFPRIVFVLG by 76.69% at 1 mg/mL.23 On the other hand, the characteristics of the antiplatelet peptide sequence remain unknown. A previous study has reported that hydrophilic peptides SSGE and DGE exhibited an antiplatelet activity induced by ADP with IC50 values of 0.48 and 0.46 mM, respectively.24 The identified peptides in our study, including OGEFG, DEGP, PGYV, PGGO, OTGPK, SPGO, and QGO, were less than six amino acids in length and contained hydroxyproline, which was the hydroxylation of proline and unique to collagen. In addition, acidic amino acids, such as Asp and Glu, and the basic amino acid Lys were also contained. These amino acid compositions might contribute to a higher inhibitory activity against ADP-induced platelet aggregation and activation. The Pro-Gly (PG) or Gly-Pro (GP) motif was also observed in these peptides, and all these peptides exhibited an antiplatelet activity induced by ADP. Similarly, a previous study has also shown that the tripeptide PGP, which contained a PG or GP motif, could suppress the thrombus formation by the anticoagulation effect.25 Moreover, the release of β-TG and 5-HT were also impaired with the incubation of PG- or GP-containing peptides OGEFG and DEGP. However, the antiplatelet mechanism of collagen peptides remains unknown, and more study should concentrate on the relationships between the specific sequence and antiplatelet activities. Based on these observations, it could be speculated that the PG or GP motif in peptides might play an important role in the inhibition of further activation and coagulation of platelets after ADP or thrombin stimulation.

The ferric chloride-induced arterial thrombosis model is a classic assay used widely to investigate the antithrombotic activities of an antiplatelet compound in vivo under the condition of vascular injury.26,27 The present study showed that oral administration of peptides OGEFG and DEGP decreased the thrombus weight significantly whose effects were comparable with aspirin and clopidogrel at a one-third dose approximately. However, the benefit–risk balance between the antithrombosis activity and side effects, such as bleeding risk and immune response, is extremely important for the development of antiplatelet agents. Thus, the BT in mice and immune parameters were also determined to investigate the potential side effects. Interestingly, the antithrombosis drug clopidogrel prolonged the BT (>15 min) significantly at a one-third dose of CPs OGEFG and DEGP. A similar result was also observed in aspirin with a little bleeding risk. Additionally, the TI and SI were not altered after CP treatment with a reduced risk to cause an immune response. These results of an in vivo antithrombosis activity and side effect demonstrated that the CPs OGEFG and DEGP may have potential to be used as natural additives in the prevention of thrombosis. Further study should concentrate on the mechanism of CPs to inhibit the platelet activation.

Conclusions

Taken together with these results of the current study, it could be concluded that the CPs could effectively inhibit platelet aggregation induced by ADP in vitro and exert potent antithrombosis activities in vivo without bleeding risks. The peptides OGEFG and DEGP were the most active components in CPs against platelet aggregation. Similar peptides were also identified with IC50 values less than 0.5 mM, indicating that PG- or GP-containing peptides might be the main effective peptides in CPs. Further study is necessary to investigate other peptide families containing this motif and their antithrombosis mechanisms. The present study demonstrated that the CPs may have potential to be developed as an effective and safe agent to prevent the occurrence of thrombotic diseases.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

Alcalase and Protamex were purchased from Novozymes Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The 5-HT ELISA kit was purchased from IBL international (German). The β-TG ELISA kit was obtained from Cloud-Clone Corp (Wuhan, China). Thrombin and ADP were purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Aspirin and clopidogrel hydrogen sulfate were purchased from MCE (Shanghai, China). Other chemicals used were analytical grade or better.

Preparation of Collagen Hydrolysates

Briefly, the thawed Salmo salar skin was firstly treated in 0.05 M NaOH and then in 0.2% H2S04 (1:6, w/v) at room temperature for 60 min. After the acid treatment, the swollen skins were soaked in distilled water at 45 °C for 12 h to extract gelatin. The resultant gelatin was enzymatically hydrolyzed using the following enzyme, and reaction conditions were reported as previous: Alcalase (pH 8.0, 60 °C) and Protamex (pH 7.5, 55 °C). Enzymatic hydrolysis was performed for 4 h (pH maintained constantly by addition of NaOH) followed by simulated digestion with pepsin (pH 2.0, E/S = 1:50) and pancreatin (pH 7.0, E/S = 1: 50), after which the enzymes were inactivated by immersing the reaction vessel in a boiling water bath for 10 min. After centrifugation at 12000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and lyophilized to make collagen hydrolysates for further analysis.

Degree of Hydrolysis

The time-dependent changes of DH during enzymatic hydrolysis were determined by the TNBS method.28 The DH was calculated according to the following equation

where h is the concentration in milliequivalents of protein of α-NH2 formed during hydrolysis (mmol/mL), and htot refers to the hydrolysis equivalent at complete hydrolysis to amino acids. For collagen hydrolysates, htot is 8.41.

Molecular Weight (MW) Distribution

MW distribution of each fraction was determined by HPLC with a TSK gel G2000 SWXL column.29 The calibration curve was obtained by fitting the retention time and logarithm of MW of the following standards: aprotinin (6512 Da), bacitracin (1423 Da), YPWY (627 Da), CLC (338 Da), and Gly-Sar (146 Da). The MW distributions of peptide fractions were calculated according to the calibration curve.

Separation and Purification of Collagen Hydrolysates

The lyophilized collagen hydrolysates were dissolved in water (100 mg/mL), and the solution was then applied to a YMC ODS-A C18 column (Φ 1.0 cm × 10 cm). The elution program was as follows: 0–13 min, water; 13–26 min, 10% methanol; 26–40 min, 30% methanol; 40–60 min, 50% methanol. The flow rate was controlled at 1.0 mL/min by a constant flow pump. The eluent was monitored at 220 nm by an HD-A chromatography data handling system (Shanghai Qingpu Huxi Instruments, Shanghai, China). The fractions were collected, lyophilized, and tested for an antiplatelet aggregation activity.

Identification of Collagen Peptides

The most active peptide fractions against ADP-induced platelet aggregation from the column separation were each dissolved in water and loaded onto an Acclaim PepMap RPLC C18 column (7.5 μm i.d. × 150 mm) for HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis with an injection volume of 10 μL and flow rate of 0.3 μL/min. The elution program was performed as follows: 0–5 min, 6%–9% buffer B (0.1% formic acid in 80% ACN); 5–50 min, 9%–50% buffer B; 50–52 min, 50%–95% buffer B; 52–56 min, 95% buffer B. The scan range of MS/MS was from 50 to 1500 m/z. Peptide sequences obtained from the MS/MS spectra were confirmed using protein database from NCBI. Predicated peptides were synthesized with a purity of >98% by GL Biochem (Shanghai, China).

Animal Model and Environmental Conditions

The male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (280–300 g) and Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice (28 ± 2 g) were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing China). The rats or mice were acclimatized for a week in a pathogen-free animal housing under a 12 h-day-and-night cycle at 21 °C with access to a regular chow diet and tap water. All experiments involving animals were performed in compliance with the relevant laws and institutional guidelines with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Preparation of the Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) and Washed Platelet

The platelet was isolated from rat aorta blood and mixed with sodium citrate (1:9, v/v) as previously described with some modifications.30 Briefly, anticoagulated blood was centrifuged (50 × g, 10 min) to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP). The residue was centrifuged at 750 × g for 10 min to collect the platelet-poor plasma (PPP), and PRP was diluted to 2–3 × 108 with PPP. The washed platelet was obtained by washing with an HEPES/Tyrode buffer (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 5.56 mM glucose, 12 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 0.36 mM NaH2PO4·H2O, and pH 7.4) containing 0.5 mM EGTA (ethylene glycol tetra-acetic acid). The washed platelets were resuspended in the HEPES/Tyrode buffer and adjusted to 2–3 × 108 cells/mL.

Antiplatelet Aggregation In Vitro

Inhibition of platelet aggregation induced by ADP and thrombin was measured with a four-channel aggregometer as previously described.31 Aliquots of 270 μL of washed platelet were incubated with 30 μL of the HEPES/Tyrode buffer or the CPs with different concentration at 37 °C for 5 min, respectively. After incubation, platelet aggregation was induced by adding 30 μL of thrombin (0.5 U/mL). For platelet aggregation induced by ADP (0.1 mM), PRP was used to replace the washed platelet for determination. The platelet aggregation at 5 min was recorded, and the inhibition rate was calculated as follows

inhibition of platelet aggregation (%) = [1 – platelet aggregation (sample)/platelet aggregation (control)] × 100

The IC50 value of platelet aggregation was calculated by Graphpad Prism 6.0.

ELISA Analysis

The 5-HT and β-TG were determined according to the corresponding ELISA kit instructions. Briefly, aliquots of 270 μL of PRP were incubated with 30 μL of the HEPES/Tyrode buffer or the CPs at 37 °C for 5 min. After stimulation with ADP, the reaction was stopped by an ice bath and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 2 min. The supernatant was used for ELISA analysis.

Ferric Chloride-Induced Arterial Thrombosis Model

To estimate the effects of the CPs on thrombus formation in vivo, a ferric chloride-induced arterial thrombosis model in rats was used according to the described method6 with some modification. SD rats were randomly divided into 7 groups (n = 6) and orally administrated with the vehicle (saline), OGEFG (200 and 300 μmol/kg, bw), DEGP (200 and 300 μmol/kg, bw), clopidogrel (65 μmol/kg, bw), or aspirin (65 μmol/kg, bw), respectively. After 1 h, the vascular injuries were induced by applying a filter paper (5 × 10 mm) saturated with 25% ferric chloride on the adventitial surface of the exposed left common carotid arteries. The injured carotid artery segment was excised, and the thrombus was washed carefully with PBS. After blotting the excess liquid, the thrombus was weighed immediately.

Tail Bleeding Assay in Mice

To evaluate the bleeding risk of the CPs, a modified tail-cutting method was employed.32 The mice were grouped (n = 10), and the vehicle, OGEFG (300 and 450 μmol/kg, bw), DEGP (300 and 450 μmol/kg, bw), aspirin (100 μmol/kg, bw), or clopidogrel (100 μmol/kg, bw) were orally administrated. The mouse tail was marked with a tag in a distance of 3 mm from the tail tip and then cut in the mark. The tip of the tail was immediately dipped into saline at 37 °C. Blood flowing from the incision was carefully monitored, and the time interval from cutting the tail tip to stopping bleeding was recorded as the bleeding time (BT) with a maximum of 900 s.

Determination of Thymus Index and Spleen Index

The ICR mice after the tail bleeding experiment were weighed immediately and sacrificed. The thymus and spleen were excised from the mice and washed with PBS. After blotting the excess liquid, the thymus and spleen were weighed immediately, and the TI and SI were calculated according to the following equation: TI/SI (mg/g) = (weight of thymus/spleen)/mouse body weight.

Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. The statistical significance was assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Ducan’s tests using SPSS 19.0. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD0901102) and by the earmarked fund from China Agriculture Research System (CARS-45).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Yeung J.; Li W.; Holinstat M. Platelet Signaling and Disease: Targeted Therapy for Thrombosis and Other Related Diseases. Pharmacol. Rev. 2018, 70, 526–548. 10.1124/pr.117.014530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilahur G.; Gutiérrez M.; Arzanauskaite M.; Mendieta G.; Ben-Aicha S.; Badimon L. Intracellular platelet signalling as a target for drug development. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2018, 111, 22–25. 10.1016/j.vph.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil J. J.; Wolfe R.; Woods R. L.; Tonkin A. M.; Donnan G. A.; Nelson M. R.; Reid C. M.; Lockery J. E.; Kirpach B.; Storey E.; Shah R. C.; Williamson J. D.; Margolis K. L.; Ernst M. E.; Abhayaratna W. P.; Stocks N.; Fitzgerald S. M.; Orchard S. G.; Trevaks R. E.; Beilin L. J.; Johnston C. I.; Ryan J.; Radziszewska B.; Jelinek M.; Malik M.; Eaton C. B.; Brauer D.; Cloud G.; Wood E. M.; Mahady S. E.; Satterfield S.; Grimm R.; Murray A. M.; Effect of Aspirin on Cardiovascular Events and Bleeding in the Healthy Elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1509–1518. 10.1056/NEJMoa1805819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil J. J.; Nelson M. R.; Woods R. L.; Lockery J. E.; Wolfe R.; Reid C. M.; Kirpach B.; Shah R. C.; Ives D. G.; Storey E.; Ryan J.; Tonkin A. M.; Newman A. B.; Williamson J. D.; Margolis K. L.; Ernst M. E.; Abhayaratna W. P.; Stocks N.; Fitzgerald S. M.; Orchard S. G.; Trevaks R. E.; Beilin L. J.; Donnan G. A.; Gibbs P.; Johnston C. I.; Radziszewska B.; Grimm R.; Murray A. M.; Effect of Aspirin on All-Cause Mortality in the Healthy Elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1519–1528. 10.1056/NEJMoa1803955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aluko R. E. Antihypertensive Peptides from Food Proteins. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 6, 235–262. 10.1146/annurev-food-022814-015520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X.-L.; Su W.; He Z.-L.; Ming X.; Kong Y. Tripeptide SQL Inhibits Platelet Aggregation and Thrombus Formation by Affecting PI3K/Akt Signaling. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2015, 66, 254–260. 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J.; Fang Y.; Han Y.; Bai X.; Yan X.; Zhang Y.; Lai R.; Zhang Z. YY-39, a tick anti-thrombosis peptide containing RGD domain. Peptides 2015, 68, 99–104. 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrieux A.; Hudry-Clergeon G.; Ryckewaert J. J.; Chapel A.; Ginsberg M. H.; Plow E. F.; Marguerie G. Amino acid sequences in fibrinogen mediating its interaction with its platelet receptor, GPIIbIIIa. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 9258–9265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y.; Huo J.-L.; Xu W.; Xiong J.; Li Y.-M.; Wu W.-T. A novel anti-platelet aggregation tripeptide from Agkistrodon acutus venom: isolation and characterization. Toxicon 2009, 54, 103–109. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H.; Zhang L.; Luo Y.; Zhang S.; Li B. Effects of collagen peptides intake on skin ageing and platelet release in chronologically aged mice revealed by cytokine array analysis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 277–288. 10.1111/jcmm.13317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni R.; Gianfranceschi G.; Koch G. On peptide de novo sequencing: a new approach. J. Pept. Sci. 2005, 11, 225–234. 10.1002/psc.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaulov A. V.; Renieri E. A.; Smolyagin A. I.; Mikhaylova I. V.; Stadnikov A. A.; Begun D. N.; Tsarouhas K.; Buha Djordjevic A.; Hartung T.; Tsatsakis A. Long-term effects of chromium on morphological and immunological parameters of Wistar rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 133, 110748. 10.1016/j.fct.2019.110748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Li Y.; Song H.; He J.; Li G.; Zheng Y.; Li B. Collagen peptides promote photoaging skin cell repair by activating the TGF-β/Smad pathway and depressing collagen degradation. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 6121–6134. 10.1039/C9FO00610A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G.; Wang F.; Zhang B.; Fan J. In vitro inhibition of platelet aggregation by peptides derived from oat (Avena sativa L.), highland barley (Hordeum vulgare Linn. var. nudum Hook. f.), and buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) proteins. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 577–586. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.; Wang B.; Li B.; Wang C.; Luo Y. Preparation and identification of peptides and their zinc complexes with antimicrobial activities from silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) protein hydrolysates. Food Res. Int. 2014, 64, 91–98. 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera J.; Lozano M. L.; Navarro-Nunez L.; Vicente V. Platelet receptors and signaling in the dynamics of thrombus formation. Haematologica 2009, 94, 700–711. 10.3324/haematol.2008.003178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganbaatar B.; Fukuda D.; Salim H. M.; Nishimoto S.; Tanaka K.; Higashikuni Y.; Hirata Y.; Yagi S.; Soeki T.; Sata M. Ticagrelor, a P2Y12 antagonist, attenuates vascular dysfunction and inhibits atherogenesis in apolipoprotein-E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 2018, 275, 124–132. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M.; Sugidachi A.; Isobe T.; Niitsu Y.; Ogawa T.; Jakubowski J. A.; Asai F. The influence of P2Y12 receptor deficiency on the platelet inhibitory activities of prasugrel in a mouse model: evidence for specific inhibition of P2Y12 receptors by prasugrel. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007, 74, 1003–1009. 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremmel T.; Yanachkov I. B.; Yanachkova M. I.; Wright G. E.; Wider J.; Undyala V. V. R.; Michelson A. D.; Frelinger A. L. III; Przyklenk K. Synergistic Inhibition of Both P2Y1 and P2Y12 Adenosine Diphosphate Receptors As Novel Approach to Rapidly Attenuate Platelet-Mediated Thrombosis. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 501–509. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa A.; Ohno K.; Jakubowski J. A.; Mizuno M.; Sugidachi A. Prasugrel reduces ischaemic infarct volume and ameliorates neurological deficits in a non-human primate model of middle cerebral artery thrombosis. Thromb. Res. 2015, 136, 1224–1230. 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khiari Z.; Rico D.; Martin-Diana A. B.; Barry-Ryan C. Structure elucidation of ACE-inhibitory and antithrombotic peptides isolated from mackerel skin gelatine hydrolysates. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 1663–1671. 10.1002/jsfa.6476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y.; Huang S.-L.; Shao Y.; Li S.; Wei J.-F. Purification and characterization of a novel antithrombotic peptide from Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 182–186. 10.1016/j.jep.2012.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.; Ye X.; Ming X.; Chen Y.; Wang Y.; Su X.; Su W.; Kong Y. A Novel Direct Factor Xa Inhibitory Peptide with AntiPlatelet Aggregation Activity from Agkistrodon acutus Venom Hydrolysates. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10846. 10.1038/srep10846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.-A.; Kim S.-H. SSGE and DEE, new peptides isolated from a soy protein hydrolysate that inhibit platelet aggregation. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 389–393. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyapina L. A.; Pastorova V. E.; Samonina G. E.; Ashmarin I. P. The effect of prolil-glycil-proline (PGP) peptide and PGP-rich substances on haemostatic parameters of rat blood. Blood Coagulation Fibrinolysis 2000, 11, 409. 10.1097/00001721-200007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X.-L.; Su W.; Wang Y.; Wang Y.-H.; Ming X.; Kong Y. The pyrrolidinoindoline alkaloid Psm2 inhibits platelet aggregation and thrombus formation by affecting PI3K/Akt signaling. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2016, 37, 1208–1217. 10.1038/aps.2016.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch N. R.; Karim Z. A.; Pineda J.; Mercado N.; Alshbool F. Z.; Khasawneh F. T. P2Y12 antibody inhibits platelet activity and protects against thrombogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 493, 1069–1074. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler-Nissen J. Determination of the degree of hydrolysis of food protein hydrolysates by trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1979, 27, 1256–1262. 10.1021/jf60226a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; Li B. Effect of molecular weight on the transepithelial transport and peptidase degradation of casein-derived peptides by using Caco-2 cell model. Food Chem. 2017, 218, 1–8. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.08.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy B. Jr.; Bhavaraju K.; Getz T.; Bynagari Y. S.; Kim S.; Kunapuli S. P. Impaired activation of platelets lacking protein kinase C-theta isoform. Blood 2009, 113, 2557–2567. 10.1182/blood-2008-07-169268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S.; Sudo T.; Niimi M.; Tao L.; Sun B.; Kambayashi J.; Watanabe H.; Luo E.; Matsuoka H. Inhibition of collagen-induced platelet aggregation by anopheline antiplatelet protein, a saliva protein from a malaria vector mosquito. Blood 2008, 111, 2007–2014. 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canobbio I.; Cipolla L.; Consonni A.; Momi S.; Guidetti G.; Oliviero B.; Falasca M.; Okigaki M.; Balduini C.; Gresele P.; Torti M. Impaired thrombin-induced platelet activation and thrombus formation in mice lacking the Ca2+-dependent tyrosine kinase Pyk2. Blood 2013, 121, 648–657. 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]