Abstract

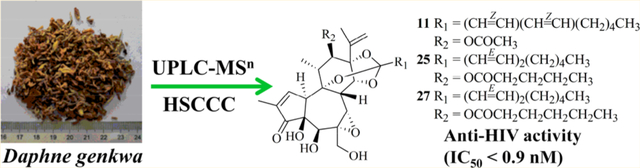

Daphnane diterpenes with a 5/7/6-tricyclic ring system exhibit potent anti-HIV activity but are found in low abundance as plant natural products. In this study, an effective approach based on mass spectrometric fragmentation pathways was conducted to specifically recognize and isolate anti-HIV compounds of this type from Daphne genkwa. Briefly, the fragmentation pathways of reference analogues were elucidated based on characteristic ion fragments of m/z 323 → 295 → 267 or m/z 253 → 238 → 197 by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-ion trap tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-IT-MSn) and then applied to the differentiations of substances with or without an oxygenated group at C-12. Twenty-seven daphnane diterpenes were successfully recognized from a petroleum ether extract of D. genkwa, including some potential new compounds and isomers that could not be identified accurately only from the ion fragments. Further separation of these target compounds using high-speed countercurrent chromatography (HSCCC) and preparative HPLC led to the isolation of three new (11, 25, and 27) and 14 known compounds, whose structures were identified and confirmed based on MS, NMR, and electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectroscopy. The isolates exhibited anti-HIV activities at nanomolar concentrations. The results demonstrated that this strategy is feasible and reliable to rapidly recognize and isolate daphnane diterpenes from D. genkwa.

Graphical Abstract

Daphnane diterpenes with a 5/7/6-tricyclic ring system that occur mainly in the family Thymelaeaceae exhibit various biological activities including anti-HIV and antitumor effects.1–3 Of significance, many of these compounds, such as huratoxin, wikstroelide A, simplexin, and wikstrotoxin A, exhibit potent anti-HIV activity at nanomolar concentrations.4 However, such compounds occur in the plant of origin at very low concentration levels.5−79 It is time-consuming and laborious to isolate them from complex mixtures using conventional repeated column chromatography.8,9 Therefore, efficient recognition and target-guided isolation are urgently required to accelerate the research on daphnane diterpenes as anti-HIV drug leads.

In recent years, HPLC-MS/MS has become a very powerful tool for the identification of active trace constituents from a complex matrix.10,11 Especially, ion-trap MS provides multi-stage MSn and generates many fragmentation ions, which is extremely suitable for the identification of target compounds. Thus far, different classes of natural compounds, such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, terpenoids, and saponins, have been analyzed and characterized by HPLC-MSn based on fragmentation pathways.12–14 However, few reports have elucidated the MS fragmentation patterns of daphnane diterpenes in detail.

Daphne genkwa Sieb. et Zucc. (Thymelaeaceae) is a traditional medicinal herb with antitumor, diuretic, and antitussive effects.15,16 Phytochemical studies of its flower buds have led to the isolation of diterpenoids, coumarins, flavonoids, lignans, and sesquiterpenoids.17–19 A preliminary experiment in the present investigation indicated that a petroleum ether extract of the flower buds of D. genkwa possessed potent anti-HIV activity (IC50 = 0.083 μg/mL). Subsequently, a strategy based on MS fragmentation pathways was used for the rapid recognition and targeted isolation of selected diterpenoids from D. genkwa via ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-ion trap tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-IT-MSn) and high-speed countercurrent chromatography (HSCCC). Altogether, 17 daphnane diterpenes, including three new compounds, were isolated and identified by using MS, NMR, and electronic circular dichroism (ECD) analysis. Also, the anti-HIV activities of nine isolated daphnane diterpenes were evaluated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Fragmentation Pathways and Recognition of Daphnane Diterpenes.

To rapidly recognize diterpenoids in a complex mixture, the fragmentation pathways of reference compounds (S1–S8) in Figures 1 and 2 were elucidated in detail based on characteristic ion fragments. Depending on the presence of an oxygenated group at C-12, these eight diterpenes could be classified into type A (S1–S4) in Figure 1 and type B (S5–S8) in Figure 2. Subtoxin A (S1) and huratoxin (S5) were taken as examples to explain the fragmentation pathways for types A and B, respectively. For subtoxin A, the MS2 fragmentation of the quasimolecular ion at m/z 643 [M + H]+ yielded three prominent fragments at m/z 583, 419, and 359, corresponding to [M − R2H + H]+, [M − R1COOH + H]+, and [M − R2H − R1COOH + H]+, respectively, as shown in Figure 1. Other fragments at m/z 625, 605, 565, 401, 341, and 323 were associated with the consecutive loss of H2O. Owing to the formation of relatively stable conjugated structures, the ion at m/z 323 had the highest abundance and its MS3 fragmentation produced the ion at m/z 295 due to decarbonylation. The MS4 fragment ion of m/z 267 came from the decarbonylation of the ion at m/z 295. Similarly, the fragmentation of S2–S4 produced mainly the fragments at m/z 359, 341, and 323 from the loss of fatty acid and H2O and at m/z 295 and 267 from the consecutive decarbonylation (Table S1, Supporting Information). For recognition of type A daphnane diterpenes, the diagnostic ions are the fragment ions at m/z 323 → m/z 295 → m/z 267.

Figure 1.

IT-MS1–4 spectra of subtoxin A (S1) and the proposed fragmentation patterns of S1-S4 reference compounds.

Figure 2.

IT-MS1–4 spectra of huratoxin (S5) and the proposed fragmentation patterns of S5-S8 reference compounds.

For huratoxin (S5), the protonated ion at m/z 585 produced fragments at m/z 567, 549, 531, 361, 343, 325, 307, 297, and 279 from the loss of fatty acid (RCOOH) and sequential dehydration and decarbonylation (Figure 2). The fragment at m/z 253 had the highest abundance and resulted from the loss of a C2H2 group from the MS2 fragment ion at m/z 279. In MS3 and MS4, fragment ions at m/z 238 and 197 originated through the loss of CH3 and C3H5, respectively, from the benzene ring. The fragmentation pathways of S6–S8 were identical to those of S5 (Table S1, Supporting Information). The fragment ions m/z 253 → m/z 238 → m/z 197 were selected as diagnostic ions for recognition of type B daphnane diterpenes.

The above diagnostic ions of types A and B were used for the rapid recognition of daphnane diterpenes with similar structures from the petroleum ether extract of D. genkwa. As a result, 27 peaks (Figure 3) were determined as daphnane diterpenes, including 25 peaks for type A and 2 peaks for type B (Table S2, Supporting Information). Among them, there were five groups of isomers, namely, peaks 7–10, peaks 11, 12, and 14, peaks 17–19, and 21, peaks 20 and 22, and peaks 23 and 24. Each group of isomers had the same fragment ions in MS1–4, which were difficult to accurately identify simply by the fragmentation ions. Peak 25, [M + H]+ at m/z 643, produced fragment ions at m/z 527, 461, and 359 in MS2 corresponding to the loss of R2H (102 Da), R1COOH (168 Da), and R2H + R1COOH (270 Da), respectively, which generated characteristic ion fragments at m/z 323, 295, and 267 (Figure S3, Supporting Information). The molecular mass of the R2 group was 14 Da greater than that (C3H7COO) of yuanhualine,20 while the R1 groups have the same molecular mass. Thus, the R2 group was deduced as C4H9COO. Similarly, the R2 group of peak 27 was deduced as C5H11COO (Figure S4, Supporting Information). Peaks 25 and 27 with the above structure units have not been reported before and were deduced as potential new diterpenes. Accordingly, it was necessary to obtain the isomers and new analogues to determine their structures and evaluate their anti-HIV activities.

Figure 3.

UPLC-IT-MSn total ion current in the positive-ion mode (A) and UPLC-UV at 233 nm (B) of the petroleum ether extract of D. genkwa.

Structure Elucidation of Isolated Daphnane Diterpenes.

Seventeen diterpenes were isolated using HSCCC, a liquid-liquid partition chromatography with high selectivity,21–23 and further purified by preparative HPLC, including three new compounds (11, 25, and 27) and 14 known compounds [yuanhuafine (1),24 yuanhuaoate C (2),25 genkwaphnine (4),26 yuanhuaoate E (6),27 yuanhuagine (10),28 isoyuanhuadine (12),29 yuanhuadine (14),28 excoecariatoxin (15),30 yuanhuahine (16),18 genkwadane D (20),31 yuanhuajine (21),28 yuanhualine (22),20 isoyuanhuacine (23),32 and yuanhuacine (24)28].

Compound 11 (yuanhuamine A), a white amorphous powder, showed 12 degrees of unsaturation based on the molecular formula (C32H42O10), which was determined by the HRESIMS ion at m/z 587.2846 [M + H]+ (calcd for C32H42O10, 587.2851). In the IR spectrum, the absorption of 1701, 1734, and 3387 cm−1 revealed the presence of hydroxy and carbonyl groups, respectively. The UPLC-MSn fragments (m/z 323, 295, and 267) indicated compound 11 is a daphnane diterpene (Figure S2, Supporting Information). The 1H NMR spectrum revealed two AB system protons at δH 3.78 (1H, d, J = 12.4, H-20a) and 3.97 (1H, d, J = 12.4, H-20b), two olefinic protons at δH 4.99 (1H, s, H-16) and 5.03 (1H, s, H-16), and five methyl groups at δH 0.88 (3H, t, H-10′), 1.99 (3H, s, H-2″), 1.84 (3H, s, H-17), 1.31 (3H, d, J = 7.2, H-18), and 1.79 (3H, s, H-19) in Table 1. The 13C NMR spectrum indicated the presence of an ester group [169.8 (C-1″)], an epoxy group [δC 60.5 (C-6) and 64.5 (C-7)], an α,β-unsaturated cyclopentanone [δC 209.7 (C-3) and 160.8 (C-1)], and an orthoester group [117.6 (C-1′)]. All the NMR signals were typical for a daphnane diterpene.28 In the HMBC spectrum, the correlated peaks (H-7/C-8, H-17/C-16, H-17/C-13, H-18/C-12, H-5/C-6, H-5/C-20, and H-14/C-1′) confirmed 11 was a daphnane diterpene (Figure 4). The similarity of the NMR signals of 11 to those of yuanhuadine (14), except for the conjugated diene signals (H-2′ to H-5′), suggested that the two compounds are geometric isomers. Based on the coupling constant (J) in the 1H NMR spectrum, 11 contains a cis,cis-conjugated diene, while 14 contains a trans,trans-conjugated diene unit. The correlations (H-2′ to H-10′) in the 1H-1H COSY spectrum indicated that the R2 group is a straight chain. Its location at C-14 was supported by the HMBC correlation between H-14/C-1′. In the NOESY spectrum, the correlation between H-18/H-12 revealed H-11 and H-12 to have a trans-orientation. The correlations of H-8/H-11, H-8/H-14, and H-7/H-14 suggested β-orientations for these protons, while the correlation between H-5/H-10 indicated α-orientations for H-5 and H-10.

Table 1.

1H (600 MHz) and 13C NMR (150 MHz) Spectroscopic Data of Compounds 11, 25, and 27 in CDCl3

| 11 | 25 | 27 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| position | <δc | <δH (J in Hz) | δc | δH (J in Hz) | δc | δH (J in Hz) |

| 1 | 160.8 | 7.57, s | 160.7 | 7.57, s | 160.6 | 7.60, s |

| 2 | 137 | 137 | 137 | |||

| 3 | 209.7 | 209.7 | 209.7 | |||

| 4 | 72.4 | 72.3 | 72.3 | |||

| 5 | 72.2 | 4.26, s | 72.2 | 4.25, s | 72.2 | 4.27, s |

| 6 | 60.5 | 60.6 | 60.6 | |||

| 7 | 64.5 | 3.59, s | 64.4 | 3.55, s | 64.4 | 3.51, s |

| 8 | 35.6 | 3.51, d (2.5) | 35.7 | 3.47, d (2.5) | 35.6 | 3.47, d (2.6) |

| 9 | 78.3 | 78.1 | 78.2 | |||

| 10 | 47.6 | 3.84, s | 47.6 | 3.82, m | 47.6 | 3.84, m |

| 11 | 44.1 | 2.37, m | 44.3 | 2.37, m | 44.2 | 2.37, m |

| 12 | 78.4 | 4.98, s | 78.3 | 5.00, s | 78.3 | 5.00, s |

| 13 | 83.9 | 83.9 | 83.9 | |||

| 14 | 80.2 | 4.83, d (2.5) | 80.5 | 4.76, d (2.5) | 80.5 | 4.78, d (2.5) |

| 15 | 143.1 | 143.1 | 143.2 | |||

| 16 | 113.5 | 4.99, s; 5.03, s | 113.5 | 4.98, s; 4.95, s | 113.5 | 4.98, s; 4.95, s |

| 17 | 18.7 | 1.84, s | 18.8 | 1.8, s | 18.8 | 1.83, s |

| 18 | 18.5 | 1.31, d (7.2) | 18.4 | 1.37, d (7.2) | 18.4 | 1.33, d (7.2) |

| 19 | 10 | 1.79, s | 10 | 1.79, s | 10 | 1.79, s |

| 20 | 65.4 | 3.78, d (12.4) | 65.2 | 3.79, d (12.6) | 65.2 | 3.81, d (12.5) |

| 3.97, d (12.4) | 3.94, d (12.5) | 3.95, d (12.5) | ||||

| 1′ | 117.6 | 117.1 | 117.1 | |||

| 2′ | 120.2 | 5.44, d (11.3) | 122.4 | 5.63, d (15.4) | 122.4 | 5.65, d (15.5) |

| 3′ | 136.2 | 6.23, dd (15.6, 11.3) | 135.2 | 6.65, dd (15.4, 10.7) | 135.2 | 6.68, dd (15.4, 10.7) |

| 4′ | 126.7 | 6.86, dd (15.0, 11.8) | 128.7 | 6.04, dd (15.2, 10.7) | 128.7 | 6.06, dd (15.1, 10.7) |

| 5′ | 140.2 | 5.82, m | 139.5 | 5.85, m | 139.5 | 5.87, m |

| 6′ | 32.8 | 2.10, m | 32.8 | 2.06, m | 32.8 | 2.10, m |

| 7′ | 28.5 | 1.40, m | 28.9 | 1.41, m | 28.9 | 1.40, m |

| 8′ | 31.6 | 1.27, m | 31.5 | 1.26, m | 31.4 | 1.26, m |

| 9′ | 22.6 | 1.26, m | 22.6 | 1.27, m | 22.6 | 1.27, m |

| 10′ | 14.2 | 0.88, t | 14.2 | 0.88, t | 14.2 | 0.88, t |

| 1″ | 169.8 | 172 | 172.7 | |||

| 2″ | 21.3 | 1.99, s | 36.1 | 2.22, m | 34.5 | 2.25, m |

| 3″ | 27.4 | 1.65 m | 24.6 | 1.65, m | ||

| 4″ | 22.5 | 1.27, m | 27.4 | 1.27, m | ||

| 5″ | 14.3 | 0.98, t | 22.5 | 1.26, m | ||

| 6″ | 14 | 0.98, t | ||||

Figure 4.

Key 1H-1H COSY, HMBC, and NOESY correlations of 11.

Compound 25 (yuanhuamine B) was obtained as a white amorphous powder. Its HRESIMS ion at m/z 629.3315 [M + H]+ (calcd for C35H48O10, 629.3320) indicated 12 degrees of hydrogen deficiency. The IR spectrum indicated the presence of hydroxy (3425 cm−1) and carbonyl (1708 and 1752 cm−1) moieties. The NMR data indicated one more methylene [22.5 (C-4″)] in 25 compared with 22.30 In the 1H-1H COSY spectrum of 25, the correlations between H-2″, H-3″, H-4″, and H-5″ indicated the presence of an n-butyl fragment (Figure S5, Supporting Information), which was consistent with the results from UPLC-MSn. Furthermore, a C4H9COO group was assigned at C-12 based on the correlations between H-12/C-1″ and H-2″/C-1″ in the HMBC spectrum. In the NOESY spectrum, correlations were observed between H-12/H-18, H-8/H-11, H-8/H-14, H-7/H-14, and H-5/H-10, which were analogous to those for 11.

The molecular formula of compound 27 (yuanhuamine C), obtained as an amorphous powder, was assigned as C36H50O10 according to its HRESIMS ([M + H]+ at m/z 643.3471, calcd for C36H50O10), with 12 degrees of hydrogen deficiency. The IR spectrum revealed the presence of hydroxy (3491 cm−1) and carbonyl (1749 and 1711 cm−1) groups. Based on the 1H and 13C NMR spectra, compounds 27 and 25 have the same skeleton and differ only in the C-12 side chain. In the 1H-1H COSY spectrum (Figure S6, Supporting Information), the correlations between H-2″, H-3″, H-4″, H-5″, and H-6″ proved the presence of an n-pentyl chain in 27. Accordingly, the presence of a C5H11COO group at C-12 was confirmed by the HMBC correlations between H-12/C-1″ and H-2″/C-1″.The correlations between H-12/H-18, H-8/H-11, H-8/H-14, H-7/H-14, and H-5/H-10 in the NOESY spectrum were consistent with those of 11.

To determine the absolute configuration of compounds 11, 25, and 27, their experimental ECD data were obtained. All three compounds showed the same Cotton effect (Figure 5A). The calculated ECD spectra of (4S,5R,6S,7S,8S,9R,−10S,11R,12R,13S,14R)-25 and (4R,5S,6R,7R,8R,9S,−10R,11S,12S,13R,14S)-25 were obtained from the B3LYP/6–311+G(d,p) (Figure 5B), and the former was consistent with the experimental ECD curve of 25. Therefore, the structure and absolute configuration of 25 were established.

Figure 5.

Experimental ECD spectra of 11, 25, and 27 in MeOH (A) and calculated ECD spectra of 25 (B).

Nine diterpenoids, including isomers (12 and 14), the new compounds (11, 25, and 27), the most abundant compounds (4, 16, and 24), and compound 2, were evaluated for their anti-HIV activity and cytotoxicity, with the results presented in Table 2. Most of the compounds, except 2 and 16, showed extremely potent anti-HIV activity at nanomolar concentrations. Compared with the positive control AZT (zidovudine), the diterpenoids tested were more potent with higher selectivity indexes. Structurally, the main difference between the more potent (4, 11, 12, 14, 24, 25, and 27) and the less potent (2) indicated that the orthoester group at C-9, C-13, and C-14 might be responsible for the enhanced anti-HIV activity, which is consistent with our previous study.4

Table 2.

Anti-HIV Activity and Cytotoxicity of Nine Daphnane Diterpenesa

| anti-HIV | cytotoxicity | selectivity index | |

|---|---|---|---|

| compound | IC5O (nM) | CC50 (μM) | CC50/IC50 |

| 2 | 62.9 ± 14.7 | >6.6 | >105 |

| 4 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | >6.6 | >3320 |

| 11 | <0.9 | >6.8 | >8035 |

| 12 | <0.9 | >6.8 | >8035 |

| 14 | 5.3 ± 1.8 | >6.8 | >1288 |

| 16 | 805.0 ± 164.5 | >6.7 | >8 |

| 24 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | >6.2 | >5144 |

| 25 | <0.8 | >6.4 | >7962 |

| 27 | <0.8 | >6.2 | >7987 |

| aztb | 20.0 ± 5.6 | >15.0 | >750 |

Values are mean ± SD (n = 3).

Positive control substance.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Experimental Procedures.

Optical rotations were measured using an Autopol V Plus instrument. UV and ECD spectroscopic data were obtained with a Brighttime Chirascan spectrometer. IR spectra were detected by a PE Spectrum RXI spectrophotometer. NMR data were recorded on a Bruker Ultrashield Plus 600 MHz instrument in CDCl3 with tetramethylsilane as an internal standard. HRESIMS data were acquired with an AB SCIEX Triple TOF 5600+ mass spectrometer. Isolation was performed on a TBE-300A HSCCC and preparative Agilent 1200 HPLC.

Eight daphnane diterpenoids, subtoxin A (S1), stelleralide I (S2), wikstroelide B (S3), wikstroelide J (S4), huratoxin (S5), wikstroelide A (S6), simplexin (S7), and wikstroelide M (S8), were isolated previously from Stellera chamaejasme in our laboratory, and their structures were established from MS and comprehensive NMR experiments with literature values.4 The purities of all compounds were determined to be no less than 95% by HPLC.

Plant Material.

The flower buds of D. genkwa were purchased from Tianma Medical Company (Anhui, People’s Republic of China) in June 2016 and authenticated by Prof. Daofeng Chen. A voucher specimen (DFC-ZHD-DG-2016–09) has been deposited in the Department of Pharmacognosy, School of Pharmacy, Fudan University.

UPLC-IT-MS Analyses of Daphnane Diterpenoids from D. genkwa.

Analyses were conducted using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 UPLC coupled with a Thermo LTQ Velos Pro ion trap mass spectrometer via an electrospray ionization interface. A YMC-Triart C18 column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) was applied for the separation with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min at 25 °C. A mobile phase consisted of eluent A (acetonitrile) and B (water) programmed as follows: 0–2 min, 50% A; 2–42 min, 50–90% A; 42–45 min, 90–100% A; 45–70 min, 100% A. The operating conditions were optimized as follows: positive-ion mode, auxiliary gas (N2) flow, 10 arb; sheath gas (N2) flow, 40 arb; collision gas (He); source voltage, 3.5 kV; capillary temperature, 350 °C; capillary voltage, 35 V. A data-dependent scan mode was selected for MSn analysis.

Extraction and Isolation.

Dried powders of D. genkwa flower buds (1.0 kg) were extracted with methanol. The filtrates were concentrated to obtain a crude MeOH extract (202.0 g), which was partitioned by liquid-liquid extraction with petroleum ether and water. The petroleum ether fraction (23.2 g) was repeatedly subjected to HSCCC. Petroleum ether-ethyl acetate-methanol-water 2:1:1.5:1.5, 2:1:1.8:1.2, and 2:1:2.1:0.9 (v/v/v/v) were selected for stepwise separation in the period of 0–250, 250–500, and 500–700 min, respectively, to afford fractions a-g (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Subsequently, the fractions were purified by means of preparative HPLC with a Phenomenex-Luna C18 column (250 mm × 10 mm, 5 μm) using CH3CN-H2O (3 mL/min). Fraction a (21.1 mg) was purified with a gradient elution (60% to 70% CH3CN in 20 min). Finally, 1 (2.1 mg) and 2 (2.8 mg) were obtained. Fraction b (22.8 mg) was purified by isocratic elution (75% CH3CN in 25 min) and afforded 4 (3.7 mg) and 6 (6.3 mg). Fraction c (37.5 mg) was purified using linear gradient elution (65% to 90% CH3CN in 30 min) to obtain 10 (4.4 mg), 11 (1.7 mg), and 12 (1.9 mg). Fractions d (53.6 mg) and f (33.5 mg) were purified using isocratic elution (79% CH3CN in 35 min) to yield 14 (12.0 mg) and 20 (1.7 mg), 22 (1.9 mg), 24 (16.1 mg), respectively. Fraction e (29.0 mg) was purified by linear gradient elution (75% to 95% CH3CN in 35 min) and yielded 15 (2.7 mg), 16 (3.5 mg), 21 (6.0 mg), and 23 (2.1 mg). Fraction g (31.0 mg) was purified with a linear gradient elution (80% to 95% CH3CN in 35 min) and yielded 25 (2.4 mg) and 27 (2.7 mg).

Yuanhuamine A (11): white, amorphous power; [α]25D +9.0 (c 0.10, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 235 (4.06) nm; ECD (MeOH) λmax (Δε) 228 (−10.28), 246 (−0.86), 253 (−1.84) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3387, 1734, 1701, 1377, 1227 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 587.2846 [M + H]+ (calcd for C32H42O10, 587.2851).

Yuanhuamine B (25): white, amorphous power; [α]25D +13.0 (c 0.10, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 234 (3.61) nm; ECD (MeOH) λmax (Δε) 227 (−12.53), 246 (+2.90), 259 (−0.46) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3425, 1752, 1708 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 629.3315 [M + H]+ (calcd for C35H48O10, 629.3320).

Yuanhuamine C (27): white, amorphous power; [α]25D +14.0 (c 0.10, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 233 (3.62) nm; ECD (MeOH) λmax (Δε) 226 (−8.63), 246 (+1.43), 261 (−0.78) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3491, 1749, 1711 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 643.3471 [M + H]+ (calcd for C36H50O10, 643.3477).

Anti-HIV and Cytotoxicity Assays.

Compounds were evaluated by anti-HIV and cytotoxicity assays according to published procedures.33

Supplementary Material

Chart 1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81273486), the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (2012007113011), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA (AI033066) to K.-H.L.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00993.

UPLC-IT-MSn data of reference and 27 daphnane diterpenes, HSCCC chromatogram of isolation process, and UPLC-IT-MSn, IR, and NMR spectra of 11, 25, and 27 (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Yoshida M; Feng WJ; Saijo N; Ikekawa T Int. J. Cancer 1996, 66, 268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Asada Y; Sukemori A; Watanabe T; Malla KJ; Yoshikawa T; Li W; Koike K; Chen CH; Akiyama T; Qian KD; Nakgawa-Goto K; Morris-Natschke SL; Lee KH Org. Lett 2011, 13, 2904–2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).He W; Cik M; Van Puyvelde L; Van Dun J; Appendino G; Lesage A; Van der Lindin I; Leysen JE; Wouters W; Mathenge SG; Mudida FP; De Kimpe N Bioorg. Med. Chem 2002, 10, 3245–3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Yan M; Lu Y; Chen CH; Zhao Y; Lee KH; Chen DF J. Nat. Prod 2015, 78, 2712–2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wang Z; Qu Y; Li Wang; Zhang X; Xiao H J. Sep. Sci 2016, 39, 1379–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chow S; Fletcher MT; Mckenzie RA J. Agric. Food Chem 2010, 58, 7482–7487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Huang SZ; Zhang XJ; Li XY; Kong LM; Jiang HZ; Ma QY; Liu YQ; Hu JM; Zheng YT; Li Y; Zhou J; Zhao YX Phytochemistry 2012, 75, 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hayes PY; Chow S; Somerville MJ; Fletcher MT; De Voss JJ J. Nat. Prod 2010, 73, 1907–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Jolad SD; Hoffmann J; Timmermann BN; Schram KH; Cole JR; Bates RB; Klenck RE; Tempesta MS J. Nat. Prod 1983, 46, 675–680. [Google Scholar]

- (10).de Souza Figueiredo F; Celano R; de Sousa Silva D; das Neves Costa F; Hewitson P; Ignatova S; Piccinelli AL; Rastrelli L; Leitao SG; Leitao GG J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1481, 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Spolnik G; Wach P; Rudzinski KJ; Skotak K; Danikiewicz W; Szmigielski R Anal. Chem 2018, 90, 3416–3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zhang JY; Zhang Q; Li N; Wang ZJ; Lu JQ; Qiao YJ Talanta 2013, 104, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Qi HW; Feng F; Zhai JF; Chen FM; Liu T; Zhang FF; Zhang F Talanta 2019, 191, 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Vaclavik L; Krynitsky AJ; Rader JI Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 810, 45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Han BS; Kim KS; Kim YJ; Jung HY; Kang YM; Lee KS; Sohn MJ; Kim CH; Kim KS; Kim WG J. Nat. Prod 2016, 79, 1604–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Park BY; Min BS; Oh SR; Kim JH; Bae KH; Lee HK Phytother. Res 2010, 20, 610–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Jiang CP; He X; Yang XL; Zhang SL; Li H; Song ZJ; Zhang CF; Yang ZL; Li P; Wang CZ; Yuan CS Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 830–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hong JY; Nam JW; Seo EK; Lee SK Chem. Pharm. Bull 2010, 41, 234–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Okunishi T; Umezawa T; Shimada M J. Wood Sci. 2001, 47, 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hong JY; Nam JW; Seo EK; Lee SK Chem. Pharm. Bull 2010, 58, 234–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ito Y J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1065, 145–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Han C; Wang SS; Li ZR; Chen C; Hou JQ; Xu DQ; Wang RZ; Lin YL; Luo JG; Kong LY Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1016, 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Shi SY; Ma YJ; Zhang YP; Liu LL; Liu Q; Peng MJ; Xiong X Sep. Purif. Technol 2012, 89, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Wang CR; Huang HZ; Xu RS; Dou YY; Wu XC; Li Y; Ouyang SH Acta Chim. Sin 1982, 40, 835–839. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zeng YM; Zuo WJ; Sun MG; Meng H; Wang QH; Wang JH; Li X Helv. Chim. Acta 2009, 92, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kasal R; Lee KH; Huang HC Phytochemistry 1981, 20, 2592–2594. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ohigashi H; Hirota M; Ohtsuka T; Koshimizu K; Fujiki H; Suganuma M; Yamaizumi Z; Sugimura T Agric. Biol. Chem 1982, 46, 2605–2608. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Zhang SX; Li XN; Zhang FH; Yang PW; Gao XJ; Song QL Bioorg. Med. Chem 2006, 14, 3888–3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Xia SX; Li LZ; Li FF; Yang Y; Song SJ; Gao PY; Tang S Acta Chim. Sin 2011, 69, 2518–2522. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Powell RG; Weisleder D; Smith CR Jr. J. Nat. Prod 1985, 48, 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Li FF; Sun Q; Hong LL; Li LZ; Wu YY; Xia MY; Ikejima T; Peng Y; Song SJ Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2013, 23, 2500–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Shao ZY; Shang Q; Zhao NX; Zhang SJ; Xia GP; Bai XX; Dong HL; Han YM Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2013, 44, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Dang Z; Zhu L; Lai W; Bogerd H; Lee K-H; Huang L; Chen C-H ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2016, 7, 240–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.