Abstract

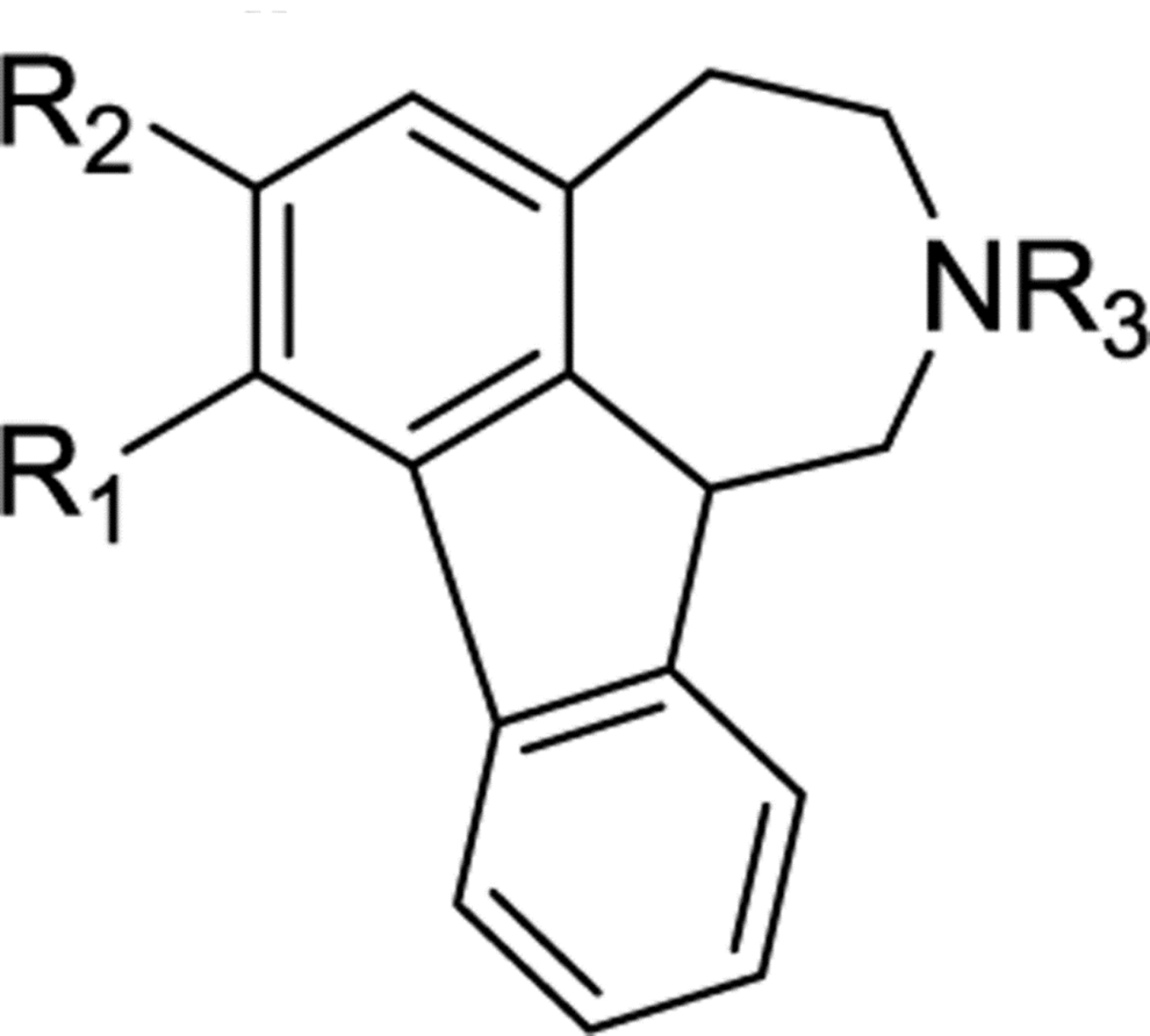

The novel 1,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine framework, a structurally rigidified variant of the 1-phenylbenzazepine template, was synthesized via direct arylation as a key reaction. Evaluation of the binding affinities of the rigidified compounds across a battery of serotonin, dopamine and adrenergic receptors indicates that this scaffold unexpectedly has minimal affinity for D1 and other dopamine receptors and is selective for the 5-HT6 receptor. The affinity of these systems at the 5-HT6 receptor is significantly influenced by electronic and hydrophobic interactions as well as the enhanced rigidity of the ligands. Molecular docking studies indicate that the reduced D1 receptor affinity of the rigidified compounds may be due in part to weaker H-bonding interactions between the oxygenated moieties on the compounds and specific receptor residues. Key receptor-ligand H-bonding interactions, salt bridges and π-π interactions appear to be responsible for the 5-HT6 receptor affinity of the compounds. Compounds 10 (6,7-dimethoxy-2,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine) and 12 (6,7-dimethoxy-2-methyl-2,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine ) have been identified as structurally novel, high affinity (Ki = 5 nM), selective 5-HT6 receptor ligands.

Keywords: 5-HT6, D1, dopamine receptor, serotonin receptor, benzazepine, docking

Graphical Abstract

Rigidification of the D1 receptor selective 1-phenylbenzaazewpine scaffold diminishes affinity for D1 and other dopamine receptors and affords novel 1,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepines with high affinity and selectivity for the 5-HT6 receptor. Docking studies reveal important H-bonding, salt bridge and pi-pi interactions that contribute to the 5-HT6 receptor affinity of the rigidified compounds.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dopamine receptors are classified within the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily and are associated with neuropsychiatric disorders. There are two families of dopamine receptor – D1-like receptors comprising D1 and D5 receptors and D2-like receptors comprising D2, D3 and D4 receptors. D1-like receptors are implicated in a range of physiological effects such as locomotion, cognition and addictive behaviors (Ashby, Valentin, & von Meer, 2015; Bell, 1987; Caruana, Heber, Brigden, & Raftery, 1987; Eilam, Clements, & Szechtman, 1991; Nieoullon & Coquerel, 2003; Robbins, 2003; Schwartz, 1984). As such, D1 receptors have been targeted in the evaluation of potential treatments for Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia and drug abuse (Asin, Domino, Nikkel, & Shiosaki, 1997; Mu et al., 2007; Mutschler & Bergman, 2002; Rascol et al., 1999).

The 1-phenylbenzazepine scaffold is known to display selective affinity for D1-like receptors (i.e. versus D2-like receptors as well as other CNS receptors). A number of 1-phenylbenzazepines are commercially available (Figure 1) and are commonly used as pharmacological tool compounds. On the basis of prior structure-affinity relationship (SAR) studies, the catechol moiety present in these compounds is important for strong D1 receptor affinity and agonist activity. The conformation of the pendant phenyl ring of 1-phenylbenzazepines appears to have some significance for D1 receptor affinity. Conformational restriction of prototypical benzazepine SKF 38393 via connecting the 1-phenyl ring to the azepine moiety via an ethylene bridge, resulted in a decrease in D1 receptor affinity, with the trans-isomer having 85-fold higher D1 receptor affinity than the corresponding cis-isomer (Clark, McCorvy, Watts, & Nichols, 2011). Similar tethering via oxy-methylene or thio-methylene functionalities had mixed results – a slightly decrease in D1 receptor affinity in the case of the oxy-methylene bridged compound and a slight increase in D1 receptor affinity for the thio-methylene bridged compound (Clark et al., 2011). Conformational restriction of the 1-phenyl ring of SKF 38393 by tethering to the catechol ring via a methylene or ethylene bridge results in an approximately 50-fold and 30-fold decrease in D1 receptor affinity respectively (Snyder et al., 1995).

Figure 1.

Structures of some commercially available 1-phenylbenzazepine D1 receptor ligands

Previous structure-affinity and computational studies indicate that coplanarity or near coplanarity of aryl rings in 1-phenylbenzazepines and related scaffolds is important for D1-like receptor affinity.(Berger et al., 1989; Ladd et al., 1986) However previously synthesized compounds do not have the aryl rings locked into a coplanar conformation. We considered an alternative mode of rigidification (Fig. 2) of the benzazepine scaffold in which both aryl rings are directly connected, and were curious to find out the extent to which such molecules would retain affinity and selectivity for the D1 receptor. Such molecules would force coplanarity of the aryl rings. We contemplated that their binding affinity evaluation would shed light on the tolerance for coplanarity of the aryl rings for D1 receptor affinity of 1-phenylbenzazepines and could potentially afford compounds with improved D1 receptor affinity and/or selectivity versus other CNS receptors. Thus, we decided to synthesize rigidified 1-phenylbenzazepines in which the two phenyl rings are directly connected via an aryl-aryl bond and to evaluate the compounds for affinity across major CNS receptor families comprising dopamine, serotonin and adrenergic receptors. We report herein the synthesis of the novel 1,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine framework and present data on the receptor binding evaluations and serendipitous discovery of 5-HT6 receptor affinity as well as our receptor docking studies on the scaffold.

Figure 2.

Structure of rigidified benzazepines in previous studies versus this study

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis

We envisaged that the desired rigidified template could be obtained via direct arylation of C2’-brominated 1-phenyl benzazepine intermediates that are readily available. This direct biaryl cyclization approach has been used by us in the synthesis of structurally similar aporphine, homoaporphine and azafluoranthene frameworks (Chaudhary & Harding, 2011; Chaudhary, Pecic, Legendre, & Harding, 2009; Ponnala & Harding, 2013).

The brominated 1-phenylbenzazepine substrates were prepared as depicted in Scheme 1. Commercially available phenethylamine 4 was reacted with epoxide 5 to give the amino alcohol 6. Alcohol 6 was cyclized under acidic conditions to afford the benzazepine 7. Compound 7 was subsequently N-boc protected to afford the biaryl cyclization precursor 8.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and Conditions: (a) LiNF2, THF, reflux, 24h, 56%; (b) 1.TFA, H2SO4 (18M), rt, 5h; 2. NaOAc, 43%; (c) Boc2O, TEA, ACN, rt, 18h, 36%; (d) Pd(OAc)3, (t-Bu)2PMeHBF4, Pivalic Acid, K2CO3, DMSO, 120 °C, 2h, 86%; (e) TFA, DCM, rt, 2h, 52%; (f) BBr3, DCM, 0 °C, 18h, 46–54%; (g) HCHO, ACN, rt, 18h, 78%.

Table 1 summarizes our efforts at optimizing the biaryl cyclization of 8 to 9. We began by investigating microwave conditions for this reaction that had proved successful in previous microwave-assisted aporphine and homoaporphine syntheses (Chaudhary & Harding, 2011; Chaudhary et al., 2009). As shown in entries 1–3, the microwave conditions using ligands A, B or C were unsuccessful.

Table 1.

Optimization of direct arylation conditions

| Entry | Basea | Solvent | Ligandb | Pivalic Acid | Temp (°C) | Time | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | K2CO3 | DMSO | A | - | 135 (μw) | 5 min | - |

| 2 | K2CO3 | DMSO | B | - | 135 (μw) | 5 min | - |

| 3 | K2CO3 | DMSO | C | - | 135 (μw) | 5 min | - |

| 4 | K2CO3 | DMSO | A | 0.4 equiv | 135 (μw) | 5 min | - |

| 5 | K2CO3 | DMSO | B | 0.4 equiv | 135 (μw) | 5 min | - |

| 6 | K2CO3 | DMSO | C | 0.4 equiv | 135 (μw) | 5 min | <5c |

| 7 | K2CO3 | DMSO | C | 0.4 equiv | 120 | 18 h | - |

| 8 | K2CO3 | DMF | C | 0.4 equiv | 120 | 18 h | - |

| 9 | Cs2CO3 | DMF | C | 0.4 equiv | 120 | 18 h | - |

| 10 | Na2CO3 | DMF | C | 0.4 equiv | 120 | 18 h | - |

| 11 | K2CO3 | DMSO | C | 0.4 equiv | 120 | 8 h | - |

| 12 | K2CO3 | DMSO | C | 0.4 equiv | 120 | 6 h | 36 |

| 13 | K2CO3 | DMSO | C | 0.4 equiv | 120 | 2 h | 86 |

3 equiv. used;

0.2 equiv. used;

estimated via 1H-NMR of semi-purified mixture

Although no substrate remained, the reaction led to an intractable mixture of products (based on TLC), apparently from significant decomposition. The use of pivalic acid has been shown to enhance product formation in some direct arylation reactions.(Lafrance & Fagnou, 2006) The conditions in entries 1–3 were repeated with the addition of pivalic acid; these conditions were again largely unsuccessful (entries 4–6). However, some product was obtained (albeit a very low yield) when ligand C was used (entry 6).

Given the apparent product decomposition under microwave conditions, we next investigated milder thermal conditions. Ligand C was used for these reactions since use of this ligand had given some product with microwave conditions. As entries 7–11 show, no product was obtained when either DMF or DMSO was used as solvent, when Cs2CO3 or Na2CO3 were used instead of K2CO3 or when the reaction was heated at 120 °C for over 8 hours. When the reaction time was lowered to 6 hours however, a moderate yield of product was obtained (36%, entry 12). Recognizing the time sensitivity of the reaction, the yield was significantly improved when the reaction time was lowered to 2 hours.

The cyclized product 9 was then treated with TFA to effect N-Boc deprotection (Scheme 1), producing compound 10. The methoxy groups in 10 were deprotected with BBr3 to afford catechol 11. Methylation of 10 via reductive amination gave compound 12 which was subsequently treated with BBr3 to give catechol 13.

Receptor binding studies

Rigidified benzazepines 10 - 13 prepared as described above were evaluated for affinity at dopamine receptors and at a subset of serotonin and α-adrenergic receptors in order to gauge the broader receptor selectivity of the rigidified scaffold. Data for the dopamine, serotonin and adrenergic receptor evaluations are presented in Tables 2a, 2b and 2c respectively.

Table 2a.

Affinity of analogs at dopamine receptors

| Ki (nM)a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd # | R1 | R2 | R3 | D1b | D2c | D3c | D4c | D5b |

| 10 | OMe | OMe | H | NAd | 780 | 415 | NA | NA |

| 11 | OH | OH | H | 8820 | N/A | 2924 | NA | NA |

| 12 | OMe | OMe | Me | 2462 | 636 | 79 | NA | NA |

| 13 | OH | OH | Me | 865 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| (+)-butaclamol | 2.03 | |||||||

| haloperidol | 10.75 | |||||||

| nemonapride | 0.14 | 0.78 | ||||||

| SKF83566 | 7.99 | |||||||

Experiments conducted in triplicate; SEM values are within 15% of reported values;

[3H]-SCH23390 used as radioligand;

[3H]N-methylspiperone used as radioligand;

NA- not active- ligands displayed <10% inhibition in a primary assay at a ligand concentration of 10 μM

Table 2b.

Affinity of analogs at serotonin receptors

| Ki (nM)a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd # | R1 | R2 | R3 | 5-HT1Ab | 5-HT1Bc | 5-HT2Ad | 5-HT5Ae | 5-HT6e |

| 10 | OMe | OMe | H | 110 | 255 | 1680 | 578 | 5 |

| 11 | OH | OH | H | 151 | 451 | 1564 | 244 | 38 |

| 12 | OMe | OMe | Me | NAf | NA | 811 | 286 | 5 |

| 13 | OH | OH | Me | 393 | 1032 | 352 | 363 | 123 |

| 8-OH-DPAT | 0.81 | |||||||

| ergotamine | 9.28 | 6.92 | ||||||

| clozapine | 3.91 | 3.88 | ||||||

Experiments conducted in triplicate; SEM values are within 15% of reported values;

[3H]-WAY100635 used as radioligand;

[3H]GR125743 used as radioligand;

.[3H]ketanserin used as radioligand;

[3H]LSD used as radioligand;

NA- not active- ligands displayed <10% inhibition in a primary assay at a ligand concentration of 10 μM

Table 2c.

Affinity of analogs at α-adrenergic receptors

| Ki (nM)a. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd # | R1 | R2 | R3 | α1Ab | α1Bb | α2Ac | α2Bc | α2Cc |

| 10 | OMe | OMe | H | 545 | 2592 | 1603 | 1120 | 774 |

| 11 | OH | OH | H | 3197 | NAd | 2590 | 2197 | 1106 |

| 12 | OMe | OMe | Me | 2863 | 5874 | 1174 | NA | 472 |

| 13 | OH | OH | Me | >10,000 | NA | NA | 5822 | 1959 |

| prazosin | 0.38 | 0.39 | ||||||

| oxymetazoline | 9.30 | 65.58 | ||||||

| yohimbine | 10.85 | |||||||

Experiments conducted in triplicate; SEM values are within 15% of reported values;

[3H]Prazosin used as radioligand;

[3H]Rauwolscine used as radioligand;

NA- not active- ligands displayed <10% inhibition in a primary assay at a ligand concentration of 10 μM

Somewhat unexpectedly, compounds 10 - 13 generally lacked any significant affinity for dopamine receptors (Table 2a) – there was no affinity for D4 and D5 receptors. The highest affinity at any dopamine receptor was seen by compound 12 at the D3 receptor (79 nM). Some affinity was observed at the D1 receptor for compounds 11-13, but this affinity was generally quite low (865 – 8820 nM). Thus, it is apparent that rigidification of the 1-phenylbenzazepine scaffold into the 1,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine framework negatively impacts dopamine D1 receptor affinity.

Table 2b shows data from evaluation of the receptor binding of the compounds at a subset of serotonin receptors – 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2A, 5-HT5A and 5-HT6. Generally, the compounds displayed higher affinity for serotonin receptors than for dopamine receptors. Interestingly, while affinity for 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2A and 5-HT5A receptors was low to moderate, the affinity of the group of compounds at the 5-HT6 receptor was higher. That is, all four compounds were selective for the 5-HT6 receptor among the group of 5-HT receptors evaluated. Compounds 10 and 12 were the most potent 5-HT6 receptor binders identified (Ki = 5 nM for both compounds). These compounds had stronger 5-HT6 receptor affinity than their catecholic counterparts (11 and 13 respectively), indicating that the pharmacokinetically problematic catechol moiety (Wu et al., 2005) is not required for high 5-HT6 receptor affinity of the scaffold.

Data for evaluation at α−adrenergic receptors – α1A, α1B, α2A, α2B and α2C are presented in Table 2c. The compounds displayed low to moderate affinity at all adrenergic receptors evaluated. Overall, the receptor binding studies indicate that rigidification of the 1-phenylbenzazepine scaffold into a 1,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine framework is not beneficial for D1 receptor binding; on the other hand, the scaffold seems to have a significant preference for 5-HT6 receptors.

Docking studies

In order to rationalize the unexpected lack of D1 receptor affinity of the rigidified benzazepines, as well as the serendipitous discovery of their high 5-HT6 receptor binding and selectivity, a series of computational docking studies at D1 and 5-HT6 receptors was performed to prepared homology models of these dopamine and serotonin receptors. In this context, we investigated the docked ligand poses and identified key receptor-ligand interactions that influence binding to the receptors and provide a deeper appreciation of the observed SAR differences towards D1 and 5-HT6 receptor systems.

D1 receptor outcomes

A homology model of the D1 receptor target system was constructed from the high-resolution crystal structure of the human β2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor with pdb code 2RH1 (Cherezov et al., 2007) followed by induced fit docking with several 1-phenylbenzazepine analogs to generate a D1 receptor structure with appropriate amino acid backbone and side-chain orientations within the ligand binding site. This process utilized the Prime Structure Prediction and Glide software modules from Schrödinger (2019) as well as significant manual intervention to confirm the formation of known important receptor-ligand interactions, particularly the protonated nitrogen – aspartate salt bridge. The docking simulations were conducted using Schrödinger’s Glide software in Standard Precision (SP) mode (Halgren et al., 2004) and comprised the conformationally rigid set of ligands, 10 - 13, as well as the conformationally mobile SKF 38393, with an unfused pendant 1-phenyl ring. The Glidescore scoring function was utilized to predict the ligand binding energy and the value for the highest ranked pose of each ligand within the D1 target receptor is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Predicted binding ebergies from Glidescore for ligands SKF 38393 and 10 - 13 at the D1 and 5-HT6 receptors

| Binding energies (kcal/mol) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cmpd # | D1 | 5-HT6 |

| SKF 38393 | −9.6 | −8.5 |

| 10 | −8.2 | −9.3 |

| 11 | −8.7 | −9.4 |

| 12 | −8.0 | −9.1 |

| 13 | −8.4 | −9.0 |

A depiction of the docked poses for compound 10 and compound 12 in the D1 receptor binding site is illustrated in Figure 3. These compounds have similar structures with an extra methyl group on the protonated nitrogen for 12. In this context, they also form the same docked pose within the D1 receptor binding site with similar predicted binding energies (−8.2 kcal/mol and −8.0 kcal/mol for compounds 10 and 12, respectively). The main receptor-ligand interactions, comprise the protonated secondary N-Asp103 salt bridge and π-π hydrophobic interactions involving the rigidified 1-phenylbenzazepine aromatic rings with Phe288 and Phe313. The other rigidified systems, compounds 11 and 13, gave rise to slightly better binding energies toward the D1 receptor (−8.7 kcal/mol and −8.4 kcal/mol, respectively) due to the replacement of the catechol methoxy moieties with hydroxyl groups, which form H-bonds with the receptor Ser198 and Ser202 residues. The conformationally mobile ligand SKF 38393 showed the highest predicted binding energy towards the D1 receptor (−9.6 kcal/mol) as it forms slightly stronger receptor-ligand interactions (protonated N-Asp103 salt bridge, H-bonds to Ser198 and Ser202 and π-π hydrophobic interactions) due to its increased flexibility.

Figure 3.

Docked poses of compounds 10 (green carbon atoms) and 12 (pink carbon atoms) in the D1 receptor target (grey carbon atoms, colored helices and loops). Key hydrogen bonding interactions are depicted by the yellow dashed lines, salt bridges by the pink dashed lines and aromatic hydrogen bonds by the blue dashed lines.

5-HT6 receptor outcomes

A homology model of the serotonin 5-HT6 receptor system was developed from the high-resolution crystal structure of the human 5-HT2B receptor with pdb code 4IB4 (Wang et al., 2013) by aligning highly conserved residues (Gonzalez-Vera et al., 2017) followed by induced fit docking with several phenylbenzazepine analogs and related locked systems. This approach produced a 5-HT6 receptor structure with suitable amino acid residue orientations in the ligand binding pocket. The Glidescore estimates of the binding energy for the highest ranked pose of each ligand within the 5-HT6 target receptor are also shown in Table 3.

The conformationally rigid compounds 10 – 13 all gave similar docked poses and binding energies towards the 5-HT6 receptor. For example, the outcome of the docking simulations for compound 10 and compound 12 in the 5-HT6 binding site is depicted in Figure 4. They yielded binding energies of −9.3 kcal/mol and −9.0 kcal/mol, respectively and generated the same docked pose with analogous key receptor-ligand interactions, including the protonated secondary N-Asp106 salt bridge, π-π hydrophobic interactions involving the 1-phenylbenzazepine aromatic rings with Phe284, Phe285 and Phe302 and some aromatic H-bonds. Compound SKF 38393 gave a docked pose with a slightly worse binding energy of −8.5 kcal/mol, mainly due to the formation of slightly weaker π-π hydrophobic interactions.

Figure 4.

Docked poses of compounds 10 (green carbon atoms) and 12 (pink carbon atoms) in the 5-HT6 receptor (grey carbon atoms, colored helices and loops). Key hydrogen bonding interactions are depicted by the yellow dashed lines, salt bridges by the pink dashed lines and aromatic hydrogen bonds by the blue dashed lines.

Overall, the serotonin 5-HT6 receptor target gives better predicted binding energies for the conformationally rigid ligand set than the D1 receptor, primarily due to the formation of a stronger protonated N–Asp salt bridge and π-π hydrophobic interactions. These computational outcomes are in accord with the trend observed for the experimental binding affinities, which depict significantly enhanced activity and selectivity for the 10 - 13 ligand set towards the 5-HT6 receptor in comparison with D1.

3. CONCLUSIONS

Compounds containing the novel 1,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine framework were synthesized via the use of direct arylation methodology. We found that the key direct arylation reaction was problematic via the use of microwaves and was time sensitive under thermal conditions; we optimized the reaction with compound 8 as substrate under thermal conditions with a 2 hour reaction time. It is expected that these optimized conditions will be applicable to the synthesis of a variety of other 1,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepines (i.e. with more diverse aryl substituents).

Compounds 10 - 13 represent rigidified analogs of 1-phenylbenzazepines, such as SKF 38393, SKF 67650 and SCH 12679 – classical selective D1-like receptor ligands. Evaluation of the compounds at serotonin, adrenergic and dopamine receptors revealed a lack of significant affinity for D1-like receptors upon rigidification. However the rigidified ligands display selective affinity for the 5-HT6 receptor - an unexpected finding, especially given the reported D1-like receptor selectivity of SKF 38393 and similar 1-phenylbenzazepines at 5-HT receptors (data available online at the PDSP database - https://pdsp.unc.edu/databases/pdsp.php).

Docking studies with the rigidified analog compounds 10 – 13 generate bound poses involving key receptor-ligsnd interactions, including the quaternary nitrogen - aspartate salt bridge, π-π interactions between the 1-phenylbenzazepine aryl rings and phenylalanine residues as well as aromatic H-bonds. The predicted binding energies of these ligands give a similar trend as that obtained from the experimental data with the four tested ligands displaying selectivity for the 5-HT6 receptor over D1. In comparison to SKF 38393, the reduced D1 affinity for the rigidified compounds 10 – 13 may be due to weaker salt bridge, hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. In contrast, compounds 10 – 13 generate docked poses with better binding energies compared to SKF 38393 in the 5-HT6 receptor due to the formation of stronger π-π hydrophobic contacts.

This study has resulted in the serendipitous identification of a new 5-HT6 receptor selective scaffold, obtained via rigidification of the D1 receptor selective 1-phenylbenzazepine template. Important ligand-receptor interactions that contribute to 5-HT6 receptor affinity and selectivity versus D1 have been revealed from docking studies. A number of selective 5-HT6 receptor ligands are known, many of which contain an arysulfonyltryptamine motif.(Glennon et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2000) 5-HT6 receptor antagonists are promising as procognitive agents in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.(Benhamu, Martin-Fontecha, Vazquez-Villa, Pardo, & Lopez-Rodriguez, 2014). Interestingly, 5-HT6 receptor agonists have also been reported to display procognitive effects and also appear to to be promising as agents to treat depression and obesity.(Karila et al., 2015) Compounds such as 10 and 12 are structurally unique 5-HT6 receptor ligands (possessing at least 15-fold selectivity versus the other receptor tested). These novel compounds may serve as starting points for further refinement as useful tools to support our understanding of 5-HT6 receptor function and as new leads for drug discovery efforts involving 5-HT6 receptor targeting.

4. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

4.1. General synthetic experimental procedures

Unless otherwise stated, chemicals were purchased from Fischer Scientific (USA) and were used without further purification. Reactions were carried out in air-dried glassware under a nitrogen atmosphere. HRESIMS spectra were obtained using an Agilent 6520 QTOF instrument. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded using Bruker DPX-600 spectrometer (operating at 400 or 600 MHz for 1H; 100 or 150 MHz, respectively, for 13C) using CDCl3, Acetone-d6 or DMSO-d6 as solvents. Tetramethylsilane (δ 0.00 ppm) served as an internal standard in 1H NMR and CDCl3 (δ 77.0 ppm) in 13C NMR as solvent. Chemical shift (δ 0.00 ppm) values are reported in parts per million and coupling constants in Hertz (Hz). Splitting patterns are described as singlet (s), doublet (d), triplet (t), and multiplet (m). Reactions were monitored by TLC with Whatman Flexible TLC silica gel G/UV 254 precoated plates (0.25 mm). TLC plates were visualized by UV (254 nm). Silica gel column chromatography was performed with silica gel 60 (EMD Chemicals, 230–400 mesh, 0.063 mm particle size).

4.1.1. 1-(2-bromophenyl)-2-((3,4-dimethoxyphenethyl)amino)ethan-1-ol (6)

To a solution of epoxide (5) (25 mmol, 1 equiv.) and commercially available amine (4) (38 mmol, 1.5 equiv.) in anhydrous THF (100 mL) was slowly added Bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide lithium (27.5 mmol, 1.1 equiv.). The mixture was refluxed for 24 h and the reaction progress was monitored via TLC. After completion of the reaction, THF was evaporated and the reaction mixture was quenched with saturated NaHCO3 (25 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic phase was dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated to give a viscous liquid. The impure residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (2% MeOH/DCM) to give 6. Yield: 56%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.74 (m, 1H), 7.56 (m, 1H), 7.43 (m, 1H), 7.22 (dd, J = 7.2, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (m, 2H), 6.79 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 5.14 (m, 1H), 4.84 (br. s, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.14 (m, 1H), 3.01 (m, 2H), 2.84 (m, 2H), 2.66 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 149.1, 147.5, 141.2, 132.6, 132.5, 128.9, 127.7, 121.7, 121.6, 120.7, 112.2, 111.5, 71.7, 70.1, 62.2, 60.4, 55.9, 33.1. HRESIMS calculated for C18H22BrNO3 [M+H]+ 379.0783, found 379.0812.

4. 1.2. 1-(2-bromophenyl)-7,8-dimethoxy-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzo[d]azepine (7)

Amino-alcohol (6) (14 mmol, 1 equiv.) was dissolved in TFA (30 mL) and 18 M H2SO4 (cat.) was added to the solution. The mixture was stirred for 5 h at rt. Anhydrous NaOAc (28 mmol, 2 equiv.) was added and stirred for an additional 15 min. TFA was evaporated and the solution neutralized with 14 M NH4OH to give a solid residue. The residue was dissolved in EtOAc (25 mL) and washed with water and brine. The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (2%MeOH/DCM) to furnish 7 as a white solid. Yield: 43%; mp 180.2−181.5 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 7.66 (d, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, J=7.8, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (dd, J=7.8, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.05 (s, 1H), 4.96 (d, J=9.0 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 3.87 (m, 1H), 3.69 (m, 1H), 3.58 (m, 1H), 3.57 (s, 3H), 3.42 (m, 1H), 3.31 (m, 1H), 3.03 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 148.2, 148.1, 138.8, 133.8, 131.5, 129.4, 129.3, 128.2, 124.7, 120.6, 113.7, 112.3, 56.0, 55.9, 50.4, 46.8, 45.3, 31.5. HRESIMS calculated for C18H20BrNO2 [M+H]+ 361.0677, found 361.0687.

4.1.3. tert-butyl 1-(2-bromophenyl)-7,8-dimethoxy-1,2,4,5-tetrahydro-3H-benzo[d]azepine-3-carboxylate (8)

Benzazepine 7 (6 mmol, 1 equiv.) was dissolved in DCM (50 mL). To the solution was added TEA (1.2 mL, 9 mmol, 1.5 equiv.) and boc anhydride (12 mmol, 2 equiv.) and the reaction stirred at room temperature until completion. The reaction solution was evaporated under vacuum. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (30%EtOAc/Hexanes) to give a white solid as final product. Yield: 46%, mp 69.7–71.1 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.60 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (m, 1H), 7.09 (m, 1H), 6.90 (dd, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (s, 1H), 6.40 (s, 1H), 4.86 (m, 1H), 4.02 (d, J=4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.76 (m, 2H), 3.63 (s, 3H), 3.52 (m, 1H), 3.22 (m, 1H), 2.94 (m, 1H), 1.25 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.4, 147.6, 147.3, 142.4, 132.9, 132.4, 131.1, 130.4, 128.1, 127.7, 124.1, 114.6, 114.0, 79.5, 55.92, 55.90, 51.7, 47.8, 46.6, 34.9, 28.3. HRESIMS calculated for C23H28BrNO4 [M+H]+ 461.1202, found 461.1422.

4.1.4. tert-butyl 6,7-dimethoxy-1,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-2H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine-2-carboxylate (9)

Pd(OAc)3 (0.22 mmol, 0.2 equiv.), (t-Bu)2PMeHBF4 (0.432 mmol, 0.4 equiv.), Pivalic acid (0.108 mmol, 0.1 equiv.) and K2CO3 (2.2 mmol, 2 equiv.) was dissolved in DMSO (10 mL) and mixture stirred at room temperature for 15 min under nitrogen. Boc protected benzazepine (8, 1.08 mmol) was dissolved in DMSO (5 mL) and added to the reaction mixture dropwise via a syringe. The reaction was heated to 120 ℃ and stirred until completion, as confirmed by TLC. After completion, the reaction was cooled to room temperature and filtered via vacuum filtration. Cold water was added to the DMSO solution containing the product. The product precipitated as an off-white solid. Yield: 52%, mp 163.8–166 °C. mixture of rotamers. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.12 (m, 1H), 7.80 (m, 1H), 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.33 (m, 1H), 7.31 (m, 1H), 6.90 (s, 1H), 4.68 (m, 2H), 4.05 (m, 1H), 3.96 (s, 3H), 3.93 (s, 3H), 3.14 (m, 2H), 2.87 (m, 2H), 1.60 (m, 9H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 152.6, 143.9, 140.2, 137.5, 133.7, 132.1, 128.8, 127.7, 127.2, 124.1, 119.5, 112.7, 82.7, 60.3, 56.6, 37.0, 28.7, 28.3. HRESIMS calculated for C23H27NO4 [M+H]+ 381.1940, found 381.1944.

4.1.5. 6,7-dimethoxy-2,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine (10)

Compound 9 (0.92 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (10 mL) and to the solution was added TFA (20% in DCM). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. Completion of the reaction was confirmed by TLC. The reaction mixture was concentrated under vacuum. To the residue, was added saturated NaHCO3 (40 mL) to obtain an off-white solid which was further purified by silica gel column chromatography (40%EtOAc/Hexanes) to give compound 10 as a white solid. Yield: 52%, mp 163.8–166 °C. Rotamers observed- data for major rotamer is provided. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.03 (m, 1H), 7.38 (m, 1H), 7.32 (m, 1H), 7.23 (m, 1H), 6.58 (s, 1H), 4.58 (br. s, 1H), 4.03 (m, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.71 (m, 1H), 3.41 (m, 1H), 3.16 (m, 1H), 2.70 (m, 2H), 2.35 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 151.9, 144.2, 143.4, 140.2, 139.5, 134.4, 133.5, 127.8, 126.8, 123.9, 123.7, 112.3, 60.30, 56.4, 51.6, 50.7, 48.8, 37.8. HRESIMS calculated for C18H19NO2 [M+H]+ 281.1416, found 281.1500.

4.1.6. General procedure for O-demethylation

Methoxylated substrate (mmol, 1 equiv.) was dissolved in DCM (20 mL) and cooled in ice bath. BBr3 (mmol, 4 equiv.) was added to the solution slowly and the reaction stirred for 18 h. After completion, cold water was added to the reaction and the mixture allowed to stir for 30 min. The resulting precipitate was filtered and dried to give the purified O-demethylated product.

4.1.7. 2,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine-6,7-diol (11)

Compound 11 was synthesized from compound 10 (0.36 mmol) using the general procedure for demethylation. The final pure product was obtained as a gray solid. Yield: 54%, mp 187.3–192.1 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.03 (br. s, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.29 (s, 1H), 6.64 (s, 1H), 4.25 (m, 1H), 4.01 (m, 1H), 3.60 (m, 1H), 3.28 (m, 1H), 3.17 (m, 1H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.58 (m, 3H).13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 146.4, 145.0, 142.6, 141.3, 140.6, 136.3, 128.3, 127.7, 126.5, 124.7, 123.7, 115.4 49.1, 47.5, 45.2, 31.4. HRESIMS calculated for C16H15NO2 [M+H]+ 253.1103, found 253.1112.

4.1.8. 6,7-dimethoxy-2-methyl-2,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine (12)

Formaldehyde solution (vol, mmol, 1.2 equiv.) and NaBH(OAc)3 (mmol, 4 equiv.) was added to the solution of 10 in acetonitrile (vol) at room temperature. The reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight. The resulting solid was filtered via vacuum filtration to give a clear filtrate which was concentrated under vacuum. The resulting residue was dissolved in EtOAc (30 mL) and washed with saturated NaHCO3 (20 mL). The organic layer was dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuum to obtain compound 12. Yield: 78%, mp 168.3–170.6 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.02 (d, J= 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (m, 1H), 7.31 (m, 1H), 7.24 (m, 1H), 6.57 (s, 1H), 4.06 (m, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.40 (m, 1H), 3.21 (m, 1H), 3.05 (m, 1H), 2.62 (m, 1H), 2.49 (s, 3H), 2.24 (m, 1H), 1.88 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 151.8, 145.2, 143.1, 140.3, 139.8, 134.7, 133.2, 127.6, 126.7, 124.0, 123.6, 111.8, 60.7, 60.3, 57.7, 56.4, 48.0, 47.7, 35.2. HRESIMS calculated for C19H21NO2 [M+H]+ 295.1572, found 295.1560.

4.1.9. 2-methyl-2,3,4,11b-tetrahydro-1H-fluoreno[9,1-cd]azepine-6,7-diol (13)

Compound 13 was synthesized from compound 12 (0.34 mmol) following the general procedure for demethylation. Off-white solid; Yield: 46%, mp 194.2–196.5 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.99 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (m, 1H), 7.24 (m, 1H), 6.56 (s, 1H), 4.02 (m, 1H), 3.10 (m, 2H), 2.56 (m, 1H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 2.28 (m, 2H), 1.86 (m, 2H).13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 144.4, 144.0, 141.4, 140.0, 127.64, 127.4, 126.3, 126.1, 124.4, 123.47, 123.41, 115.0, 67.3, 57.9, 47.3, 36.1, 31.2. HRESIMS calculated for C17H17NO2 [M+H]+ 267.1259, found 267.1264.

4.2. Biological assays

All receptor binding assays were performed by the Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). Complete details of the assays performed may be found online in the PDSP assay protocol book (http://pdsp.med.unc.edu/PDSP%20Protocols%20II%202013-03-28.pdf).

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible by Grant Number 1SC1DA049961-01 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or its divisions. Ki determinations, and receptor binding profiles were generously provided by the National Institute of Mental Health’s Psychoactive Drug Screening Program, Contract # HHSN-271-2008-00025-C (NIMH PDSP). The NIMH PDSP is directed by Bryan L. Roth MD, PhD at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Project Officer Jamie Driscol at NIMH, Bethesda MD, USA. For experimental details please refer to the PDSP website http://pdsp.med.unc.edu/ and click on “Binding Assay” or “Functional Assay” on the menu bar. This work does not have any conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Ashby FG, Valentin VV, & von Meer SS (2015). Differential effects of dopamine-directed treatments on cognition. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 11, 1859–1875. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S65875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asin KE, Domino EF, Nikkel A, & Shiosaki K (1997). The selective dopamine D1 receptor agonist A-86929 maintains efficacy with repeated treatment in rodent and primate models of Parkinson’s disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 281(1), 454–459. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9103530 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C (1987). Endogenous renal dopamine and control of blood pressure. Clin Exp Hypertens A, 9(5–6), 955–975. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3304731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhamu B, Martin-Fontecha M, Vazquez-Villa H, Pardo L, & Lopez-Rodriguez ML (2014). Serotonin 5-HT6 receptor antagonists for the treatment of cognitive deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease. J Med Chem, 57(17), 7160–7181. doi: 10.1021/jm5003952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger JG, Chang WK, Clader JW, Hou D, Chipkin RE, & McPhail AT (1989). Synthesis and receptor affinities of some conformationally restricted analogues of the dopamine D1 selective ligand (5R)-8-chloro-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-3-methyl-5-phenyl- 1H-3-benzazepin-7-ol. J Med Chem, 32(8), 1913–1921. doi: 10.1021/jm00128a038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruana MP, Heber M, Brigden G, & Raftery EB (1987). Effects of fenoldopam, a specific dopamine receptor agonist, on blood pressure and left ventricular function in systemic hypertension. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 24(6), 721–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03237.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary S, & Harding WW (2011). Synthesis of C-Homoaporphines via Microwave-Assisted Direct Arylation. Tetrahedron, 67(3), 569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.11.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary S, Pecic S, Legendre O, & Harding WW (2009). Microwave-Assisted Direct Biaryl Coupling: First Application to the Synthesis of Aporphines. Tetrahedron Lett, 50(20), 2437–2439. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherezov V, Rosenbaum DM, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SG, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, … Stevens RC (2007). High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science, 318(5854), 1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AH, McCorvy JD, Watts VJ, & Nichols DE (2011). Assessment of dopamine D(1) receptor affinity and efficacy of three tetracyclic conformationally-restricted analogs of SKF38393. Bioorg Med Chem, 19(18), 5420–5431. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.07.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilam D, Clements KV, & Szechtman H (1991). Differential effects of D1 and D2 dopamine agonists on stereotyped locomotion in rats. Behav Brain Res, 45(2), 117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80077-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glennon RA, Siripurapu U, Roth BL, Kolanos R, Bondarev ML, Sikazwe D, … Dukat M (2010). The medicinal chemistry of 5-HT6 receptor ligands with a focus on arylsulfonyltryptamine analogs. Curr Top Med Chem, 10(5), 579–595. doi: 10.2174/156802610791111542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Vera JA, Medina RA, Martin-Fontecha M, Gonzalez A, de la Fuente T, Vazquez-Villa H, … Lopez-Rodriguez ML (2017). A new serotonin 5-HT6 receptor antagonist with procognitive activity - Importance of a halogen bond interaction to stabilize the binding. Sci Rep, 7, 41293. doi: 10.1038/srep41293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren TA, Murphy RB, Friesner RA, Beard HS, Frye LL, Pollard WT, & Banks JL (2004). Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 2. Enrichment factors in database screening. J Med Chem, 47(7), 1750–1759. doi: 10.1021/jm030644s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karila D, Freret T, Bouet V, Boulouard M, Dallemagne P, & Rochais C (2015). Therapeutic Potential of 5-HT6 Receptor Agonists. J Med Chem, 58(20), 7901–7912. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd DL, Weinstock J, Wise M, Gessner GW, Sawyer JL, & Flaim KE (1986). Synthesis and dopaminergic binding of 2-aryldopamine analogues: phenethylamines, 3-benzazepines, and 9-(aminomethyl)fluorenes. J Med Chem, 29(10), 1904–1912. doi: 10.1021/jm00160a018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafrance M, & Fagnou K (2006). Palladium-catalyzed benzene arylation: incorporation of catalytic pivalic acid as a proton shuttle and a key element in catalyst design. J Am Chem Soc, 128(51), 16496–16497. doi: 10.1021/ja067144j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Q, Johnson K, Morgan PS, Grenesko EL, Molnar CE, Anderson B, … George MS (2007). A single 20 mg dose of the full D1 dopamine agonist dihydrexidine (DAR-0100) increases prefrontal perfusion in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res, 94(1–3), 332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutschler NH, & Bergman J (2002). Effects of chronic administration of the D1 receptor partial agonist SKF 77434 on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 160(4), 362–370. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0976-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieoullon A, & Coquerel A (2003). Dopamine: a key regulator to adapt action, emotion, motivation and cognition. Curr Opin Neurol, 16 Suppl 2, S3–9. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15129844 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnala S, & Harding WW (2013). A New Route to Azafluoranthene Natural Products via Direct Arylation. European J Org Chem, 3013(6), 1107–1115. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201201190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascol O, Blin O, Thalamas C, Descombes S, Soubrouillard C, Azulay P, … Nutt JG (1999). ABT-431, a D1 receptor agonist prodrug, has efficacy in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol, 45(6), 736–741. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW (2003). Dopamine and cognition. Curr Opin Neurol, 16 Suppl 2, S1–2. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15129843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J (1984). The dopaminergic system in the periphery. J Pharmacol, 15(4), 401–414. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6098788 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SE, Aviles-Garay FA, Chakraborti R, Nichols DE, Watts VJ, & Mailman RB (1995). Synthesis and evaluation of 6,7-dihydroxy-2,3,4,8,9,13b-hexahydro-1H- benzo[6,7]cyclohepta[1,2,3-ef][3]benzazepine, 6,7-dihydroxy- 1,2,3,4,8,12b-hexahydroanthr[10,4a,4-cd]azepine, and 10-(aminomethyl)-9,10- dihydro-1,2-dihydroxyanthracene as conformationally restricted analogs of beta-phenyldopamine. J Med Chem, 38(13), 2395–2409. doi: 10.1021/jm00013a015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y, Dukat M, Slassi A, MacLean N, Demchyshyn L, Savage JE, … Glennon RA (2000). N1-(Benzenesulfonyl)tryptamines as novel 5-HT6 antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 10(20), 2295–2299. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00453-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Jiang Y, Ma J, Wu H, Wacker D, Katritch V, … Xu HE (2013). Structural basis for molecular recognition at serotonin receptors. Science, 340(6132), 610–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1232807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WL, Burnett DA, Spring R, Greenlee WJ, Smith M, Favreau L, … Lachowicz JE (2005). Dopamine D1/D5 receptor antagonists with improved pharmacokinetics: design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of phenol bioisosteric analogues of benzazepine D1/D5 antagonists. J Med Chem, 48(3), 680–693. doi: 10.1021/jm030614p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]