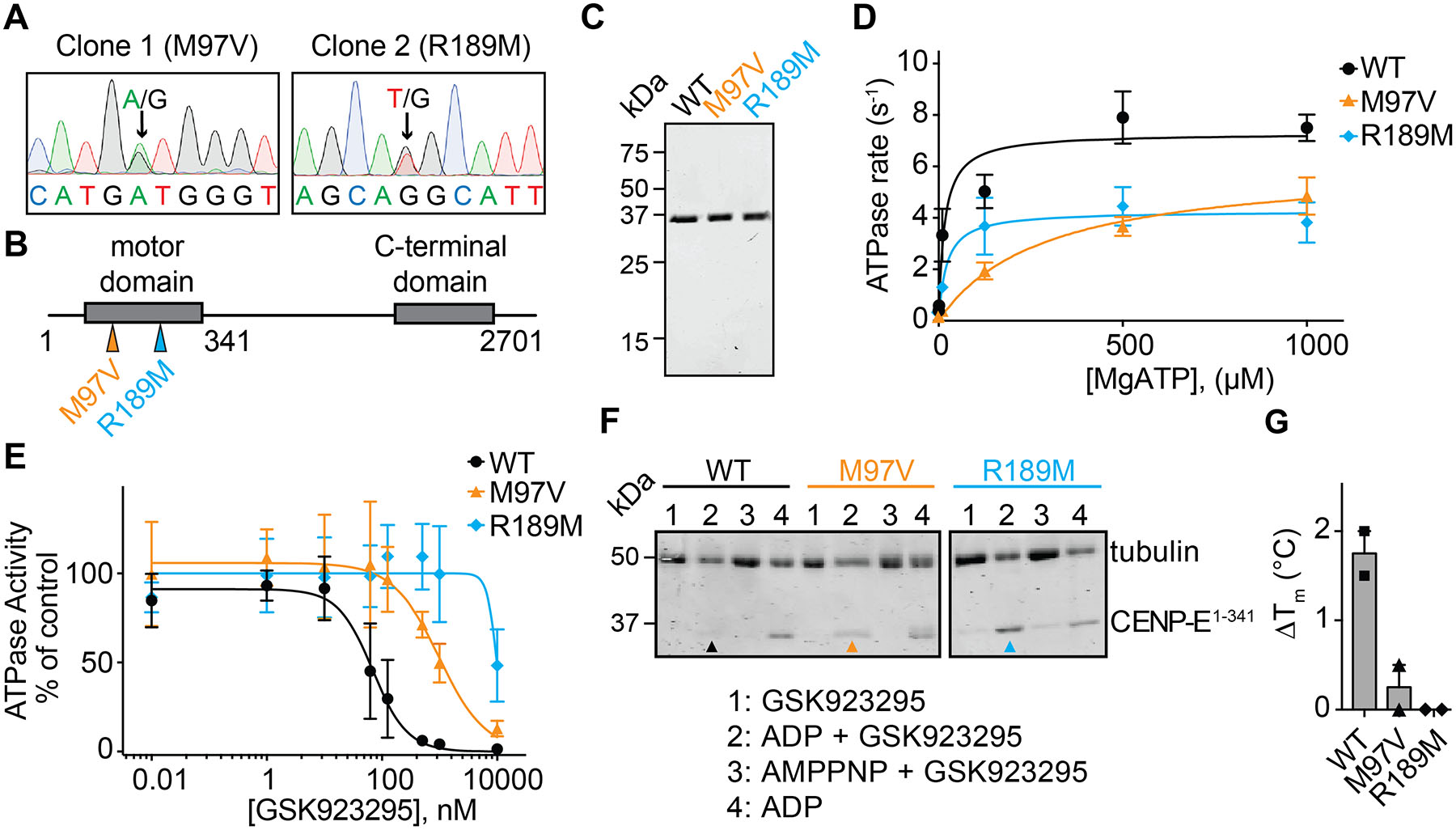

Figure 2. Characterizing resistance to GSK923295 in diploid cells.

(A) Sanger sequencing traces of genomic DNA encoding CENPE kinesin domain in two GSK923295-resistant HCT116 clones. Positions of heterozygous mutations are indicated (black arrows). Sequences are shown in 5’−3’ direction of the coding strand.

(B) Schematic shows motor and C-terminal domains of the CENPE protein. Positions of identified mutations are shown (colored arrows). First and last residues of the full length CENPE protein and the site of truncation to generate the recombinant kinesin motor domain construct are also indicated (not to scale).

(C) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified wild-type (WT) and mutant (M97V and R189M) CENPE constructs (aa 1–341, Coomassie Blue).

(D) ATP-concentration dependence of the steady-state activity of wild-type and mutant CENPE motor domain constructs. Graph shows values fit to a Michaelis-Menten equation (WT: kcat = 7.5 ± 0.5 s−1, KM = 25 ± 18 μM; M97V: kcat = 6.1 ± 0.9 s−1, KM = 294 ± 58 μM; R189M: kcat = 4.3 ± 0.8 s−1, KM = 21 ± 2 μM, average ± s.d., n=3).

(E) GSK923295 concentration-dependent inhibition of microtubule-stimulated ATPase activity of recombinant CENPE kinesin motor domain constructs. Graph shows values fit to a sigmoidal dose-response equation (IC50 WT: 77 ± 60 nM, M97V: 813 ± 167 nM, R189M: n.d., average values ± s.d., 2 mM MgATP, n=3).

(F) SDS-PAGE analysis of soluble supernatant fractions from a microtubule co-sedimentation assay. CENPE motor domains in the presence of GSK923925 and ADP are indicated with colored arrows (WT: black, M97V: orange, R189M: cyan). Source gels are shown in Figure S2C.

(G) Change in the heat-induced unfolding (∆Tm) of the recombinant CENP-E motor domain constructs in the presence of GSK923295 (50 µM) in comparison to vehicle control (DMSO, 1%; mean ± range, n = 2).