Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of the technologies we have developed to control proteins with light. First, we focus on the LOV domain, a versatile building block with reversible photo-response, kinetics tunable through mutagenesis, and ready expression in a broad range of cells and animals. Incorporation of LOV into proteins produced a variety of approaches: simple steric block of the active site released when irradiation lengthened a linker (PA-GTPases), reversible release from sequestration at mitochondria (LOV-TRAP), and Z-lock, a method in which a light-cleavable bridge is placed where it occludes the active site. The latter two methods make use of Zdk, small engineered proteins that bind selectively to the dark state of LOV. In order to control endogenous proteins, inhibitory peptides are embedded in the LOV domain where they are exposed only upon irradiation (PKA and MLCK inhibition). Similarly, controlled exposure of a nuclear localization sequence and nuclear export sequence is used to reversibly send proteins into the nucleus. Another avenue of engineering makes use of the heterodimerization of FKBP and FRB proteins, induced by the small molecule rapamycin. We control rapamycin with light or simply add it to target cells. Incorporation of fused FKBP-FRB into kinases, guanine exchange factors, or GTPases leads to rapamycin-induced protein activation. Kinases are engineered so that they can interact with only a specific substrate upon activation. Recombination of split proteins using rapamycin-induced conformational changes minimizes spontaneous reassembly. Finally, we explore the insertion of LOV or rapamycin-responsive domains into proteins such that light-induced conformational changes exert allosteric control of the active site. We hope these design ideas will inspire new applications and broaden our reach towards dynamic biological processes that unfold when studied in vivo.

Keywords: Optogenetics, Chemogenetics, LOV, RapR, LOVTRAP, Z-lock, Zdk, Engineered extrinsic disorder

1. Introduction

In this chapter we will provide a brief overview of the approaches we have developed to control proteins with light, in single cells and in animals. Most of the methods we will describe make use of the light-sensing domain that plants employ for phototropism, the light oxygen voltage domain (LOV2, from Avena sativa) [1, 2]. As we will show, it is a versatile building block that can be the basis of designs with complementary strengths, providing access to diverse protein structures. When irradiated between 400 and 500 nm, the LOV domain undergoes a dramatic conformational change that affects several portions of its structure [2–4]. Our methods harness the light-induced unwinding of the Jα helix (Fig. 1a). LOV is well suited for incorporation into different target proteins: the Jα helix is positioned at the C terminus where it can be fused to targets. Because the N and C termini are close together, LOV can be spliced into surface loops of target proteins, and the Jα helix can withstand substantial structure manipulation while maintaining light-controlled unfolding. The light-absorbing flavin cofactor of LOV is incorporated during protein synthesis, making LOV a good choice for optogenetic tools to be used in animals.

Fig. 1.

(a) The LOV2 domain. The green globular portion contains a flavin that absorbs light between 400 and 500 nm. Light absorption initiates changes in structure that ultimately lead to unwinding of the Jα helix (blue). This helix is at the C terminus of LOV2 where it can readily be appended to target proteins. (b) Protein photoactivation using the LOV domain as a steric block. The Jα helix is fused to the N terminus of the protein of interest (POI). When the Jα helix is coiled, LOV covers the active site of the POI. Upon irradiation the Jα helix unwinds, placing the LOV globular domain at the end of a longer linker and freeing the POI active site

Although LOV undergoes its light-induced conformational change in less than 2 ms [5], it returns to its dark state with a half-life of 27 s [6]. This limits the precision with which the kinetics of protein activity can be controlled, and also limits spatial control because substantial diffusion can occur while optogenetic analogs are turning off. Fortunately, point mutations can be used to adjust the rate of return to the dark state, producing half-lives ranging from 1.7 to 496 s [7, 8]. For precise kinetics the most rapid possible return is useful, but slow return kinetics can also be valuable. In animal studies, for example, they enable the activated state to be maintained simply using brief light pulses every ten minutes. The LOV conformational change has been induced using scanning confocal microscopes, simple mercury arc lamp illumination, turning on room lights, or more sophisticated equipment for precise control, including feedback from biological readouts to maintain fixed levels of activation [9]. Scanning instruments activate more slowly, as each pixel receives illumination only periodically during the scan.

LOV is always in equilibrium between the lit and dark states, with a Kd that is affected by light (i.e., irradiation shifts the Kd to favor the lit conformation). Because of this, most optogenetic protein analogs show a small amount of activity even under conditions meant to keep them in the off state. This “leakiness” is an important issue whose impact on biological studies depends on the effectiveness of inactivation, the increase in activity upon irradiation, and the biological characteristics of the target protein. In some cases, expression must be carefully controlled. A major advantage of optogenetics is the ability to suddenly trigger a change in protein activity, without giving the cell enough time to compensate, and expression of a leaky protein can lead to compensation. It is often valuable to stably express optogenetic proteins under the control of an inducible promoter, to prevent compensation, and for more convenient tissue culture. When the protein is expressed, cells can sometimes be cultured in TC dishes covered with foil, but it usually best to handle them solely under red light for 24 h or more before the experiment.

The LOV domain is a versatile building block that can be incorporated in proteins to produce very different photomodulation approaches, providing routes to widely varying protein structures. It can be used for photoactivation or photoinhibition, to send proteins to particular regions of the cell, to produce protein analogs that when activated act at multiple sites, or to control protein fragments that modulate endogenous targets. In the sections below we illustrate LOV’s versatility by contrasting different designs and highlighting considerations that determine when each can best be used.

2. Photoactivatable GTPases

In our first foray into the field, we sought to photoactivate a protein that was not an ion channel. Optogenetics to that point had used light-responsive ion channels to control nerve conduction, but we needed to manipulate GTPases, our primary research focus. We devised a strategy to reversibly position the LOV domain over the active site of the GTPase Rac1. We reasoned that a steric block, not dependent on specific binding interactions, could be applied to multiple closely related GTPases. The Jα helix was conveniently placed at the end of the LOV sequence so that we could attach it directly to the N terminus of Rac. The coiled helix would hold LOV over the active site, but unwinding the helix with light would produce a long linker that enabled Rac to interact with its downstream effectors. Optimizing the residues connecting the Jα helix to Rac1 produced the optogenetic protein analog we sought (photoactivatable Rac1, PA-Rac1) [10, 11] (Fig. 1b).

Using point mutations we knocked out upstream regulatory sites so that the protein would be controlled only by irradiation. Rac1 and other Rho family GTPases act at the plasma membrane but are sequestered in the cytoplasm when inactive. To focus our light where it was needed, and to eliminate the influence of mechanisms that translocate Rac1 into the membrane upon activation, we used a constitutively membrane-anchored version of Rac1. We did not yet know about LOV mutations that sped the return to the dark state (see above), so PA-Rac1 diffused from the point of activation over tens of seconds while returning to the dark state, limiting our spatial resolution to about 10 μm. Irradiating off the cell edge could narrow the region of the cell experiencing activation.

PA-Rac1 proved effective not only at controlling the morphology and movements of single mammalian cells [10, 11] but could also guide the movements of cells within Drosophila [11, 12] and zebrafish [13]. In the brains of mice, PA-Rac1 was used to control specific memories [14] or to modulate cocaine addiction [15]. Notably, Rac activation alone could in some cases guide cell movement, but sometimes Rac1 could produce protrusion only in specific subcellular regions (e.g., the front of polarized fibroblasts), likely because Rac1 signaling was superimposed on inhibitory programs or over-riding signals controlling polarization.

Because PA-Rac1 relied on a steric block of the active site, we initially thought the strategy would be applicable to many GTPases, but we were surprised to find that neither RhoA nor Cdc42 could be controlled. Although LOV’s block of the Rac1 active site did depend on the state of the Jα helix, molecular modeling and mutagenesis showed that it also relied on a surprising binding interaction between LOV and the Rac1 surface, even though these proteins are not thought to interact in nature. By mutating the surface of Cdc42 we could produce a PA-Cdc42 [10], but only at the expense of perturbing Cdc42 interactions that may determine target specificity. Only recently we have understood the LOV-GTPase interface sufficiently to predict which GTPases can be controlled by attaching LOV, and thereby produced new PA-GTPases (unpublished data).

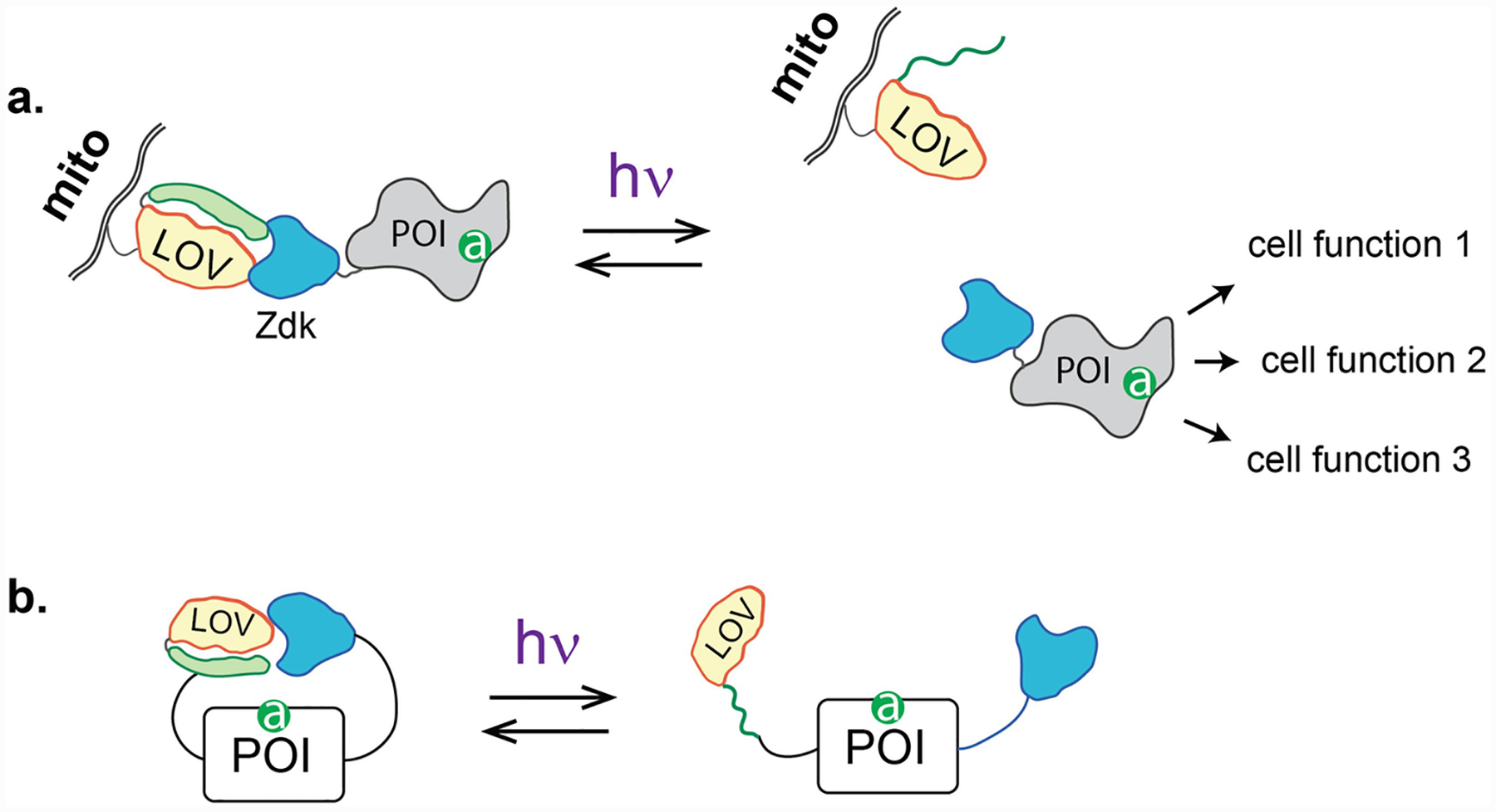

3. Applications of Zdk, a Building Block that Binds LOV only in the Dark

Given that the PA-Rac1 approach appeared initially to be suitable only for Rac1, we searched for a route to access other Rho GTPases. This family of molecules is regulated by controlling their access to the plasma membrane. When in the membrane they interact with effectors to exert activity but otherwise are held inactive in the cytosol, where the lipid anchors they use for membrane interaction are buried in guanine dissociation inhibitors. We took advantage of this regulatory mechanism by using light to control the GTPases’ subcellular distribution, and in the process generated a broadly applicable method much easier to apply to many targets. This method was named LOVTRAP [7, 8], because it was based on trapping the protein of interest (POI) at a subcellular site where it could not reach its targets (Fig. 2a). Trapping was effective in the dark, but the protein was reversibly released whenever the cell was irradiated. LOVTRAP depended on a new reagent named Zdk that bound selectively to the dark conformation of LOV. This was created by screening a large library based on the Z domain of protein A. A number of Zdk reagents, with differing affinity and binding sites on LOV, proved useful in different optogenetic methods [8, 16].

Fig. 2.

(a) LOVTRAP. LOV is anchored at a site in the cell away from the POI site of action. The POI is fused to Zdk, a small protein that binds LOV only in the dark. Upon irradiation, Zdk releases LOV, freeing the POI to move to its site of action. Rather than controlling the localization of active protein, LOVTRAP releases an active protein that is free to act at multiple sites. (b) Z-lock. LOV and Zdk are attached to the N and C termini of the target protein, positioned so they block the active site when they are bound to one another. Irradiation breaks the LOV-Zdk linkage, freeing the active site. The papers describing LOVTRAP and Z-lock provide a library of Zdk molecules with varying affinity

In the LOVTRAP method, Zdk was appended to the POI, and the LOV domain was anchored at mitochondria. In the dark, the POI was sequestered at mitochondria, where it could not access its targets (e.g., GEFs and GTPases that act at the plasma membrane). Irradiation broke the linkage between the POI-Zdk fusion and LOV, releasing the POI. Proteins could also be anchored at other subcellular sites. LOVTRAP was especially useful because it could be applied to a wide range of protein structures; Zdk simply had to be attached to either the N or C terminus. Importantly LOVTRAP could overcome the “leakiness” that plagued other methods (see Subheading 1); LOV at the mitochondria could be expressed in excess over the POI so that there was always excess dark state LOV to trap the POI.

LOVTRAP had clear advantages and disadvantages. It worked well to precisely control the kinetics of protein activation, as illustrated by our studies of oscillations governing Rho signaling pathways [8]. However, because the POI had to diffuse from mitochondria to the target site, spatial accuracy was compromised. For large nerve cells, localized irradiation of mitochondria provided sufficient spatial control [17]. Some users reported incomplete release from mitochondria, preventing them from reaching effective concentrations of free POI. By attaching LOV to the POI, and Zdk to the sequestration site (reversing the positions described above), more complete release could be achieved, but at the expense of additional leakiness [7]. In this configuration, LOV had to be attached to the POI’s N terminus because all Zdk variants bind near LOV’s C terminus.

The Zdk reagent was also used in an approach called Z-lock (Fig. 2b) [16]. As in the PA-GTPases described above, the target’s active site was occluded by a reversible steric block. Zdk was attached to one terminus of the protein and LOV to the other. With appropriate linker length the Z-lock and LOV bound each other in the dark, forming a bridge over the active site that was broken upon irradiation. Unlike the steric blocking used in the PA-GTPases, Z-lock promises to be a versatile tool because it does not require specific interaction with any part of the target. Because modification of both termini is required, it will likely not be so useful in controlling intact protein analogs, but rather can be most readily applied to protein fragments with a single active site and a single activity (e.g., enzymes). To date, Z-lock has been applied to control the activity of the actin severing protein cofilin and αTat, a protein that acetylates microtubules. In some cases circular permutation may be useful to position the termini. Because the LOV-Zdk interaction in Z-lock is intramolecular, release in the light was not very effective. We produced a tool kit of Zdk reagents with reduced affinity that can be used to build other Z-lock proteins.

4. Loopology

We found that we could insert either the LOV domain or an engineered drug-responsive domain into proteins to allosterically control the active site (Fig. 3a). Insertion could be far from important binding sites, and in many cases the conformations induced by the inserted domain mimicked the native on and off conformations of the target protein. To confer response to either light or small molecules, engineered domains were inserted into small “tight loops” on the protein surface (Fig. 3b). These loops are an essential part of many secondary structure motifs, acting as short connecting strands between antiparallel helices, segments of a β-pleated sheet, and so on. These motifs are largely buried within proteins, but the tight loops often project out at the surface. A scan of structures in the protein database (PDB) revealed that tight loops are restricted to a narrow range of lengths. The insertable domains were selected or engineered so that the spacing between their N and C termini matched the length of typical tight loops (approximately 10 Å), enabling us to insert them into diverse protein structures. To date we have used two different insertable domains: For response to light we used the LOV domain, whose N and C termini are less than 15 Å apart (Fig. 3c, left). To cause proteins to respond to small molecules we used the 12-kDa FK506 binding protein (FKBP12), which binds to the membrane-permeable drug rapamycin. The rapamycin interaction mediates binding to a second protein, FRB, which for some targets was important to the activation mechanism (see below). The FKBP N terminus was truncated to bring the N and C termini within 7 Å, to make insertable FKBP (iFKBP) [18] (Fig. 3c, right). The rapamycin-responsive analogs were controlled by light using a “caged” analog of rapamycin (rapamycin bearing a light-cleavable protecting group) [19] (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 3.

(a) Loopology. For this approach, one first identifies surface loops that are allosterically connected to the active site, ideally far from any important binding sites. Domains can then be inserted into the loops to confer sensitivity to small molecules (uniRapR, small molecules induce protein activation), or to light (LOV, irradiation leads to protein inhibition). By using light to inhibit autoinhibitory domains, light-induced activation is possible. (b) Examples of surface loops that are part of secondary structure motifs. Antiparallel helices and other configurations span the interior of the protein and reach from surface loops to the active site. In some cases, perturbation of the surface loop travels through more than one such motif. (c) The spacing between LOV and uniRapR’s termini matches the length of surface loops

Fig. 4.

Variations on a theme—applications of iFKBP. (a) iFKBP binds FRB in the presence of the membrane-permeable small molecule rapamycin. “Caged” rapamycin, bearing a photocleavable protecting group, does not interact with the proteins until it is irradiated. (b) When iFKBP is introduced in an appropriate surface loop, it knocks out the activity of the modified protein. In the presence of rapamycin, this iFKBP binds coexpressed FRB, causing protein activation. (c) When the activated protein has multiple downstream effectors, FRB can be attached to one so that activation of the protein leads to interaction with only one specific downstream target. (d) The iFKBP and FRB groups can be fused to generate the uniRapR domain. Using this leads to less heterogeneous responses than when FRB and an iFKBP-POI fusion are coexpressed

When a tight loop was replaced with the LOV domain, dark state LOV could effectively substitute for the loop. Upon irradiation, the LOV Jα helix unwound, increasing the spacing across the loop and the disorder of the associated protein structure. Through proper selection of the insertion site, this disorder could be communicated to the active site, effectively inhibiting the target protein with light [20]. Molecular modeling, NMR, and crystallography studies indicated that target proteins were being driven between two energy minima, their naturally occurring active and inactive conformations [20].

Unlike LOV, insertion of the rapamycin-responsive iFKBP domain inhibited protein activity; Addition of rapamycin restored the target protein to normal (Fig. 4b). Molecular modeling of rapamycin-regulated kinases (RapR kinases) indicated that a mechanism similar to that of LOV insertion was at play. In the absence of rapamycin, iFKBP was loosely folded and had substantial molecular motion; this was transferred to a critical ATP binding site in the kinase, killing activity [18]. Rapamycin addition caused the iFKBP to fold tightly and bind coexpressed FRB protein, reducing molecular motion and thereby restoring the normal mobility of the ATP binding site. Activation was essentially irreversible, but the Karginov laboratory showed that a functionally silent mutation developed by Shokat et al. could be used to make RapR kinases susceptible to an inhibitor [21].

Our initial success with kinases led us to develop a straightforward way to identify insertion sites for diverse protein structures [22]. Briefly put, surface loops are identified through inspection or by calculating solvent exposure, and highly conserved loops are dropped from contention. The remaining loops are screened for allosteric interactions with the active site using either molecular dynamics simulations or a simpler approach based on the distance between internal residues. Optimization of the linkers connecting the inserted domain to the target is important, but initial screens can identify promising loops before optimization. This approach has been used for photoinhibition of GEFs, GTPases, and kinases, and for rapamycin activation of kinases and GEFs. By inhibiting the autoinhibitory domain, it was also possible to photoactivate Vav2.

There are now several variants of the rapamycin-mediated activation, each with unique abilities. By attaching FRB to a specific downstream target of an activatable kinase, we could direct the kinase to interact with only one specific target upon activation (Fig. 4c). This “rapamycin-regulated targeted activation of pathways” (RapRTAP) approach was used to show the different roles of p130Cas activation and focal adhesion kinase activation downstream of Src [23]. iFKBP was also fused to FRB to produce “uniRapR” kinases that could be used without coexpressing FRB (Fig. 4d) [24]. This eliminated heterogenous responses produced by variations in the relative expression of the two proteins. Finally, we used the iFKBP group to enhance the control of split proteins [25]. In a variety of techniques proteins are split into two parts that can be induced to reassemble and restore activity. Spontaneous reassembly, in the absence of stimulation, has been a persistent problem with these techniques. iFKBP and FRB were placed on the two protein halves to control reassembly with rapamycin (Fig. 5). Before rapamycin was added, the iFKBP domain partially unfolded the attached protein, so spontaneous reassembly was greatly reduced. This technique, known as SPELL, was used for a number of proteins, and specifically for light activation of Vav2.

Fig. 5.

SPELL. When iFKBP and FRB are placed on the two halves of a split protein, activity can be restored by adding rapamycin to reunite the halves. When not bound to rapamycin, the iFKBP causes partial unfolding of the half to which it is attached, reducing undesirable spontaneous reassembly

One advantage of these techniques is their essentially absolute specificity. Genetic manipulations lead to compensation, and drugs can usually not distinguish between very similar isoforms or structures. With the protein analogs described here only the modified protein is affected by light. We demonstrated the power of this specificity by making RapR analogs of very closely related Src family kinases (e.g., Fyn and Src, greater than 70% homology). Activation of each produced a strikingly different phenotype and translocated to different subcellular locations upon activation [26].

Photoinhibition, as opposed to photoactivation, presents unique challenges. With photoactivation, if the protein can be expressed at levels where “leakiness” has little effect, the cell can be considered unaffected prior to irradiation. In contrast, photoinhibitable protein analogs are active until they are turned off, so simple expression essentially produces reversible overexpression. In some cases (especially with GEFs) we have found that the cell compensates for fluorescent analog expression by downregulating the endogenous protein. In other cases, knockdown/rescue or replacement of endogenous genes with optogenetic analogs could be used. For photoactivated proteins, one can knock out upstream regulation through point mutation or truncation so that protein activity is solely in control of the user. For photoinhibitable proteins, it may instead be wise to leave regulation intact, as the protein analog will substitute for native protein.

5. Embedded Peptides

The Jα helix of the LOV domain can withstand extensive modifications without perturbing critical interactions that maintain helical structure in the dark state [27, 28]. This has been used for light-induced dimerization, by incorporating a peptide in the Jα helix where it is unable to interact with its binding partners while the helix is folded [27–31]. When light causes the helix to unwind, the peptide is freed to interact with another protein or peptide that is anchored at a specific site in the cell (e.g., the plasma membrane). This light-induced dimerization has been used to direct GEFs to the plasma membrane, where they interact with targets.

In another application, a nuclear import peptide was embedded in the helix such that it could interact with the nuclear import machinery only when Jα was unwound [32–36]. This construct was attached to proteins for light-controlled nuclear import. Leakiness occurred both because of LOV unfolding in the dark, and because of simple diffusion into the nucleus. This was controlled by including a weak nuclear export signal, always exposed, that could be overcome by the nuclear localization signal. The Zdk group was used to further reduce leakiness by anchoring it at the mitochondria [37]. In the dark, Zdk bound to the NLS-LOV combination; upon irradiation, the NLS was exposed and LOV was released by Zdk, too (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Controlling embedded peptides. (a) For photocontrol of nuclear import a nuclear localization sequence is embedded in the Ja helix where it is exposed only upon irradiation. To hold the construct out of the nucleus in the dark, a weaker nuclear export sequence is always exposed, and Zdk anchored at mitochondria binds LOV only in the dark. (b) Other peptides can be embedded in the helix as well, including inhibitors of endogenous proteins

Hiding peptides in the LOV domain presents an exciting path for future research. Biologists often seek the ability to inhibit specific proteins, but the use of photoinhibitable protein analogs is complicated by the presence of endogenous protein (see above). We have explored the photoactivation of inhibitory peptides as an alternative to photoinhibitable protein analogs [38] (Fig. 6b). Peptides that inhibit either myosin light chain kinase or protein kinase A were embedded in LOV where they could only interact with their targets upon irradiation. This enabled photoinhibition of endogenous kinases.

An attempt to inhibit a GTPase by using Z-lock to control a fragment of a downstream protein was less successful, and held a lesson for this approach. Although biochemical assays showed light-controlled binding to a GTPase region required for downstream interactions, no effect was seen in living cells. This was perhaps because fragments of downstream targets have to compete with endogenous molecules. In the future, it will be important to find inhibitors that can be expressed at effective levels while not producing effects due to leakiness.

6. Conclusion

This chapter was certainly not intended as a review but rather as a discussion of the things we have learned by developing and comparing designs. Hopefully it will spark new ideas, and the caveats and considerations we have discussed will save time for future protein engineers. These designs were made possible through the extensive help and collaboration of multiple friends and colleagues, to whom we are very grateful.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health for funding (GM-R35GM122596 to K.M.H.) and thank Andrei Karginov, Onur Dagliyan, and Brian Kuhlman for helpful suggestions.

References

- 1.Christie JM, Salomon M, Nozue K, Wada M, Briggs WR (1999) LOV (light, oxygen, or voltage) domains of the blue-light photoreceptor phototropin (nph1): binding sites for the chromophore flavin mononucleotide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:8779–8783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harper SM, Neil LC, Gardner KH (2003) Structural basis of a phototropin light switch. Science 301:1541–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swartz TE, Corchnoy SB, Christie JM, Lewis JW, Szundi I, Briggs WR et al. (2001) The photocycle of a flavin-binding domain of the blue light photoreceptor phototropin. J Biol Chem 276:36493–36500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zayner JP, Antoniou C, Sosnick TR (2012) The amino-terminal helix modulates light-activated conformational changes in AsLOV2. J Mol Biol 419:61–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eitoku T, Nakasone Y, Matsuoka D, Tokutomi S, Terazima M (2005) Conformational dynamics of phototropin 2 LOV2 domain with the linker upon photoexcitation. J Am Chem Soc 127:13238–13244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salomon M, Christie JM, Knieb E, Lempert U, Briggs WR (2000) Photochemical and mutational analysis of the FMN-binding domains of the plant blue light receptor, phototropin. Biochemistry 39:9401–9410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Hahn KM (2016) LOVTRAP: a versatile method to control protein function with light. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 73:21.10.1–21.10.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Vilela M, Winkler A, Tarnawski M, Schlichting I, Yumerefendi H et al. (2016) LOVTRAP: an optogenetic system for photo-induced protein dissociation. Nat Methods 13:755–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toettcher JE, Gong D, Lim WA, Weiner OD (2011) Light-based feedback for controlling intracellular signaling dynamics. Nat Methods 8:837–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu YI, Frey D, Lungu OI, Jaehrig A, Schlichting I, Kuhlman B et al. (2009) A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature 461:104–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu YI, Wang X, He L, Montell D, Hahn KM (2011) Spatiotemporal control of small GTPases with light using the LOV domain. Methods Enzymol 497:393–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, He L, Wu YI, Hahn KM, Montell DJ (2010) Light-mediated activation reveals a key role for Rac in collective guidance of cell movement in vivo. Nat Cell Biol 12:591–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo SK, Deng Q, Cavnar PJ, Wu YI, Hahn KM, Huttenlocher A (2010) Differential regulation of protrusion and polarity by PI3K during neutrophil motility in live zebrafish. Dev Cell 18:226–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi-Takagi A, Yagishita S, Nakamura M, Shirai F, Wu YI, Loshbaugh AL et al. (2015) Labelling and optical erasure of synaptic memory traces in the motor cortex. Nature 525:333–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietz DM, Sun H, Lobo MK, Cahill ME, Chadwick B, Gao V et al. (2012) Rac1 is essential in cocaine-induced structural plasticity of nucleus accumbens neurons. Nat Neurosci 15:891–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone OJ, Pankow N, Liu B, Sharma VP, Eddy RJ, Wang H et al. (2019) Optogenetic control of cofilin and TAT in living cells using Z-lock. Nat Chem Bio 15(12):1183–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takano T, Wu M, Nakamuta S, Naoki H, Ishizawa N, Namba T et al. (2017) Discovery of long-range inhibitory signaling to ensure single axon formation. Nat Commun 8:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karginov AV, Ding F, Kota P, Dokholyan NV, Hahn KM (2010) Engineered allosteric activation of kinases in living cells. Nat Biotechnol 28:743–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karginov AV, Zou Y, Shirvanyants D, Kota P, Dokholyan NV, Young DD et al. (2011) Light regulation of protein dimerization and kinase activity in living cells using photocaged rapamycin and engineered FKBP. J Am Chem Soc 133:420–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dagliyan O, Tarnawski M, Chu PH, Shirvanyants D, Schlichting I, Dokholyan NV et al. (2016) Engineering extrinsic disorder to control protein activity in living cells. Science 354:1441–1444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klomp JE, Huyot V, Ray AM, Collins KB, Malik AB, Karginov AV (2016) Mimicking transient activation of protein kinases in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:14976–14981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dagliyan O, Dokholyan NV, Hahn KM (2019) Engineering proteins for allosteric control by light or ligands. Nat Protoc 14:1863–1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karginov AV, Tsygankov D, Berginski M, Chu PH, Trudeau ED, Yi JJ et al. (2014) Dissecting motility signaling through activation of specific Src-effector complexes. Nat Chem Biol 10:286–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dagliyan O, Shirvanyants D, Karginov AV, Ding F, Fee L, Chandrasekaran SN et al. (2013) Rational design of a ligand-controlled protein conformational switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110:6800–6804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dagliyan O, Krokhotin A, Ozkan-Dagliyan I, Deiters A, Der CJ, Hahn KM et al. (2018) Computational design of chemogenetic and optogenetic split proteins. Nat Commun 9:4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu PH, Tsygankov D, Berginski ME, Dagliyan O, Gomez SM, Elston TC et al. (2014) Engineered kinase activation reveals unique morphodynamic phenotypes and associated trafficking for Src family isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:12420–12425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lungu Oana I, Hallett Ryan A, Choi Eun J, Aiken Mary J, Hahn Klaus M, Kuhlman B (2012) Designing photoswitchable peptides using the AsLOV2 domain. Chem Biol 19:507–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmerman SP, Kuhlman B, Yumerefendi H (2016) Engineering and application of LOV2-based photoswitches. Methods Enzymol 580:169–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guntas G, Hallett RA, Zimmerman SP, Williams T, Yumerefendi H, Bear JE et al. (2015) Engineering an improved light-induced dimer (iLID) for controlling the localization and activity of signaling proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:112–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallett RA, Zimmerman SP, Yumerefendi H, Bear JE, Kuhlman B (2016) Correlating in vitro and in vivo activities of light-inducible dimers: a cellular optogenetics guide. ACS Synth Biol 5:53–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strickland D, Lin Y, Wagner E, Hope CM, Zayner J, Antoniou C et al. (2012) TULIPs: tunable, light-controlled interacting protein tags for cell biology. Nat Methods 9:379–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Ventura B, Kuhlman B (2016) Go in! Go out! Inducible control of nuclear localization. Curr Opin Chem Biol 34:62–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niopek D, Wehler P, Roensch J, Eils R, Di Ventura B (2016) Optogenetic control of nuclear protein export. Nat Commun 7:10624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niopek D, Benzinger D, Roensch J, Draebing T, Wehler P, Eils R et al. (2014) Engineering light-inducible nuclear localization signals for precise spatiotemporal control of protein dynamics in living cells. Nat Commun 5:4404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lerner AM, Yumerefendi H, Goudy OJ, Strahl BD, Kuhlman B (2018) Engineering improved photoswitches for the control of nucleocytoplasmic distribution. ACS Synth Biol 7:2898–2907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yumerefendi H, Dickinson DJ, Wang H, Zimmerman SP, Bear JE, Goldstein B et al. (2015) Control of protein activity and cell fate specification via light-mediated nuclear translocation. PLoS One 10:e0128443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yumerefendi H, Wang H, Dickinson DJ, Lerner AM, Malkus P, Goldstein B et al. (2018) Light-dependent cytoplasmic recruitment enhances the dynamic range of a nuclear import photoswitch. Chembiochem 19:2898–2907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yi JJ, Wang H, Vilela M, Danuser G, Hahn KM (2014) Manipulation of endogenous kinase activity in living cells using photoswitchable inhibitory peptides. ACS Synth Biol 3:788–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]