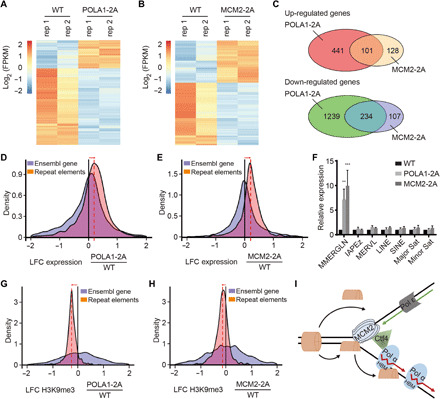

Fig. 6. Cells defective in parental histone transfer show defects in gene transcription and ERV silencing.

(A and B) Cluster analysis of differentially expressed genes between WT and POLA1-2A (A) and MCM2-2A (B) mutant mouse ES cells by RNA-seq. Results from two independent repeats (rep 1 and rep 2) were shown. FPKM, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads. (C) Venn diagram of up-regulated (top) and down-regulated (bottom) genes between POLA1-2A and MCM2-2A mutant mouse ES cells. (D and E) Changes in the transcription of transposable elements (TEs) in POLA1-2A (D) and MCM2-2A (E) relative to WT mouse ES cells. Histograms show the distributions of the log2 fold change (LFC) of repeat element expression in each mutant relative to WT cells. Orange, transcription of repetitive elements (Repbase with RNA-seq; POLA1-2A n = 2; MCM2-2A n = 2). Blue, transcription of Ensembl genes. (F) Expression analysis of repetitive elements in WT, POLA1-2A, and MCM2-2A mouse ES cells by quantitative PCR. MMERGLN-int (ERV1), IAPEz-int (ERVK), and MERVL-int (ERVL) representing different families of ERVs were tested. Data were plotted as means ± SEM from at least three independent repeats. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. (G and H) Changes in the enrichment of H3K9me3 in POLA1-2A (G) and MCM2-2A (H) relative to WT mouse ES cells. Histograms show the distributions of the LFC of H3K9me3 density in POLA1-2A and MCM2-2A mutants relative to WT cells. (I) A model for the role of POLA1 in parental histone transfer.