Abstract

This study aims to clarify the roles of immersion and distancing (that is, reflection on an experience from an egocentric point of view or as an observer, respectively) on therapeutic change analyzing i) the evolution of these two perspectives across the resolution of a clinical problem, and ii) the relationship between immersion/distancing with symptoms and emotional arousal. We extracted all the passages of speech pertaining to the most relevant clinical problem of a good outcome case of depression undergoing cognitive-behavioral therapy. We assessed the distancing/immersion of these extracts using the Measure of Immersed and Distanced Speech, and emotional arousal with the Client Emotional Arousal Scale-III. The symptoms were assessed from the Beck Depression Inventory-II and Outcome Questionnaire-10.2. Immersion was associated with symptoms and negative emotions, while distancing was associated with clinical well being and positive emotions. Immersion was still dominant when depressive symptoms were below the clinical threshold. Clinical change was associated with a decrease in immersion and an increase in distancing. The dominance of immersion does not necessarily indicate a bad outcome.

Key words: Immersion, Distancing, Emotional arousal, Symptoms, Cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Introduction

When reflecting on personal experiences, individuals may assume two different perspectives: immersed or distanced (Kross, Gard, Deldin, & Clifton, 2012; Nigro & Neisser, 1983). When immersed, individuals reflect on their experience from a first person perspective, since the experiencing and reflecting selves coincide. The original thoughts, feelings, behaviors and events repeat themselves (e.g., My boyfriend said he wanted to pursue a new life, so I feel sad and unloved. I’ll never be happy.). In a distanced perspective, individuals reflect on their experience from an observer stance, i.e., the reflecting self is separated from the self that is experiencing. People can see themselves in the experience (e.g., I was exposed to lots of humiliations, which made me prone to think that others are better than me, or that I have no value.).

Several experimental studies have suggested that the perspective adopted in the reflection of negative experiences has different consequences in terms of well-being and mental health (e.g., Bruehlman-Senecal, Ayduk, & John, 2016; Cao & Decker, 2015; Kross et al., 2014; White, Kross, & Ducjworth, 2015; Kross et al., 2012; Mischkowski, Kross, & Bushman, 2012; Shepherd, Coifman, Matt, & Fresco, 2016). Mainly, distancing has been conceived as a psychological perspective that facilitates adaptive analysis and favors the capacity of modulating emotional arousal. Specifically, several studies have revealed that reflecting from a distanced perspective is associated with shorter duration of negative episodes (Verduyn, Mechelen, Kross, Chezzi, & Bever, 2012) and attenuation of emotional intensity (Kross et al., 2014; Kross et al., 2012), as well as better self-control in challenging situations (Mischkowski et al., 2012). Moreover, experimental studies have shown that as opposed to immersion, in distancing people focus on the broader and abstract context (e.g., Kross & Ayduk, 2011) and less on the specific feelings, thoughts and events of the experience that would intensify negative affect, allowing one to reconstruct negative feelings and to give meaning to the experience (Ayduk & Kross, 2010b; Kross & Ayduk, 2011; Kross et al., 2012). The distancing has proved beneficial regardless of the person’s age (e.g., Grossmann & Kross, 2014). All these results suggest that distancing, when compared with immersion, is associated with greater ability to regulate emotional arousal triggered by negative personal experiences. Accordingly, research on emotion regulation has been proposing the use of reappraisal strategies – which involve an observer stance – as ways of changing the emotional meaning of negative or threatening situations and achieving more adaptive emotional responses (Duckworth, Gendler, & Gross, 2016; Gross, 2015). Distancing has also been presented as a protective mechanism against depression. An experimental study with people with depressive symptoms revealed that, while analyzing negative feelings, changing from an immersed to a distanced perspective engendered lower arousal of emotions, lower frequency of depressotypic thoughts and higher probability of achieving insight and closure (Kross et al., 2012). Often the focus on specific internal states from an immersed perspective involves people in ruminative cycles, which are common in depression, while distancing would reduce rumination (e.g., Ayduk & Kross, 2010a; Kross et al., 2012).

On the basis of these observations, experimental studies consider distancing, in contrast to immersion, as a productive perspective when dealing with negative experiences, which stresses its potential role as a change mechanism in psychotherapy of depression. Indeed, some therapeutic modalities are based on a similar conceptualization of distanced self-reflection from specific interventions. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) encourages clients to assume such a decentered stance towards their personal experiences when restructuring negative thoughts and promoting therapeutic change (e.g., Beck, 2011). More specifically, clients are encouraged to view a belief as a hypothesis rather than as a fact, which involves distancing of oneself from a belief to allow a more broad and objective analysis of it. In this way, clients can progressively arrive at an alternative view of the experience, changing the belief. Consequently, the negative affect is reduced, emotional reactions become understandable, and new and more adaptive behaviors are adopted when they are confronted with day-to-day difficulties (DeRubeis, Webb, Tang, & Beck, 2010). The use of distancing to help clients regulate and modulate their affective reactions, also occur in other therapeutic models, such as emotion-focused therapy (EFT): when a client feels overwhelmed by painful emotions, therapists guide clients to observe inner feelings, while distancing language is encouraged (e.g., using his or her own name instead of I) in order to promote emotional regulation (Elliott, Watson, & Greenberg, 2004). Another example in CBT (Beck, 2011), but also in other types of therapy (e.g., Greenberg & Watson, 2006), is the assignment of awareness homeworks, in which the therapist suggests the client to observe his or her emotional reactions or actions between sessions, aiming to promote a better self-understanding and to perceive links between events, feelings, and behaviors.

Overall, immersion on negative contents is expected to be associated with more emotional arousal, while distancing is expected to be associated with less emotional arousal, namely of negative emotions, and so better wellbeing and more adaptive psychological states. This is in line with what we would expect from a good outcome case in psychotherapy: since the person will in the end be better prepared to deal with the problematic issues, he or she will be less emotionally aroused by them.

However, does this mean that emotional arousal is something to be avoided in therapy? Or does it mean that the decrease of emotional arousal is an expected outcome, but not necessarily a negative process? Several approaches and empirical findings attribute a positive role to emotional arousal. Different psychotherapeutic orientations, ranging from psychodynamic (Fosha, 2000), experiential (Greenberg, 2002), or CBT (Samoilov & Goldfried, 2000), have suggested that, in the initial phases of therapy, emotional arousal and its expression are necessary to promote change. The arousal of emotions has been frequently considered as a process that fosters the arousal of emotional structures and information, allowing for a greater awareness and facilitating the reattribution of meaning (e.g., Greenberg, Rice & Elliott, 1993; Pennebaker & Graybeal, 2001; Smyth, 1998; Wilson & Gilbert, 2008). It is also important to stress that there are experiential and cognitive-behavioral treatments, for example, in which emotional arousal of negative experiences is considered as a central part of a key process of change, namely, emotional processing (Greenberg, 2002; Greenberg & Safran, 1987; Rachman, 1980). Emotional processing involves, firstly, arousing emotions, as well as, experiencing or be in live contact with experience, which suggests immersion in emotional experience. Only then is possible, in emotional processing, the meaning-making of emotional experience, transforming the maladaptive emotions that underlie and influence how the client feels, thinks, and behaves (Elliott, Greenberg, Watson, Timulak, & Freire, 2013; Greenberg & Watson, 2006; Greenberg, 2010). Also Kennedy-Moore and Watson (2001) suggested that immersed emotional expression is beneficial as a first step toward change. Specifically, the contact with painful material leads to greater arousal of negative emotional states, and in several situations this will pave the way for a later understanding of the emotional pain as tolerable and acceptable, and for mastering negative feelings. Consequently, people feel encouraged to evaluate the meaning of the experience. Therefore, it can be argued that immersion may be a productive and necessary therapeutic process involving emotional arousal, and by which therapists and patients gain access to very painful experiences in order to allow further therapeutic work. This seems to be the case, for example, in the narrative retelling of traumatic episodes while working with patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (Foa, Zoellen, Feeny, Hembree, & Alvarez-Conrad, 2002; Jaycox, Foa, & Morral, 1998). This suggestion may seem consistent with some forms of therapy. For example, in CBT, therapists encourage clients to describe emotional events aiming to access their cognitive and emotional components, namely dysfunctional thoughts to be restructured (Beck, 2011). In line, EFT argues that clients need to get in touch with their core maladaptive states, in order to become aware of their internal states, and then to process and transform them. As the EFT motto claims, the only way out is through (Pascual-Leone & Greenberg, 2007).

Moreover, the encouraging of an immersed perspective is a procedure used when emotions are avoided (typically in clients distant from their emotions) (Elliott et al., 2004). Sometimes, people reflect according to a distanced perspective to avoid the psychological distress caused by painful emotions of negative events (e.g., Foa & Kozak, 1986). This strategy may be dysfunctional, once it complicates access to important information about the experience, hindering the long-term resolution of distress (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, & Strosahl, 1996; Kashdan, Barrios, Forsyth, Steger, 2006). In this sense, as immersion may be dysfunctional when leads to rumination and excessive negative affect (e.g., Ayduk & Kross, 2010a; Kross et al., 2012), distancing may also not always be adaptive in therapy when used to avoid the experience. In sum, in spite of the general trend accentuating the benefits of distancing and the negative consequences of immersion, there are also other findings suggesting that in some circumstances these effects can be quite the opposite. Thus, the role of immersion and distancing in psychotherapy needs to be further clarified.

Based on this previous research on emotional arousal and therapeutic models, we developed the following global hypothetical theoretical framework. On the one hand, immersion in negative experiences can lead to increase the arousal of painful emotions. On the other hand, the arousal of painful emotions can lead to increase immersion on negative experiences. However, both processes in the initial phase of therapy promote the contact with emotional experience, developing the awareness of the different facets of experience, which may justify, in some cases, an increase of specific or general clinical symptoms. Then, the change in reflection and in arousal is need. On the one hand, the greater awareness about experience may encourage the client to adopt a distanced perspective, leading to less emotional arousal of painful emotions. On the other hand, the reduction of emotional arousal of painful emotions, i.e., better ability of emotional regulation, facilitates the distancing when reflecting on negative experiences. Regardless of the process involved, we hypothesize greater distancing accompanied by less emotional arousal of negative emotions at a later stage of therapy. In a more general vein, one of the first steps of psychotherapy is sharing the content of negative experiences. This will create a high level of negative arousal and immersion while paving the way to the creation of a new awareness of one’s own experience – and therefore, promoting distancing in the later stages of therapy. However, this view still needs empirical support.

Furthermore, there are some key issues left unaddressed by previous experimental studies. First, most of these studies did not use clinical samples, and there has been no study focused on psychotherapy and its effects. Second, in these studies participants were assessed only once or over a period of a week or less (e.g., Mischkowski et al., 2012). Thus, it is important to develop longitudinal studies of psychotherapy cases analyzing immersed and distanced perspectives over longer periods of time, in order to test the relationship of these perspectives with emotional arousal and clinical change. Finally, previous studies assessed immersion and distancing using a self-report scale among participants after a reflection task of an experience (e.g., Kross et al., 2012; Mischkowski et al., 2012), or experimental manipulation from instructions provided to participants (e.g., Wang, Lin, Huang, & Yeh, 2012). We still lack an observational measure of distancing and immersion in order to study the therapeutic client’s discourse as it unfolds.

In this single case study, we aimed to analyze the development of immersion and distancing throughout a therapeutic process, as well as the relationship of both these perspectives with emotional arousal and depressive symptoms, using an observational measure based on procedures and characteristics of immersion and distancing extracted from previous studies. We selected a good outcome case of CBT, since, in this type of therapy, an observer stance towards personal experiences is promoted by the repeated reality testing of dysfunctional automatic thoughts (Beck, 2011). Therefore, we expected an increase of distancing over time, and a decrease of immersion. However, we had no specific anticipated hypothesis regarding the relative frequency of these two perspectives. In a perhaps simplistic reading of previous experimental studies, immersion can be regarded as a dysfunctional perspective (associated with rumination and high levels of negative affect), and therefore, we may expect a good outcome to be associated with very low frequency by the end of the therapy; on the other hand, therapy sessions may always involve some degree of immersion in problematic states. Therefore, it may be the case that some degree of immersion may always be needed. Thus, from the Simulation Modelling Analysis (SMA; Borckardt & Nash, 2014), as an advanced statistical program that uses a bootstrap sampling method allowing the control of autocorrelation, we will test the following main hypothesis: a) if, generally, immersion is associated with clinical problems, and distancing with overcoming those problems, then we expect to find high levels of immersion at beginning of therapy, and an increase of distancing throughout therapy, as well as a positive relationship between this pattern of evolution and symptomatic improvement; b) However, if immersion may be used in a productive way during therapy, then we expect to find high levels of immersion in different phases of therapy; c) Moreover, if distancing is associated with greater emotional control than immersion, then we expect that arousal of negative emotions to be negatively related with distancing and positively related with immersion.

Methods

Client

Laura (pseudonym), a 33 year old woman, married, with one daughter, was unemployed at the time of her participation in the ISMAI Depression Project (Decentering and Change in Psychotherapy) funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (Salgado, 2014). This is a randomized clinical trial that compared CBT and EFT for major depressive disorder (MDD). The following inclusion criteria were set: diagnosis of major depressive disorder, a global assessment of functioning higher than 50, and no medication. Exclusion criteria were: being under another form of treatment for depression; current or previous diagnosis of at least one of the following DSM–IV Axis I disorders: panic, substance abuse, psychosis, bipolar, eating disorder; or one of the following DSM–IV Axis II disorders: borderline, antisocial, or schizotypal personality disorder; or high risk of suicide. All these criteria were assessed by the Structural Clinical Interviews for the DSM-IV-TR I (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) and II (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams & Benjamin, 1997) and the Beck Depression Inventory- II (BDI-II) for the Portuguese population (Coelho, Martins, & Barros, 2002). Laura was diagnosed with moderate MDD and no other disorders, meeting all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria of the clinical trial. She was randomly assigned to CBT and attended 16 weekly sessions plus follow-up sessions at 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. As defined by the clinical trial protocol, all sessions were video recorded.

Psychological treatment, as well as the collection and processing of data for research purposes followed principles and standards included in the ethics code (American Psychological Association’s – APA – Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct, as well as the Code of Ethics of Portuguese Psychologists). In this sense, after receiving information about the purposes and procedures of the clinical trial, all clients gave their written consent for using their data in scientific publications.

At treatment termination, Laura had recovered and showed reliable and clinically significant change (Comer & Kendall, 2013) according to the cut-off score of 13 points on the Portuguese version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Coelho et al., 2002) and the Reliable Change Index of 7.75, calculated from the psychometric information on the BDI-II. More specifically, her pre-therapy BDI-II score was 31, which had dropped to zero by the end of therapy. This score on the BDI-II was maintained across all the available follow-up sessions, namely at 1, 3, 6 and 9 months after concluding therapy.

Therapist

Laura’s therapist was female, with 12 years of experience as a psychotherapist. She had a CBT background, and had received further training in the treatment manual used in this trial before starting to treat Laura. She also received weekly supervision for this case. The supervision was carried out in a group, made up of all the clinical trial´s therapists who followed the CBT protocol, and was leaded by the most experienced CBT therapist.

She followed a CBT protocol for the treatment of the depression (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). The 16- session protocol is based on the principle that the interpretations or cognitions about reality determine emotions and behaviors; consequently, dysfunctional interpretations of reality promote emotional disorders. This protocol includes cognitive and behavioral techniques. The purpose is to promote changes in emotions and behaviors by changing biased ways of seeing the world. This therapist received further training in the treatment manual and she also received weekly supervision for this case.

Process measures

Assimilation of Problematic Experiences Scale

This scale is used to assess the degree of resolution of a clinical problem measured by assimilation levels of the problematic experience, ranging from level 0 (the client is unaware of the problem) to level 7 (the client successfully uses solutions in new situations). Higher levels of assimilation mean higher levels of resolution (see Caro Gabalda & Stiles, 2009; Basto, Pinheiro, Stiles, Rijo, & Salgado, 2016). In this study, APES was used in order to ensure that immersion and distancing were analyzed across the therapeutic change of a clinical problem (from unresolved to resolved problem). See more details in Procedures (selection of the main clinical problem).

A study performed with a sample of 22 Portuguese clients diagnosed with major depression disorder (Basto, Stiles, Rijo, & Salgado, in press), showed a high interrater reliability (Cicchetti, 1994) on APES ratings [Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) ranged from ICC [2,2]=0.81 to ICC (2,2)=0.96].

Measure of Immersed and Distanced Speech

The MIDS was based on theoretical definition and relevant prior research (e.g., Kross et al., 2012; Ayduk & Kross, 2010b; Nigro & Neisser, 1983) for the identification of immersion and distancing from client speech. This is an observational measure that assesses immersion and distancing from client speech in transcribed sessions. The client’s speech is categorized according to five mutually exclusive categories: what statements and attributive statements (that represent immersed speech), insight statements and closure statements (distancing speech), and other statements (in situations in which none of the previous categories are applicable), as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Brief description of immersed and distanced speech categories.

| Type of speech | Categories | Contents | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immersed | What statements | Client describes a specific chain of events | He yelled at me and treated me badly |

| He told me to back off | |||

| Client describes specific and original thoughts or behaviors | I went to my room and cried for a long time | ||

| My work is worthless | |||

| Attributive statements | Client ascribes characteristics to self or others without explaining or providing reasons to them | He was mean | |

| I was kind of stupid | |||

| Client describes feelings or other internal states | I feel sad | ||

| I feel happy | |||

| I have a great pain and a permanent restlessness | |||

| Distanced | Insight statements | Client describes the causes underlying the event, his or her feelings, behaviors and cognitions | He does not respect me because I never established any limits |

| Client establishes relations between behaviors, feelings or cognitions | Maybe I reacted that way because I felt he rejected me | ||

| Client expresses new awareness about own behaviors, feelings or cognitions | It may have been somehow irrational but now I better understand my motivation then | ||

| Closure statements | Client indicates he or she assesses a past experience from a broad perspective, taking into account past and current experiences to make sense of feelings and experiences | I look back and I see that suffering had to do with how I interpreted criticisms. Now I know that critical remarks can be constructive and it does not mean that others do not like me | |

| Client establishes relations (contrasts or similitudes) between past and present behaviors, feelings or cognitions | Today I know that I’m valued by my father Today I barely hugged my father, whereas before we were like brothers | ||

| Client expresses present feelings or thoughts about past experience or situations | I thought about how glad I am that part of my past is over I see my past as a difficult moment of my life that brought implications in what I am today |

The study about MIDS’ validation is under preparation. Preliminary results revealed a high internal consistency for both immersion (α=.95) and distancing (α=.91). The interrater reliability (Hill & Lambert, 2004) for raters’ pairs was good to strong (Cohen´s Kappa ranged from .75 to .96).

Client Emotional Arousal Scale-III

The CEAS-III (Warwar & Greenberg, 1999) was developed to identify and assess the emergence of emotions based on the evaluation of audio or videotaped psychotherapy sessions. To assess the emotion and its valence, the client’s primary emotion in the session segment under evaluation was identified and categorized according to a list of 15 emotion categories, taking into account the client’s voice and body expressions.

Warwar and Greenberg (2000) found interrater reliability coefficients of .70 for modal and of 0.73 for peak arousal ratings.

Outcome measures

BDI-II

The BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996; Portuguese version by Coelho et al., 2002) is a self-report inventory designed to measure the severity of depression. Scores above 13 signify clinically significant levels of depression. This measure has an internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of .89. The psychometrics qualities found in the Portuguese version and American version were consistent (Coelho et al., 2002).

Outcome Questionnaire-10.2

The OQ-10.2 (Lambert et al., 1998) is a self-report inventory intended to assess general clinical outcome. This measure is a brief version (with 10 items) of OQ-45.2, which was translated and adapted to Portuguese by Machado and Fassnacht (2014). The total score may range from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate greater severity of clinical problems. This measure has an internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of .88 (Seelert, 1997) and a test– retest reliability of .62 (Lambert, Finch, Okiishi, & Burlingame, 2005).

The scores of the Portuguese OQ-10 for the entire sample of the clinical trial (n=64; Salgado, 2014), from which the case for this study was selected, show an internal consistency of .88 (Cronbach’s Alpha) and a test-retest reliability of .74 over a 1-week interval.

Procedures

Selection of the main clinical problem

Our analysis was restricted to the moments pertaining to the main clinical problem which was solved across therapy, since only this would allow us to focus on occasions during which negative contents were directly or indirectly involved from unresolved to resolved. Two judges were involved in this task: a PhD student and a Master’s degree student in clinical psychology with training and experience in CBT. Initially, they participated in a training phase that included reading and discussing journal articles and previous rating manuals, and practicing the coding procedures. This phase lasted about two months and was guided by a researcher who was expert in this type of procedure. The training phase was deemed concluded when the judges reached the reliability criterion in coding procedure, namely an Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) higher than.70 (considered high reliability by Hill & Lambert, 2004).

After a training phase, the judges catalogued the main problematic experiences reported by Laura and identified the passages that pertained to each clinical problem. The passages were delimited by two judges jointly from transcripts sessions. Raters independently identified the level of assimilation for each passage. Problems that reached at least level 4 in the APES at the end of the process were considered solved (e.g., Detert, Llewelyn, Hardy, Barkham, & Stiles, 2006). We found a single clinical problem that was defined as perfectionism. It comprised 74.5% of her sessions (measured in terms of the proportion of number of words). Laura presented a main maladaptive scheme of perfectionism that provided a sense of failure when she was not able to meet her expectations. This perception of herself was present in many areas of her life, such as body image, occupational performance, and her relationship with her mother. This problem was quite improved across the process. At the beginning of therapy, Laura was not able to clearly formulate her problem, expressing overgeneralized distressing thoughts, revealing an overall perception of herself as incompetent, and psychological pain around her main areas of concern (e.g., eating habits, performance). At the middle of therapy, Laura worked on her cognitive scheme of worthlessness and she began considering other perspectives about her clinical problem. At the end of therapy, Laura already assumed a new understanding of her problem and reality (e. g., I am no better or worse than anyone else, I do not have to be perfect) and showed a positive affective tone. She was capable of a metacognitive position, understanding the change process from the beginning to the end of treatment. The clinical problem was present in all 16 sessions of the therapeutic process. The average level of assimilation ranged from 2.2 (session 1) to 5.4 (session 16), indicating that this clinical problem went from unresolved, at the beginning of therapy, to resolved at the end of therapy.

Analysis of the main clinical problem

Unitizing

The unitizing process involved two steps. Firstly, two judges (a PhD student and a Master’s student in clinical psychology) received training on the unitizing procedure. For that, the judges followed the guidelines described by Hill and O’Brien (1999) until reaching an agreement of above 90% in three training sessions. After a training phase, the pair of judges divided the passages pertaining to perfectionism into units of analysis. These units corresponded to independent grammatical sentences, allowing detect small changes in the client’s speech. For example, in the Laura turn-taking pertaining to perfectionism: I cannot explain why I have such a need to be perfect. Why am I so afraid of the possibility of other people judging or evaluating me?, the judges found two units of analysis: I cannot explain why I have such a need to be perfect and Why am I so afraid of the possibility of other people judging or evaluating me?.

Immersed and distanced speech

Following the unitizing of the passages pertaining to the main clinical problem, each unit of analysis was analyzed with the MIDS to assess the presence of immersed and distanced speech. Initially, the same judges that were involved in the unitizing process underwent intensive training about immersed and distancing speech that consisted of reading relevant articles and manuals, and practicing the coding procedures in a therapeutic case. Should be noted that one of judges (PhD student) was expert in this type of procedure. This phase lasted about three months and was deemed concluded once the judges reached an acceptable Cohen’s kappa (Cohen’s kappa ≥ .75) (Hill & Lambert, 2004).

Then, these judges independently coded each unit of analysis for the presence or absence of five mutually exclusive categories (what statements, attributive, insight statements, closure statements and other statements).

Emotional arousal and valence

Four judges (three PhD students, and one Master’s student in clinical psychology) used the CEAS-III. The CEAS-III assessed the presence of emotional arousal and identified its affective valence, classifying the emotion as positive or negative. The training phase consisted of approximately 40 hours in which videotapes were viewed and discussed until an acceptable agreement (Cohen’s kappa=.75) among four raters was reached (Hill & Lambert, 2004). Then, two teams of two judges were created. Sessions were distributed randomly for each team. The judges watched the video recording of each session in order to identify, by consensus, emotional episodes (EEs) pertaining to perfectionism. The identification of the EEs was carried out in this study in order to detect the segments of psychotherapy where the client experienced an emotion, following the procedures adopted in previous relevant studies regarding the identification of emotional responses or action tendencies. Thus, all EEs within clinical problem was consider, once that the EEs give the moments in which the client expresses an emotion in response to some situation or context (Greenberg & Korman, 1993). The beginning of the EE was defined when an emotion emerged regarding a thematic content. The end of EE was noted as when at least one of the following situations occurred: the emotion identified finished, a new emotional response was expressed, or the thematic content changed (see Greenberg & Korman, 1993). Judges independently classified the emotion contained in each one of the EEs. Finally, these emotions were grouped according to their affective valence (positive or negative). The following segment illustrates an EE pertaining to perfectionism classified with negative valence:

or to say ‘look I really got fat’ I am very ashamed about that and those people who do not see me for some time. I think – I almost panic to find someone, because it really is… because it´s a big difference, if I showed you a picture before and after the difference is huge, twenty kilos of difference, it really is. So ah, this is how I feel, I feel bad, I can’t see myself in the mirror.

The arousal of positive and negative emotions was measured by the relative frequency of units of analysis belonging to each emotional valence.

Reliability

The average reliability calculated by the ICC (Gwet, 2014) for assimilation levels coding process was high, ICC (2,1)=.93. In the unitizing procedures judges reached an agreement above 90%, as recommended by Hill and O’Brien (1999). The global Cohen´s kappa for immersion/ distancing and for emotional arousal coding processes was .83 and .80, respectively, which showed a strong interrater reliability (Gwet, 2014). Disagreements in all measures were solved by consensus (see Hill et al., 2005). The application of each scale (APES, MIDS and CEAS-III) was performed by different judges who were blind to the results obtained with the other scales.

Outcome assessment

The depressive symptoms were assessed by the BDIII in sessions 1, 4, 8, 12 and 16 (sessions where the BDIII was applied in accordance with the assessment protocol of the clinical trial). The clinical symptoms were assessed by OQ-10.2 in all sessions.

Quantitative analysis

Spearman’s rho correlations, computed on the basis of SMA (Borckardt & Nash, 2014), were used to analyze the evolution of immersed and distancing speech in terms of occurrence over time and slope vector (that is, the trend direction), and to analyze the relationship between immersion/ distancing with emotional arousal and general clinical symptoms. SMA was developed to deal with the statistical problems caused by case-based time series studies and it uses a bootstrap sampling method, controlling for autocorrelation. The correlation between immersed/distanced speech and BDI-II was not carried out due to the restricted number of observations with BDI-II.

Results

Immersion and distancing

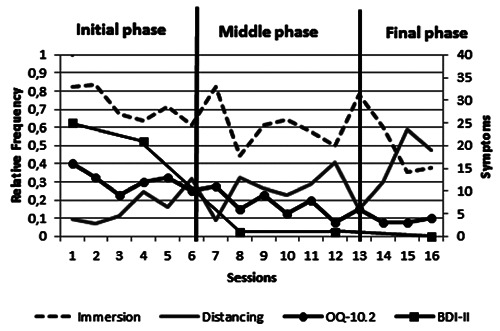

The relative frequency of immersed speech was substantially higher than the relative frequency of distanced speech in all phases, except for the last two sessions (Figure 1 and Table 2). This revealed that immersion was the dominant perspective in the therapeutic process. A significant decrease was observed in immersed speech from the initial to the middle phase, both in terms of relative frequency, rs(11)=-.64, P=.028, and slope vector, rs(11)=-.71, P=.014. From the middle to final phase, there were no significant differences in relative frequency, rs(11)=-.41, P=.179, or in the slope vector, rs(11)=-.44, P=.184, for this type of speech, suggesting stability of immersed speech from the middle phase onwards. Regarding distanced speech, significant increases were observed from the initial phase to the middle phase, both in terms of relative frequency, rs(11)=.58, P=.049, and slope vector, rs(11)=.65, P=.033. From the middle to final phase, there were no significant differences in terms of relative frequency, rs(11)=.46, P=.223, or slope vector, rs(11)=.55, P=.121, for this type of speech, also suggesting stability of distanced speech from the middle phase onwards.

Figure 1.

Relative frequency of immersion and distancing and clinical symptoms throughout therapy.

Table 2.

Relative frequency of type of speech and emotional arousal by phase of treatment.

| Initial phase | Middle phase | Final phase | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Immersed speech | .74 | .07 | .62 | .12 | .52 | .18 | .63 | .15 |

| Distanced speech | .14 | .07 | .25 | .09 | .38 | .17 | .26 | .15 |

| Negative emotions | .37 | .13 | .17 | .11 | .14 | .17 | .22 | .17 |

| Positive emotions | .09 | .09 | .22 | .13 | .28 | .15 | .20 | .15 |

M mean SD standard deviation.

The following passages illustrate the change from an immersed speech to a distanced speech regarding her experience of unemployment. In the first passage (session 3, initial phase) Laura adopted an immersed speech, while in the second passage (session 16, final phase) Laura adopted a distanced speech.

Therapist: What do you think about what others think about this situation?

Laura: I think others think ‘she is unemployed because she is not competent in what she does and therefore she was fired’ or ‘she is unemployed because she has a good life, she is financially sustained by her husband.’ This is what I think. [...]

Therapist: And for this reason you must feel shame, Isn’t it?

Laura: I don’t know, but that’s what I feel. (session 3)

Laura: [...] I felt guilty because I thought I had failed, right? As a person I had failed.

Therapist: Hm-hm.

Laura: I failed because I could not stand the pressure and I got sick [...] and I think maybe the key was to realize that I am like other people. (session 16)

Immersion/distancing and clinical outcome

There was a significant positive relationship between immersed speech and general clinical outcome (OQ-10.2), rs(16)=.75, P=.001. Conversely, a negative relationship was observed between distanced speech and general clinical outcome, rs(16)=- .74, P=.0001. According to Figure 1, depressive symptoms at the beginning of therapy were moderate (BDI-II=25), decreased in the following assessments, and disappeared in the last session (BDI-II=0). General clinical outcome improved across sessions, reaching no clinical relevance at the end of therapy (OQ- 10.2=4). Immersion was still the most prevalent speech when the BDI-II scores were already under the clinical threshold (sessions 8 and 12).

Immersion/distancing and emotional arousal

One hundred and seventy-five EEs were identified, corresponding to 41.5% of the client’s speech. According to Table 2, there was a decrease of negative emotions and an increase of positive emotions across the therapeutic process. A significant positive relationship between immersed speech and negative emotions, rs(16)=.80, P=.0001, and distanced speech and positive emotions, rs(16)= .73, P=.0001, and a significant negative relationship between immersion and positive emotions, rs(16)=- .69, P=.001, and distancing and negative emotions, rs(16)= -.87, P=.0001, were observed.

Discussion

This longitudinal analysis revealed a pattern of immersion and distancing throughout the therapeutic resolution of a clinical problem: immersion decreased and distancing increased, especially from the initial to the middle phase of the therapy. Moreover, in the last two sessions, we witnessed a dominance reversal, in which distancing became more frequent than immersion. We can find links between the cognitive behavior therapy, namely the intervention protocol for depression (Beck et al., 1979), and these results. According to this therapeutic approach, from the beginning of the middle or working phase is common to apply cognitive techniques, which encourage the clients to analyze and adopt new perceptions of the reality, i.e., clients are encouraged to focus less in their initial point of view about experience (firstperson perspective) and seek new alternatives through an observer position of life experiences. For example, specific cognitive techniques to help the client challenge negative automatic thoughts involves distancing of oneself from a belief to allow a more broad and objective analysis of it, typically in cognitive restructuring (DeRubeis et al., 2010), which seems consistent with significant decrease of immersion and increase of distancing. Should be noted that these techniques are closely associated with the metacognitive functioning (Dobson & Dozois, 2010). Specifically, to decenter from thoughts, and thereby view thoughts as events in the mind, allowing to understand one’s own cognitive processes as well as other’s minds, is a metacognitive ability (Segal et al., 2002, 2013). In this sense, distancing may be the one of the steps involved in the metacognitive process. Regarding the dominance of distancing in the last two sessions, it also seems to be in accordance to the intervention CBT protocol for depression (Beck et al., 1979), in which therapists help client to analyze the changes across therapeutic process and to assume an observer position (the client is prompted to assess a past experience from a broad perspective, taking into account past and current experiences).

This pattern of decreasing of immersion and increasing of distancing was related with a decrease to a non-clinical level of symptoms. These results are consistent with experimental studies that consider distancing as an important perspective in reconstruction of the experience (Ayduk & Kross, 2010b; Kross & Ayduk, 2011; Kross et al., 2012) and well-being (e.g., Bruehlman-Senecal; Mischkowski et al., 2012). In addition, we observed a positive relationship between immersion and negative emotions, and between distancing and positive emotions, which is also consistent with the view that immersion on problematic states tends to support negative affect, while more distancing feeds more positive states (e.g., Kross et al., 2014; Kross et al., 2012; Verduyn et al., 2012). Thus, the high immersion and low distancing may be associated with depressive states, emotional distress and unresolved problems in therapy. Some cautions should be taken while considering these results. Our results are basically correlational, and therefore, it is necessary to consider other possible explanations (e.g., the significant increase of distancing may have been a result of the symptomatic change, and not the reversal, or even caused by a third variable).

One important finding in our study was that immersion was dominant in different phases of the resolution of the clinical problem, showing that a high frequency of immersion does not impair the prospects of a good outcome at case level. The dominance of immersion throughout the different phases of the treatment make us suspect that immersed speech is the type of speech requested more often in therapy. Clients need to provide the therapist with context about their personal view on their experience, spending more time in immersion than in distancing. Moreover, we found therapy sessions in which the depressive symptoms were below the clinical threshold, even when immersion was the dominant perspective. In light of this result, the legitimacy of considering immersion as a maladaptive perspective is not completely clear. Immersion and negative emotional arousal can be interpreted as parts of a first step in therapy sessions, especially in the first phase of the process. In our case, this was the developmental pathway of the client: she started by bringing and expressing negative material, in an immersed way, and then progressively became better able to deal with that material in a more distanced and productive way. Therefore, change may be more a feature of the general variation of immersion/distancing (decrease of immersion and increase of distancing across therapy) than of their absolute presence or even dominance. Our observations are also congruent with clinical premises of CBT: initially, the client is expected to retell the problem according to her/his personal perspective, and afterwards, by applying several strategies, such as cognitive restructuring, an observer stance is developed (e.g., Beck, 2011). However, there are some possibilities that should be considered. First, the evolution pattern found in this case may be due to the evolution of the emotional arousal across therapy, i.e., the increase of negative emotions may lead to an immersed reflection on negative experience and the decrease of positive emotions may facilitate a distanced reflection on negative experience. Second, we found immersion as the dominant speech during therapy, with exception of the two last sessions. This result points to the possibility that immersion is the perspective most used by clients in psychotherapy. In this context, clients need to recount their problematic experience, describing thoughts, feelings, behaviors and events, in order to be worked on later. This type of reflection may demand more time in therapy than distancing. Third, the high immersion did not prevent the therapeutic success. Probably, therapy, being a safe and controlled context, facilitates the immersed expression without both rumination and excessive emotional arousal of negative emotions.

Conclusions

Overall, the longitudinal analysis seems to shed some light on the process. The present study emphasizes the importance of more self-reflection regarding the problematic experience, from an observer perspective, towards higher adaptive integration of the experience, higher capacity of emotional regulation, and well-being. This evolution from high immersion at initial phase to more distancing across therapy suggests implications for clinical practice: a regular pattern characterized by constant immersed speech across the therapy may signal that the client is not progressing as desired, and may benefit from techniques that promote distancing. However, the polarized perspective of immersion and distancing seems unable to fully explain the change in clinical problems. Thus, based on the present study, we are proposing that these two processes may be both important in a good outcome. Immersion may also be necessary in the therapeutic process, since it is balanced with distancing moments.

However, we are in need of more empirical studies with larger clinical samples, including contrasting studies with poor outcome cases. We could then observe if different therapies present a similar pattern in terms of immersion and distancing evolution, and if emotional arousal varies according to the type of therapy applied. Although clients with depression may have a similar evolution pattern of immersion and distancing in different types of therapy, probably the time spent in each perspective may be different. For example, it is possible that in solution-focused therapy clients are more encouraged to take a distanced perspective rather than in emotion-focused therapy. In addition, studies on immersion and distancing in the treatment of different disorders are necessary. Do clients with anxiety present the same evolution pattern of immersion and distancing as clients with depression? People with anxiety tend to avoid contact with some experiences. It is possible that these clients take a distanced perspective as an avoidance mechanism, which probably would require immersion as a first step in psychotherapy.

Furthermore, there are some issues that should be studied. For CBT (e.g., Beck, 2011) and literature on the role of cognitive reappraisal in emotional regulation (Duckworth, Gendler, & Gross, 2016; Gross, 2015), change in psychological well-being is associated with change in how the client thinks and responds to the experience, rather than an increase in distancing alone. Finally, it would also be important to test the influence of the therapist in the client’s speech.

References

- Ayduk Ö. Kross E., (2010a). Analyzing negative experiences without ruminating: The role of self-distancing in enabling adaptive self-reflection. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 841-854. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00301.x [Google Scholar]

- Ayduk Ö. Kross E., (2010b). From a distance: implications of spontaneous self-distancing for adaptive self-reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 809-829. doi:10.1037/a0019205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basto I. Pinheiro P. Stiles W.B. Rijo D. Salgado J., (2016). Changes in symptoms intensity and emotion valence during the process of assimilation of problematic experience: A quantitative study of a case of cognitive-behaviorral therapy. Psychotherapy Research. doi:10.1080/10503307.2015.1119325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Rush J.A., Shaw B.F., Emery G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T. Steer R. A. Brown G. K., (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Beck J.S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basic and beyond (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borckardt J. Nash M., (2014). Simulation modelling analysis for small sets of single-subject data collected over time. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24, 492-506. doi:10.1080/09602011.2014.895390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehlman-Senecal E. Ayduk Ö. John O. John O.P., (2016). Taking the long view: Implications of individual differences in temporal distancing for affect, stress reactivity, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. doi:10.1037/pspp0000103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Decker D.L. (2015). Psychological distancing: The effects of narrative perspectives and levels of access to a victim’s inner world on victim blame and helping intention. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 20, 12-24. doi:10.1002/nvsm.1514 [Google Scholar]

- Caro Gabalda I. Stiles W., (2009). Retrocessos no contexto da terapia linguistica de avaliacao [Setbacks in the context of linguistic therapy of evaluation]. Análise Psicológica, 27, 199-212. doi: 10.14417/ap.205 [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D.V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6, 284-290. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho R. Martins A. Barros H., (2002). Clinical profiles relating gender and depressive symptoms among adolescents ascertained by the Beck Depression Inventory-II. European Psychiatry, 17, 222-226. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338 (02)00663-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer J.S. Kendall P.C., (2013). Methodology, design, and evaluation in psychotherapy research. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed., pp. 21-48). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Detert N.B. Llewelyn S. Hardy G.E Barkham M. Stiles W.B., (2006). Assimilation in good- and poor-outcome cases of very brief psychotherapy for mild depression: An initial comparison. Psychotherapy Research, 16, 393-407. doi: 10.1080/10503300500294728 [Google Scholar]

- DeRubeis R.J. Webb C.A. Tang T.Z. Beck A.T., (2010). Cognitive therapy. In K. S. Dobson (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive- behavioral therapies (3rd ed., pp. 277-316). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson K.S. Dozois D.J., (2010). Historical and philosophical bases of the cognitive behavioral therapies. In K.S. Dobson (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies (3rd ed., pp. 3-38). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth A.L. Gendler T.S. Gross J.J., (2016). Situational strategies for self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 35-55. doi:10.1177/1745691615623247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R. Greenberg L.S. Watson J. Timulak L. Freire E., (2013). Research on humanistic-experiential psychotherapies. In M. Lambert, Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp 495-538). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R. Watson J. Goldman R. Greenberg L.S., (2004). Learning emotion focused therapy: The Process-Experiential Approach to Change. Washington, D.C.: America Psychology Association. [Google Scholar]

- First M.B., Gibbon M., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W., Benjamin L.S. (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). (J. Pinto-Gouveia, A. Matos, D. Rijo, P Castilho, & M. Salvador, Trans.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- First M.B. Spitzer R.L Gibbon M. Williams J.B.W., (2002). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version (SCID-I-RV). (A. Costa Maia, Trans.). New York: Biometrics Research. [Google Scholar]

- Foa E.B. Kozak M.J., (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 20-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E.B. Zoellner L.A. Feeny N.C. Hembree E.A. Alvarez-Conrad J., (2002). Does imaginal exposure exacerbate PTSD symptoms? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1022-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosha D. (2000). The transforming power of affect: A model of accelerated change. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L. (2002). Emotion-focused therapy: coaching clients to work through their feelings. Washington: America Psychology Association. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L. (2010). Emotion-focused therapy: theory, research, and practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L.S. Korman L., (1993). Assimilating emotion into psychotherapy integration. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 3, 249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L.S. Rice L.N. Elliott R.K., (1993). Facilitating emotional change: The moment-by moment process. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L.S. Safran J.D., (1987). Emotion in psychotherapy: Affect, cognition, and the process of change. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L.S. Watson J., (2006). Emotion-focused therapy for depression. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Gross J.J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26, 1-26. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781 [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann I. Kross E., (2014). Exploring solomon’s paradox self-distancing eliminates the self-other asymmetry in wise reasoning about close relationships in younger and older adults. Psychological Science, 25, 1571-1580. doi:10.1177/0956797614535400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwet K.L. (2014). Handbook of inter-rater reliability: The definitive guide to measuring the extent of agreement among raters (4th Ed.), Gaithersburg, MD: Advanced Analytics, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C. Wilson K.G. Gifford E.V. Follette V.M. Strosahl K., (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1152-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C.E. Knox S. Thompson B.J. Williams E.N. Hess S.A. Ladany N., (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 196-205. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196 [Google Scholar]

- Hill C.E. Lambert M.J., (2004). Methodological issues in studying psychotherapy processes and outcomes. In M.J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed., pp. 84-136). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hill C.E. O’Brien K.M., (1999). Helping skills: facilitating exploration, insight and action. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox L.H. Foa E.B. Morral A.R., (1998). Influence of emotional engagement and habituation on exposure therapy for PTSD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 185-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan T.B., Barrios V., Forsyth J.P., Steger M.F. (2006). Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: Comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy 44, 1301-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy-Moore E. Watson J., (2001). How and when does emotional expression help? Review of General Psychology, 5, 187-212. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.5.3.187 [Google Scholar]

- Kross E. Ayduk O., (2011). Making meaning out of negative experiences by self-distancing. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 187-191. doi:10.1177/ 0963721 411408883 [Google Scholar]

- Kross E. Bruehlman-Senecal E. Park J. Burson A. Dougherty A. Shablack H. Bremner R. Moser J. Ayduk O., (2014). Self-talk as a regulatory mechanism: How you do it matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106, 304-324. doi:10.1037/a0035173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kross E. Gard D. Deldin P. Clifton J. Ayduk O., (2012). “Asking why” from a distance: Its cognitive and emotional consequences for people with major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 559-569. doi:10.1037/a0028808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M.J. Finch A.M. Okiishi J. Burlingame G.M., (2005). OQ-10.2 Manual. American Professional Credentialing Services, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M.J. Finch A.M. Okiishi J.C. Burlingame G.M. McKelvey C. Reisinger C. W., (1998). Administration and scoring manual for the OQ-10.2: An adult outcome questionnaire for screening individuals and population outcome monitoring. American Professional Credentialing Services LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Mischkowski D. Kross E. Bushman B. J., (2012). Flies on the wall are less aggressive: Self-distancing “in the heat of the moment” reduces aggressive thoughts, angry feelings and aggressive behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 1187-1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.03.012 [Google Scholar]

- Nigro G. Neisser U., (1983). Point of view in personal memories. Cognitive Psychology, 15, 467-482. doi: 10.1016/ 0010-0285(83)90016-6 [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A. Greenberg L. S., (2007). Emotional processing in experiential therapy: Why “the only way out is through”. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 875-887. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman S. (1980). Emotional processing. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 18, 51-60. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(80) 90069-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoilov A. Goldfried M.R., (2000). Role of emotion in cognitive-behavior therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7, 373-385. doi:10.1093/clipsy.7.4.373 [Google Scholar]

- Seelert K.R. (1997). Validation of a brief measure of distress in a primary care setting. University of Utah, Salt Lake City. [Google Scholar]

- Segal Z.V. Williams J.M.G. Teasdale J.D., (2002). Mindfulness- based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Segal Z.V. Williams J.M.G. Teasdale J.D., (2013). Mindfulness- based cognitive therapy for depression (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd K.A., Coifman K.G., Matt L.M., Fresco D.M. (2016). Development of a self-distancing task and initial validation of responses. Psychological Assessment, 28, 841-855. doi:10.1037/pas0000297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J.M. (1998). Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 175-184. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduyn P. Mechelen I.V. Kross E. Chezzi C. Bever F.V., (2012). The relationship cetween self-distancing and the duration of negative and positive emotional experiences in daily life. Emotion, 12, 1248-1263. doi:10.1037/a0028289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Lin Y. Huang C. Yeh K., (2012). Benefitting from a different perspective: The effect of a complementary matching of psychological distance and habitual perspective on emotion regulation, Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 15, 198-207. doi:1 0.1111/j.1467-39X.2012.01372.x [Google Scholar]

- Warwar S.H. Greenberg L.S., (1999). Client Emotional Arousal Scale–III. Unpublished manuscript, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- White R.E., Kross E., Duckworth A.L. (2015). Spontaneous self-distancing and adaptive self-reflection across adolescence. Child Development, 86, 1272-128. doi:10.1111/ cdev.12370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T.D. Gilbert D.T., (2008). Explaining away a model of affective adaptation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 370-386. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00085.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]