Figure 1.

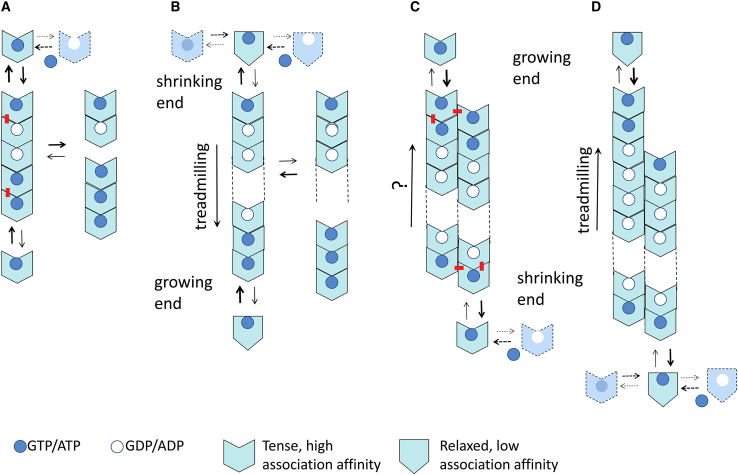

(Model A) Linear isodesmic protein self-association with nucleotide hydrolysis. The nucleotide γ-phosphate at the association interface provides a chemical signal increasing the affinity of subunit addition. Hydrolysis stochastically takes place after the formation of each association contact at an intrinsic average rate, inducing subunit dissociation; nucleotide triphosphate (in excess) is assumed to replace nucleotide diphosphate in monomers and at the exposed subunit at the top. The pentamer in the model represents the product of adding one subunit at each end of a trimer. The newly formed top and bottom interfaces are marked with a red dash. Notice that the penultimate subunit at the top is GDP bound when releasing the top subunit but becomes GTP bound when exposed. (Model B) Linear nucleated polymerization with nucleotide hydrolysis and treadmilling is shown. The protein monomers switch between a state with low self-association affinity when unassembled (relaxed; R) and a state with high-association affinity (tense; T) that forms tight interfaces in the filament. This is the mechanism thought to work for FtsZ. (Model C) Multistranded condensation polymerization with nucleotide hydrolysis (no switch) is shown. In the double-stranded filament exemplified by the model it can be appreciated how filament elongation involves longitudinal and lateral contacts, stabilizing the filament against fragmentation, whereas formation of a hypothetical dimer nucleus involves one type of contact only. (Model D) Multistranded condensation polymerization with nucleotide hydrolysis and assembly switch in combination of Models B and C is shown. This type of mechanism may apply to microtubule and actin assembly. To see this figure in color, go online.