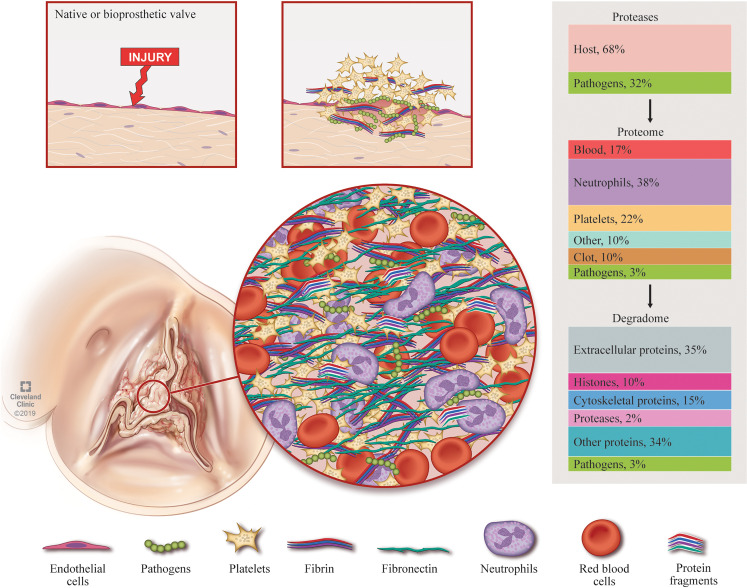

Figure 7. The vegetation proteome and its origins.

Native or bioprosthetic valves are infiltrated directly following bacteremia, or valvular damage, exposing prothrombogenic components to create a platelet-rich nidus. The vegetation grows via layering of components starting with opsonization of pathogens by circulating immunoglobins, complement, and other factors of the innate immune system in response to pathogen virulence factors. Circulating fibrin and fibronectin trap red blood cells and recruit additional platelets as they bind to the nidus. The accumulated platelets provoke additional fibrin deposition in the region. Neutrophils invade the site of infection. Inaccessible pathogens within the valve mediate persistent neutrophil chemotaxis via degranulation and NETosis, releasing citrullinated DNA and proteases. NETosis and platelet degranulation further stimulates cellular and protein deposition. Vegetations are thus a conglomerate of multiple proteomes whose respective percentage contributions can vary widely between vegetations. Pathogen and host protease-mediated vegetation turnover may destabilize the vegetation, which, when combined with turbulent valve function, could promote embolization, leading to cerebral or peripheral abscesses, infarcts, and mycotic aneurysms. Human as well as microbial proteases can contribute to protein turnover in vegetations. TAILS analysis suggested extensive turnover of extracellular proteins, with fibrin and fibronectin among the top proteins modified by proteolysis.