Abstract

Purpose:

The cornea is the most significant refractive medium in the eye. Pathologies affecting the cornea usually have a great impact on vision. The etiology of corneal disorder varies from one geographical location to another. The objective of this study was to determine the pattern of corneal disorders at Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective study of case records of patients with cornea disorders over a 5-year period was carried out. Demographic characteristics, presenting visual acuity, and risk factor for cornea disorders were retrieved. Data were entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20, and statistical significance was inferred at P < 0.05.

Results:

Corneal disorders accounted for 3.3% of the eye disorders seen during the period of study. The median age was 37 years. Males outnumbered females giving a ratio of 1.9:1 and the age range from 0.25 to 92 years. There were more females than males in the 11–20 years’ age group. Students (84, 25.4%) and artisans (62, 18.8%) were the two leading occupational groups. Infectious cases constituted 27.2% of the cases. Visual acuity at presentation was <3/60 in 131 (39.7%) cases. Foreign body entry was the leading etiologic agent in 101 (30.6%) cases.

Conclusion:

Half of the patients were blind at presentation, and many of them presented after more than 1 week of the onset of symptoms. Corneal foreign body, trauma, and vernal keratoconjunctivitis were the leading known predisposing factors. There will be need to emphasize more on the role of protective eye devices among our people, especially those who engage in outdoor activities.

Keywords: Blindness, cornea, disorder, tertiary, cécité, cornée, trouble, tertiaire

Résumé

Objectif:

La cornée est le milieu de réfraction le plus important de l’oeil. Les pathologies affectant la cornée ont généralement un grand impact sur la vision. L’étiologie du trouble cornéen varie d’un emplacement géographique à un autre. L’objectif de cette étude était de déterminer le schéma des troubles de la cornée à l’hôpital universitaire d’Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti.

Matériel et méthodes:

Une étude rétrospective des dossiers des patients atteints de troubles de la cornée sur une période de 5 ans a été réalisée. Les caractéristiques démographiques, présentant l’acuité visuelle et le facteur de risque de troubles de la cornée ont été récupérées. Les données ont été entrées dans le progiciel statistique pour la version 20 des sciences sociales, et la signification statistique a été déduite à P <0,05.

Résultats:

Les troubles cornéens représentaient 3,3% des troubles oculaires observés pendant la période d’étude. L’âge médian était de 37 ans. Les hommes étaient plus nombreux que les femmes, ce qui.

INTRODUCTION

The cornea is the most significant refractive medium in the eye. It accounts for approximately two-thirds of the refractive power of the eye.[1] Pathologies affecting the cornea, therefore, usually have a great impact on vision, especially when it involves the central cornea. Corneal disorders constitute a leading cause of visual impairment and blindness worldwide.[2] The pattern, causes, and predisposing factors to corneal diseases vary globally and from region to region within the same country.[3,4] Disorders of the cornea can be broadly classified into congenital and acquired. Studies have implicated infectious and noninfectious causes in the pathogenesis of corneal disorders in different parts of the world. Infectious cases can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoans, or parasites.[5,6] Noninfectious cases can be due to congenital disorders, corneal dystrophies, and degenerations. Bacterial keratitis accounts for the greatest number of infectious cases worldwide. Fungal keratitis has been reported to occur more in the developing nations due to the increased risk of agriculturally related trauma from vegetative matters.[7] The pattern of corneal disorders in Ekiti has not been studied. There are only a few specific reports of cases due to chemical injury and harmful traditional eye medications.[8,9] The reports of this study will assist in planning an improved eye care delivery for our patients and also provide relevant statistics for health education for the general public.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital (EKSUTH) offers tertiary eye care service delivery to patients with eye complaints through the eye clinic. Patients in the clinic come from Ekiti state and its neighboring states of Ondo, Osun, and Kogi. The clinic runs on outpatient basis 4 days every week, whereas emergency cases are seen every day including weekends. All case records of patients with the diagnosis of any corneal pathology between January 2014 and December 2018 were retrieved from the clinic register and record unit of the department. Information retrieved from the case records include demographic characteristics, place of residence, presenting visual acuity, social habits such as cigarette smoking and alcohol intake, duration between onset of symptom and presentation at the clinic, final diagnosis, and predisposing factors. Individuals with visual acuity <3/60 in the better eye were regarded as blind, whereas those with visual acuity of <6/18 up to 3/60 in the better eye were considered visually impaired. Data obtained were entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20 (Armonk NY: IBM Corp). Data analysis was carried out for continuous and noncontinuous variables. Statistical significance was inferred when P < 0.05 was obtained. Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the EKSUTH hospital.

RESULTS

We evaluated the records of 330 patients with the diagnosis of varying forms of corneal disorders during the period of study. This accounted for 3.3% of the total 9950 new patients seen. Males constituted 212 (64.2%), whereas the other 118 (35.8%) were female. This gives a male: female ratio of 1.9:1. The ages of the patients ranged from 0.25 to 92 years, with a median of 37 years. Children <16 years accounted for 65 (19.7%), whereas those aged above 16 years constituted 265 (80.3%).

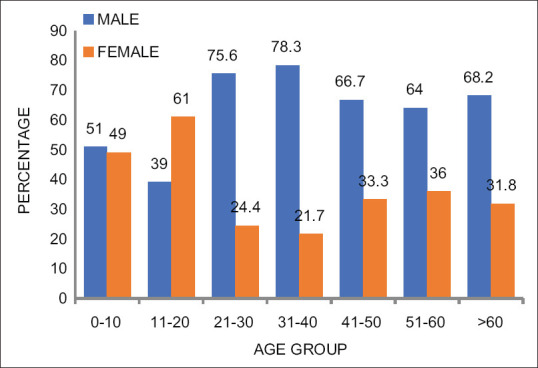

The peak age of presentation was 31–40 years of age among males and 11–20 years in females. Males outnumbered the females across all age groups except in the 11–20 years’ age group [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Age and sex distribution of patients with cornea disease

The risk of female preponderance before the age of 16 years was 2.013 (confidence interval: 1.535–2.640) P < 0.001.

Students constituted 25.4% of the study group. Other occupational distributions are as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and sex of patients with cornea pathology

| Male, n (%) | Female, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||

| <16 | 26 (7.9) | 39 (11.8) | 65 (19.7) |

| >16 | 186 (56.4) | 79 (23.9) | 265 (80.3) |

| Occupation | |||

| Student | 41 (12.4) | 43 (13.0) | 84 (25.4) |

| Artisan | 57 (17.3) | 5 (1.5) | 62 (18.8) |

| Trader | 21 (6.4) | 40 (12.1) | 61 (18.5) |

| Farmer | 47 (14.2) | 6 (1.8) | 53 (16.0) |

| Civil servant | 47 (14.2) | 6 (1.8) | 53 (16.0) |

| Dependent | 5 (1.5) | 8 (2.4) | 13 (3.9) |

| Others | 0 | 4 (1.2) | 4 (1.2) |

There were 90 (27.2%) cases due to infectious causes and 240 (72.8%) noninfectious cases in the ratio 1:2.7.

Table 2 shows that 131 (39.7%) presented with visual acuity of <3/60 at presentation. Those due to microbial keratitis were 45 (34.4%), whereas 86 (65.6%) were as a result of noninfectious causes. Hypopyon was present in 15 (4.5%).

Table 2.

Etiological agents, corneal pathology, and presenting visual acuity

| Etiologic agent | Blindness, n (%) | Not blind, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious keratitis | |||

| Bacteria | 39 (43.3) | 34 (37.8) | 73 (81.1) |

| Viral | 4 (4.4) | 8 (8.9) | 12 (13.3) |

| Fungal | 2 (2.2) | 3 (3.3) | 5 (5.6) |

| Noninfectious | |||

| Corneal foreign body | 3 (1.3) | 74 (30.8) | 77 (32.1) |

| Corneal opacity | 36 (15) | 19 (7.9) | 55 (22.9) |

| Ulcerative keratitis | 13 (5.4) | 36 (15) | 49 (20.4) |

| Corneal erosion/abrasion | 1 (0.4) | 22 (9.2) | 23 (9.6) |

| Bullous keratopathy | 17 (7.1) | 0 | 17 (7.1) |

| Open-globe injury | 13 (5.4) | 3 (1.3) | 16 (6.7) |

| Anterior staphyloma | 3 (1.3) | 0 | 3 (1.3) |

| Total | 131 (39.7) | 199 (60.3) | 330 (100) |

Mild-to-moderate visual impairment was observed in 62 (18.7%) patients [Table 3].

Table 3.

Presenting visual acuity of patients with cornea pathology

| Visual acuity | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 6/4-6/18 | 125 (37.9) |

| 6/24-6/60 | 47 (14.2) |

| 5/6-3/60 | 15 (4.5) |

| <3/60 | 131 (39.7) |

| BNBL | 12 (3.6) |

| Total | 330 (100.0) |

BNBL=Believed not blind

The duration between onset of symptoms and presentation ranged from <24 h to up to 22 years. About 208 (73.8%) presented within 6 weeks of the onset of symptoms, whereas 74 (26.2%) presented more than 6 weeks after the onset of symptoms. A positive history of alcohol intake was obtained in 58 (18.6%), whereas cigarette smoking was obtained in 14 (4.5%).

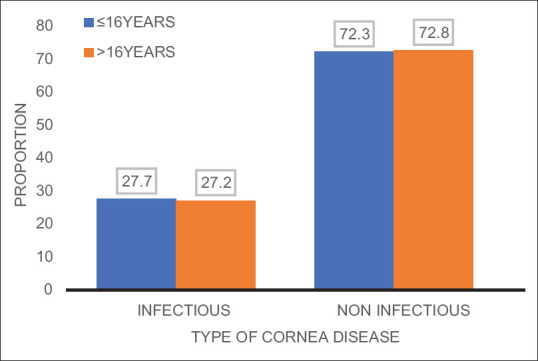

The place of residence was within the state capital in 146 (44.2%) and outside the state capital in 166 (50.3%). Of the infectious cases, 27.7% were children, whereas 27.2% were adults.

In 40.6% of the patients, the predisposing factor to corneal disorder could not be ascertained. Presentation to the eye care center was within 1 week of the onset of symptoms in 130 (45.9%), >1–4 weeks in 78 (27.6%), >1–6 months in 34 (10.3%), and >6/12 in 41 (14.5%).

DISCUSSION

Corneal disorders accounted for 3.3% of the total number of new patients seen in our center. The higher ratio of males in this study is similar to findings from some other studies within[3,10,11,12] and outside our country.[13,14] This has been opined to be due to greater exposure of males to activities that make them prone to risk.[15] It was, however, observed that there was a female preponderance among those aged <16 years of age (39, 11.8%) with a statistically significant higher risk among females in this age group. This agrees with the finding in Ife[16] and Ibadan[17] both in Southwest Nigeria. This observation was said to be a result of greater tendency of young females to report visual problems more than males. It differs, however, from reports from some other studies where male preponderance has been reported[18,19,20] and a few others where similar prevalence exists in both.[20] The lower age limit in this study is much lower compared to a report from Eastern[3] and North-Central Nigeria.[12] This was a case of bilateral microbial keratitis, and the exact predisposing factor could not be determined. The upper age limit was a 92-year-old man with corneal opacity due to old microbial keratitis. Children accounted for close to 20% of all the patients with corneal disorders. This is quite worrisome because of the associated risk of childhood blindness, the higher blind years in children, as well as the enormous impact this could have on the future of any community. Childhood blindness is second only to cataract blindness in terms of blind years.[21] Infectious disorders accounted for 27.7% of corneal disorders among children [Figure 2]. This is higher than other studies done in some other regions in the southwest.[17] The involvement of children in agricultural activities in rural communities may pose a risk for increase in infectious keratitis among this age group.[16] More so, the involvement of children in unsupervised play has also been reported to increase the risk of trauma in this age group.[16,22]

Figure 2.

Etiological type of cornea disease and age group

Students, traders, and farmers accounted for more than half of the occupational groups among our patients [Table 1]. This is similar to finding in Ilorin, Nigeria.[12] The engagement of these groups in outdoor activities could be a possible explanation for this.[3]

More than one-third of the patients (131, 39.7%) presented with blindness, whereas 4.5% presented with severe visual impairment [Table 3]. This underscores the contribution of the cornea to vision, especially when cornea disorders involve the central portion of the cornea. Poor vision has been found to be one of the leading eye complaints among patients with corneal disorders.[1,3,4,12]

Infectious cases otherwise referred to as microbial keratitis accounted for 27.3% of all the cases. These groups of disorders have been found to be potentially blinding with risk of severe visual loss, especially when there is a delay in treatment. The prevalence of this condition varies across geographical locations depending on the type and causative factors.[4,23] In this study, bacterial keratitis accounted for majority (81.1%) of infectious cases, whereas fungal keratitis was found in 5 (5.6%) cases. This is similar to the report from Olawoye et al. in Ibadan.[4] Fungal keratitis has been reported to be more common in the developing nations because of the greater involvement in agricultural works posing increased exposure to vegetative matter.[7,14,23] The occupational distribution of our patients with high number of students and civil servants could account for the low prevalence of fungal keratitis in this study. Bacterial keratitis has been reported to be the most common form of microbial keratitis in the developed nations of the world.[24,25] There was no case of contact lens-related keratitis among our patients. This is because the use of contact lens is not common in our environment just like in some other regions of the country.[3,4,26,27] Contact lens-related keratitis is common in the developed nations of the world.[28,29]

Some patients presented with superficial corneal foreign body [32.1% Table 3]. Some of these occurred during routine day-to-day activities, especially among the traders and artisans, whereas some patients could not identify the activity preceding the onset of their symptoms. All had foreign body removal with prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics. Many corneal ulcers are secondary to noninfectious processes.[3] This was the case in 20.4% of our patients [Table 3]. All these were managed with prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics. Bullous keratopathy secondary to cataract surgery and complicated cataract were seen in 17 (7.1%). It is important that all patients undergoing cataract surgery should have adequate protection of the corneal endothelium with generous viscoelastic agents in order to minimize the occurrence of this possible complication.

Hypopyon was present in only 4.5% of the cases. The presence of hypopyon signifies activities in the anterior chamber and may not be specific for fungal or bacterial keratitis. This is lower than findings from reports in some other studies.[12,30]

Some of the identified predisposing factors to corneal pathology include foreign body entry (30.6%), trauma (13%), and allergic conjunctivitis [Table 4]. This is similar to findings in some other studies.[4,5,12,23,31] Ocular allergy, particularly vernal keratoconjunctivitis, has the potential to cause corneal erosions which can predispose to microbial keratitis.[4] Corneal opacity can also occur from poorly managed or neglected severe cases of ocular allergy. Communities with largely agrarian labor and a dusty environment have been identified as risk factors for allergic conjunctivitis, especially among children.[16] Children and adults were almost equally affected by both infectious and noninfectious causes [Figure 2].

Table 4.

Predisposing factors to cornea disease

| Factors | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Unknown | 134 (40.6) |

| Foreign body entry | 101 (30.6) |

| Trauma | 43 (13.0) |

| Allergy (vernal keratoconjunctivitis) | 26 (7.9) |

| Lens related (cataract surgery/complicated cataract) | 19 (5.8) |

| Others (glaucoma, trichiasis, lagophthalmos, and measles) | 7 (2.1) |

| Total | 330 (100) |

This study revealed that nearly half (45.9%) of the patients presented within 1 week of the onset of symptoms. This shows delayed presentation in our environment similar to reports from other studies.[12] Some of these patients had used diverse self-medication measures before presentation. This might explain a high percentage of blind patients at presentation. Corneal disorders, especially microbial keratitis, are potentially blinding except prompt and appropriate interventional measures are instituted.[4]

CONCLUSION

Corneal disorders are common in our environment. About half of the patients were blind at presentation and many of them presented after more than 1 week of the onset of symptoms. All age groups were affected. Corneal foreign body, trauma, and vernal keratoconjunctivitis were the leading known predisposing factors. There will be need to emphasize more on the role of protective eye devices among our people, especially those who engage in outdoor activities. Furthermore, the importance of early presentation to the eye care facility needs to be emphasized in our community.

Limitation of the study

Some patient notes were missing from the records.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We wish to acknowledge Mr. Adeosun Temidayo who assisted with the retrieval of the records of the patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mashige KP. A review of corneal diameter, curvature and thickness values and influencing factors. Afr Vision Eye Health. 2013;72:185–94. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitcher JP, Srinivasan M, Upadhyay MP. Corneal blindness: A global perspective. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:214–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oladigbolu K, Rafindadi A, Abah E, Samaila E. Corneal ulcers in a tertiary hospital in Northern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2013;12:165–70. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.117626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olawoye OO, Bekibele CO, Ashaye AO. Suppurative keratitis in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Nigerian J Ophthalmol. 2011;19:27–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong RL, Gangwani RA, Yu LW, Lai JS. New treatments for bacterial keratitis. J Ophthalmol. 2012;2012:831502. doi: 10.1155/2012/831502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao J, Yang Y, Yang W, Wu R, Xiao X, Yuan J, et al. Prevalence of infectious keratitis in Central China. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas PA, Kaliamurthy J. Mycotic keratitis: Epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:210–20. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayanniyi AA. A 39-year-old man with blindness following the application of raw cassava extract to the eyes. Digit J Ophthalmol. 2009;15:27–9. doi: 10.5693/djo.03.2009.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajite KO, Fadamiro OC. Prevalence of harmful/traditional medication use in traumatic eye injury. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:55–9. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n4p55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashaye AO, Oluleye TS. Pattern of corneal opacity in Ibadan, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2004;3:185–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezegwui IR. Corneal ulcers in a tertiary hospital in Africa. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:644–6. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saka SE, Ademola-Popoola DS, Mahmoud AO, Fadeyi A. Presentation and Outcome of Microbial Keratitis in Ilorin. Nigeria J Adv Med Med Res. 2015;6:795–803. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basak SK, Basak S, Mohanta A, Bhowmick A. Epidemiological and microbiological diagnosis of suppurative keratitis in Gangetic West Bengal, eastern India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2005;53:17–22. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.15280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leck AK, Thomas PA, Hagan M, Kaliamurthy J, Ackuaku E, John M, et al. Aetiology of suppurative corneal ulcers in Ghana and south India, and epidemiology of fungal keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1211–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.11.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Négrel AD, Thylefors B. The global impact of eye injuries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1998;5:143–69. doi: 10.1076/opep.5.3.143.8364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onakpoya OH, Adeoye AO. Childhood eye diseases in southwestern Nigeria: A tertiary hospital study. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64:947–52. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009001000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ajaiyeoba AI, Isawumi MA, Adeoye AO, Oluleye TS. Prevalence and causes of eye diseases amongst students in South-Western Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2006;5:197–203. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salman MS. Pediatric eye diseases among children attending outpatient eye department of Tikrit Teaching Hospital. Tikrit J Pharm Sci. 2010;7:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashaye AO. Eye injuries in children and adolescents: A report of 205 cases. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:51–6. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30812-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehari ZA. Pattern of childhood ocular morbidity in rural eye hospital, Central Ethiopia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dandona L, Gilbert CE, Rahi JS, Rao GN. Planning to reduce childhood blindness in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1998;46:117–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayanniyi AA, Mahmoud OA, Olatunji FO, Ayanniyi RO. Pattern of ocular trauma among primary school pupils in Ilorin, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2009;38:193–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ezisi CN, Ogbonnaya CE, Okoye O, Ezeanosike E, Ginger-Eke H, Arinze OC. Microbial keratitis – A review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, ocular manifestations, and management. Nigerian J Ophthalmol. 2018;26:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estopinal CB, Ewald MD. Geographic disparities in the etiology of bacterial and fungal keratitis in the United States of America. Semin Ophthalmol. 2016;31:345–52. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2016.1154173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suwal S, Bhandari D, Thapa P, Shrestha MK, Amatya J. Microbiological profile of corneal ulcer cases diagnosed in a tertiary care ophthalmological institute in Nepal. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16:209. doi: 10.1186/s12886-016-0388-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dawodu OA, Osahon AI, Emifoniye E. Prevalence and causes of blindness in Otibhor Okhae teaching hospital, Irrua, Edo State, Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2003;10:323–30. doi: 10.1076/opep.10.5.323.17325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nwosu SN, Onyekwe LO. Corneal ulcers at a Nigerian eye hospital. Nigerian J Surg Res. 2003;5:152–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preechawat P, Ratananikom U, Lerdvitayasakul R, Kunavisarut S. Contact lens-related microbial keratitis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:737–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mah-Sadorra JH, Yavuz SG, Najjar DM, Laibson PR, Rapuano CJ, Cohen EJ. Trends in contact lens-related corneal ulcers. Cornea. 2005;24:51–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000138839.29823.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bharathi MJ, Ramakrishnan R, Meenakshi R, Shivakumar C, Raj DL. Analysis of the risk factors predisposing to fungal, bacterial and Acanthamoeba keratitis in South India. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:749–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bharathi MJ, Ramakrishnan R, Vasu S, Meenakshi R, Shivkumar C, Palaniappan R. Epidemiology of bacterial keratitis in a referral centre in south India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2003;21:239–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]