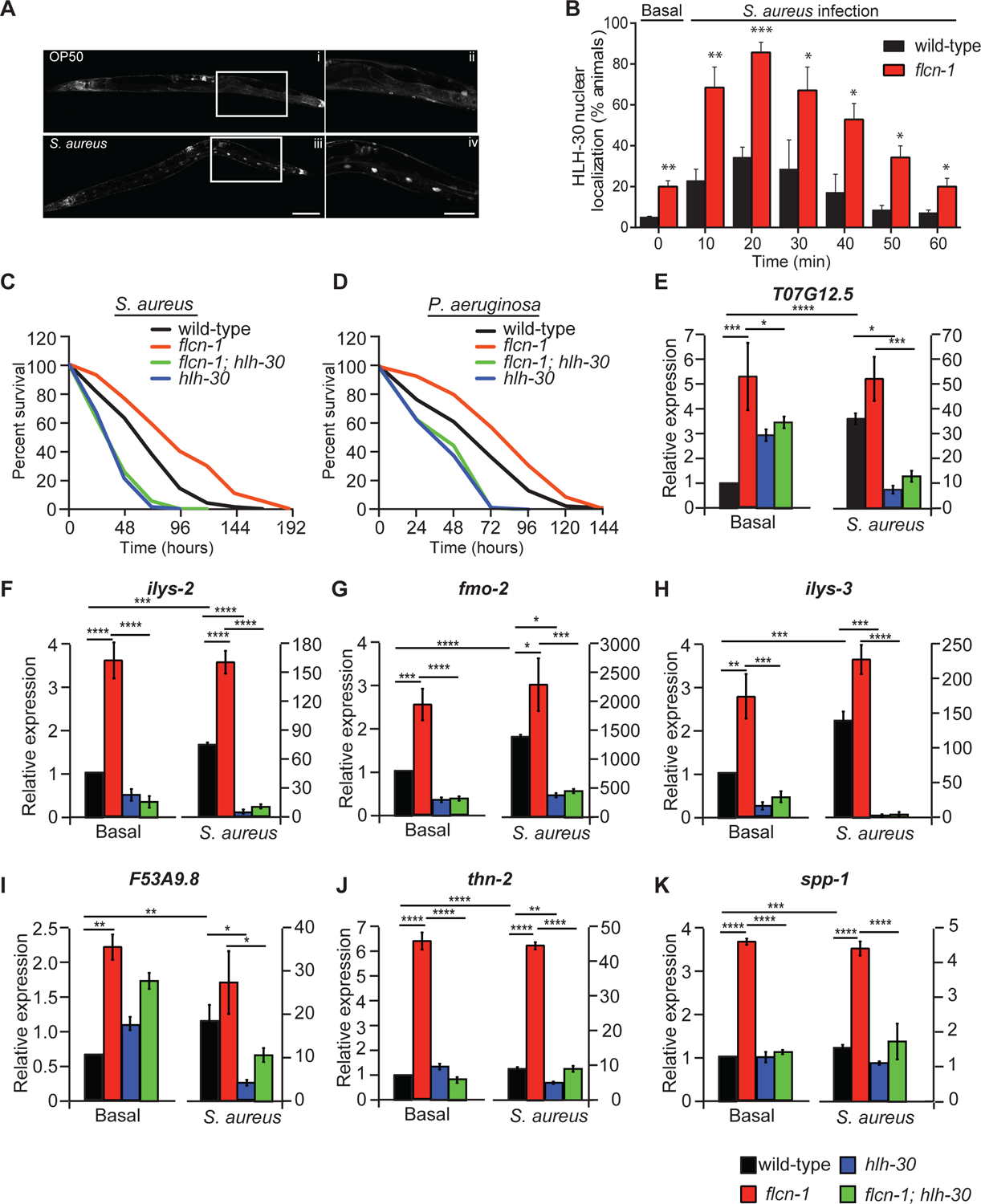

Figure 2: Loss of flcn-1 increases pathogen resistance via HLH-30 activation.

(A) Representative micrographs of HLH-30::GFP at basal level or after infection with S. aureus for 30 min. The signal is found in the nuclei of enterocytes, a cell-type in which lipids are stored in nematodes. Scale bars in i, iii and in ii, iv represent 100 μm and 50 μm respectively. (B) Percent animals showing HLH-30 nuclear translocation in hlh-30p::hlh-30::GFP and flcn-1; hlh-30p::hlh-30::GFP worm strains upon S. aureus infection for indicated time points to determine HLH-30 nuclear localization upon flcn-1 loss at basal level (time 0) and upon S. aureus infection. Data represents the mean ± SEM from three independent repeats, n ≥ 30 animals/condition for every repeat. Significance was determined using student’s t-test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). (C, D) Percent survival of indicated worm strains upon infection with S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. Refer to Table S1 for details on number of animals utilized and number of repeats. Statistics obtained using Mantel-Cox analysis on the pooled curve. (E-K) Relative mRNA expression of indicated target genes in wild-type, flcn-1(ok975), flcn-1(ok975); hlh-30 (tm1978), and hlh-30 (tm1978) animals at basal level and after treatment with S. aureus for 4 h. Data represents the average of three independent experiments done in triplicates ± SEM. Significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with the application of Bonferroni correction (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).