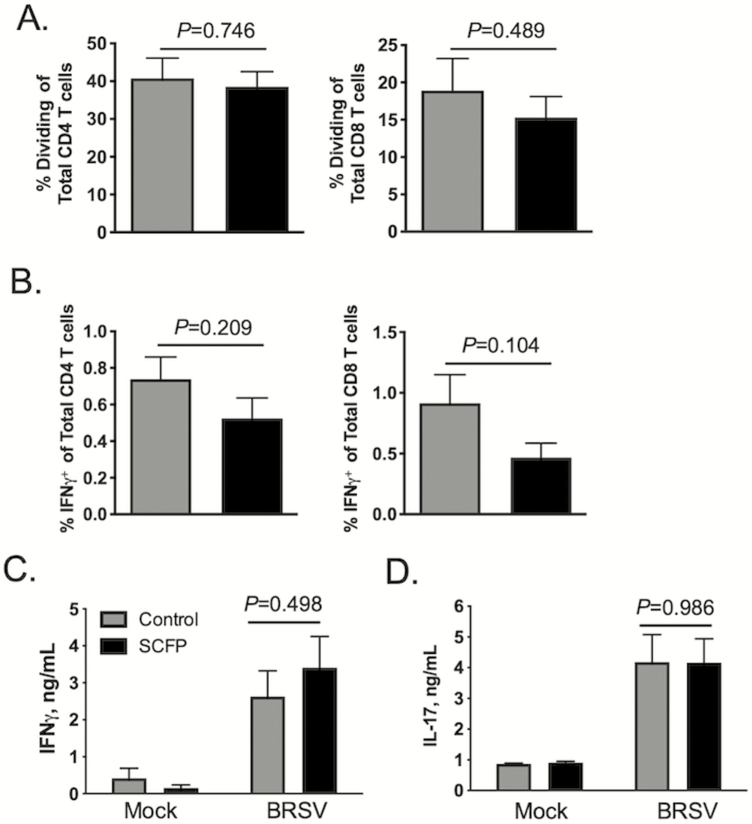

Figure 9.

SCFP treatment does not alter BRSV-specific T cell responses in the blood. Peripheral blood was collected on day 10 after BRSV infection. PBMCs were isolated and cryopreserved. (A) PBMCs were thawed and labeled with CellTrace Violet proliferation dye, and 5 × 105 cells/well were cultured for 6 d in the presence or absence of 0.01 MOI BRSV strain 375. CD4 (left) and CD8 (right) T cell proliferation was analyzed by flow cytometry for CellTrace dilution. Control wells remained unstimulated (Mock). T cell proliferation was analyzed using the gating strategy presented in Supplementary Figure S1. Background proliferation was subtracted, and results represent change over unstimulated samples; n = 10 control calves; n = 12 SCFP calves. Data are presented as means ± SEM. P-values were determined by student’s t-test. (B) Virus-specific IFNγ production was analyzed in PBMCs on day 10 postinfection; 1 × 106 cells/well were stimulated in vitro with 0.01 MOI BRSV strain 375 for 16 h. Cells were then stained for intracellular IFNγ expression and analyzed by flow cytometry using the gating strategy outlined in Supplementary Figure S2. The frequency of circulating CD4+ IFNγ + (left) and CD8+ IFNγ + (right) is shown. Background IFNγ + production was subtracted and results represent change over unstimulated samples; n = 10 control calves; n = 12 SCFP calves. Data represent means ± SEM. P-values were determined by student’s t-test. (C and D) Cell culture supernatants were collected from the PBMCs cultures in (A) and analyzed by commercial ELISA kit for (C) IFNγ and (D) IL-17; n = 10 control calves; n = 12 SCFP calves. Data represent means ± SEM.