Abstract

GAMYBs are positive GA signaling factors that exhibit essential functions in reproductive development, particularly in anther and pollen development. However, there is no direct evidence of the regulation of any GAMYB in these biological processes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Here, we identified a tomato GAMYB-like gene, SlMYB33, and characterized its specific roles. SlMYB33 is predominately expressed in the stamens and pistils. During flower development, high mRNA abundance of SlMYB33 is detected in both male and female organs, such as microspore mother cells, anthers, pollen grains, and ovules. Silencing of SlMYB33 leads to delayed flowering, aberrant pollen viability, and poor fertility in tomato. Histological analyses indicate that SlMYB33 exerts its function in pollen development in the mature stage. Further transcriptomic analyses imply that the knockdown of SlMYB33 significantly inhibits the expression of genes related to flowering in shoot apices, and alters the transcription of genes controlling sugar metabolism in anthers. Taken together, our study suggests that SlMYB33 regulates tomato flowering and pollen maturity, probably by modulating the expression of genes responsible for flowering and sugar metabolism, respectively.

Subject terms: Plant development, Developmental biology

Introduction

GAMYB encodes an R2R3-MYB transcription factor that acts as a positive gibberellin (GA) signaling factor1. The first GAMYB was isolated from aleurone cells in barley (Hordeum vulgare) and controls the expression of most GA-inducible genes2–4. GAMYB has been shown to be a target of microRNA 159 (miR159), a highly conserved miRNA family in the common ancestor of all embryophytes5. MiR159 controls the cleavage of GAMYB mRNA6–8.

A series of studies have reported the differing roles of GAMYBs in the regulation of flowering. Lolium temulentum LtGAMYB is mainly expressed in the shoot tip, and its transcript level is upregulated in parallel with an increased GA content during the floral transition9. The GAMYB family has three members in Arabidopsis: AtMYB33, AtMYB65, and AtMYB10110. When Arabidopsis plants are transferred from short-day to long-day conditions or treated with exogenous GA under short days, flowering occurs, and the expression of AtMYB33 and LEAFY (LFY), the floral meristem-identity gene, increases in the shoot apex at that time. Furthermore, the expression timing and pattern of AtMYB33 precede and overlap with those of LFY at the shoot apex, and AtMYB33 can bind to a specific 8-bp sequence in the LFY promoter10. These observations imply that GAMYB may be involved in GA-regulated flowering via the transcriptional activation of the LFY gene. However, several studies have suggested that loss-of-function mutants of GAMYBs do not exhibit altered flowering in Arabidopsis and rice (Oryza sativa)11,12. Moreover, the manipulation of miR159 controls flowering time in some cases by regulating the expression level of its target GAMYB. For instance, the overexpression of miR159 delays flowering by inhibiting AtMYB33 under a short-day photoperiod in Arabidopsis6, but another line of evidence showed that the flowering time remains normal under long-day conditions in miR159-overexpressing plants, which causes the downregulation of AtMYB1018. In contrast, the Arabidopsis mir159ab double mutant displays late flowering under short days, but shows no alteration of flowering time under long days11. In addition, the repression of miR159, which increases GAMYB expression, accelerates flowering in gloxinia (Sinningia speciosa)13 but delays flowering in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum)14.

GAMYBs also play an essential role in flower development, particularly in stamen development. In barley, the expression of HvGAMYB is predominately detected in the anthers, and HvGAMYB overexpression leads to reduced anther length, failure of anther dehiscence, and male sterility, mimicking the effect of excessive GA on flower development15. In rice, OsGAMYB is strongly expressed in the shoot apex, stamen primordia, and tapetum cells at the reproductive stage. Loss of function of OsGAMYB results in some defects in anther and pollen development12,16. Moreover, OsGAMYB has been found to participate in the GA-regulated formation of exines and Ubisch bodies and the programmed cell death (PCD) of tapetal cells; specifically, the direct induction of CYP703A3 by OsGAMYB is key to the formation of exines and Ubisch bodies17. The Arabidopsis myb33 myb65 double mutant shows shorter stamens that fail to fully extend to the stigma, and displays defective pollen development owing to the hypertrophy of the tapetum at the microspore mother cell (MMC) stage, resulting in male sterility. However, single mutants (myb33 or myb65) do not exhibit aberrant phenotypes, indicating crucial functional redundancy between AtMYB33 and AtMYB657. The overexpression of miR159, repressing its target AtMYB33, also causes anther defects and male sterility6. There are three GAMYB-like genes in cucumber (Cucumis sativus): CsGAMYB1, CsGAMYB2, and CsGAMYB3. The silencing of CsGAMYB1 decreases the number of male flower nodes and increases that of female flower nodes, leading to a significant change in cucumber sex expression18,19. In tomato, the GAMYB homolog SlGAMYB1 has been identified, which is expressed in the embryo and endosperm during seed germination and in young vegetative tissues20.

Therefore, although GAMYBs have been studied extensively in plants, there is no direct evidence of the regulation of any GAMYB (including SlGAMYB1) during flowering and pollen development in tomato, which is an important commercial crop and a model species for studying flower and fruit development21,22. Therefore, in the present study, we revealed the specific roles of SlMYB33, a GAMYB-like gene, in flowering and pollen development in tomato. We found that SlMYB33 was mainly expressed in stamens and pistils. The knockdown of SlMYB33 resulted in delayed flowering, aberrant pollen maturity, and remarkably decreased fertility. RNA-Seq analyses revealed that SlMYB33 probably achieves its positive roles in tomato flowering and pollen maturity by regulating the expression of genes involved in flowering and sugar metabolism, respectively.

Results

Identification of the GAMYB-like gene SlMYB33 from tomato

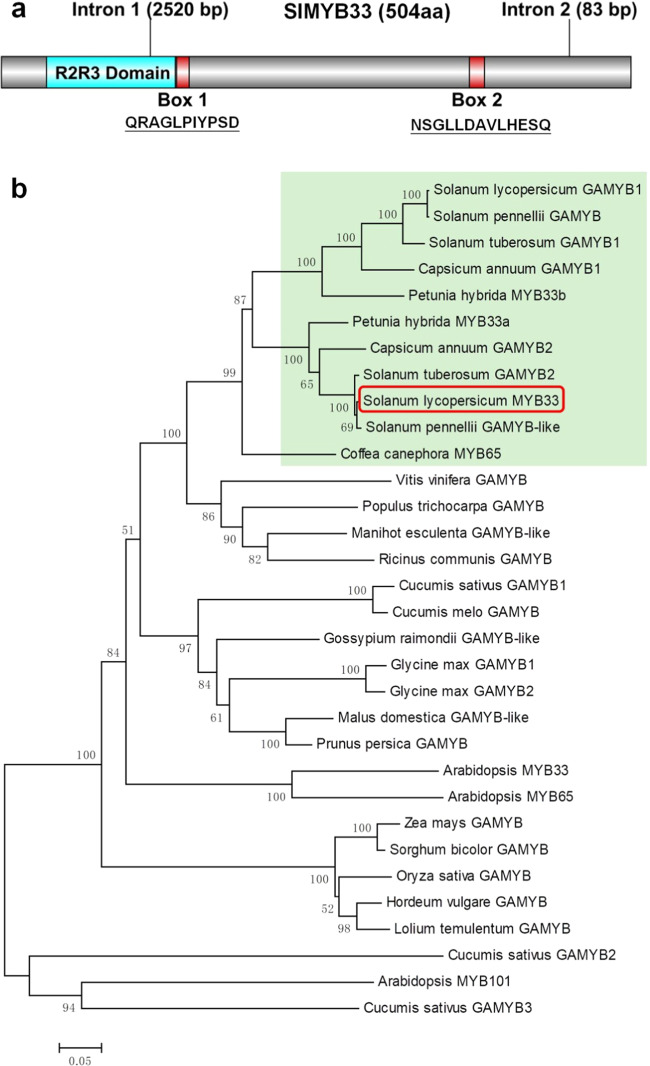

Following a BLAST search in the Solanaceae Genomics Network, we identified two GAMYB-like genes, SlGAMYB1 (Solyc01g009070) and SlMYB33 (Solyc06g073640), in tomato. Since the SlGAMYB1 gene has been reported previously20, we focused on SlMYB33 in this study. SlMYB33 contains three exons and two introns (Fig. 1a), similar to the GAMYB orthologs found in barley, Arabidopsis, and cucumber10,18. The full-length CDS of SlMYB33 consists of 1515 bp and encodes 504 amino acids. Previous studies have reported that GAMYBs belong to the R2R3-MYB family and contain helix-turn-helix repeats R2 and R3 and three typically conserved motifs, Box 1, Box 2, and Box 310,23. Analyses of the protein domain structure and the sequence alignments of the amino acid residues revealed that SlMYB33 also includes an R2R3-repeat DNA-binding domain and conserved Box 1 (QRAGLPIYPSD) and Box 2 (NSGLLDAVLHESQ) motifs, but no Box 3 (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. S1). SlMYB33 shares the highest overall identity with cucumber CsGAMYB1 (40.49%); however, within the R2R3 sequence alone, the identity of AtMYB33, AtMYB65, CsGAMYB1, and HvGAMYB with SlMYB33 is 84.62%, 83.65%, 90.38%, and 89.42%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 1. Structural and phylogenetic analyses of SlMYB33.

a Protein domain structure of SlMYB33. b Phylogenetic analysis of GAMYB homologs in different species. SlMYB33 is indicated in the red box. The species in the light-green box all belong to the Solanaceae family. The gene ID of each GAMYB protein used for this analysis is provided in the “Accession Numbers” list

To reveal the evolutionary relationships between SlMYB33 and other GAMYB homologs, 32 predicted GAMYB proteins from 22 species were included in a phylogenetic analysis. As shown in Fig. 1b, the GAMYBs of Solanaceae species, including tomato, potato (Solanum tuberosum), pepper (Capsicum annuum), Petunia hybrida, and Coffea canephora, were placed in a single group, suggesting that they may share a common origin. Among these sequences, SlMYB33, Solanum pennellii (a wild tomato species) GAMYB-like, and potato GAMYB2 fall into the same clade, which is highly distinct from that of Arabidopsis MYB33 and MYB65. In addition, SlGAMYB1 is located in the same cluster with Solanum pennellii GAMYB and potato GAMYB1. These results implied that tomato SlMYB33 belongs to the GAMYB family.

SlMYB33 expression pattern in tomato

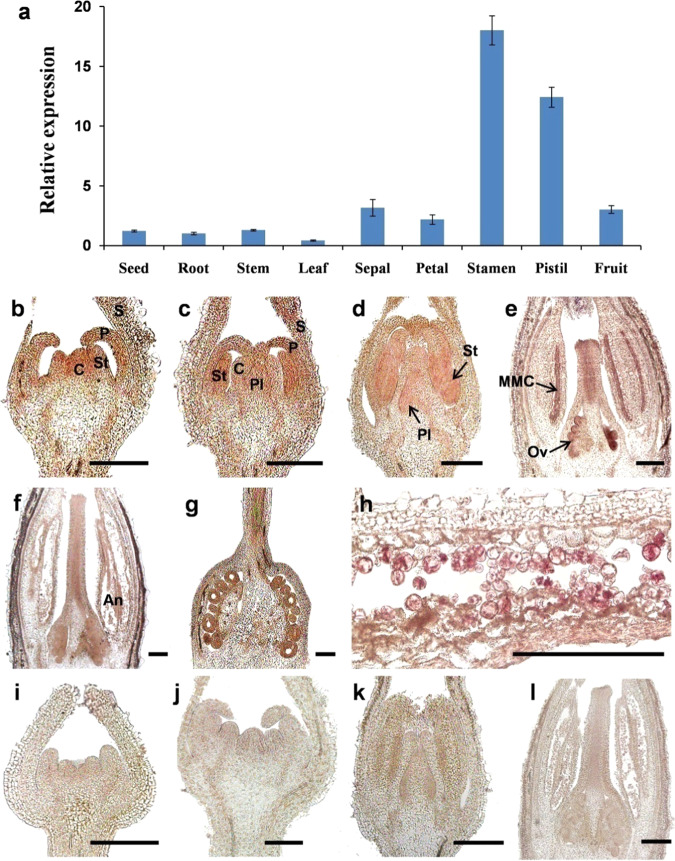

To address the possible functions of SlMYB33, we first evaluated its expression profiles in various tissues of tomato (Micro-Tom) through qRT-PCR. SlMYB33 is mainly expressed in stamens and pistils, in which its transcript levels are at least fourfold higher than those in the seeds, roots, stems, leaves, sepals, petals, and fruits (Fig. 2a). This result was validated in the TomExpress database, and we found that the expression pattern of SlMYB33 in TomExpress showed a similar trend to the results of the qRT-PCR analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2). We also obtained expression data for another tomato GAMYB gene, SlGAMYB1, from TomExpress. SlGAMYB1 is highly expressed in flower buds compared with other tissues (Supplementary Fig. S2). These observations pointed to a potential role of SlMYB33 in tomato flower development, and SlGAMYB1 may have a similar function.

Fig. 2. Expression analyses of SlMYB33 in tomato.

a qRT-PCR analyses of SlMYB33 in different tomato tissues. The various tissues in different developmental stages included in this analysis were as follows: seeds, red ripe fruit stage; roots, stems, and leaves, four true leaf-stage plants; sepals, petals, stamens, and pistils, 5-mm-length flower buds; fruits, 7-DPA (days post anthesis) stage. Values are the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. b–l In situ hybridization of SlMYB33 in tomato flowers at different developmental stages. b–h Longitudinal sections of flower buds hybridized with the antisense probe at stage 4 (b), stage 6 (c), stage 7 (d), stage 9 (e), stage 12 (f), and stage 14 (g, h). i–l Negative controls hybridized with the sense probe (no signals were detected). S sepal, P petal, St stamen, C carpel, Pl placenta, MMC microspore mother cell, Ov ovule, An anther. Bars = 200 μm

Next, we performed in situ hybridization to analyze the spatial/temporal expression of SlMYB33 during tomato flower development in detail (Fig. 2b–l). SlMYB33 transcripts were detected in the developing sepals, petals, stamens, carpels, and placenta primordia in early stages (stages 4 and 6, Fig. 2b, c)24, after which SlMYB33 expression was restricted to the stamens and placentae (stage 7, Fig. 2d). In later developmental stages, SlMYB33 was persistently expressed in the developing microspore mother cells (MMC), anthers, pollen grains, and ovules (stages 9–14, Fig. 2e–h). As negative controls, no signals were detected under SlMYB33 sense probe hybridization (Fig. 2i–l). Our results suggested that SlMYB33 may play an important role in both male and female gametophyte development in tomato.

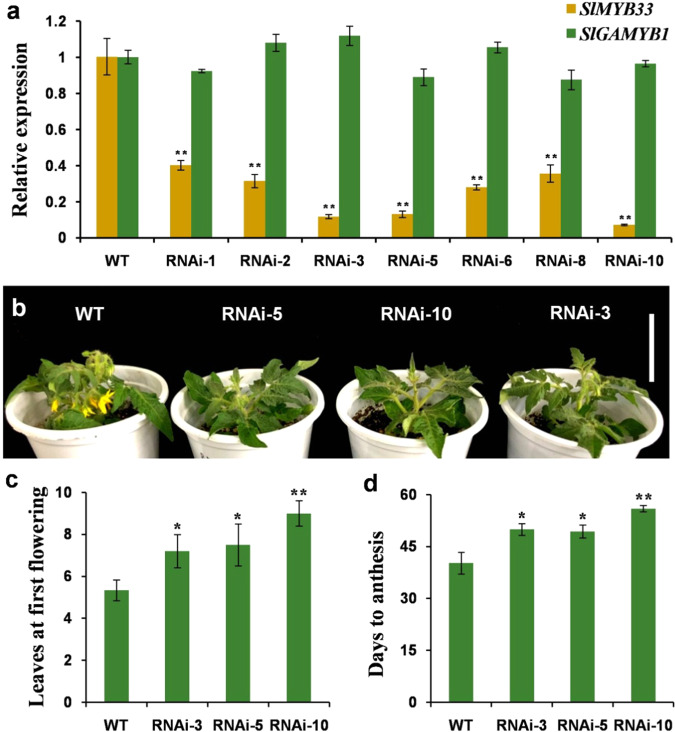

Knockdown of SlMYB33 results in delayed flowering in tomato

To determine the biological function of SlMYB33, we attempted to inhibit its expression in Micro-Tom plants using gene-silencing technology. An RNA interference (RNAi) construct under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter was generated and transformed into the tomato plants. Following PCR analysis, ten independent SlMYB33-RNAi lines were obtained. Among these lines, seven displayed significant reductions in SlMYB33 transcript abundance by 60–92% in the flowers, whereas no apparent changes in SlGAMYB1 expression were observed (Fig. 3a), suggesting that only SlMYB33 was effectively knocked down. Due to the lower SlMYB33 expression levels in lines 3, 5, and 10 compared with the other lines, these three lines were chosen for further analysis (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. SlMYB33-RNAi results in delayed flowering in tomato.

a Expression analyses of SlMYB33 and SlGAMYB1 in the flower buds (5-mm length) of WT plants and SlMYB33-RNAi lines by qRT-PCR. Each value is the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. b Wild-type (WT) plants and progenies of SlMYB33-RNAi lines. All genotypes were sown at the same time and grown under the same environmental conditions. When the flowers of the WT plants open, the RNAi lines are in the vegetative stage. Bar = 5 cm. c Numbers of leaves at first flowering in WT and the progenies of SlMYB33-RNAi lines. Each value is the mean ± SD of three biological replicates, and six plants were examined for each replicate. d Days to anthesis in WT and the progenies of SlMYB33-RNAi lines. Each value is the mean ± SD of three biological replicates, and six plants were examined for each replicate. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the RNAi lines and WT by Student’s t tests (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01)

Previous studies have reported the potential effect of GAMYB genes on flowering6,9,10; therefore, the flowering time in the T1 generation of SlMYB33-RNAi lines was recorded. For each RNAi line, 18 T1 plants exhibiting apparent suppression of SlMYB33 were selected for this analysis (Supplementary Fig. S3). We found that flowering was initiated in the progenies of three transgenic lines after the emergence of 7.2–9 leaves, compared with 5.3 leaves in WT (wild-type) plants (Fig. 3c). Accordingly, the first flower opened at 50–56 days after sowing in the progenies of SlMYB33-RNAi lines, which was later than the time of 40.3 days observed in the WT plants (Fig. 3b, d). Moreover, the extension of the flowering time in the RNAi lines was negatively correlated with SlMYB33 expression; for instance, the lowest SlMYB33 mRNA level in the RNAi-10 line led to the most severe late-flowering phenotype (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Fig. S3). In addition, we investigated the flowering time of T1 plants of three null SlMYB33-RNAi lines (RNAi-4, RNAi-7, and RNAi-9) that displayed no obvious repression of SlMYB33 (Supplementary Fig. S4a). No significant changes in the numbers of leaves produced before the first flower were found in these transgenic lines compared with WT plants (Supplementary Fig. S4b). These data suggested that SlMYB33 can promote flowering in tomato.

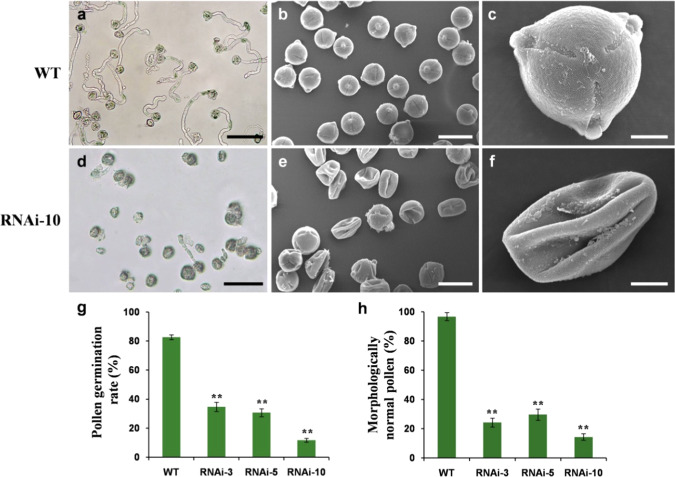

Suppression of SlMYB33 leads to aberrant pollen maturity and poor fertility

To evaluate whether SlMYB33 could affect anther and pollen development similarly to a typical GAMYB homolog7,12,16,17, the pollen phenotypes were analyzed in the SlMYB33-RNAi lines. As expected, a majority of the pollen grains were aberrant in the RNAi lines (Fig. 4). Here, the in vitro pollen germination assay indicated that 65–88% of the pollen grains in the SlMYB33-RNAi lines had lost germination ability, compared with only 17% in the WT (Fig. 4a, d, g). Further microscopic observations by SEM revealed that the pollen grains from the RNAi lines were shrunken and collapsed compared with those of the WT (Fig. 4b, c, e, f). Quantitative analyses showed that 70–86% of the transgenic pollen grains displayed an abnormal morphology, whereas this percentage was only 3% in the WT (Fig. 4h).

Fig. 4. Characterization of pollen phenotypes in SlMYB33-RNAi lines.

a, d In vitro pollen germination tests in WT (a) and SlMYB33-RNAi line 10 (d). Bars = 100 μm. b, e Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of pollen grains in WT (b) and RNAi-10 (e). Bars = 25 μm. c, f Single pollen grain morphology under SEM in WT (c) and RNAi-10 (f). Bars = 5 μm. g, h Quantification of the pollen germination rate (g) and percentage of morphologically normal pollen grains (h) in WT and different RNAi lines. Values are the means ± SD of ten biological replicates from three plants, and three to four flowers were examined in each plant. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the RNAi lines and the WT by Student’s t test (**P < 0.01)

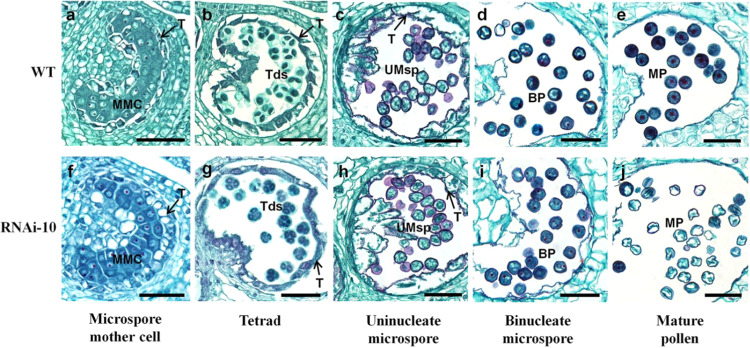

To dissect how SlMYB33 regulates pollen development, histological analyses of flower buds at different stages were performed in WT and RNAi plants (Fig. 5). Among the five stages of tomato pollen development24, no evident abnormalities were found in the microspore mother cells (MMCs), tetrads, or uninucleate microspores in the anthers of RNAi-10 plants (Fig. 5a–c) compared to those of the WT (Fig. 5f–h). During the binucleate stage, the transgenic pollen grains were slightly shrunken and irregular but showed no defects in their structures (Fig. 5d, i). However, a striking phenotype was detected at the mature stage. In contrast to the WT, most of the mature pollen grains in RNAi-10 were severely collapsed and shrunken, which may be due to the degradation of the cytoplasm (Fig. 5e, j). In addition, there was no obvious change in transgenic tapetum development (Fig. 5), which can be mediated by GAMYB homologs in other species such as Arabidopsis and rice7,11,17.

Fig. 5. Suppression of SlMYB33 disturbs pollen maturity.

Transverse sections of flower buds at the microspore mother cell stage (a, f), tetrad stage (b, g), uninucleate microspore stage (c, h), binucleate microspore stage (d, i), and mature pollen stage (e, j) in WT and RNAi-10. MMC microspore mother cell, T tapetum, Tds tetrads, UMsp uninucleate microspore, BP binucleate pollen, MP mature pollen. Bars = 50 μm

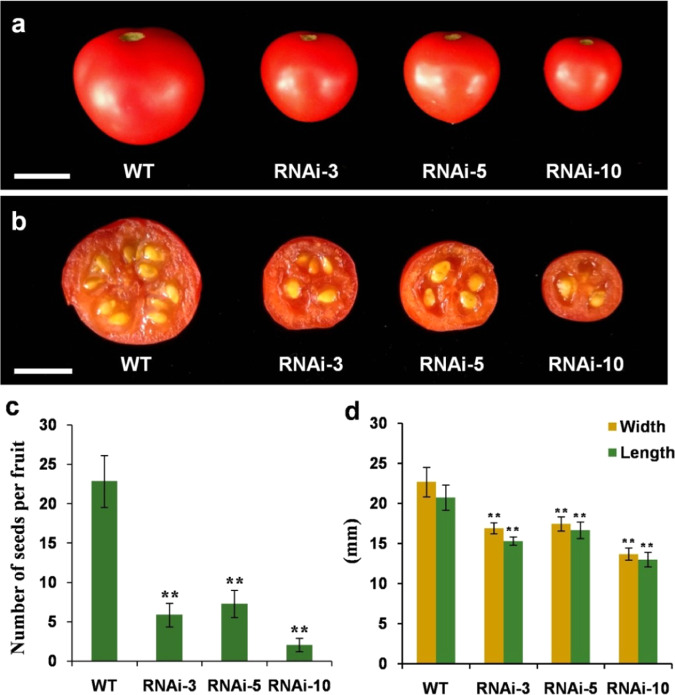

Along with aberrant pollen development (Figs. 4 and 5), the suppression of SlMYB33 leads to a significant reduction in the fertility of tomato. As shown in Fig. 6, each fruit of the SlMYB33-RNAi lines produced only 3.1–7.3 seeds, which was a markedly lower number than 22.9 seeds recorded in the WT (Fig. 6b, c). Fruit size was also obviously decreased in the transgenic plants (fruit width of 13.7–17.5 mm, length of 13.0–16.7 mm) compared with the WT (fruit width of 22.7 mm, length of 20.8 mm), and was quantitatively related to seed number (Fig. 6a, d). Therefore, we speculated that this change in fruit size might be caused by the reduced seed number. In conclusion, the repression of SlMYB33 disrupts pollen maturity, resulting in poor fertility accompanied by smaller fruit in tomato.

Fig. 6. The suppression of SlMYB33 affects the fertility and fruit size of tomato.

a Fruits of WT and SlMYB33-RNAi lines. b Transverse sections of the fruits of WT and SlMYB33-RNAi lines. c Numbers of seeds per fruit in WT and different RNAi lines. d Fruit sizes in WT and different RNAi lines. Values are the means ± SD of three independent plants, and 15 fruits were examined for each plant. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the RNAi lines and the WT by Student’s t test (**P < 0.01). Bars = 1 cm

Knockdown of SlMYB33 restricts the expression of genes controlling flowering

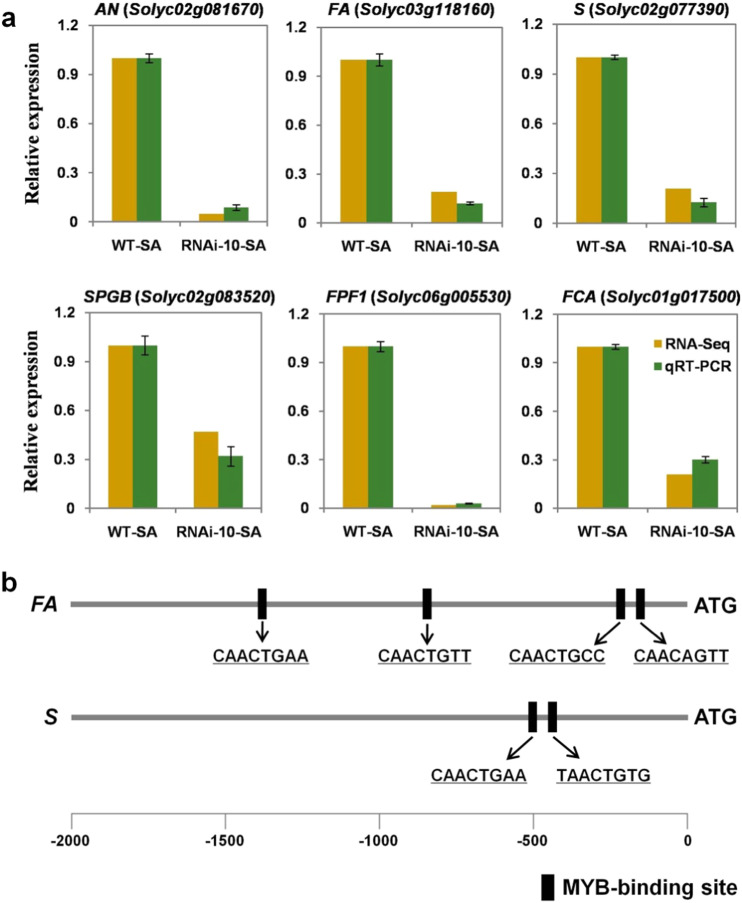

To identify the potential genes and molecular pathways involved in SlMYB33-regulated tomato flowering, transcriptome analysis was performed in shoot apices (30-day-old, not flowering) from the SlMYB33-knockdown line RNAi-10 and WT plants by the digital gene expression (DGE) approach25. Using a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and a fold change (FC) > 2 as significance cutoffs, we identified 2388 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), among which 1689 genes were upregulated, and 699 genes were downregulated in the RNAi-10 shoot apices compared with those of the WT (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Table S2). Through careful examination, we observed that the expression levels of several genes responsible for tomato flowering were dramatically decreased in the shoot apices of the RNAi lines, including the ANANTHA (AN), FALSIFLORA (FA), COMPOUND INFLORESCENCE (S), and SPGB genes, encoding the F-box protein UNUSUAL FLORAL ORGANS (UFO), the transcription factor LFY, the homeobox transcription factor WUSCHEL-HOMEOBOX9 (WOX9), and the basic region/leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor SP-INTERACTING G-BOX (SPGB), respectively (Fig. 7a; Supplementary Table S2)26–28. The tomato homologs of two genes promoting flowering in Arabidopsis and rice, FLOWERING-PROMOTING FACTOR1 (FPF1) and FLOWERING TIME CONTROL LOCUS A (FCA), were also significantly downregulated (Fig. 7a; Supplementary Table S2)29–34. qRT-PCR analysis was performed for these six DEGs, and the results revealed the same expression pattern as the RNA-Seq analysis. Therefore, the AN, FA, S, SPGB, FPF1, and FCA genes may be involved in SlMYB33-regulated flowering in tomato. Given the ability of GAMYB to bind to the promoters of target genes3,10, we further analyzed the cis-acting elements in the promoters of these six DEGs. As shown in Fig. 7b, the promoters of the FA and S genes contained four and two MYB-binding sites, respectively, which were highly conserved with the 8-bp GAMYB-binding site (CAACTGTC) with a C/TAAC core in Arabidopsis10, implying that FA and S are putative candidate target genes of SlMYB33 in the regulation of tomato flowering.

Fig. 7. Knockdown of SlMYB33 inhibits the expression of flowering-related genes, and FA and S act as putative candidate target genes of SlMYB33.

a Expression analyses of flowering-related genes in the shoot apices of WT and RNAi-10 plants. Three independent samples used for qRT-PCR were collected at the same developmental stage as those used for RNA-Seq. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 3). b Analyses of the cis-acting elements in the promoters of FA and S. The 2-kb promoter sequence (before ATG) was acquired for this analysis. SA shoot apex

SlMYB33 affects the expression of sugar metabolism genes

We also carried out RNA-Seq analysis to explore the possible gene networks through which SlMYB33 regulates tomato pollen maturity in anthers from the transgenic RNAi-10 and WT plants. Given that gene expression differences usually occur before phenotypic changes, the anthers were harvested before the mature pollen stage (late binucleate microspore stage) and used for transcriptome analysis. Through the DGE approach, a total of 1332 DEGs, including 676 upregulated genes and 656 downregulated genes, were identified (Supplementary Tables S1 and S3). Thereafter, KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) classification was performed. The DEGs were assigned to 20 functional categories, among which “carbohydrate metabolism” was the most represented pathway, including 41 DEGs (Fig. 8a). Carbohydrate metabolism was then classified into 13 subgroups (Fig. 8b), among which starch and sucrose metabolism are essential for pollen development, especially for pollen maturity35–39. Further examination revealed a dramatic reduction in the transcript levels of most of the genes grouped into the starch and sucrose metabolism pathways (Table 1). For instance, Lin7, encoding cell wall invertase (CWIN), which hydrolyzes sucrose into glucose and fructose39, was significantly downregulated by 21.5-fold in the transgenic anthers compared with the WT. In addition, the expression levels of the following genes were obviously decreased: one gene encoding sucrose-phosphate synthase (SPS), which is a key regulator of sucrose synthesis, two genes that encode sucrose synthase (SUS), responsible for sucrose degradation, and one gene encoding trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS), involved in the production of trehalose-6-phosphate (T6P), which acts as a signaling molecule in sensing sucrose availability and promoting starch and cell wall biosynthesis40,41. We further found that the transcripts of two genes encoding 6-phosphofructokinase and fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, which are two key enzymes in the glycolysis pathway, were depressed in the RNAi line. Moreover, a gene for β-glucosidase (GLU), which can release glucose from the inactive glucoside42, is upregulated. In addition, the gene for ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase), a key enzyme for starch synthesis40,43, exhibited a reduced mRNA level; however, a similar expression profile was detected in the β-amylase gene responsible for starch degradation. In addition, the expression of the gene (no classification) encoding sugar transporter protein 13 (SlSTP13) was remarkably inhibited (Table 1). qRT-PCR assays of the above genes showed the same expression trend as the RNA-Seq analysis (Supplementary Fig. S5). These results indicated that the silencing of SlMYB33 disrupts tomato pollen maturity at least partly by repressing the transcription of genes related to starch and sucrose metabolism as well as sugar transport.

Fig. 8. KEGG classification of DEGs in anthers between RNAi-10 and WT.

a Functional categories of DEGs. b Secondary classification of the carbohydrate metabolism pathway

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes in the anthers of SlMYB33-RNAi and WT plants

| Functional category | Gene ID | Gene annotation | FC | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | Solyc09g010090 | Cell wall invertase (Invertase 7, Lin7) | −21.53 | 2.76E–05 |

| Solyc11g045110 | Sucrose-phosphate synthase (SPS) | −10.13 | 2.78E–02 | |

| Solyc07g042550 | Sucrose synthase (SUS3) | −4.02 | 4.10E–02 | |

| Solyc12g040700 | Sucrose synthase | −3.19 | 4.23E–05 | |

| Solyc02g071590 | Trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS) | −2.07 | 7.14E–03 | |

| Solyc04g015200 | 6-Phosphofructokinase 2 | −2.06 | 8.53E–06 | |

| Solyc07g065900 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | −3.88 | 2.43E–04 | |

| Solyc08g044510 | β-Glucosidase (GLU) | 3.28 | 3.28E–02 | |

| Solyc12g011120 | ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) | −3.51 | 1.49E–02 | |

| Solyc09g091030 | β-Amylase 1 | −3.10 | 3.37E–02 | |

| Solyc03g005150 | Sugar transporter protein 13 (SlSTP13) | −4.15 | 4.47E–02 | |

| Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | Solyc06g009190 | Pectinesterase (PE) | 2.47 | 6.27E–05 |

| Solyc05g047590 | Pectinesterase (PE) | 2.02 | 3.56E–02 | |

| Solyc03g111690 | Pectate lyase (PL) | 2.08 | 2.56E–02 | |

| Solyc06g068040 | Polygalacturonase (PG) | −3.28 | 4.95E–03 |

Furthermore, we observed remarkable expression differences in several genes (belonging to the “pentose and glucuronate interconversions” pathway) controlling cell wall degradation in transgenic RNAi anthers compared with those of the WT. Here, two pectinesterase (PE) genes and one pectate lyase (PL) gene displayed upregulation, whereas one polygalacturonase (PG) gene showed downregulation (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S5), revealing the possible involvement of these genes in pollen collapse in SlMYB33-RNAi plants.

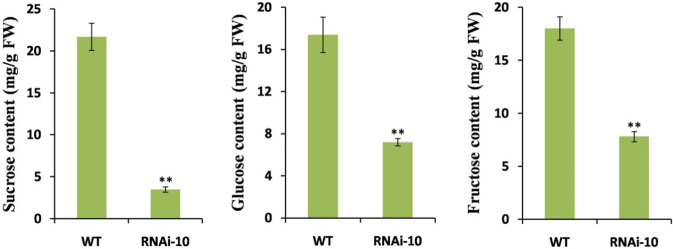

We then performed metabolite analysis to examine whether the changes in the expression of genes related to sugar metabolism could influence the contents of carbohydrates. As expected, we found that the knockdown of SlMYB33 significantly decreased the sucrose content by 6.2-fold in anthers at the mature pollen stage, and the concentrations of glucose and fructose also declined in the RNAi-10 plants (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Sucrose, glucose, and fructose concentrations in WT and RNAi-10 anthers at the mature pollen stage.

Values are means ± SD of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between RNAi-10 and WT plants by Student’s t test (**P < 0.01)

Discussion

GAMYB functions in the regulation of flowering

Our results suggested that the knockdown of SlMYB33 delays tomato flowering (Fig. 3). However, there are differing reports about the roles of GAMYBs in the regulation of flowering. Overexpression of miR159 in Arabidopsis ecotype Landsberg erecta causes late flowering through the downregulation of the target AtMYB33 under short days6; however, in Columbia, the overexpression of miR159, repressing AtMYB101, does not alter flowering time under long days8. It has also been reported that the loss of function of GAMYBs in Arabidopsis (Columbia background) and rice does not affect flowering11,12; moreover, the transcriptomes of the shoot apices are almost identical between WT and myb33 myb65 mutant in Arabidopsis11. Nevertheless, in gloxinia, the overexpression or repression of miR159 causes the downregulation or upregulation of GAMYB, leading to delayed or early flowering, respectively13. In contrast, a recent report demonstrated that transgenic tobacco plants with greater GAMYB levels exhibit a late-flowering phenotype14. These observations indicated that the functions of GAMYBs in flowering appear to be determined by a complex mechanism, which may be affected by differences in species or ecotypes. This is the first time that the direct downregulation of GAMYB has been shown to result in late flowering, providing novel evidence of the diversity of GAMYB functions in flowering.

SlMYB33 shows conserved and different roles in pollen development compared with its homologs

GAMYBs have been verified to positively regulate stamen development. Loss of function of GAMYBs leads to defects in stamen, anther, and pollen development, resulting in male sterility in Arabidopsis and rice7,12,16,17. In our study, expression analyses showed that tomato SlMYB33 is highly expressed in staminate organs (Fig. 2). The knockdown of SlMYB33 results in aberrant and inviable pollen grains (Fig. 4) and ultimately poor fertility (Fig. 6). Although fruit size also decreases in SlMYB33-RNAi lines, this may be a consequence of the reduced seed number in fruits (Fig. 6). These data supported the notion that SlMYB33 exhibits a conserved function in the promotion of pollen development.

Moreover, Arabidopsis myb33 myb65 and rice gamyb mutants show abnormal pollen development, owing to the loss of programmed cell death (PCD) and consequent endless hypertrophy of the tapetum7,11,17, demonstrating the importance of GAMYB in tapetum degradation. However, we did not find any obvious change in tapetum morphology at various developmental stages in SlMYB33-RNAi anthers compared with those of the WT, while the abortion of transgenic pollen grains was caused by damaged pollen maturity (Fig. 5), indicating that SlMYB33 plays a key role in tomato pollen maturity, rather than tapetum development. Therefore, despite the positive effect of both SlMYB33 and its homologs on pollen development, their regulatory mechanisms are different.

The potential effect of BR–GA crosstalk in phenotypes caused by the knockdown of SlMYB33

The tomato cultivar Micro-Tom was used as the studied plant material in this work. This genotype is a brassinosteroid (BR)-deficient mutant that exhibits a very dwarf phenotype with small fruits, but with no effect on flowers44. Further study suggested that BR and GA synergistically mediate vegetative growth in Micro-Tom45. BRs and GAs are two groups of growth-promoting phytohormones that can interact during many developmental processes46–49. BR induces GA biosynthesis to regulate plant growth, affecting processes such as cell elongation in rice50 and seed germination, hypocotyl elongation, and flowering in Arabidopsis51. Domagalska et al.52 also reported that the promotion effect of BR on flowering depends on the presence and concentration of GA in Arabidopsis52. On the other hand, GA can regulate plant growth by modulating BR biosynthesis and signaling. SPINDLY (SPY), a negative regulator of GA signaling, inhibits BR biosynthesis to mediate lamina joint bending53, whereas GERMOSTATIN RESISTANCE LOCUS 1 (GSR1), a positive regulator of GA signaling, stimulates BR biosynthesis to control root and leaf development and fertility in rice54. Moreover, DELLA proteins, which are the key repressors of GA signaling, interact with the positive regulators of BR signaling BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1 (BZR1)/BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR1 (BES1) and repress their activities. Therefore, GA can release the DELLA-modulated inhibition of BZR1/BES1 to induce BR responses and plant growth55–57.

In this work, phenotypic differences were observed between SlMYB33-RNAi lines and WT plants of the same genetic background (Micro-Tom), indicating that the phenotypes were caused by the silencing of SlMYB33, rather than BR deficiency in Micro-Tom. However, given the general feedback regulation of GA production by GA signaling58, together with the complexity of BR–GA interaction, it remains possible that the knockdown of SlMYB33 affects the crosstalk between BR and GA at the biosynthesis level and/or the signaling level, resulting in late flowering and abnormal pollen development.

Flowering-related genes are candidate genes regulated by SlMYB33

Our data revealed the important finding that the knockdown of SlMYB33 affects the expression of some genes controlling flowering, including FA, AN, S, SPGB, FPF1, and FCA (Fig. 7a). FA is an ortholog of Arabidopsis LFY, which is responsible for flower initiation26. Previous studies have demonstrated that the LFY can be activated by the application of GA, while GAMYBs influence flowering by regulating the GA responsiveness of the LFY promoter in Arabidopsis10,59. Likewise, FA can mediate tomato flowering, as demonstrated by a late-flowering phenotype with an increased number of leaves before the first inflorescence in the fa mutant26. AN encodes an F-box homolog of Arabidopsis UFO, while the S gene encodes a WOX9 transcription factor. S and AN are sequentially expressed during the phase transition from the inflorescence meristem to the floral meristem, and play overlapping roles in inflorescence architecture as well as floral identity. A mutation in either AN or S delays tomato flowering, leading to highly branched inflorescences21,27. Genetic interaction analysis shows that AN functions downstream of FA, demonstrating the crucial function of FA in flowering27. Here, our work revealed that the silencing of SlMYB33 results in late flowering (Fig. 3), and significantly reduces the transcript levels of FA, AN, and S (Fig. 7a). In addition, the promoters of the FA and S genes contain putative GAMYB-binding sites (Fig. 7b). Based on these findings, we speculated that SlMYB33 controls flowering partly via the transcriptional activation of the FA–AN pathway and the S gene. Between the FA and S candidates, the former is most likely a downstream target of SlMYB33, as indicated by the homology of SlMYB33 and FA to Arabidopsis AtMYB33 and LFY, respectively (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. S1)26, while AtMYB33 functions upstream of LFY10.

SlMYB33 probably modulates pollen maturity by regulating the expression of sugar metabolism genes

Our work also highlighted a potential role of SlMYB33 in mediating the expression of genes related to sugar metabolism (Fig. 8; Table 1), which is necessary for pollen development36,37. For pollen to be viable, the import of sufficient nutrients is essential to support a series of physiological activities. CWIN hydrolyzes sucrose into glucose and fructose, which are then taken up into pollen by hexose transporters following an apoplasmic pathway39,40,60. Previous studies have reported the crucial role of CWIN in pollen development. The downregulation of tobacco CWIN results in inviable pollen because of the loss of starch and cell wall integrity61. In addition, pollen sterility is attributable to a reduction in the expression of CWIN together with hexose transporter genes under cold stress in rice62. Accordingly, we identified a dramatic decrease in the expression of the tomato CWIN ortholog Lin7 (SlCWIN3)40, in SlMYB33-RNAi anthers (Table 1). Lin7 has been reported to be predominately expressed in tomato anthers63; however, its biological function is still elusive. Chen et al.35 speculated that Lin7 potentially plays a role in postmeiotic pollen development, while our data revealed a possible effect of Lin7 on pollen maturity in tomato, suggesting that the function of CWIN homologs in pollen development may be conserved. Moreover, one SPS and two SUS genes were obviously downregulated in transgenic anthers (Table 1). SPS is a key enzyme for sucrose synthesis, whereas SUS contributes to sucrose cleavage to generate UDP-glucose and fructose40. Likewise, SlSTP13, a sugar transporter gene, was inhibited in the transgenic lines (Table 1). STPs serve as hexose/H+ symporters and contribute to the transport of glucose and fructose from the cell wall to the cytoplasm64.

Starch is highly important as an energy source in the microsporangium, and is essential for pollen ontogeny38. AGPase catalyzes the first key step of starch biosynthesis65,66. Strikingly, SPS activity is positively correlated with starch accumulation67. Therefore, the downregulation of AGPase and SPS (Table 1) indicated that the starch concentration might be decreased in SlMYB33-RNAi anthers. Moreover, a reduced mRNA level of one gene encoding β-amylase was observed (Table 1); this enzyme is an exoenzyme responsible for starch cleavage to release maltose molecules38, suggesting that starch degradation is also influenced.

In conclusion, the abnormal pollen maturity observed in SlMYB33-knockdown plants might be caused at least in part by the restriction of sucrose and starch metabolism and sugar transport, leading to a lack of nutrient reserves in pollen grains. The decreased sucrose, glucose, and fructose contents detected in RNAi-10 anthers at the mature pollen stage (Fig. 9) provided further evidence to support this proposition.

The possible role of miR159 in SlMYB33-regulated flowering and pollen development

Through BLAST analysis with mature miR159 sequences from Arabidopsis in miRbase (http://www.mirbase.org)6,68, we found two miR159 members in tomato: miR159a (MIMAT0009141) and miR159b (MIMAT0042036) (Supplementary Fig. S6a). A binding site was then detected between SlMYB33 and miR159a/b (Supplementary Fig. S6b), suggesting that SlMYB33 may act as the target of miR159a and miR159b.

Previous reports have indicated that miR159 functions in a feedback-regulatory loop with GAMYB in Arabidopsis in which miR159 directs the downregulation of GAMYB activity and is then compensatorily upregulated by GAMYB6. Here, we performed comparative expression analyses of miR159a and miR159b between SlMYB33-knockdown and WT plants; however, no significant changes were observed in either the shoot apices or anthers (Supplementary Fig. S6c), implying that there may be no feedback regulation of miR159 by SlMYB33 in tomato.

Based on the above observations and the high conservation of the miR159 family5, we predicted that SlMYB33-regulated flowering and pollen development may be controlled by miR159 (a/b) in tomato, but without the involvement of a feedback-regulatory mechanism.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L. cv Micro-Tom) seeds were germinated in a petri dish at 28 °C in the dark for 3 days, and the seedlings were then cultured in a growth room under a 16-h/8-h photoperiod with day/night temperatures of 25 °C/18 °C. Water management and pest control were performed according to standard practices.

SlMYB33 cloning, sequence alignment, and phylogenetic analysis

Total RNA was extracted from tomato flower buds using an RNA extraction kit (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan), and cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa). The coding sequence (CDS) of SlMYB33 was amplified by PCR using gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S4). The protein domain structure of SlMYB33 was analyzed using the software DOG 2.0.

The amino acid sequences of related GAMYB proteins in various species were obtained from the Solanaceae Genomics Network (http://www.solgenomics.net), National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), or Phytozome v12.1 (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html) database. Then, multiple-sequence alignment was carried out using MEGA5 software69, and boxes highlighting conserved sequences were drawn using the online software BoxShade (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html). The phylogenetic analysis was conducted via the neighbor-joining method70 with MEGA5, and bootstrapping was performed with 1000 replications.

qRT-PCR analysis

For the gene expression assay, total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed using an RNA extraction kit (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan) and a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa), respectively. Then, quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was carried out using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (TaKaRa) with an Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, CA, United States). The tomato EF-1α gene served as the reference gene71. Each qRT-PCR assay was repeated with three biological samples. The relative expression levels of genes were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method.

For the mature miRNA159 expression analysis, the cDNA was generated through reverse transcription from the total RNA by using the miRcute miRNA First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). The qRT-PCR analysis was performed using an miRNA qPCR Detection Kit (SYBR Green) (TIANGEN). The tomato U6 small nuclear RNA gene was used as an internal control. The gene-specific primers used in these procedures are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

In situ hybridization

Developing tomato flower buds at various developmental stages24 were collected, fixed, embedded, sectioned, and subjected to in situ hybridization as described previously72. The sense and antisense probes for SlMYB33 were generated using SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase, respectively. The primers used for the synthesis of the probes are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

Construction of the RNAi vector and tomato transformation

A 496-bp fragment of the SlMYB33 coding sequence was amplified to produce the sense strand using primers containing Spe I and BamH I sites and the antisense strand using primers containing Asc I and Swa I sites. The two amplified fragments were cloned into the pFGC1008 vector in the reverse orientation. Then, the resulting SlMYB33-RNAi vector was transformed into tomato as described by Chen et al.35. The positive plants were verified through PCR testing. After self-crossing, the seeds of the T0 generation were harvested and then sown in the soil matrix together with those of the WT. The seedlings of the T1 lines and WT were cultured in a growth room under the same environmental conditions. To avoid the impact of external factors such as tissue culture procedures and antibiotics on phenotypic identification, the positive transformants of the T1 generation were selected by PCR examination rather than by antibiotic screening. The specific primers used for RNAi construct generation and the identification of transformants are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

Pollen germination

Pollen germination tests were performed according to Carrera et al.73. Briefly, pollen grains were collected and deposited on glass slides with germination medium (pH 5.8) containing 0.292 M sucrose, 1.27 mM Ca(NO3)2, 1.62 mM H3BO3, 1 mM KH2PO4, and 0.6% agarose. After incubation at 25 °C in the dark for 2 h, the germinated pollen grains were observed and counted using a microscope.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The mature anthers were collected and fixed overnight in 4% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C and washed with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 6.8) four times. The samples were dehydrated through an ethanol series (10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%), critical point dried using a desiccator, and coated with gold–palladium in an ion coater (Eiko IB5, Tokyo, Japan). Digital images of pollen morphology were observed using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi S-4800, Tokyo, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 2 kV74.

Histology

Samples of flower buds containing various developmental stages of pollen24,35 were fixed, embedded, transversely sectioned (5-μm thick), dewaxed, and stained as previously described75. The sections were stained with 1% sarranine and 0.5% Fast Green solution and viewed under a light microscope (Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a digital camera (Olympus DP72, Tokyo, Japan).

Transcriptome analysis

Total RNAs from the shoot apices and anthers at specified stages were extracted with an RNA kit (TaKaRa) and used for transcriptome analysis. Digital gene expression (DGE) libraries were constructed as described previously19. Three biological replicates were included in each library. RNA sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform using paired-end technology by Majorbio Corporation (Shanghai, China). Bioinformatics analysis of the DGE data was carried out using the free online platform of the Majorbio Cloud Platform (www.majorbio.com). The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the DESeq2 tool76 with an FDR (false discovery rate) < 0.05 and a fold change > 2. The KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) classification of DGEs was conducted with KOBAS 2.0 software77.

Analysis of the promoters of target genes

The 2-kb promoter sequences (before ATG) of the target genes were acquired, and the cis-acting elements were analyzed using the online database PlantCARE (http://www.bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/).

Determination of sucrose, glucose, and fructose contents

Anthers at the mature pollen stage were collected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The concentrations of sucrose, glucose, and fructose were measured by HPLC (Shimadzu LC-30A, Kyoto, Japan) following Chen’s method35, and sucrose (CAS: 57-50-1), D-( + )-glucose (CAS: 50-99-7), and D-(-)-fructose (CAS: 57-48-7, Sigma, USA) were used as the corresponding standards.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using Excel 2010. The significance of differences between the control and experiment groups was assayed using two-tailed Student’s t tests with SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) 23.0. The threshold values corresponding to P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 were indicated as * and **, respectively.

Accession numbers

The accession numbers of the GAMYB orthologs from various species used in this study are as follows: Arabidopsis MYB33 (At5g06100), MYB65 (At3g11440), MYB101 (At2g32460), Capsicum annuum GAMYB1 (CA01g13490), GAMYB2 (CA06g22300), Coffea canephora MYB65 (Cc01_g07440), Cucumis melo GAMYB (XP_008456639), Cucumis sativus GAMYB1 (Csa009014), GAMYB2 (Csa019830), GAMYB3 (Csa013555), Glycine max GAMYB1 (HM447241), GAMYB2 (HM447242), Gossypium raimondii GAMYB-like (Gorai.009G301100), Hordeum vulgare GAMYB (AAG22863), Lolium temulentum GAMYB (AAD31395), Malus domestica GAMYB-like (MDP0000147309), Manihot esculenta GAMYB-like (XP_021598631), Oryza sativa GAMYB (CAA67000), Petunia hybrida MYB33a (Peaxi162Scf00526g00820), MYB33b (Peaxi162Scf00342g00113), Populus trichocarpa GAMYB (XP_002313492), Prunus persica GAMYB (Prupe.2G050100), Ricinus communis GAMYB (XP_015577302), SlGAMYB1 (Solyc01g009070), SlMYB33 (Solyc06g073640), Solanum pennellii GAMYB (Sopen01g004560), GAMYB-like (Sopen06g030050), Solanum tuberosum GAMYB1 (PGSC0003DMG400022689), Solanum tuberosum GAMYB2 (PGSC0003DMG400005918), Sorghum bicolor GAMYB (Sobic.003G331100), Vitis vinifera GAMYB (XP_010651548), and Zea mays GAMYB (AIW47221).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figure S1-S6 and Table S1 and S4

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0101703 and 2016YFD0100204-30), Basic Research Projects of Natural Science of Shaanxi Province (2018JQ3063), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671273).

Author contributions

Y.Z. and Y.L. designed the experiments, Y.Z., B.Z., T.Y., J.Z., B.L., and X.Z. performed the experiments. Y.Z., B.Z., and T.Y. analyzed the data. Y.Z. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Yan Zhang, Bo Zhang

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41438-020-00366-1).

References

- 1.Fleet CM, Sun TP. A DELLAcate balance: the role of gibberellin in plant morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2005;8:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gubler F, Kalla R, Roberts JK, Jacobsen JV. Gibberellin-regulated expression of a myb gene in barley aleurone cells: evidence for Myb transactivation of a high-pI α-amylase gene promoter. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1879–1891. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.11.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gubler F, et al. Target genes and regulatory domains of the GAMYB transcriptional activator in cereal aleurone. Plant J. 1999;17:1–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuji H, et al. GAMYB controls different sets of genes and is differentially regulated by microRNA in aleurone cells and anthers. Plant J. 2006;47:427–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuperus JT, Fahlgren N, Carrington JC. Evolution and functional diversification of MIRNA genes. Plant Cell. 2011;23:431–442. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.082784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Achard P, Herr A, Baulcombe DC, Harberd NP. Modulation of floral development by a gibberellin-regulated microRNA. Development. 2004;131:3357–3365. doi: 10.1242/dev.01206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millar AA, Gubler F. The Arabidopsis GAMYB-like genes, MYB33 and MYB65, are microRNA-regulated genes that redundantly facilitate anther development. Plant Cell. 2005;17:705–721. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.027920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwab R, et al. Specific effects of microRNAs on the plant transcriptome. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gocal GF, et al. Long-day up-regulation of a GAMYB gene during Lolium temulentum inflorescence formation. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:1271–1281. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.4.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gocal GF, et al. GAMYB-like genes, flowering, and gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1682–1693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonso-Peral MM, et al. The microRNA159-regulated GAMYB-like genes inhibit growth and promote programmed cell death in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:757–771. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.160630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaneko M, et al. Loss-of-function mutations of the rice GAMYB gene impair alpha-amylase expression in aleurone and flower development. Plant Cell. 2004;16:33–44. doi: 10.1105/tpc.017327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, et al. Flowering time control in ornamental gloxinia (Sinningia speciosa) by manipulation of miR159 expression. Ann. Bot. 2013;111:791–799. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Z, et al. miR159 represses a constitutive pathogen defense response in tobacco. Plant Physiol. 2020;182:2182–2198. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray F, Kalla R, Jacobsen J, Gubler F. A role for HvGAMYB in anther development. Plant J. 2003;33:481–491. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z, Bao W, Liang W, Yin J, Zhang D. Identification of gamyb-4 and analysis of the regulatory role of GAMYB in rice anther development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010;52:670–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aya K, et al. Gibberellin modulates anther development in rice via the transcriptional regulation of GAMYB. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1453–1472. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.062935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, et al. A GAMYB homologue CsGAMYB1 regulates sex expression of cucumber via an ethylene-independent pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 2014;65:3201–3213. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, et al. Transcriptomic analysis implies that GA regulates sex expression via ethylene-dependent and ethylene-independent pathways in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong X, Bewley DJ. A GAMYB-like gene in tomato and its expression during seed germination. Planta. 2008;228:563–572. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0759-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lozano R, Gimenez E, Cara B, Capel J, Angosto T. Genetic analysis of reproductive development in tomato. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2009;53:1635–1648. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072440rl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlova R, et al. Transcriptional control of fleshy fruit development and ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 2014;65:4527–4541. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stracke R, Werber M, Weisshaar B. The R2R3-MYB gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2001;4:447–456. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brukhin V, Hernould M, Gonzalez N, Chevalier C, Mouras A. Flower development schedule in tomato Lycopersicon esculentum cv. sweet cherry. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2003;15:311–320. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eveland AL, et al. Digital gene expression signatures for maize development. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:1024–1039. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.159673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molinero-Rosales N, et al. FALSIFLORA, the tomato orthologue of FLORICAULA and LEAFY, controls flowering time and floral meristem identity. Plant J. 1999;20:685–693. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lippman ZB, et al. The making of a compound inflorescence in tomato and related nightshades. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park S, et al. Optimization of crop productivity in tomato using induced mutations in the florigen pathway. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:1337–1342. doi: 10.1038/ng.3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kania T, Russenberger D, Peng S, Apel K, Melzer S. FPF1 promotes flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1327–1338. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.8.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melzer S, Kampmann G, Chandler J, Apel K. FPF1 modulates the competence to flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1999;18:395–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu ML, et al. FPF1 transgene leads to altered flowering time and root development in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2005;24:79–85. doi: 10.1007/s00299-004-0906-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macknight R, et al. FCA, a gene controlling flowering time in Arabidopsis, encodes a protein containing RNA-binding domains. Cell. 1997;89:737–745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80256-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mouradov A, Cremer F, Coupland G. Control of flowering time: interacting pathways as a basis for diversity. Plant Cell. 2002;14:S111–S130. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JH, et al. Conservation and divergence of FCA function between Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;58:823–838. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-8105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L, et al. Evidence for a specific and critical role of mitogen-activated protein kinase 20 in uni-to-binucleate transition of microgametogenesis in tomato. N. Phytol. 2018;219:176–194. doi: 10.1111/nph.15150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai G, Faleri C, Del Casino C, Emons AM, Cresti M. Distribution of callose synthase, cellulose synthase, and sucrose synthase in tobacco pollen tube is controlled in dissimilar ways by actin filaments and microtubules. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:1169–1190. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.171371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruan YL, Patrick JW, Bouzayen M, Osorio S, Fernie AR. Molecular regulation of seed and fruit set. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:656–665. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castro AJ, Clement C. Sucrose and starch catabolism in the anther of Lilium during its development: a comparative study among the anther wall, locular fluid and microspore/pollen fractions. Planta. 2007;225:1573–1582. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0443-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wan H, Wu L, Yang Y, Zhou G, Ruan YL. Evolution of sucrose metabolism: the dichotomy of invertases and beyond. Trends Plant Sci. 2018;23:163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruan YL. Sucrose metabolism: gateway to diverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014;65:33–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Figueroa CM, Lunn JE. A tale of two sugars: trehalose 6-phosphate and sucrose. Plant Physiol. 2016;172:7–27. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao L, Liu T, An X, Gu R. Evolution and expression analysis of the β-glucosidase (GLU) encoding gene subfamily in maize. Genes Genom. 2012;34:179–187. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salerno GL, Curatti L. Origin of sucrose metabolism in higher plants: when, how and why? Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:63–69. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scott JW, Harbaugh BK. Micro-Tom. A miniature dwarf tomato. Fla. Agr. Exp. Sta. Circ. 1989;370:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marti E, Gisbert C, Bishop GJ, Dixon MS, Garcia-Martinez JL. Genetic and physiological characterization of tomato cv. Micro-Tom. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:2037–2047. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li XJ, et al. DWARF overexpression induces alteration in phytohormone homeostasis, development, architecture and carotenoid accumulation in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016;14:1021–1033. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ross JJ, Quittenden LJ. Interactions between brassinosteroids and gibberellins: synthesis or signaling? Plant Cell. 2016;28:829–832. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tong H, Chu C. Reply: brassinosteroid regulates gibberellin synthesis to promote cell elongation in rice: critical comments on Ross and Quittenden’s letter. Plant Cell. 2016;28:833–835. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Unterholzner SJ, Rozhon W, Poppenberger B. Reply: interaction between brassinosteroids and gibberellins: synthesis or signaling? In Arabidopsis, both! Plant Cell. 2016;28:836–839. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tong H, et al. Brassinosteroid regulates cell elongation by modulating gibberellin metabolism in rice. Plant Cell. 2014;26:4376–4393. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.132092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Unterholzner SJ, et al. Brassinosteroids are master regulators of gibberellin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015;27:2261–2272. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Domagalska MA, Sarnowska E, Nagy F, Davis SJ. Genetic analyses of interactions among gibberellin, abscisic acid, and brassinosteroids in the control of flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimada A, et al. The rice SPINDLY gene functions as a negative regulator of gibberellin signaling by controlling the suppressive function of the DELLA protein, SLR1, and modulating brassinosteroid synthesis. Plant J. 2006;48:390–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang L, et al. OsGSR1 is involved in crosstalk between gibberellins and brassinosteroids in rice. Plant J. 2009;57:498–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bai MY, et al. Brassinosteroid, gibberellin and phytochrome impinge on a common transcription module in Arabidopsis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:810–817. doi: 10.1038/ncb2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gallego-Bartolomé J, et al. Molecular mechanism for the interaction between gibberellin and brassinosteroid signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13446–13451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119992109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li QF, et al. An interaction between BZR1 and DELLAs mediates direct signaling crosstalk between brassinosteroids and gibberellins in Arabidopsis. Sci. Signal. 2012;5:ra72. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Middleton AM, et al. Mathematical modeling elucidates the role of transcriptional feedback in gibberellin signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:7571–7576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113666109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eriksson S, Bohlenius H, Moritz T, Nilsson O. GA4 is the active gibberellin in the regulation of LEAFY transcription and Arabidopsis floral initiation. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2172–2181. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goetz M, et al. Metabolic control of tobacco pollination by sugars and invertases. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:984–997. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goetz M, et al. Induction of male sterility in plants by metabolic engineering of the carbohydrate supply. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:6522–6527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091097998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oliver SN, Dennis ES, Dolferus R. ABA regulates apoplastic sugar transport and is a potential signal for cold-induced pollen sterility in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:1319–1330. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Godt DE, Roitsch T. Regulation and tissue-specific distribution of mRNAs for three extracellular invertase isoenzymes of tomato suggests an important function in establishing and maintaining sink metabolism. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:273–282. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.1.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reuscher S, et al. The sugar transporter inventory of tomato: genome-wide identification and expression analysis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:1123–1141. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith AM, Denyer K, Martin C. The synthesis of the starch granule. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997;48:67–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tiessen A, et al. Starch synthesis in potato tubers is regulated by post-translational redox modification of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase: a novel regulatory mechanism linking starch synthesis to the sucrose supply. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2191–2213. doi: 10.1105/tpc.003640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheng WH, Chourey PS. Genetic evidence that invertase-mediated release of hexoses is critical for appropriate carbon partitioning and normal seed development in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999;98:485–495. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Bartel B. MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in plants. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006;57:19–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tamura K, et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Y, et al. Transcriptome profiling of tomato uncovers an involvement of cytochrome P450s and peroxidases in stigma color formation. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:897. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang X, et al. Transcription repressor HANABA TARANU controls flower development by integrating the actions of multiple hormones, floral organ specification genes, and GATA3 family genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:83–101. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.107854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carrera E, Ruiz-Rivero O, Peres LE, Atares A, Garcia-Martinez JL. Characterization of the procera tomato mutant shows novel functions of the SlDELLA protein in the control of flower morphology, cell division and expansion, and the auxin-signaling pathway during fruit-set and development. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:1581–1596. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.204552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu B, et al. Silencing of the gibberellin receptor homolog, CsGID1a, affects locule formation in cucumber (Cucumis sativus) fruit. N. Phytol. 2015;210:551–563. doi: 10.1111/nph.13801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang Y, Li Y, Zhang J, Muhammad T, Liang Y. Decreased number of locules and pericarp cell layers underlie smaller and ovoid fruit in tomato smaller fruit (sf) mutant. Botany. 2018;96:883–895. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xie C, et al. KOBAS 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W316–W322. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1-S6 and Table S1 and S4