Abstract

The incidence of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) is rising in developed countries. This is driven by an increase in HNSCCs caused by high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infections or HPV+ HNSCCs. Compared to HNSCCs not caused by HPV (HPVc HNSCCs), HPV+ HNSCCs are more responsive to therapy and associated with better oncologic outcomes. As a result, the HPV status of an HNSCC is an important determinant in medical management. One method to determine the HPV status of an HNSCC is increased expression of p16 caused by the HPV E7 oncogene. We identified novel expression changes in HPV+ HNSCCs. A comparison of gene expression among HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs in The Cancer Genome Atlas demonstrated increased DNA repair gene expression in HPV+ HNSCCs. Further, DNA repair gene expression correlated with HNSCC survival. Immunohistochemical analysis of our HNSCC microarray confirmed that DNA repair protein abundance is elevated in HPV+ HNSCCs.

Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are a family of over 200 different viruses that are grouped into five genera (alpha-, beta-, gamma-, mu-, and nu-papillomaviruses) (Bernard et al., 2010). This large family of viruses causes a wide array of maladies by infecting human mucosal and epithelial tissue (Doorbar et al., 2012). The diseases associated with HPV infections range from relatively benign warts to deadly carcinomas (Doorbar et al., 2015). Oncogenicity has been most clearly demonstrated for a subset of the alpha-papillomavirus genus, termed high-risk alpha-papillomaviruses. For simplicity, we refer to high-risk alpha-papillomaviruses as HPVs in this report. HPVs cause nearly all cervical cancers through the expression of two viral oncogenes (HPV E6 and E7) that disrupt tumor suppressor pathways (Bosch et al., 2002). HPV E6 promotes p53 degradation and activates telomerase, while HPV E7 destabilizes Rb (Boyer et al., 1996, p. 53; Dyson et al., 1989; Huibregtse et al., 1991; Münger et al., 1989a, 1989b, p. 6). Both HPV E6 and E7 also manipulate the host DNA repair responses such that viral replication is promoted at the expense of host genome fidelity (Anacker et al., 2016, 2014; Chappell et al., 2015; Gillespie et al., 2012; Hong and Laimins, 2013; Mehta and Laimins, 2018; Wallace, 2020; Wallace and Galloway, 2014).

In addition to their role in cervical cancers, HPVs cause a growing subset of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) (Kobayashi et al., 2018). These HPV positive HNSCCs (HPV+ HNSCCs) are an increasing proportion of malignancies in developed countries (Chaturvedi and Zumsteg, 2018; Marur et al., 2010). This increase is occurring as efforts to combat the abuse of tobacco and alcohol have decreased the number of HNSCCs that are not related to HPV infections (HPV- HNSCCs). There are notable differences in HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs. Clinically, HPV+ HNSCCs are typically less aggressive and more responsive to care (Ang et al., 2010; Ang and Sturgis, 2012). At the molecular level, HPV- HNSCC tend to have p53 mutations, while HPV+ HNSCCs more often have wild type p53 and notably higher p16 abundance (Blons and Laurent-Puig, 2003; Maruyama et al., 2014; Westra et al., 2008).

We hypothesize that HPV oncogenes cause other gene expression differences in HNSCCs. To test this hypothesis and identify host gene changes associated with HPV, we used a combination of computational and standard pathology analyses. This mixed-method approach identified increased expression of DNA repair genes in HPV+ HNSCCs compared to HPV- HNSCCs. More specifically, this examination of a publicly available dataset from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) shows genes from two repair pathways (homologous recombination (HR) and translesion synthesis (TLS)) are more robustly expressed in HPV+ HNSCCs (Cancer Genome Atlas Network, 2015). Differential expression of three of these genes were associated with changes in HNSCC survival. We generated a novel tissue microarray (TMA) of HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs to further probe this relationship. TMA immunohistochemical staining confirmed our in silico data, showing increased DNA repair protein abundance in HPV+ HNSCCs. The most specific increase was seen for the homologous recombination protein, RAD51.

Results

DNA Repair Gene Expression was Increased in HPV positive HNSCCs compared to HPV negative HNSCCs

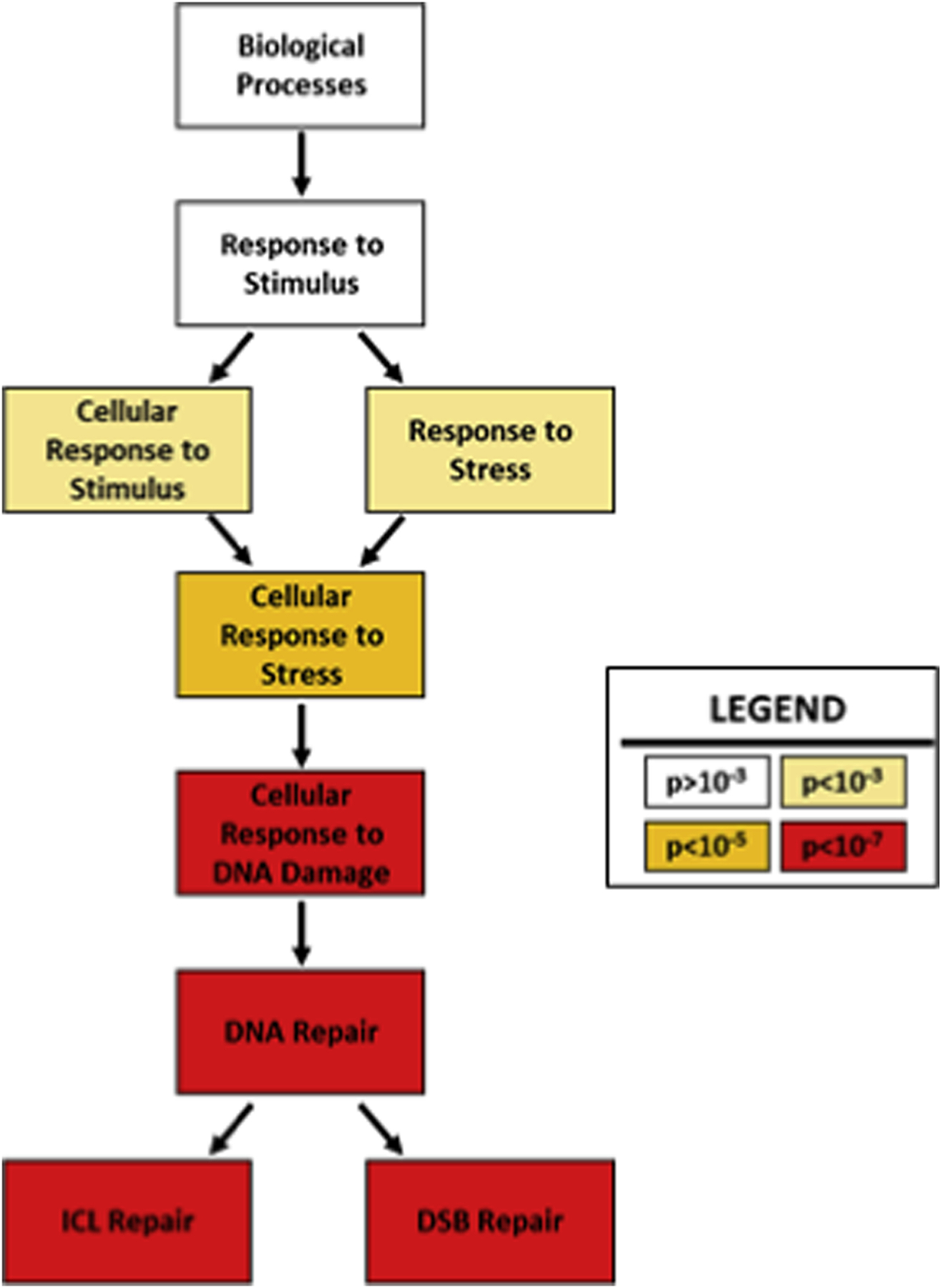

To understand how gene expression differed between HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs, we segregated the TCGA dataset on HNSCCs by the clinical designation of HPV status as originally reported (Cancer Genome Atlas Network, 2015). There were data from 21 HPV+ HNSCCs and 65 HPV- HNSCCs. We ranked genes that were differentially expressed in HPV+ versus HPV- HNSCCs based on the statistical significance of the differences. We then used the Gene Ontology enRIchment anaLysis and visuaLizAtion tool (GOrilla) to determine if these differentially expressed genes were involved in any shared cellular processes (Eden et al., 2009) GOrilla analysis demonstrated that the genes that were differentially expressed in HPV+ versus HPV- HNSCCs were frequently involved in the cellular stress response (Figure 1 and Supplemental Data 1). More specifically, there was a striking enrichment for changes in DNA damage repair (DDR) gene expression (p<10−7).

Figure 1: Gene Ontology Analysis of Differential Gene Expression in HPV+ versus HPV- HNSCCs.

Results for gene ontology (GO) analysis of gene expression differences in HPV+ compared to HPV- HNSCCs. Boxes show cellular functions in hierarchical order, descending from general to specific functions. Darker colors indicate greater statistical significance of enrichment.

These data demonstrate clear differences in DDR gene expression in HNSCCs based on HPV status, but they do not indicate whether repair gene expression is more often higher or lower in HPV+ HNSCCs compared to HPV- HNSCCs. Therefore, we quantified the expression of 137 DDR genes in HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs. DNA repair genes were chosen using unbiased definitions of six established repair pathways (nucleotide excision repair (NER), Fanconi Anemia repair (FA) , base excision repair (BER), TLS, HR and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)) (Alan and D’Andrea, 2010; Bult et al., 2019; Cooper, 2000; Davis and Chen, 2013; Kanehisa and Goto, 2000; Laat et al., 1999; Prakash et al., 2005; Whitaker et al., 2017). The ratio of the expression difference and the significance of these changes was determined for each gene (Figure 2A). This analysis demonstrated that DDR gene expression was commonly increased in HPV+ HNSCCs relative to HPV- HNSCCs. We dissected this data further by defining the frequency of increased gene expression among the DDR pathways. Increased DDR gene expression in HPV+ HNSCCs was evident across all DDR pathways, ranging from 81.8% of NER genes to 100% of the significant changes in TLS and FA genes (Figure 2B).

Figure 2: Differences in DNA Repair Gene Expression Between HPV- and HPV+ HNSCCs.

A. Volcano plot of DNA repair gene expression compared between HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs. Statistical significance is shown on the Y-axis, plotted as the negative log of the p-value. The log ratio of gene expression in HPV+ HNSCCs compared to HPV- HNSCCs are shown on the X-axis. Red circles denote significant changes in expression (p<0.05), while clear dots indicate points below this statistical cutoff. Data points to the left of the Y-axis have decreased expression in HPV+ HNSCCs. Data points to the right of the Y-axis have increased expression in HPV+ HNSCCs. B. Bar graph showing the ratio of differnces in DNA repair gene expression in HNSCCs based on HPV status. Red indicates the percentage of genes with lower expression in HPV+ HNSCCs. Green indicates the percentage of genes with higher expression in HPV+ HNSCCs. Data is shown for genes “overall” and grouped into six pathways (NER=nucleotide excision repair, FA=Fanconi anemia repair, BER=base excision repair, TLS=translesion synthesis, HR=homologous recombination, NHEJ=non-homologous end joining).

Based on these findings and our laboratory’s in vitro studies demonstrating HPV oncogenes manipulation of HR and TLS, we focused our analysis on genes from these two pathways [Wendel et al submitted, 40]. Specifically, we chose four representative TLS genes (PCNA, RAD18, UBE2A and UBE2B) and four representative HR genes (BRCA1, BRCA2, RPA1, RAD51). These analyses included few genes and thus were more amenable to manipulation, so we moved from the clinical definition of HPV status to one defined by molecular signatures and also used in the original report from TCGA (Cancer Genome Atlas Network, 2015). When comparing the expression of these genes, all eight had increased expression in HPV+ HNSCCs (Figure 3A–H). Because the prognosis for HPV+ HNSCCs is significantly better than HPV- HNSCCs, we evaluated whether expression of these eight genes was associated with differences in median survival. For this analysis, we included the complete TCGA dataset (Figure 4). When analyzed together, increased expression of the eight representative TLS and HR genes was not associated with a significant difference in survival (Data Not Shown). However, when analyzed individually, the expression of three of these eight genes was associated changes in survival. Increased expression of two HR genes (BRCA1 and RPA1) was associated with increased HNSCC survival, while increased UBE2A expression correlated with decreased survival (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Expression of Representative Translesion Synthesis and Homologous Recombination Genes is Higher in HPV+ HNSCCs.

Box plots depict the expression of A. BRCA1, B. BRCA2, C. PCNA, D. RAD18, E. RAD51, F. RPA1, G. UBE2A, and H. UBE2B gene expression in HPV+ (red) and HPV- (black) HNSCCs. Expression is plotted as FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon model per million reads mapped), a standard normalization of gene expression based on RNA-seq data found in the TCGA database.

Figure 4: Prognostic Value of DNA Repair Gene Expression in HNSCCs.

Kaplan Meier curves for HNSCCs differentiated by expression of A. BRCA1, B. RPA70, and C. UBE2A. These plots were generated using data from the Cancer Genome Atlas. Patients who had cancers with significantly high expression (z score ≥ 2) are shown in red. All other patients are shown in blue. The dotted black line provides visualization of the median survival calculation. P-values denoting significant difference (log-rank test) in the two populations are indicated along with the population sizes.

Differences in Homologous Recombination and Translesion Synthesis Protein Abundance Were Detected in HNSCCs.

Our data suggested that increased HR and TLS gene expression has the potential to serve as a biomarker for HPV status in HNSCCs. Unfortunately, detecting differences in gene transcripts is not practical clinically. However, immunohistochemical staining (IHC) is frequently used to distinguish tumors from margins and among different types of tumors. This includes the detections of increased p16 levels as a marker of HPV status in HNSCCs. An obvious and preliminary step in developing biomarkers for detection by IHC is confirming that there are detectable differences from control tissue. Based on our computational data, we hypothesized that elevated HR and TLS protein abundance would be detectable by IHC in a subset of HNSCCs. Specifically, we hypothesized that these increases would be seen more often in HPV+ HNSCC. We began testing the first part of our hypothesis by comparing TLS and HR protein abundance in HNSCC and untransformed oral mucosa using the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) (Uhlén et al., 2015, 2005). This resource provided histology data for these tissue that had been scored by independent pathologists. As a positive control, we observed p16 staining (Figure 5). There were detectable differences in p16 between control and transformed oral epithelial cells. P16 abundance was at times higher in HNSCCs than control tissue. However, to our surprise, p16 levels were most often reduced compared to control tissue. Because the HPV status of these samples was undetermined, this could indicate that most HNSCCs in the HPA are HPV negative. We used a housekeeping gene (nucleolin) as a negative control. There was no differential nucleolin staining between transformed or control tissue.

Figure 5: DNA Repair Protein Abundance Varies Among HNSCCs and Compared to Normal Oral Epithelia.

A. Representative IHC staining of DNA repair proteins in untransformed oral epithelia (normal) and HNSCCs (tumors) from the Human Protein Atlas (top). Letters in the lower left of each image indicate the composite score of the tissue shown. (H=High, M=Medium, L=Low) For normal tissue, the representative image corresponds to the knowledge-based annotation provided by Human Protein Atlas. B. The distribution of composite scores compared to control tissue. Red bars denote the percentage of tumors with a composite score lower than control tissue. Black bars denote the percentage of tumors with the same composite score as control tissue. Brown bars denote the percentage of tumors with a composite score higher than control tissue. P16 is included as an established biomarker of HPV status with more than half of its composite scores higher or lower than control tissue. Nucleolin is included as a negative control with composite scores that match control tissue.

Having confirmed the utility of this resource, our next step was to use data contained in the HPA to conduct a preliminary analysis of TLS and HR proteins as biomarkers for HPV status in HNSCCs.

Specifically, our goal was to determine if any of the gene products of BRCA1, RAD18, PCNA, UBE2A/B (RAD6), RAD51 and RPA1 (RPA70) could be detected at higher levels in HNSCCs compared to normal oral mucosa. These data were promising as a proportion of HNSCCs had BRCA1, RAD51, RAD18, and PCNA levels higher than control tissue. Notably, the frequency of their increase was at least as high as the frequency of increased p16 (Figure 5).

While these data were encouraging, the inability to compare repair protein staining levels among HPV+ and HPV- HNSCC represented a significant shortcoming. To address this gap in our analysis, we generated a novel tissue microarray (TMA) to determine if the abundance of these seven representative DDR proteins differed between HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs. The TMA consisted of 27 HPV+ and 9 HPV- HNSCCs. Patient demographic and tumor variables were compared between HPV positive and negative groups (Table 1). Significant differences in mean age existed between groups (58.7 in HPV+, 69.7 in HPV- , p<0.01), consistent with the younger demographic of people with HPV+ HNSCCs (Chaturvedi and Zumsteg, 2018). In addition, HPV+ tumors were more likely to be poorly differentiated, though not statistically significant (p=0.11). This reflects an established tendency for HPV+ tumors to present with de-differentiated histopathology (Dahlstrom et al., 2003). Individuals with HPV- tumors were more likely to be recurrent or previously treated, though again not statistically significant (p=0.06). This was consistent with the recognized tendency for HPV- HNSCCs to recur more frequently (Faraji et al., 2017). No other clinical or tumor characteristics were notably different between groups, including gender, tumor stage, perineural invasion and lymphovascular invasion status.

Table 1: Tumor Microarray Demographic Data.

Patient and tumor characteristics are compared between HPV+ and HPV- HNSCC groups.

| HPV Positive n=26 | HPV Negative n=9 | P= | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean (SD)) | 58.7 (10.1) | 69.7 (9.4) | 0.0069 | |

| Sex(n (%)) | ||||

| Female | 7 (26.9) | 3 (33.3) | ||

| Tumor Site (n (%)) | ||||

| Soft palate | 0(0) | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Perineural Invasion (n (%)) | 5 (19.2) | 1 (11.1) | 1 | |

| Lymphovascular Invasion (n (%)) | 4 (15.4) | 2 (22.2) | 0.6353 | |

| Recurrence/PriorTreatment (n (%)) | 0(0) | 2 (22.2) | 0.0605 | |

| Histologic Grade (n(%)) | 1–2 | |||

| 3–4 | 14 (53.8) | 8 (83.9%) | ||

| T Stage (n (%)) | 1–2 | |||

| 3–4 | 4 (15.4) | 2 (22.2) | ||

We used a composite scoring approach for the analysis of the TMA. This took into account percentage of the tumor stained and the intensity of the staining. Inter-rater reliability between pathologists was excellent with an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.90. Computer assisted analysis was compared to pathologist analysis and demonstrated similar results (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.68). While no differences were seen in four of queried proteins (RPA70, BRCA2, PCNA and RAD18), there was greater IHC staining for two HR proteins, RAD51 and BRCA1 (Figure 6 and Supplemental Figure 1). Mean composite scores in BRCA1 analysis for HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs were 1.04 and 0.63 respectively, which approached significance (p=0.07). Mean composite scores for RAD51 significantly differed between HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs (2.06 and 0.76, respectively, p<0.01, Figure 6).

Figure 6: Immunohistochemical analysis of DNA repair proteins in HPV positive and negative HNSCC.

A. Representative images of tumor sections considered to have weak or strong staining for RAD51 or BRCA1 as indicated. B. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed for seven DNA repair proteins using a tissue microarray derived from 27 HPV positive and nine HPV negative HNSCC specimens. Staining intensity and percentage of nuclear staining were measured to derive composite scores that were compared between groups using Mann-Whitney U-test. P values are indicated for comparisons that approached or exceeded cutoffs for statistically significance. All other comparisons did not approach significance.

Conclusions

The incidence of HPV+ HNSCC is rising rapidly (Chaturvedi and Zumsteg, 2018; Marur et al., 2010). Given the known differences between HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs with respect to their epidemiology, clinical behavior, response to treatment, and prognosis, biomarkers capable of distinguishing between the two types of HNSCCs are useful (Ang et al., 2010; Ang and Sturgis, 2012; Gillison et al., 2008). While direct detection of HPV is an attractive option, it is more expensive than tradition pathologic approaches. This gap in clinical diagnostic tests merits new investigations of expression changes associated with HPV+ HNSCCs. We took a multipronged approach to objectively identify genes that were differentially expressed in HPV+ compared to HPV- HNSCCS. Our computational analysis of the TCGA database demonstrated that the expression of genes involved in DNA repair was higher in HPV+ HNSCCs (Figure 1–3). We also found that expression of three of these genes (UBE2A, BRCA1, and RPA1) significantly correlated with survival (Figure 4). Importantly, increased UBE2A expression was a negative prognostic factor. This indicates that the relationship between DDR gene expression is nuanced and that all repair genes cannot be treated as indirect indicators of HPV status. Our transcriptomic analysis support this assertion as we found UBE2A expression did not significantly differ between HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs. Our analysis of HNSCC tissues from the HPA demonstrated that it was possible to detect differences in DDR protein abundance in HNSCCs compared to control tissue. Moreover, these differences were similar to the differences detected when the same comparison was made using an established biomarker of HPV status, p16 (Figure 5). Generating a TMA with HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs allowed us to show that increased repair gene transcripts translated to increased protein that was detectable by IHC (Figure 6). In summary, we found that DDR gene expression in HPV+ HNSCC was similar to the alterations observed with tissue culture systems (Wallace, 2020; Wallace and Galloway, 2014). Further, these results are similar with another recent effort to understand if DNA repair protein abundance mirrored HPV status in HNSCCs (Kono et al., 2020). This supports the value and validity of in vitro characterization of HPV oncogene biology.

Currently, p16 is used as a surrogate marker of HPV in HNSCCs (Liang et al., 2012). p16 levels are higher in HPV+ HNSCCs and much of the biology driving this change is understood. HPV E7 deregulates the cell cycle by disrupting Rb-E2F complexes (Dyson et al., 1989, p. 7). This causes replication stress and increased p16 expression. As a surrogate marker of HPV, p16 is notably sensitive. However, p16 is also influenced by stimuli other than HPV E7 (e.g., B-RAF activation) (Mackiewicz-Wysocka et al., 2017). Because differences in RAD51 abundance between HPV+ and HPV- are detectable by IHC, changes in RAD51 (and potentially other DDR protein levels) may be able to complement existing biomarkers. For instance, combining p16 with RAD51 could decrease the risk of false positives and more accurately triage HNSCCs by HPV status.

Expression of UBE2A, BRCA1 and RPA1 each significantly correlated with HNSCC survival. HPV oncogenes cause increased expression of both BRCA1 and RPA1 in cell culture systems (Wallace et al., 2017). This observation combined with the positive prognostic value of their expression suggests that they may also be acting as surrogate markers of HPV status. Our TMA data support this position. It is more difficult to explain the correlation of increased UBE2A expression with decreased survival. UBE2A expression did not significantly vary between HPV- and HPV+ HNSCCs. An attractive explanation is that high UBE2A expression promotes Cisplatin resistance. Both HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs are frequently treated with the drug and UBE2A is an essential component of TLS, a pathway that promotes Cisplatin resistance when over-activated (Albertella et al., 2005; Srivastava et al., 2015).

In summary, our data support the development of TLS and HR proteins as biomarkers of HPV status in HNSCCs. However, they also require further investigation and substantiation. Our future studies will focus on the expansion of our TMA. While the data presented here is interesting, expanding our TMA to include additional HPV+ and HPV- HNSCC samples as well as non-tumor control tissues would be an improvement. Further, determining HPV status by more definitive methods than p16 would also improve our analysis.

Materials and Methods:

Human Protein Atlas:

Representative IHC and staining information was obtained from the HPA (Uhlén et al., 2005). Composite gene marker IHC scores were determined by evaluating staining intensity and frequency. These were then converted to categories corresponding to the knowledge-based annotation used by the HPA for control tissue.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Analysis:

HNSCC TCGA data were analyzed to define mRNA expression (Uhlén et al., 2015, 2005). Expression levels were normalized to control tissues. For the analysis found in Figures 1 and 2, HPV status was based on clinical criteria as reported to TCGA. To be considered “clinically positive” for HPV, the tumor had to be located in an oropharyngeal subsite and be accompanied by a positive assay for HPV that was reported in the electronic case report. Tumors where HPV status were not determined excluded from this analysis.

For the analysis of gene expression found in Figure 3, the HPV status was based on molecular signatures that include microRNA, DNA methylation, gene expression (cellular and viral) as reported in TCGA manuscript (Cancer Genome Atlas Network, 2015). These approaches are similar, but identical to more recent efforts to analyze HPV status in HNSCCs (Johnson et al., 2018; Pérez Sayáns et al., 2019)

The web-based analysis tools at www.cbioportal.com were used to examine RNAseq data from these tumors (Cerami et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013).

Protein and Gene Designations:

When the gene and protein names differ, we show both in this format: GENE (PROTEIN).

Tissue Microarray Creation:

De-identified archival formalin fixed, paraffin embedded patient tissue was obtained from the University of Kansas Medical Center, Biospecimen Repository Core Facility using an Institutional Review Board approved protocol. p16 IHC served as a marker of HPV positive samples. Tumors were considered p16 positive when there was strong and diffuse staining in at least 75% of tumor cells. Surgical specimens from HPV+ and HPV- HNSCCs were selected. Thirty-six total specimens were included in the TMA (27 HPV+ and nine HPV- specimens). Representative areas were marked on hematoxylin and eosin stained slides by a board certified pathologist for use. Using the marked slide as a map, two-millimeter thick core punches were taken from the corresponding donor paraffin block and transferred to a recipient paraffin block using the TMArrayer instrument (Pathology Devices). The block containing unique donor cores were sectioned at 4um, mounted on adhesive slides, and dried prior to staining procedures.

Immunohistochemistry:

Slides were baked at 60°C for one hour. After deparaffinization and rehydration, tissue sections were treated with either citrate buffer or Borg Decloaker for five minutes in a pressure cooker for antigen retrieval. Hydrogen peroxide (3%) was applied to the sections for 10 minutes. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies against BRCA1 (Biocare Medical), BRCA2 (Proteintech), PCNA, RAD51 (Abcam), RAD6, RAD18 or RPA1/RPA70 (Abcam) for 30 minutes. After buffer rinsing, sections were incubated with anti-mouse HRP-labeled polymer (EnVision) or anti-HRP-labeled polymer (Mach2) for 30 minutes and buffer rinsed twice. Finally, the staining was visualized by DAB+ (Dako). IHC staining was performed using the IntelliPATH FLX Automated Stainer at room temperature.

A light hematoxylin counterstain was performed, then slides were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted using permanent mounting media.

Immunohistochemical Analysis:

TMA slides were analyzed independently by two board-certified pathologists who were blinded to the sample’s HPV status. Tumors were scored for intensity of staining on a scale of zero to four and on the percentage of tumor cells that were positive. A composite score between zero and four was derived by multiplying the intensity by percent staining. Aperio ImageScope (Version 12.3.0) was used for a secondary computer-based analysis to validate pathologist’s assessments. An algorithm was created within the program to capture staining intensity and percentage. This was optimized for accuracy on a series of sample slides.

Clinical Data Analysis:

De-identified clinical data were received from the University of Kansas Medical Center’s Biospecimen Repository Core Facility. Age was provided in five-year ranges and the median range was used for data analysis.

Statistical Analysis:

SPSS software was used for statistical analyses of the TMA (version 22; IBM Corp). Fishers Exact and Analysis of Variance tests were applied to categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U tests were applied to continuous variables. Significance was only reported for p-values <0.05. Kaplan-Meier curves display survival data, and the logrank test assessed survival differences. TCGA data were analyzed using the analysis tools at www.cbioportal.org (Cerami et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013).

Pathway and Gene Ontology Analysis:

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes and The Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) were used to identify gene subsets specific to the following pathways: TLS, HR, NER, FA, BER, NHEJ (Bult et al., 2019; Kanehisa and Goto, 2000). MGI was used to define genes in the translesion synthesis pathway because this pathway was not included in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. We compared differences in gene expression between HPV+ and HPV- HNSCC tumors and used p-value data to rank genes. Gene ontology analysis of this ranked list was conducted using the Gene Ontology enrichment anaLysisand visualizAtion (GOrilla) online tool. A threshold of p<10−5 was chosen.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Representative image of TMA slide stained with antibodies against BRCA1.

Supplemental Data 1: List of enriched processes identified by GOrilla analysis of genes that differentially in HPV+ HNSCCs compared to HPV- HNSCCs that have a p-value less than 1x10−9. FDR denotes thelikelihood of false discovery or the false discovery rate expressed as a q-value.

Highlights.

-Computational analyses show significant differences in DNA repair gene expression in HPV+ HNSCCs versus HPV- HNSCCs.

-Rad51 staining by immunohistochemistry was significantly stronger in HPV+ versus HPV- HNSCCs.

- DNA repair gene expression was positively (BRCA1 and RPA70) and negatively (UBE2A) correlated HNSCC survival.

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge the University of Kansas (KU) Cancer Center’s Biospecimen Repository Core Facility for helping obtain human specimens. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P20-GM103418; YS and NAW and R01 CA227838; SMT), and the University of Kansas Cancer Center (CCSG P30CA168524; SMT).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests related to the work described in our manuscript.

References:

- Alan D, D’Andrea MD, 2010. The Fanconi Anemia and Breast Cancer Susceptibility Pathways. N Engl J Med 362, 1909–1919. 10.1056/NEJMra0809889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertella MR, Green CM, Lehmann AR, O’Connor MJ, 2005. A Role for Polymerase η in the Cellular Tolerance to Cisplatin-Induced Damage. Cancer Res 65, 9799–9806. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anacker DC, Aloor HL, Shepard CN, Lenzi GM, Johnson BA, Kim B, Moody CA, 2016. HPV31 Utilizes the ATR-Chk1 Pathway to Maintain Elevated RRM2 Levels and a Replication-Competent Environment in Differentiating Keratinocytes. Virology 499, 383–396. 10.1016/j.virol.2016.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anacker DC, Gautam D, Gillespie KA, Chappell WH, Moody CA, 2014. Productive replication of human papillomavirus 31 requires DNA repair factor Nbs1. J. Virol 88, 8528–8544. 10.1128/JVI.00517-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tân PF, Westra WH, Chung CH, Jordan RC, Lu C, Kim H, Axelrod R, Silverman CC, Redmond KP, Gillison ML, 2010. Human Papillomavirus and Survival of Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer. N Engl J Med 363, 24–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang KK, Sturgis EM, 2012. Human papillomavirus as a marker of the natural history and response to therapy of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Semin Radiat Oncol 22, 128–142. 10.1016/j.semradonc.2011.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard H-U, Burk RD, Chen Z, van Doorslaer K, Hausen H. zur, de Villiers E-M, 2010. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology 401, 70–79. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blons H, Laurent-Puig P, 2003. TP53 and head and neck neoplasms. Hum. Mutat 21, 252–257. 10.1002/humu.10171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Muñoz N, Meijer CJLM, Shah KV, 2002. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol 55, 244–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer SN, Wazer DE, Band V, 1996. E7 Protein of Human Papilloma Virus-16 Induces Degradation of Retinoblastoma Protein through the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway. Cancer Res 56, 4620–4624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bult CJ, Blake JA, Smith CL, Kadin JA, Richardson JE, Mouse Genome Database Group, 2019. Mouse Genome Database (MGD) 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D801– D806. 10.1093/nar/gky1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network, 2015. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature 517, 576–582. 10.1038/nature14129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N, 2012. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data. Cancer Discov 2, 401–404. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell WH, Gautam D, Ok ST, Johnson BA, Anacker DC, Moody CA, 2015. Homologous Recombination Repair Factors Rad51 and BRCA1 Are Necessary for Productive Replication of Human Papillomavirus 31. J. Virol 90, 2639–2652. 10.1128/JVI.02495-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi AK, Zumsteg ZS, 2018. A snapshot of the evolving epidemiology of oropharynx cancers. Cancer 124, 2893–2896. 10.1002/cncr.31383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GM, 2000. Recombination Between Homologous DNA Sequences. Dahlstrom KR, Adler-Storthz K, Etzel CJ, Liu Z, Dillon L, El-Naggar AK, Spitz MR, Schiller JT, Wei Q, Sturgis EM, 2003 Human Papillomavirus Type 16 Infection and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck in Never-Smokers: A Matched Pair Analysis. Clin Cancer Res 9, 2620–2626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AJ, Chen DJ, 2013DNA double strand break repair via non-homologous end-joining. Transl Cancer Res 2, 130–143. 10.3978/j.issn.2218-676X.2013.04.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorbar J, Egawa N, Griffin H, Kranjec C, Murakami I, 2015Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev. Med. Virol 25, 2–23. 10.1002/rmv.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorbar J, Quint W, Banks L, Bravo IG, Stoler M, Broker TR, Stanley MA, 2012. The biology and life-cycle of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine 30 Suppl 5, F55–70. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson N, Howley PM, Münger K, Harlow E, 1989. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science 243, 934–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden E, Navon R, Steinfeld I, Lipson D, Yakhini Z, 2009. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 48 10.1186/1471-2105-10-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraji F, Eisele DW, Fakhry C, 2017. Emerging insights into recurrent and metastatic human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 2, 10–18. 10.1002/lio2.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N, 2013. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 6, pl1. 10.1126/scisignal.2004088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie KA, Mehta KP, Laimins LA, Moody CA, 2012. Human papillomaviruses recruit cellular DNA repair and homologous recombination factors to viral replication centers. J. Virol 86, 9520–9526. 10.1128/JVI.00247-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillison ML, D’Souza G, Westra W, Sugar E, Xiao W, Begum S, Viscidi R, 2008. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 100, 407– 420. 10.1093/jnci/djn025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Laimins LA, 2013. The JAK-STAT transcriptional regulator, STAT-5, activates the ATM DNA damage pathway to induce HPV 31 genome amplification upon epithelial differentiation. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003295 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huibregtse JM, Scheffner M, Howley PM, 1991. A cellular protein mediates association of p53 with the E6 oncoprotein of human papillomavirus types 16 or 18. EMBO J. 10, 4129–4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME, Cantalupo PG, Pipas JM, 2018. Identification of Head and Neck Cancer Subtypes Based on Human Papillomavirus Presence and E2F-Regulated Gene Expression. mSphere 3 10.1128/mSphere.00580-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S, 2000. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 28, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Hisamatsu K, Suzui N, Hara A, Tomita H, Miyazaki T, 2018. A Review of HPV-Related Head and Neck Cancer. Journal of Clinical Medicine 7, 241 10.3390/jcm7090241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono T, Hoover P, Poropatich K, Paunesku T, Mittal BB, Samant S, Laimins LA, 2020. Activation of DNA damage repair factors in HPV positive oropharyngeal cancers. Virology 547, 27–34. 10.1016/j.virol.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laat W.L. de, Jaspers NGJ, Hoeijmakers JHJ, 1999. Molecular mechanism of nucleotide excision repair. Genes Dev. 13, 768–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Marsit CJ, McClean MD, Nelson HH, Christensen BC, Haddad RI, Clark JR, Wein RO, Grillone GA, Houseman EA, Halec G, Waterboer T, Pawlita M, Krane JF, Kelsey KT, 2012. Biomarkers of HPV in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res 72, 5004–5013. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackiewicz-Wysocka M, Czerwińska P, Filas V, Bogajewska E, Kubicka A, Przybyła A, Dondajewska E, Kolenda T, Marszałek A, Mackiewicz A, 2017. Oncogenic BRAF mutations and p16 expression in melanocytic nevi and melanoma in the Polish population. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 34, 490–498. 10.5114/ada.2017.71119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marur S, D’Souza G, Westra WH, Forastiere AA, 2010. HPV-associated head and neck cancer: a virus-related cancer epidemic. Lancet Oncol. 11, 781–789. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70017-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama H, Yasui T, Ishikawa-Fujiwara T, Morii E, Yamamoto Y, Yoshii T, Takenaka Y, Nakahara S, Todo T, Hongyo T, Inohara H, 2014. Human papillomavirus and p53 mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma among Japanese population. Cancer Sci. 105, 409–417. 10.1111/cas.12369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta K, Laimins L, 2018. Human Papillomaviruses Preferentially Recruit DNA Repair Factors to Viral Genomes for Rapid Repair and Amplification. mBio 9, e00064–18. 10.1128/mBio.00064-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münger K, Werness BA, Dyson N, Phelps WC, Harlow E, Howley PM, 1989a. Complex formation of human papillomavirus E7 proteins with the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product. EMBO J 8, 4099–4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münger K, Werness BA, Dyson N, Phelps WC, Harlow E, Howley PM, 1989b. Complex formation of human papillomavirus E7 proteins with the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product. EMBO J 8, 4099–4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Sayáns M, Chamorro Petronacci CM, Lorenzo Pouso AI, Padín Iruegas E, Blanco Carrión A, Suárez Peñaranda JM, García García A, 2019. Comprehensive Genomic Review of TCGA Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas (HNSCC). J Clin Med 8 10.3390/jcm8111896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S, Johnson RE, Prakash L, 2005. Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: specificity of structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biochem 74, 317–353. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Han C, Zhao R, Cui T, Dai Y, Mao C, Zhao W, Zhang X, Yu J, Wang Q-E, 2015. Enhanced expression of DNA polymerase eta contributes to cisplatin resistance of ovarian cancer stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 112, 4411–4416. 10.1073/pnas.1421365112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlén M, Björling E, Agaton C, Szigyarto CA-K, Amini B, Andersen E, Andersson A-C, Angelidou P, Asplund A, Asplund C, Berglund L, Bergström K, Brumer H, Cerjan D, Ekström M, Elobeid A, Eriksson C, Fagerberg L, Falk R, Fall J, Forsberg M, Björklund MG, Gumbel K, Halimi A, Hallin I, Hamsten C, Hansson M, Hedhammar M, Hercules G, Kampf C, Larsson K, Lindskog M, Lodewyckx W, Lund J, Lundeberg J, Magnusson K, Malm E, Nilsson P, Odling J, Oksvold P, Olsson I, Oster E, Ottosson J, Paavilainen L, Persson A, Rimini R, Rockberg J, Runeson M, Sivertsson A, Sköllermo A, Steen J, Stenvall M, Sterky F, Strömberg S, Sundberg M, Tegel H, Tourle S, Wahlund E, Waldén A, Wan J, Wernérus H, Westberg J, Wester K, Wrethagen U, Xu LL, Hober S, Pontén F, 2005. A human protein atlas for normal and cancer tissues based on antibody proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics 4, 1920–1932. 10.1074/mcp.M500279-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA-K, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist P-H, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Pontén F, 2015. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1260419 10.1126/science.1260419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace NA,2020. Catching HPV in the Homologous Recombination Cookie Jar. Trends Microbiol. 28, 191–201. 10.1016/j.tim.2019.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace NA, Galloway DA, 2014. Manipulation of cellular DNA damage repair machinery facilitates propagation of human papillomaviruses. Semin. Cancer Biol 26, 30–42. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace NA, Khanal S, Robinson KL, Wendel SO, Messer JJ, Galloway DA, 2017. High Risk Alpha Papillomavirus Oncogenes Impair the Homologous Recombination Pathway. J. Virol. JVI 01084–17. 10.1128/JVI.01084-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra WH, Taube JM, Poeta ML, Begum S, Sidransky D, Koch WM, 2008. Inverse relationship between human papillomavirus-16 infection and disruptive p53 gene mutations in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin. Cancer Res 14, 366– 369. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker AM, Schaich MA, Smith MS, Flynn TS, Freudenthal Bret.D., 2017. Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage: from mechanism to disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 22, 1493–1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Chen Y, Liu X, Chu P, Loria S, Wang Y, Yen Y, Chou K-M, 2013. Expression of DNA Translesion Synthesis Polymerase η in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer Predicts Resistance to Gemcitabine and Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy. PLOS ONE 8, e83978 10.1371/journal.pone.0083978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Representative image of TMA slide stained with antibodies against BRCA1.

Supplemental Data 1: List of enriched processes identified by GOrilla analysis of genes that differentially in HPV+ HNSCCs compared to HPV- HNSCCs that have a p-value less than 1x10−9. FDR denotes thelikelihood of false discovery or the false discovery rate expressed as a q-value.