Abstract

Background

Papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is the most common histological type of thyroid cancer. Most PTC patients have favorable outcomes, but 10% of patients still have distant metastases at presentation or during follow-up. Dynamin 2 (DNM2) is the only DNM ubiquitously expressed in human tissues, but its expression and clinical significance in PTC is still unknown.

Material/Methods

In our study, we investigated the expression of DNM2 in 112 cases of PTC and classified the patients into low and high expression of DNM2. The clinical significance of DNM2 was evaluated by assessing its correlation with the clinicopathological parameters with the chi-square method. The correlations between DNM2 expression and the disease-free survival rate or overall survival rate were assessed with the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. The independent prognostic factors of PTC were determined by the Cox-regression hazard model.

Results

Patients with low and high DNM2 expression accounted for 75% and 25% respectively in the 112 patients with PTC. High DNM2 expression was significantly associated with recurrence (P=0.014) and poor prognosis (P=0.004). In addition to tumor stage, DNM2 expression was an independent prognostic biomarker of PTC, indicating an unfavorable prognosis.

Conclusions

DNM2 was an independent PTC biomarker indicating more likely recurrence and poorer prognosis. Detecting DNM2 expression may help to select the high-risk patients for adjuvant therapy.

MeSH Keywords: Biological Markers, Dynamin II, Prognosis, Recurrence, Thyroid Neoplasms

Background

Thyroid cancer (TC) is the most common endocrine cancer worldwide, with 298 000 cases diagnosed globally [1]. There were about 57 000 new cases in the United States in 2015 [2]. New cases of TC only account for 2.1% of all cancer types, but the morbidity of TC has increased worldwide during the past decades. Histologically, TC can be classified into papillary TC (PTC), follicular TC, medullary TC, poorly differentiated TC, and Hurthle cell and anaplastic TC [3]. PTC accounts for more than 85% of all TC types [4]. The prognosis of differentiated TC is usually favorable. However, the mortality of TC remains stable, and has even increased in some studies in past years, which is confusing because the treatment equipment and drugs have improved dramatically [5,6]. Approximately 10% of patients with PTC have distant metastases at presentation or during follow-up [7]. Therefore, the exploration of new biomarkers and the knowledge of new characteristics of TC should be continuously updated.

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) is one of the major pathways to uptake and recycling of membrane receptors and ligands, and it is essential in cell–cell communication and cell–substrate interactions [8]. Besides the functions in neuron or endocrine cells, CME was also reported to influence tumor progression via promoting recycling and endocytosis of membrane receptors such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [9]. In the process of CME, dynamins (DNMs) gather around the necks of clathrin-coated pits and facilitate membrane fission [10]. DNM is not only the first protein proposed to catalyze membrane fission, but is also a key effector in physiological functions including endocytosis, membrane fusion, and synaptic transmission [11]. DNM is a kind of highly conserved guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) composed of the GTPase domain, and it is widely expressed in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes [11]. In humans, the DNM family has 3 isoforms, DNMs 1, 2, and 3, that have different tissue specificities and expressing spectra [12]. In addition to functions in secretion and endocytosis, emerging evidence supports a promoting function of DNM in tumorigenesis. Previous studies demonstrated that DNM may be involved in different processes of tumor progression such as motility, invasion, and metastasis [13]. However, whether DNM functions in PTC progression and prognosis is still unknown.

In this study, we investigated the expression of DNM2 in 112 cases of PTC and classified the patients into low and high expression of DNM2. Moreover, we evaluated the significance of DNM2 by analyzing its correlation with clinicopathological parameters, disease-free survival (DFS) rate, and overall survival (OS) rate.

Material and Methods

Patients and tissue samples

In our study, a total of 323 consecutive patients, the inception cohort, was diagnosed with TC and underwent radical surgery in YIDU Central Hospital and the Central Hospital affiliated with Shandong 1st Medical University from 2000 to 2010. The validation cohort was selected from the primary cohort, consisting of 112 patients who (1) had systemic follow-ups, (2) received no adjuvant therapy before tumor recurrence, and (3) were diagnosed with PTC. The validation cohort comprised 41 male patients and 71 female patients. The average follow-up time was 60.3 months and the median follow-up was 55 months. The pathological stage of PTC was classified with 7th tumor-nodes-metastases (TNM) American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. The OS time was defined as the time between operation and the death time or last follow-up, and the DFS time was defined as the time from operation to recurrence confirmed by imaging examination such as ultrasound. All the specimens were obtained with the written consent of the patients and handled anonymously according to ethical standards. The whole investigation was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Central Hospital affiliated with Shandong 1st Medical University, as well as YIDU Central Hospital.

Tissue microarray (TMA)

Representative paraffin-embedded sections of PTC were constructed as in a previous study [14]. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of slides was carried out to select the staining area of all samples. Tissue columns as wide as 1.0 mm were taken from each sample for TMA slides.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC was carried out to investigate the expression of DNM2 using the streptavidin–peroxidase complex method according to previous studies [15,16]. The formalin-fixed specimens were deparaffinized and rehydrated with xylene and graded alcohol first. After that, endogenous peroxidase was inactivated by incubation in 3% H2O2 for 20 min and slides were immersed in boiled citrate buffer for 10 min for antigen retrieval. After incubation in 5% bovine serum albumin, the specimens were incubated in DNM2 antibody (ab3457, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). After rinsing with phosphate-buffered saline three times, the corresponding secondary antibody (Sangon, Shanghai, China) was used to incubate slides at room temperature for 1 h. Streptavidin-peroxidase complex reagent and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine solution (Sangon) were applied to stain the antigen. Hematoxylin was finally applied to counterstain the slides.

IHC score system

IHC results were quantified by the IHC score as in a previous study [17]. After IHC staining, stained TMAs were screened with a TMA scanner (Pannoramic MIDI; 3D HISTECH, Budapest, Hungary), and the tumor area was selected by a pathologist who was unaware of the clinical information. The IHC score of the staining tumor area was quantified by Quant Center software. Staining intensity was mechanically defined as weak, moderate, or strong by the software, and the final IHC score was calculated as follows: IHC score=(percentage of cells of weak intensity×1)+(percentage of cells of moderate intensity×2)+(percentage of cells of strong intensity×3) in the Quant Center software [18,19]. The final IHC scores were confirmed by independent senior pathologists in case of the wrong selection of tumor area. The overall cohort was classified into different groups with a cutoff that was defined as the point in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves with the highest sum of specificity plus sensitivity [20]. In this study, the DNM2 cutoff was 60.0, meaning that scores higher than 60.0 were set as the high DNM2 expression.

Statistical analysis

All the data and statistical significances were analyzed by SPSS22.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The chi-square method was used to analyze the correlations between DNM2 expression and other clinicopathological factors. The Kaplan-Meier method was applied to evaluate the correlation between DNM2 and OS curve or DFS curve. The log-rank test was used to calculate the statistical significance between subgroups. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was applied to confirm the independent prognostic factors. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Basic information of PTC patients

Our validation cohort consisted of 112 patients, 41 male and 71 female, diagnosed with PTC and who underwent radical surgery. Among them, elder patients (more than 45 years old) took up the majority of the cohorts (81 cases, 72.32%). In our study, 21 cases (18.75%) had more than one tumor, and 22 patients (19.64%) had PTC of both lobes. During the follow-up, 47 patients had tumor recurrence, accounting for 41.96%.

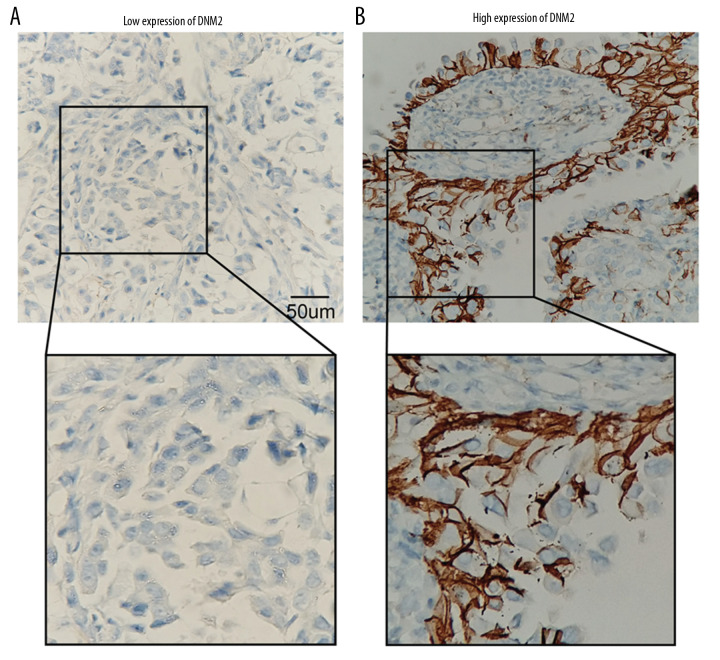

Expression of DNM2 in PTC

The expression of DNM2 in the 112 patients was investigated with IHC. According to the cutoff score, the overall cohort was divided into patients with low and high DNM expression, accounting for 75% and 25%, respectively. In our study, DNM2 was mainly observed in the cell membrane, although the cytoplasm also had slight staining (Figure 1A, 1B). This was consistent with the function of DNM2 as a master modulator of vesicle endocytosis.

Figure 1.

Expression of dynamin 2 (DNM2) in papillary thyroid cancer (PTC). Expression of DNM2 was investigated in 112 cases of PTC; patients were classified into low (A) and high (B) expression. The immunohistochemistry scores of (A) and (B) were 15.2 and 132.4, respectively.

Correlation between DNM2 and clinicopathological factors

The correlations between DNM2 and the clinicopathological factors were evaluated with the chi-square test to further investigate the clinical significance of DNM2 (Table 1). The basic clinicopathological factors included the gender and age of patients; tumor size number, differentiation, and site; and T, N, and TNM stage. However, there was no variable significantly associated with DNM2 expression.

Table 1.

Correlation between clinicopathological characters and dynamin 2 (DNM2) expression.

| Variables | DNM2 | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 32 | 9 | 0.654 |

| Female | 52 | 19 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| <45 | 22 | 9 | 0.627 |

| ≥45 | 62 | 19 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| ≤2 | 31 | 10 | 1.000 |

| >2 | 53 | 18 | |

| Tumor number | |||

| Single | 68 | 23 | 0.889 |

| Multiple | 16 | 5 | |

| Differentiation | |||

| Good | 46 | 13 | 0.444 |

| Moderate | 38 | 15 | |

| Site | |||

| Left/right | 68 | 22 | 0.784 |

| Left+right | 16 | 6 | |

| T stage | |||

| I+II | 78 | 24 | 0.251 |

| III+IV | 6 | 4 | |

| N stage | |||

| N0 | 55 | 18 | 0.909 |

| N1 | 29 | 10 | |

| TNM stage | |||

| I+II | 63 | 20 | 0.709 |

| III+IV | 21 | 8 | |

Calculated by the chi-square test.

TNM – tumor-node-metastasis.

DNM2 correlated with the recurrence of PTC

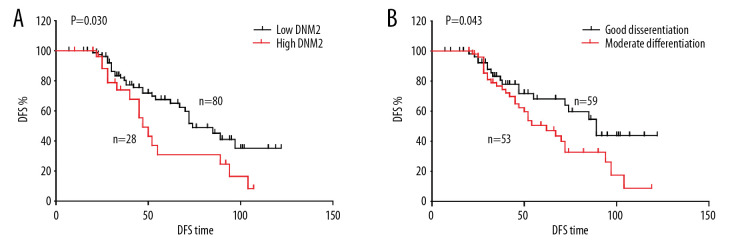

Although most patients with PTC had a favorable prognosis, a proportion of patients still had a recurrence or even tumor progression after surgery. Tumor recurrence is still a big problem in PTC. Here we investigated the correlation between recurrence and clinical factors including DNM2 expression (Table 2). The DFS curves of different variables were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the statistical differences were calculated with the log-rank test. In our test, high DNM2 significantly correlated with tumor recurrence (P=0.014; Figure 2A), indicating that patients with high DNM2 expression were more vulnerable to tumor recurrence compared with those with low DNM2, with DFS time 74.0 and 134.4 months, respectively. In addition, moderate differentiation was also an influencing factor of likely recurrence. The average DFS time of good and moderate differentiation was 143.5 and 85.7 months, respectively (Figure 2B).

Table 2.

Correlation between disease-free survival (DFS) and clinicopathological factors.

| Variables | DFS time | P* |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 63.3 | 0.711 |

| Female | 55.3 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| <45 | 60.3 | 0.177 |

| ≥45 | 54.0 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||

| ≤2 | 57.0 | 0.608 |

| >2 | 52.3 | |

| Tumor number | ||

| Single | 65.1 | 0.576 |

| Multiple | 56.9 | |

| Differentiation | ||

| Good | 68.2 | 0.043 |

| Moderate | 50.5 | |

| Site | ||

| Left/right | 72.1 | 0.814 |

| Left+right | 54.9 | |

| T stage | ||

| I+II | 60.4 | 0.700 |

| III+IV | 46.9 | |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 58.8 | 0.773 |

| N1 | 58.9 | |

| TNM stage | ||

| I+II | 58.3 | 0.924 |

| III+IV | 60.8 | |

| Dynamin 2 | ||

| Low | 30.8 | 0.030 |

| High | 67.6 | |

Calculated by the log-rank test.

TNM – tumor-node-metastasis.

Figure 2.

Correlation among disease-free survival (DFS), dynamin 2 (DNM2) expression, and differentiation. The DFS curves of DNM2 expression (A) and differentiation (B) were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the statistical differences were calculated with the log-rank test.

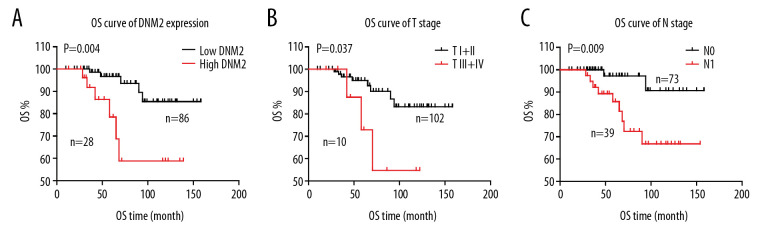

DNM2 was an independent prognostic factor of PTC

The correlations between the OS rate and all the clinicopathological factors were also investigated using univariate analysis, and the statistical significances were assessed by the log-rank test (Table 3). In our study, DNM2 expression was highly correlated with the OS rate of PTC (P=0.004; Figure 3A). High DNM2 expression indicated more unfavorable prognoses of PTC. In addition to DNM2, advanced T stage (P=0.037) and TNM stage (P=0.009) were also substantially relevant to the OS rate of PTC (Figure 3B, 3C). Moreover, advanced TNM stage tended to be related to poor prognosis, with an unobvious statistical significance (P=0.060).

Table 3.

Prognostic value of dynamin 2 (DNM2) and other clinicopathological factors were evaluated by univariate and multivariate analyses.

| Variables | 5-year OS | P* | HR | 95% CI | P** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 89.0 | 0.380 | |||

| Female | 86.6 | ||||

| Age | |||||

| <45 | 88.3 | 0.438 | |||

| ≥45 | 93.7 | ||||

| Tumor size (cm) | |||||

| ≤2 | 91.4 | 0.905 | |||

| >2 | 92.3 | ||||

| Tumor number | |||||

| Single | 92.7 | 0.681 | |||

| Multiple | 92.3 | ||||

| Differentiation | |||||

| Good | 92.4 | 0.105 | 1 | ||

| Moderate | 92.6 | 1.43 | 0.32–6.34 | 0.636 | |

| Site | |||||

| Left or right | 92.6 | 0.674 | |||

| Left+right | 91.7 | ||||

| T stage | |||||

| I+II | 95.0 | 0.037 | 1 | ||

| III+IV | 72.9 | 1.31 | 0.30–5.67 | 0.720 | |

| N stage | |||||

| N0 | 90.7 | 0.009 | 1 | ||

| N1 | 85.7 | 5.87 | 1.26–27.2 | 0.024 | |

| TNM stage | |||||

| I+II | 93.7 | 0.060 | |||

| III+IV | 88.4 | ||||

| DNM2 | |||||

| Low | 96.7 | 0.004 | 1 | ||

| High | 78.5 | 4.82 | 1.46–15.92 | 0.010 | |

Calculated by the log-rank test in univariate analysis;

calculated by the Cox-regression hazard model in multivariate analysis.

OS – overall survival; HR – hazard ratio; CI – confidence interval; TNM – tumor-node-metastasis.

Figure 3.

Correlation among overall survival (OS), dynamin 2 (DNM2) expression, tumor (T) stage, and node (N) stage. The OS curves of DNM2 expression (A), T stage (B), and N stage (C) were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the statistical differences were calculated with the log-rank test.

The prognostic factors verified by the univariate analysis were enrolled into the Cox-regression hazard model for multivariate analysis (Table 3). In our test, DNM2 was determined as an independent prognostic biomarker of PTC (hazard ratio [HR]=4.82, HR=1.46–15.92, P=0.010) by multivariate analysis. Moreover, N stage was also verified as an independent prognostic factor in PTC (HR=5.87, HR=1.26–27.2, P=0.024).

Discussion

About 10% of PTC patients have distant metastases at presentation or after treatment such as surgery [7]. Lungs and bones are the most vulnerable organs to metastasis. Only a portion of patients can be treated with curative methods (e.g. surgery); most patients receive systemic treatment [21,22]. The targeted therapy is a great breakthrough to treat advanced TC. More than 70% of PTCs harbor pathogenic mutations such as BRAF, RAS, and RET/PTC rearrangement [23]. Although various helpful biomarkers were discovered to predict recurrence and prognosis in PTC [24–27], the target therapy of PTC is still very limited. To date, the approved targeted drugs for PTC are mainly antiangiogenic drugs such as sorafenib and lenvatinib. Besides the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, clinical studies on suppressing mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling have also been ongoing [28]. The translational medicine of PTC biomarkers and targeted therapy has made slow progress in recent years. One possible reason is that patients with PTC usually have a favorable outcome, and the long-term follow-ups are more difficult than short-term ones. In our study, we constructed a cohort with follow-up as long as 158 months, showing the character of PTC recurrence and prognosis by which we defined DNM2 as an independent prognostic biomarker. Our results help to select high-risk patients for adjuvant therapy after surgery by detecting expression of DNM2. Moreover, our findings that DNM2 led to more likely recurrence and poorer prognosis has great value for clinical application because inhibitors of DNM2, such as Dynasore, have good cell permeability and specificity [29]. Our results implied that Dynasore may be a viable drug for PTC considering that DNM2 was a potential target. Of course, many more experiments are needed to prove this.

Emerging evidence showed that DNM was implicated in tumorigenesis and other characters of tumor progression. DNM was suggested to regulate tumor cell endocytosis, motility, drug resistance, or metastasis [13] in a series of cancer types including breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and ovarian cancer [30–32]. Moreover, one important interacting protein of DNM, DNM-related protein 1, has been widely involved in several types of cancers, including prostate cancer, lung cancer, glioma, etc [33–35]. In the three isoforms of the DNM family, DNM2 is ubiquitously expressed, whereas DNM1 and DNM3 are expressed in specific tissues. Here we investigated the expression and prognostic significance of DNM2 and identified it as a prognostic biomarker in PTC for the first time, providing more evidence of DNM2 implication in cancer and expanding the knowledge of PTC biomarkers.

DNM is well-accepted as a key modulator of endocytosis, especially CME. Ectopic CME function can affect tumor progression by regulating the recycling and trafficking of membrane receptors such as tyrosine-kinase receptor and G protein-coupled receptors [36]. For example, DNM2 downregulation delays EGFR endocytic trafficking and promotes EGFR signaling invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma and nonsmall-cell lung cancer cells [9,37]. Interestingly, there were other reports on the tumor-promoting function of DNM2 in addition to its function of regulating endocytosis. DNM2 can contribute to invadopodia formation via its GTPase function in bladder cancer [38], or interact with podocalyxin and regulate cytoskeletal dynamics to promote migration and metastasis in pancreatic cancer cells [30]. In our study, the molecular mechanism of how DNM2 correlated with the recurrence and prognosis was not further investigated, but it would be an interesting topic in the future.

Conclusions

Overall, our study demonstrated that DNM2 expression was significantly correlated with recurrence and prognosis of PTC by detecting DNM2 expression in 112 PTCs and evaluating its clinical significance. DNM2 was an independent prognostic biomarker and detecting expression of DNM2 may help to select high-risk patients for adjuvant therapy.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navas-Carrillo D, Rios A, Rodriguez JM, et al. Familial nonmedullary thyroid cancer: Screening, clinical, molecular and genetic findings. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1846(2):468–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitahara CM, Sosa JA. The changing incidence of thyroid cancer. Nature Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(11):646–53. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matrone A, Campopiano MC, Nervo A, et al. Differentiated thyroid cancer, from active surveillance to advanced therapy: Toward a personalized medicine. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:884. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreissl MC, Janssen MJR, Nagarajah J. Current treatment strategies in metastasized differentiated thyroid cancer. J Nuclear Med. 2019;60(1):9–15. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.190819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlumberger M, Challeton C, De Vathaire F, et al. Radioactive iodine treatment and external radiotherapy for lung and bone metastases from thyroid carcinoma. J Nuclear Med. 1996;37(4):598–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reis CR, Chen PH, Srinivasan S, et al. Crosstalk between Akt/GSK3beta signaling and dynamin-1 regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis. EMBO J. 2015;34(16):2132–46. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen PH, Bendris N, Hsiao YJ, et al. Crosstalk between CLCb/Dyn1-mediated adaptive clathrin-mediated endocytosis and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling increases metastasis. Dev Cell. 2017;40(3):278–88. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mettlen M, Chen PH, Srinivasan S, et al. Regulation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2018;87:871–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson SM, De Camilli P. Dynamin, a membrane-remodelling GTPase. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(2):75–88. doi: 10.1038/nrm3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antonny B, Burd C, De Camilli P, et al. Membrane fission by dynamin: What we know and what we need to know. EMBO J. 2016;35(21):2270–84. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan I, Gril B, Steeg PS. Metastasis suppressors NME1 and NME2 promote dynamin 2 oligomerization and regulate tumor cell endocytosis, motility, and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2019;79(18):4689–702. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu YF, Yang XQ, Lu XF, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 promotes progression and correlates to poor prognosis in cholangiocarcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu XJ, Liu WL, et al. Hepatoma-derived growth factor predicts unfavorable prognosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:2101–9. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S85660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun R, Liu Z, Qiu B, et al. Annexin10 promotes extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma metastasis by facilitating EMT via PLA2G4A/PGE2/STAT3 pathway. EBioMedicine. 2019;47:142–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Sun R, Zhang X, et al. Transcription factor 7 promotes the progression of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma by inducing the transcription of c-Myc and FOS-like antigen 1. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:181–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azim HA, Jr, Peccatori FA, Brohee S, et al. RANK-ligand (RANKL) expression in young breast cancer patients and during pregnancy. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:24. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0538-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeo W, Chan SL, Mo FK, et al. Phase I/II study of temsirolimus for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) – A correlative study to explore potential biomarkers for response. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:395. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1334-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu YF, Liu ZL, Pan C, et al. HMGB1 correlates with angiogenesis and poor prognosis of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma via elevating VEGFR2 of vessel endothelium. Oncogene. 2019;38(6):868–80. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernier MO, Leenhardt L, Hoang C, et al. Survival and therapeutic modalities in patients with bone metastases of differentiated thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(4):1568–73. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McWilliams RR, Giannini C, Hay ID, et al. Management of brain metastases from thyroid carcinoma: A study of 16 pathologically confirmed cases over 25 years. Cancer. 2003;98(2):356–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Untch BR, Dos Anjos V, Garcia-Rendueles MER, et al. Tipifarnib inhibits HRAS-driven dedifferentiated thyroid cancers. Cancer Res. 2018;78(16):4642–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu R, Bishop J, Zhu G, et al. Mortality risk stratification by combining BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations in papillary thyroid cancer: Genetic duet of BRAF and TERT promoter mutations in thyroid cancer mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(2):202–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vuong HG, Duong UN, Altibi AM, et al. A meta-analysis of prognostic roles of molecular markers in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Endocr Connect. 2017;6(3):R8–17. doi: 10.1530/EC-17-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vuong HG, Altibi AM, Duong UN, et al. Role of molecular markers to predict distant metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma: Promising value of TERT promoter mutations and insignificant role of BRAF mutations – a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2017;39(10) doi: 10.1177/1010428317713913. 1010428317713913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vuong HG, Altibi AMA, Duong UNP, Hassell L. Prognostic implication of BRAF and TERT promoter mutation combination in papillary thyroid carcinoma – a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol. 2017;87(5):411–17. doi: 10.1111/cen.13413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho AL, Grewal RK, Leboeuf R, et al. Selumetinib-enhanced radioiodine uptake in advanced thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(7):623–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, et al. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell. 2006;10(6):839–50. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong BS, Shea DJ, Mistriotis P, et al. A direct podocalyxin – dynamin-2 interaction regulates cytoskeletal dynamics to promote migration and metastasis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2019;79(11):2878–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chernikova SB, Nguyen RB, Truong JT, et al. Dynamin impacts homology-directed repair and breast cancer response to chemotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(12):5307–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI87191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joshi HP, Subramanian IV, Schnettler EK, et al. Dynamin 2 along with microRNA-199a reciprocally regulate hypoxia-inducible factors and ovarian cancer metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5331–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317242111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee YG, Nam Y, Shin KJ, et al. Androgen-induced expression of DRP1 regulates mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020;471:72–87. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu L, Xiao Z, Tu H, et al. The expression and prognostic significance of Drp1 in lung cancer: A bioinformatics analysis and immunohistochemistry. Medicine. 2019;98(48):e18228. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eugenio-Perez D, Briones-Herrera A, Martinez-Klimova E, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Divide et impera: Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in glioma malignancy. Yale J Biol Med. 2019;92(3):423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmid SL. Reciprocal regulation of signaling and endocytosis: Implications for the evolving cancer cell. J Cell Biol. 2017;216(9):2623–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201705017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong C, Zhang J, Zhang L, et al. Dynamin2 downregulation delays EGFR endocytic trafficking and promotes EGFR signaling and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5(2):702–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Nolan M, Yamada H, et al. Dynamin2 GTPase contributes to invadopodia formation in invasive bladder cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;480(3):409–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]