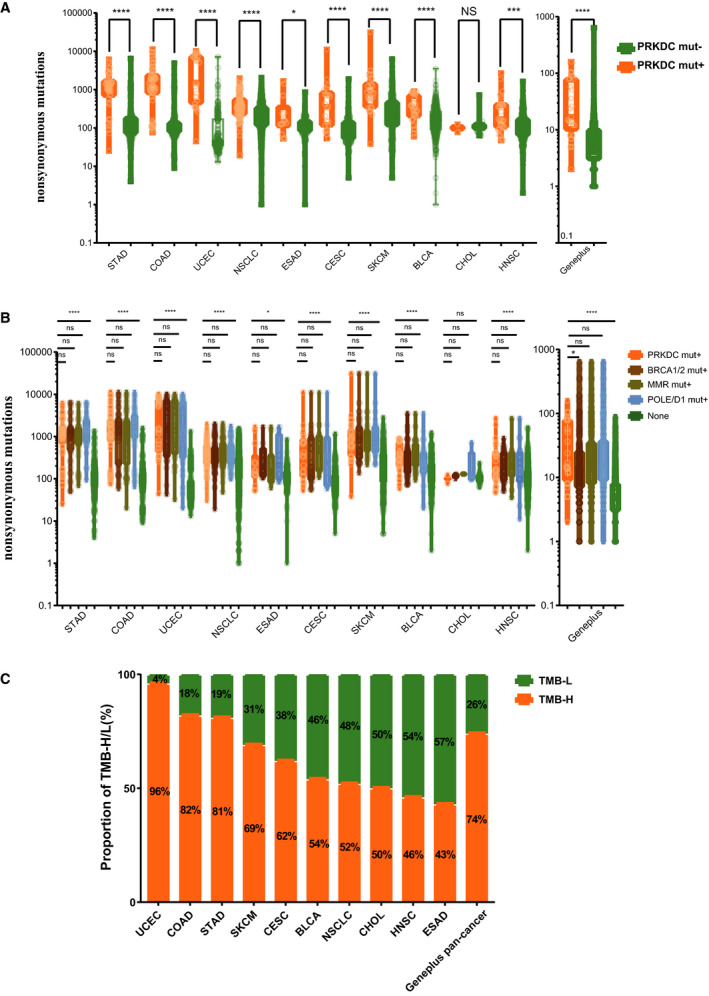

Fig. 2.

Relationships between TMB and PRKDC mutation status. (A) Comparison of TMB between PRKDC mutations and PRKDC wild‐type samples in TCGA top10 cancers and Geneplus pan‐cancer. TMB, defined as the sum of somatic nonsynonymous mutations. (B) Comparison of TMB between PRKDC mutations and other DDR‐gene (including BRCA1/BRCA2, PMS2/MSH2/MSH6/MLH1, POLE/POLD1) mutations in TCGA top10 cancers and Geneplus pan‐cancer. The none group was the referent group, defined as the absence of any of the aforementioned mutations. (C) The proportion of TMB‐high/low status in PRKDC mutation samples in TCGA top10 cancers and Geneplus pan‐cancer. TMB‐H, defined as the upper quartile of tumor all samples' TMB in each cancer type. Statistical significance was calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test. ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns P > 0.05. STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma (N = 436); COAD, colorectal adenocarcinoma (N = 528); UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (N = 248); NSCLC, non‐small‐cell lung cancer (N = 1031); ESAD, esophageal adenocarcinoma (N = 182); CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma (N = 281); SKCM, human skin cutaneous melanoma (N = 368); BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma (N = 412); CHOL, cholangiocarcinoma (N = 35); HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (N = 502); Geneplus, pan‐cancer samples in Geneplus‐Beijing Institute (N =。 3877). (N: the number of samples).