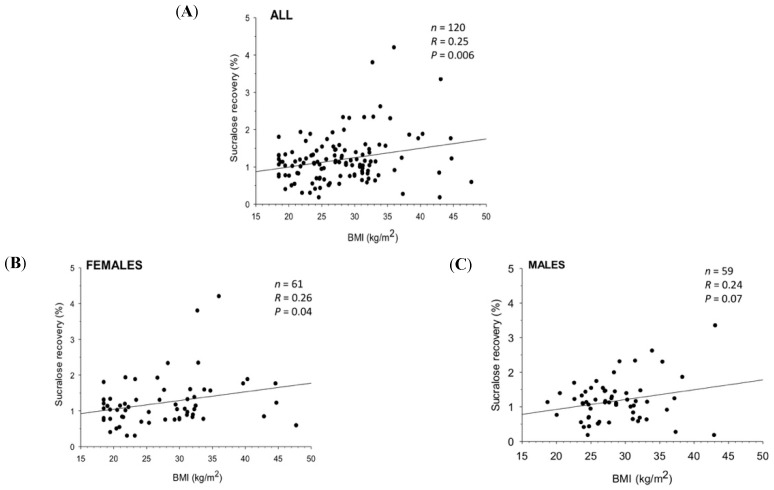

Figure 6.

Colonic permeability (leakage) in a group of 120 subjects (61 females and 59 males; mean age 45 ± SEM1.2 years, range 18–75). Graphs show the correlation between urinary sucralose recovery (marker of colonic permeability) and body mass index (BMI) in: (A) all subjects; (B) females; (C) males. The prevalence of abnormal colonic permeability was higher in both overweight and obese than in normal weight subjects, and sucralose recovery increased significantly with BMI overall, in females (p = 0.04), and tended to increase also in males (p = 0.07). To measure overall intestinal permeability, four saccharide probes are administered orally and simultaneously. Stomach permeability is assessed by administering 20 g of sucrose; small intestine permeability is assessed by administering lactulose (5 g) and mannitol (1 g); and colonic permeability is assessed with 1 g of sucralose. A urinary sample is collected in the morning of the test, after an overnight fast. Sugars are dissolved in 250 mL of tap water and orally administered. Urines are collected every hour during six hours in a sterile container. Urinary samples are measured by chromatography/mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS, AB Analitica, Padua, Italy). The fraction of the excreted sugars was calculated based on the quantity of sugar ingested by the patients and expressed as a percentage value, according to the manufacturer (AB analitica, Padua, Italy). Their presence in urine, in different amounts compared to the expected, indicated impaired permeability of the stomach, small intestine, or colon. Normal values for permeability test are expressed as a percentage) adapted from Di Palo et al. [167]).