Abstract

Context

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has impacted most elements of daily life, including the provision of support after a child's death and the experience of parental bereavement.

Objectives

This study aims to examine ways in which COVID-19 has affected the bereavement experiences of parents whose children died of cancer before the pandemic.

Methods

Parents who participated in a survey-based study examining the early grief experience were invited to complete a semistructured interview. During the interview, which focused on examining the current support for parents and other family members within the first several years after the child's death, participants were asked how COVID-19 has impacted their life and bereavement.

Results

Fifteen of 33 eligible parents completed the interview; 14 were white and non-Hispanic, five were males. Parents participated an average of 19 (range 12–34) months after their child's death. COVID-19 was addressed in 13 interviews. Eleven codes were used to describe interview segments; the most commonly used codes were change in support, no effect, familiarity with uncertainty/ability to cope, and change in contact with care/research team.

Conclusion

Parents identified multiple and variable ways—both positive, negative, and neutral—how COVID-19 has affected their bereavement. Many parents commented on feeling more isolated because of the inability to connect with family or attend in-person support groups, whereas others acknowledged their experience has made them uniquely positioned to cope with the uncertainty of the current situation. Clinicians must find innovative ways to connect with and support bereaved parents during this unique time.

Key Words: COVID-19, grief, bereavement, pediatric cancer, bereaved parents

Key Message

This article describes bereaved parents' perceptions of the mixed effects of coronavirus disease 2019 on their bereavement. The variable parental responses to coronavirus disease 2019 highlight the importance of continuing contact between the care team and family to assess coping and offer additional support as needed.

Honestly this epidemic is not even like a drop in the bucket of how hard things got for us …

—Bereaved parent

Introduction

The global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected most aspects of daily life, including the experience of death, grief, and bereavement.1 Forced changes in end-of-life care and rituals after death, physical distancing requirements, and changes to work and home life because of COVID-19 may affect individuals' bereavement. The current literature is focused on the adverse outcomes in adults bereaved because of the pandemic2 , 3 and ways to better support individuals who are grieving the death of loved ones killed by the virus.1 , 4 However, much less is known about the effect of the pandemic on the bereavement in individuals who experienced the death of a loved one before COVID-19.

Although parental grief decreases in intensity over time, the death of a child results in grief that is never ending.5 , 6 Social support after the child's death may help parents to work through their grief.7 However, both formal mental health and informal social support has been dramatically altered by the pandemic. We sought to examine the unexplored effect of COVID-19 on the bereavement of parents of children who died of cancer before the pandemic. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the various ways in which COVID-19 has altered parental bereavement.

Methods

Parents of children who died of cancer and had participated in a survey-based study examining the early grief experience of parents were invited to participate in a semistructured interview. In a previous study, parents of children who died of cancer 6–24 months prior completed a comprehensive survey. At the end of the survey, parents indicated if they would be willing to be contacted for future studies. The aim of the present study was to explore the early grief experience of parents of children who died of cancer, with emphasis on the support received, barriers to adequate support, and exploration of possible additional supportive interventions. Parents who indicated their openness to be recontacted were mailed a letter outlining the goals of the study. Parents could complete the interview alone or with a partner (if applicable). Phone interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim, excluding personal identifiers. All interviews were conducted by a female research assistant (G.H.) with a background in qualitative research. After the first four interviews were conducted, a specific question about the effect of COVID-19 was included. Parents were asked, Has COVID-19 or anything going on in the world right now impacted your experience at all and if so, how? This study was approved by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board.

Thematic analysis of interview transcripts was conducted using both inductive and deductive approaches.8 Initial coding was inductive and then combined with prefigured codes from the interview guide. Each transcript was independently coded by two team members (G.H. and J.M.S.), and the coders engaged in reflective discussion to resolve differences and refine codes. Thematic analysis was used to identify key impressions, contexts, and patterns across interviews. Ethnographic software (NVivo 12) was used for data management and to facilitate analysis.

Results

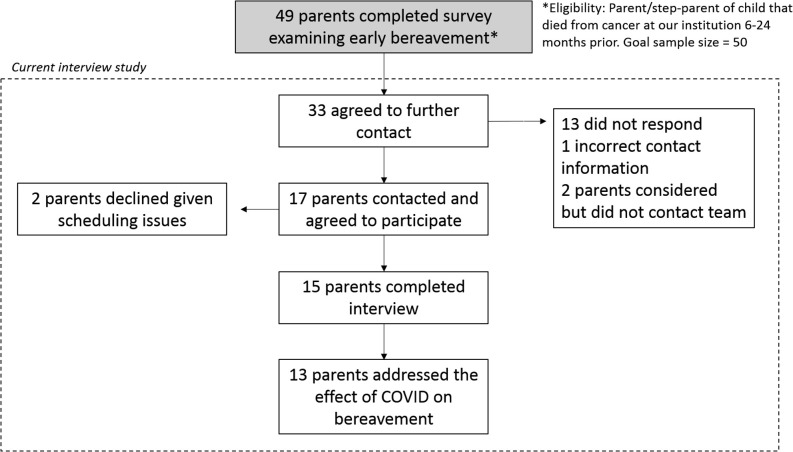

Thirty-three parents were sent a prenotice letter outlining the goals of the study, 17 parents agreed to participate, and 15 parents completed the interview (Fig. 1 ). All interviews were conducted alone with a research assistant in a single sitting. Interviews lasted an average of 32 (range 12–42) minutes. Eleven parents were asked directly about the impact of COVID-19, two parents brought up the topic on their own, and two parents did not mention COVID-19. Five fathers and 10 mothers participated, including three married couples. Parents participated an average of 19 (range 12–34) months from their child's death. One parent identified as Hispanic, all other parents were white and non-Hispanic. No further demographic information was collected.

Fig. 1.

Study eligibility and enrollment pathway. Shaded box indicates the number of parents who participated in the survey-based study examining the early psychosocial and health outcomes of parents of children who died of cancer. Parents who agreed to be contacted for further studies were approached to participate in semistructured interviews (dashed box). COVID = coronavirus disease.

Eleven codes were identified relating to the effect of the COVID pandemic on bereavement. Derived codes, definitions, and example quotations are presented in Table 1 . The most commonly used codes were change in support, no effect, familiarity with uncertainty/ability to cope, and change in contact with care/research team. Most parents spoke about how the pandemic has led to a change in the support they were receiving—often referencing an inability to meet with others face to face, with individual supportive figures or a support group. Parents also described changes in how they were in contact with their child's care team, with most noting that they had not heard from or were unable to visit with staff and clinicians in person. In contrast, one parent mentioned that the pandemic led to a new ability to participate in research meetings related to their child's diagnosis.

Table 1.

Bereaved Parents' (N = 13) Responses to the Question, Has COVID-19 or Anything Going on in the World Right Now Impacted Your Experience At All and If so, How?

| Code (Number of Parents Using Code) | Definition | Example Quotation(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change in support (8) | Difference (real or perceived) in the type or level of support felt prior; new/different ways to connect | I mean I guess it's – yeah, it definitely has, especially with so many anniversaries and his birthday and we couldn't be around friends or family. That was tough, since obviously we're trying to stay safe and everything. That was really hard.—Parent 581A | [Our therapist] keeps trying to fire us but we keep insisting, it's pretty funny. I think that's – I think she's the one who's been affected in COVID. I think people who work in that field are just overwhelmed.—Parent 550A |

| No effect (5) | No perceived change in bereavement or support | Well, actually, it really hasn't affected me, except for one way. But I'm home most of the time, anyways, and I don't really see anybody.—Parent 553A | |

| Familiarity with uncertainty/ability to cope (4) | Resiliency, adaptability, perspective, preparation for grief/uncertainty; pandemic making grief more universal | But I think the flip side or the good side of that … that I feel like there's also like a resiliency that we've got that I see other people not having quite as much because we kind of got used to just accepting things for what they were and then trying to move through it. And so I think that there's definitely a good side to it, too, and I think we have a way of coping that we've been able to extend into this time, so I think it's helped us as a family.—Parent 573A | It's not the fear of a pandemic. Because if any group of people are prepared to have their world turned upside down overnight and not really not know the future, those are familiar places.—Parent 505B |

| Change in contact with care/research team (4) | Shift in ways families communicate with their child's care team or research team; can be new/different ways | His care team – we've been visiting them before the COVID-19, and we usually just talk on [about] their lives and told them what was happening with us. So, they've been a very, very big support. But with this COVID-19, we have not been able to do that. But they have sent little notes and stuff.—Parent 582A | So we are in some ways trying to help get some more research in [my child's cancer diagnosis] … So we have checked with them in that sense just trying to understand what's going on and how are we making any sort of progress and with a cure … we've been like participating in … workshops through Zoom and other forms of communication that we'd be able to take part … And it has just helped us – keeps us informed, and I think we still want to be a part of that and that you somehow do care.—Parent 520B |

| Compounded isolation (3) | Physical distancing adding to already present sense of isolation or separation/feeling separate from others | For me, I kind of wanted to withdraw from the world and so COVID, the pandemic sort of played into that. I didn't really want to go out and have much social interaction … I think it's been a mixed bag. I think it's been helpful and what I needed to do at the same time might have slowed things down a little bit.—Parent 590B | |

| Thankfulness (2) | Parents expressing gratitude that child did not experience and/or they could experience EOL care before pandemic | It honestly makes me very – I feel – I'm so happy that [my child] didn't have to go through her sickness during this time. I keep saying … that she was able to receive care without masks and wasn't frightening … she was able to say good bye with the family. She was able to give everybody hugs … I'm glad she didn't have to suffer through this.—Parent 503A | |

| Trigger (2) | Pandemic and associated factors causing increased anxiety or triggering disturbing memories | For a long time I didn't know that was happening and I was having essentially panic episodes and could not link it to anything until I realized oh wait the smell of hand sanitizer is triggering this … There's just a whole array of physical symptoms that I wasn't necessarily connecting to the grieving process … And even our youngest who witnessed everything as a 2 and 3-year-old, all the sudden seeing everyone in masks has that same reaction.—Parent 505B | |

| Forced pause/time to grieve (2) | Time and space to do the work of grieving | Well, it's definitely mixed feelings. Like there's moments where I think it's good to be – if everybody could just stop and take – stop with their lives. And that's kind of like how I've been feeling for the past year and a half or two years, really, since my daughter's diagnosis that my life kind of stopped and I haven't really been out in the world so much. So I think right now is a time when everybody's experiencing some of that. And in ways it's good, like for me it has been good to just have the time to grieve more and really all those feelings kind of come back because it really resembles a lot of how I was feeling right after her passing or even just after her diagnosis … —Parent 520B | For me, I kind of wanted to withdraw from the world and so COVID, the pandemic sort of played into that. I didn't really want to go out and have much social interaction. And I think that's still here even though it's been just over a year now since my daughter died … I think it's been a mixed bag. I think it's been helpful and what I needed to do at the same time might have slowed things down a little bit.—Parent 590B |

| Loss of routine or personal time (2) | Chance in regular activities; less time to be alone | You don't realize your commute in the morning and getting out of your house and the movement and routine how, much of a help those are getting through everything.—Parent 505B | |

| Additional stress (1) | More strain or pressure | I said, you know – we tried to, met up, and we met up a couple of times and after COVID like we're dealing with all this extra stress and trying to do another Zoom thing, we were just like we just can't handle that. It was just hard to organize and motivate to do anything else. We're all pretty kind of stressed and dealing with a lot.—Parent 520B | |

| Constant reminders/no break from grief (1) | Surrounded by items, memories, feelings of grief | And when you take away your routine and now you're stuck in your house where there are the arts and craft pictures and the toys and the stuffed animals. And instead of having breaks from that you're in it all day – that can exacerbate a lot of the recovery stuff.—Parent 505B | |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; EOL = end of life.

Parents remarked that the pandemic increased their sense of isolation because of the physical separation from others and additional stress caused by the many life changes. Some parents found the change in routine and forced isolation beneficial, providing time and the presence of family members to do the work of grieving. In contrast, two parents noted the loss of routine and being homebound led to a constant reminder of their loss. Another parent expressed that although social isolation has provided time and space to reflect, it has also made it easier to withdraw from society.

Although parents acknowledged the negative impacts of COVID-19, these parents and others expressed feeling resilient and able to deal with the current uncertainty because of their experiences during their child's illness and death. Two parents expressed being thankful that their child did not have to experience the pandemic and that their child's end of life was not impacted. Two others spoke about how the elements of the pandemic (face masks and hand sanitizer) triggered negative emotions or traumatic stress in them or their family members.

Finally, three parents expressed that the pandemic has not influenced their bereavement, noting they have maintained their routine (work) or familial support. Two of these parents went on to explain one or more ways in which their bereavement has changed.

Discussion

Overall, parents expressed mixed effects of COVID-19 on their bereavement. The parents who participated in this study were early in the bereavement, with an average time since their child's death of 19 months. Given their proximity to their child's death, these parents may be more vulnerable to the more negative effects of the pandemic, particularly the loss of a support system, mental health or support group, or physical presence of a supportive figure or care team member. This is consistent with prior literature indicating that multiple losses or compounded isolation may worsen or exacerbate parental grief.6

Continued contact between bereaved families and members of the care team after the child's death is important in parental bereavement9 and has been identified as standard of care in pediatric oncology.10 Given the absence of structured activities, hospital visits, or memorials that allow families a chance to connect with their child's care team, parents may feel less supported now. Several parents shared ways in which clinicians and mental health providers had attempted to maintain supportive contact, including sending cards or notes or shifting support groups to virtual meetings. Clinicians must continue to adapt and innovate to develop new ways to provide ongoing support to parents of children who died and their family members throughout the pandemic and beyond.

Just as the experience of grief and bereavement is highly individual and likely differs from person to person,11 the effect of COVID-19 on each bereaved individual is variable. Some parents may be able to find strength or recognize their resiliency during this time, while other parents may be more affected by compounded isolation and require additional support from the care team, hospital, and local community. Clinicians should refrain from making assumptions about the impact of the pandemic on a person's or family's grief and instead proactively reach out to parents to let them know that their child and family are remembered and that additional supports are available.

There are several limitations to this study. Thirteen parents did not respond to invitations to participate in this study; the impact of COVID on these individuals may have been different. All participants were parents of children who were treated at a single tertiary care institute in a large metropolitan city. Very limited demographic information was collected, but available data indicate minimal ethnic/racial diversity. Concurrent with the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic consequences, calls and protests for racial justice and societal upheaval may disproportionally impact bereaved parents of color, which are not represented in the present study. Despite these limitations, we believe these findings are important as the first examination of the effect of the current pandemic on parental bereavement.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had mixed effects on parental bereavement. The social distancing requirements and other methods for slowing the spread have resulted in increased feelings of isolation and disruption of sometimes fragile support systems. Despite the many challenges imposed, many parents found some benefit in the current situation, including allowing more time to grieve and recognition of their coping skills and resiliency. Providers and hospitals should proactively contact bereaved parents to assess for the need of additional support and find innovative ways to connect and provide ongoing support for parents and families.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The authors thank the amazing parent participants in this study and who shared the stories of their children, families, and themselves. The authors have no disclosures to report. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mayland C.R., Harding A.J.E., Preston N., Payne S. Supporting adults bereaved through COVID-19: a rapid review of the impact of previous pandemics on grief and bereavement. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e33–e39. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kokou-Kpolou C.K., Fernandez-Alcantara M., Cenat J.M. Prolonged grief related to COVID-19 deaths: do we have to fear a steep rise in traumatic and disenfranchised griefs? Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S94–S95. doi: 10.1037/tra0000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goveas J.S., Shear M.K. Grief and the COVID-19 pandemic in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace C.L., Wladkowski S.P., Gibson A., White P. Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e70–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris S., Fletcher K., Goldstein R. The grief of parents after the death of a young child. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2019;26:321–338. doi: 10.1007/s10880-018-9590-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snaman J.M., Kaye E.C., Torres C., Gibson D., Baker J.N. Parental grief following the death of a child from cancer: the ongoing Odyssey. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:1594–1602. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreicbergs U.C., Lannen P., Onelov E., Wolfe J. Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: impact of professional and social support on long-term outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3307–3312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green J., Thorogood N. 4th ed. SAGE Publications; London: 2018. Qualitative methods for health research. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snaman J.M., Kaye E.C., Torres C., Gibson D.V., Baker J.N. Helping parents live with the hole in their heart: the role of health care providers and institutions in the bereaved parents' grief journeys. Cancer. 2016;122:2757–2765. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lichtenthal W.G., Sweeney C.R., Roberts K.E. Bereavement follow-up after the death of a child as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:S834–S869. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson A.L., Miller K.S., Barrera M. A qualitative study of advice from bereaved parents and siblings. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2011;7:153–172. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2011.593153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]