Abstract

Cinobufotalin injection, a traditional Chinese medicine preparation, successfully used for several years, might induce cardiotoxicity. The aim of the study was to evaluate the cardiotoxicity of cinobufotalin injection and the cardiotoxicity-preventive effect of sodium phenytoin in vivo. According to the 4 × 4 Latin square design, four Beagle dogs were allocated into four dose levels of 0, 0.3, 1, and 3 g/kg in treatment phases I–IV (cinobufotalin injection) and 3 g/kg in treatment phase V (cardiotoxicity antidote). The following parameters and endpoints were assessed: clinical observations, body weight, indicators of myocardial injury, and electrocardiogram (ECG) parameters. The cinobufotalin injection-related changes were observed in clinical observations (rapid breathing pattern), indicators of myocardial injury (increased cardiac troponin I, creatine kinase isoenzymes, and aspartate aminotransferase), and ECG graphics (arrhythmia) at 3 g/kg concentration in treatment phases I–IV. The cardiotoxicity of cinobufotalin injection was attenuated by sodium phenytoin in treatment phase V. The results confirmed the cardiotoxicity of cinobufotalin injection, and they might bring information about the appropriate monitoring time points and cardiotoxicity parameters in clinical practices and shed light on the treatment of cardiovascular adverse reactions.

Keywords: Beagle dog, bufalin, cardiotoxicity, cinobufotalin injection, cardiac troponin I

Introduction

Cinobufotalin injection (also called Huachansu injection), a kind of second-class and self-developed traditional Chinese medicine preparation, is a sterilized hot water extract of dried Bufo gargarizans skin prepared as an injection [1]. Several classes of compounds have been isolated from the skin of B. gargarizans, including peptides, steroids (bufadienolides and cholesterols), indole alkaloids, bufogargarizanines, and organic acid [2]. There are two primary biologically active chemical components of cinobufotalin injection, which are indole alkaloids (they are regarded as indole alkaloids due to the common characteristics of indole ring, such as bufothionine) and bufadienolides (a class of cardioactive C-24 steroids with a characteristic α-pyrone ring at C-17, such as bufalin, resibufogenin, and cinobufagin) [3–6]. Cinobufotalin injection inhibits tumor development; relieves cancerous pain; improves the quality of life of patients; controls the incidence of adverse effects in malignant pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, liver cancer, and lymphoma; and regulates immunity and anti-hepatitis B virus [7]. Consequently, it has been widely used in the clinic setup for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and other diseases since the 1970’s in China [8, 9].

A wide range of cases of adverse drug reactions/adverse drug events (ADR/ADE) induced by cinobufotalin injection have been reported as our knowledge with regard to the drug’s safety has advanced over the past 40 years. A recent study [10] has demonstrated that the incidence of ADR/ADE induced by cinobufotalin injection was the highest among 33 kinds of traditional Chinese medicine injections. The higher incidence of these ADR/ADE cases involved the following damages: skin and its accessory damage, medical site damage, nervous system damage, allergic reactions, and drug-related fever. The incidence of unexpected cardiac adverse effects was relatively lower (approximately 5.6%), but the consequences such as arrhythmia might be serious [11].

In the past, insufficient attention was paid to the safety of traditional Chinese medicines; therefore, there are only a small number of anesthetized and unconditioned animal trials on the cardiotoxicity of cinobufotalin injection [12, 13]. In conducting in vivo studies, it is preferable to use unanesthetized animals and animals conditioned to the laboratory environment [14, 15]. Hence, telemetry was used to detect the cardiotoxicity of the cinobufotalin injection in our good laboratory practice laboratory. Interestingly, a previous pilot study showed the use of cinobufotalin injection at doses of up to eight times higher than that typically used in China as safe [16]. This could be because appropriate monitoring parameters were not used to well evaluate the cardiotoxicity of cinobufotalin injection. Currently, symptomatic treatment is primarily being used when cardiotoxicity manifests in patients post-cinobufotalin injection; thus, finding the toxic substances and a specific drug to improve this current approach is essential. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the severity of cardiotoxicity caused by cinobufotalin injection, appropriate cardiotoxicity monitoring parameters, and seek corresponding treatment. We hypothesize that the data resulted from this study will guide future clinical applications of cinobufotalin injection.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The Beagle dog as the non-rodent species is accepted by the health authorities worldwide as an appropriate experimental animal with ample historical data.

Animal supplier: Beijing Marshall Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Species/Strain and Grade: Beagle dogs (conventional animals). Animals were barrier bred, free of infections before shipment, and treated in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986. The dogs were housed individually in four stainless steel cage at 18–26°C, 40–70% humidity, and on a 12 h dark/light cycle with free access to food and tap water ad libitum. The study was performed under Home Office License after institutional IACUC review (IACUC-2018-D-056). The dogs were implanted with telemetric transmitters for use in the study.

Number and Sex of Dogs Used in the Study: four female dogs.

Body Weight and Age of Animals at Grouping: approximately 7–11 kg and 3–4 years old, respectively.

Animals were maintained in pens and acclimatized under the care of institutional veterinary surgeons before the study per the study laboratory protocol. The dogs were fed a standard diet but fasted overnight before the study; water was provided ad libitum.

Reagents

All preparations were sterile; the containers were sterilized before using.

Cinobufotalin injection (0.5 g/ml) was obtained from Anhui Jinchan Biochemistry Company Ltd, Huaibei, China. The batch number: 171104–2. It was serial diluted to obtain 0.05 and 0.17 g/ml doses in 0.9% sodium chloride injection.

Sodium phenytoin was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China. The batch number: SLBB3874V. Sodium phenytoin injection was dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride injection to produce 40 mg/ml solution immediately before use.

Sodium chloride injection (0.9%) was obtained from Shanghai Changzheng Fumin Jinshan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China. The batch number: 1805230101.

Immunoassay kit of cardiac troponin I was obtained from BECKMAN COULTER, INC., CA, USA. The batch number: 831884.

Immunoassay kit of creatine kinase isoenzymes was obtained from BECKMAN COULTER, INC., CA, USA. The batch number: 724779.

Immunoassay kit of C-reactive protein was obtained from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan. The batch number: KL456 and KL457.

Experimental Design

Dose Levels

According to the package insert of cinobufotalin injection, the maximum clinical dose of intravenous injection is 0.167 g/kg, which is equivalent to 0.3 g/kg in the dog after conversion according to the body surface area. A dose-range finding study conducted by us showed that cinobufotalin injection-related changes in electrocardiogram (ECG) were noted at 2 g/kg (approximately six times the maximum clinical dose). Therefore, the dose levels selected for this study were 0.3, 1, and 3 g/kg, which are equal to approximately 1, 3, and 10 times the maximum clinical dose, respectively.

According to the results of pre-experiment study, the dose level of sodium phenytoin injection selected for this study was 10 mg/kg.

The following dose levels were selected, as shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Dose levels design

| Group no. | Group name | Dose level (g/kg) | Concentration (g/ml) | Dose volume (ml/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vehicle control | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 2 | Low dose | 0.3 | 0.05 | 6 |

| 3 | Middle dose | 1 | 0.17 | 6 |

| 4 | High dose | 3 | 0.5 | 6 |

4 × 4 Latin Square Design Plus Treatment V

Currently, Latin square design is a recommended design for cardiovascular safety pharmacological studies in conscious telemetred Beagle dogs [17], which can reduce the number of animals according to the 3R principle of animal welfare. The number of animals is the minimum number necessary to assess the potential toxicity of the test article. The 4 × 4 Latin square design was, as shown in Table 2–3:

Table 2.

4 × 4 Latin square design

| Animal no. | Treatment I | Treatment II | Treatment III | Treatment IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | V | L | H | M |

| 2 | L | M | V | H |

| 3 | M | H | L | V |

| 4 | H | V | M | L |

V: vehicle control group; L: low dose group; M: middle dose group; H: high dose group; at least 3 days washout period between two treatments.

Table 3.

An antidote in a clinically relevant dog model

| Animal no. | Treatment V |

|---|---|

| 1 | H + sodium phenytoin injection (10 mg/kg) |

| 2 | H + sodium phenytoin injection (10 mg/kg) |

| 3 | H + sodium phenytoin injection (10 mg/kg) |

| 4 | H + sodium phenytoin injection (10 mg/kg) |

H: high-dose group; at least 3 days washout period between two treatments.

Apparatus

Apparatus used are DSI/Ponemah Physiology Telemetry System (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN, USA); Hitachi-7180 Automatic Clinical Analyzer (HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan); and Access 2 immunoassay system (BECKMAN COULTER, INC., CA, USA).

Dosing

Cinobufotalin injection: Slow intravenous administration was selected. The frequency of dose was single dose during each treatment phase. A fixed dose volume of 6 ml/kg was used in the study. The volume was calculated to administer the required doses based on the animal’s weight on the day of experiment.

Sodium phenytoin injection: Slow intravenous administration was selected. The frequency of dose was single dose during treatment phase V. A fixed dose volume of 0.25 ml/kg was used in the study. The volume was calculated to administer the required doses based on the animal’s weight on the day of experiment. Antidotes were administered immediately after cinobufotalin injection.

Observation and Examination

Clinical observation

Clinical signs were observed at least twice on each dosing day (once pre-dose and once post-dose) and once daily during the washout period.

Body weight

Fasted body weight was recorded for all animals prior to dosing on each dosing day.

Indicators of myocardial injury

Cardiac troponin I (cTn-I) (treatment phases I–V)

Creatine kinase isoenzymes (CK-MB) (treatment phases I–IV)

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (treatment phases I–V)

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (treatment phases I–V)

C-reactive protein (CRP) (treatment phases I–V)

Blood sampling

Time Points: Pre-dose and post-dose (1.5, 3, and 24 h).

Blood Collection Site: Peripheral vein of the four limbs.

Blood Volume to be collected: Approximately 1.5 ml/time point/dog.

Preparation and Blood Processing: Blood samples were collected into the tubes containing heparin sodium and maintained on crushed ice or ice bag. The collected blood samples were centrifuged at approximately 1200 × g for 5 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the serum was transferred into a newly labeled tube. The samples were stored at 2–8°C for analysis.

Telemetric Measurements

Measurement method

Measurements were conducted in the animal home cage using RMC 1 biotelemetry receivers. The dogs could move freely in their cages during the study period.

Measured parameters

Heart rate (HR), unit: bpm

PR interval (PR-I), unit: ms

QRS duration (QRS), unit: ms

RR interval (RR-I), unit: ms

QT interval (QT-I), unit: ms

QTcR, unit: ms

QT-I is corrected for changes in the heart rate using the individual correction formula: heart rate corrected QT interval (QTcR) = QT-I + β (HRM-HR), where β is calculated as the slope of QT versus HR, and HRM is the mean heart rate, both of which are derived from the vehicle control group data at the time points stated below [18].

Data recording

Data were recorded continuously starting at least 1.25 h prior to dosing and until at least 24 h after dosing.

Data analysis

All parameters were reported at nominal time points of 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 24 h after dosing. Time 0 was the mean of four pre-dose values (−1.25, −1, −0.75, and −0.5 h). For ECG, the mean of 30 s consecutive data (15 s before and after each time point) at each time point was calculated. When the signal was unstable during the 30 s (the waveform could not be identified), the selection of the signal was performed according to the following principles. The time period selection for the signal analysis: when the data were unstable for time points <4 h, the mean value was calculated based on 30 s of consecutive data within 10 min (5 min before and after the nominated time point); when the data were unstable for time points ≥4 h, the mean value was calculated based on 30 s of consecutive data within 20 min, and 10 min before and after the nominated time point. Signal selection: the recent 30 s stable period on the left side of the unstable signal was first analyzed. When there was no stable signal on the left, the recent 30 s stable period on the right side of the unstable signal was analyzed. When there was no stable data at least for 30 s in the selected period for the signal analysis, the data of that time point were discarded without analysis or report.

Statistical Procedure

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistics were performed using SPSS 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were analyzed using the two-way ANOVA with post hoc test or Student’s t test. The results with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Clinical Observation

In treatment phases I–IV, no cinobufotalin injection-related abnormalities were noted in the clinical observation at 0, 0.3, and 1 g/kg doses. The cinobufotalin injection-related changes were observed immediately after administration at 3 g/kg dose, which included salivation, rapid breathing pattern, and astasia.

In treatment phase V, no cinobufotalin injection-related abnormalities were noted in the clinical observation in all animals.

Body Weight

No cinobufotalin injection-related changes in body weight were noted in treatment phases I–V as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Effects of cinobufotalin injection on body weights in treatment phases I–V (kg)

| Animal no. | Treatment phase | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | |

| 1 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 7.2 | 7.4 |

| 2 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 8.6 |

| 3 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.9 |

| 4 | 10.9 | 10.7 | 11 | 10.9 | 11.3 |

Indicators of Myocardial Injury

In treatment phases I–IV, a slight increase in cTn-I was noted at 1.5 and 3 h in the 1 g/kg cinobufotalin injection group and an apparent increase in cTn-I, CK-MB, and AST was noted at 1.5 and 3 h in the 3 g/kg cinobufotalin injection group compared with those in the vehicle group as shown in Table 5 and Fig. 1. Moreover, cinobufotalin injection-related increase in AST, cTn-I, and CK-MB was observed at 1.5 and 3 h post-dose in the 3 g/kg cinobufotalin injection group compared with that pre-dose as shown in Fig. 2. No statistically significant difference was noted due to the higher standard deviation value.

Table 5.

Effects of cinobufotalin injection on indicators of myocardial injury in treatment phases I–V

| Indicator | Time | 0 g/kg | 0.3 g/kg | 1 g/kg | 3 g/kg | 3 g/kg + sodium phenytoin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST(U/L) | Pre-dose | 31.25 ± 4.86 | 28.25 ± 5.06 | 35.25 ± 12.97 | 31.00 ± 10.74 | 45.25 ± 14.66 |

| CRP(U/L) | 0.12 ± 0.07 | 0.11 ± 0.07 | 0.11 ± 0.08 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.20 | |

| LDH(U/L) | 184.50 ± 108.76 | 145.25 ± 84.92 | 193.00 ± 198.94 | 166.00 ± 137.78 | 192.25 ± 76.78 | |

| cTn-I(ng/mL) | 0.0033 ± 0.0023 | 0.0052 ± 0.0064 | 0.0362 ± 0.0335 | 0.0036 ± 0.0043 | 0.0049 ± 0.0022 | |

| CK-MB(ng/mL) | 1.4155 ± 0.3080 | 1.5060 ± 0.2639 | 1.6519 ± 0.3527 | 1.3647 ± 0.2780 | ||

| AST(U/L) | Post-dose 1.5 h | 28.50 ± 5.80 | 28.50 ± 4.65 | 34.75 ± 12.12 | 179.00 ± 172.00 | 100.00 ± 47.69 |

| CRP(U/L) | 0.10 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.14 ± 0.07 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.15 | |

| LDH(U/L) | 90.25 ± 40.04 | 109.00 ± 78.64 | 104.75 ± 32.52 | 176.50 ± 120.46 | 146.00 ± 25.02 | |

| cTn-I(ng/mL) | 0.0043 ± 0.0037 | 0.0058 ± 0.0069 | 0.0389 ± 0.0242 | 2.1579 ± 1.4899 | 0.1112 ± 0.1433* | |

| CK-MB(ng/mL) | 2.1450 ± 1.7718 | 2.2700 ± 1.2970 | 1.7908 ± 0.8892 | 15.7848 ± 7.7871 | ||

| AST(U/L) | Post-dose 3 h | 27.75 ± 5.62 | 26.50 ± 3.79 | 32.50 ± 9.15 | 159.25 ± 142.42 | 68.75 ± 30.35 |

| CRP(U/L) | 0.10 ± 0.07 | 0.12 ± 0.08 | 0.19 ± 0.14 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.15 ± 0.19 | |

| LDH(U/L) | 67.50 ± 23.73 | 64.25 ± 34.88 | 69.25 ± 14.82 | 121.00 ± 38.88 | 110.25 ± 21.30 | |

| cTn-I(ng/mL) | 0.0041 ± 0.0028 | 0.0081 ± 0.0104 | 0.0371 ± 0.0236 | 7.2056 ± 5.4921 | 0.3207 ± 0.4611* | |

| CK-MB(ng/mL) | 1.4139 ± 0.1945 | 1.3154 ± 0.1383 | 1.6888 ± 0.4881 | 18.6312 ± 9.6037 | ||

| AST(U/L) | Post-dose 24 h | 27.50 ± 5.45 | 27.25 ± 3.95 | 33.50 ± 10.34 | 33.75 ± 16.30 | 88.25 ± 44.69 |

| CRP(U/L) | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.26 ± 0.33 | 0.17 ± 0.12 | 0.22 ± 0.14 | |

| LDH(U/L) | 88.75 ± 20.79 | 86.00 ± 33.36 | 101.75 ± 49.41 | 95.25 ± 59.42 | 102.00 ± 20.54 | |

| cTn-I(ng/mL) | 0.0036 ± 0.0025 | 0.0047 ± 0.0062 | 0.0206 ± 0.0119 | 1.5367 ± 1.1296 | 0.0658 ± 0.0729* | |

| CK-MB(ng/mL) | 1.2210 ± 0.2975 | 1.5899 ± 0.8940 | 1.5830 ± 0.3265 | 4.3854 ± 1.8373 |

Note: Comparison between 0.3–3 g/kg groups and the vehicle control group or pre-dose (the two-way ANOVA with post hoc test), P > 0.05; n = 4.

Comparison between 3 g/kg + sodium phenytoin groups and the 3 g/kg group (Student’s t test), *: P < 0.05; n = 4.

Figure 1.

(A–C) The change of AST, CK-MB and cTn-I in treatment phases I–IV. Data were shown as mean ± SD, n = 4, P > 0.05, versus control (two-way ANOVA).

Figure 2.

(A–D) Indicators of myocardial injury (AST, cTn-I and CK-MB) were observed at pre-dose, 1.5, 3 and 24 h post-dose in all cinobufotalin injection-treated groups. Data were shown as mean ± SD, n = 4, P > 0.05, versus the pre-dose (two-way ANOVA).

In treatment phase V, a significantly decrease in cTn-I was noted in 3 g/kg cinobufotalin injection + sodium phenytoin injection group compared with 3 g/kg cinobufotalin injection group as shown in Table 5. The tendency of time effect curve was similar to treatment phases I–IV as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

The time-effect curve of cTn-I in treatment phase V (the time-effect curve of cTn-I at 3 g/kg was as a reference). Data were shown as mean ± SD, n = 4, *: P < 0.05, versus 3 g/kg group (Student’s t test).

Telemetric Measurements

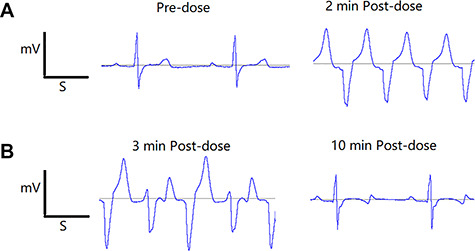

In treatment phases I–IV, arrhythmia, which causes the waveform to be unidentifiable, was noted in the 3 g/kg cinobufotalin injection group between immediately and 10 min post-dose as shown in Fig. 4. Furthermore, no cinobufotalin injection-related changes in ECG parameters (PR, RR, QRS, QT-I, QTcR, and HR) were observed at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 24 h post-dose in all cinobufotalin injection groups compared with those in the vehicle control group or pre-dose as shown in Table 6.

Figure 4.

(A and B) In treatment phases I–IV, arrhythmia, which causing the waveform was unable to be identified, was noted at 3 g/kg between immediately and 10 min post-dose.

Table 6.

Effects of cinobufotalin injection on ECG in treatment phases I–V

| Indicator | Time | 0 g/kg | 0.3 g/kg | 1 g/kg | 3 g/kg | 3 g/kg + sodium phenytoin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR-I | Pre-dose | 608.64 ± 106.08 | 684.47 ± 60.60 | 594.52 ± 126.39 | 589.27 ± 206.17 | 680.89 ± 128.86 |

| HR | 107.10 ± 24.36 | 92.82 ± 5.46 | 108.67 ± 30.33 | 118.58 ± 55.90 | 93.68 ± 21.05 | |

| QRS | 35.04 ± 2.80 | 34.45 ± 4.17 | 36.66 ± 2.09 | 35.16 ± 3.98 | 35.53 ± 2.58 | |

| PR-I | 93.46 ± 10.84 | 97.66 ± 13.82 | 93.70 ± 12.09 | 90.78 ± 12.00 | 99.74 ± 10.93 | |

| QT-I | 221.40 ± 27.24 | 225.88 ± 25.79 | 237.01 ± 72.96 | 217.08 ± 47.68 | 249.85 ± 61.37 | |

| QTcR | 219.42 ± 24.14 | 219.75 ± 25.16 | 235.59 ± 66.53 | 219.22 ± 33.79 | 243.05 ± 55.82 | |

| RR-I | Post-dose 0.25 h | 540.35 ± 154.21 | 540.09 ± 141.78 | 475.71 ± 133.23 | 481.23 ± 78.75 | 487.84 ± 73.34 |

| HR | 120.63 ± 45.20 | 118.63 ± 38.78 | 135.89 ± 47.11 | 127.38 ± 22.13 | 124.96 ± 17.48 | |

| QRS | 35.17 ± 3.55 | 34.99 ± 3.89 | 34.24 ± 3.64 | 37.73 ± 5.30 | 35.35 ± 2.38 | |

| PR-I | 91.15 ± 15.76 | 93.58 ± 17.37 | 88.82 ± 13.11 | 84.93 ± 8.98 | 91.97 ± 8.45 | |

| QT-I | 219.28 ± 48.72 | 230.12 ± 57.95 | 205.37 ± 57.76 | 240.62 ± 62.65 | 197.20 ± 17.95 | |

| QTcR | 222.15 ± 35.84 | 232.27 ± 51.42 | 213.73 ± 47.57 | 245.92 ± 59.53 | 201.63 ± 14.81 | |

| RR-I | Post-dose 0.5 h | 533.04 ± 108.53 | 486.54 ± 115.38 | 425.46 ± 113.77 | 559.28 ± 85.22 | 516.13 ± 39.54 |

| HR | 116.18 ± 23.67 | 128.67 ± 30.28 | 150.26 ± 47.01 | 109.33 ± 17.97 | 116.75 ± 8.75 | |

| QRS | 38.90 ± 2.11 | 34.62 ± 4.58 | 33.63 ± 2.69 | 35.32 ± 2.87 | 34.45 ± 3.25 | |

| PR-I | 103.53 ± 9.53 | 82.51 ± 6.38 | 89.45 ± 13.24 | 97.13 ± 14.04 | 104.60 ± 7.48 | |

| QT-I | 208.96 ± 25.54 | 202.13 ± 17.48 | 187.93 ± 21.20 | 262.92 ± 70.04 | 217.37 ± 46.48 | |

| QTcR | 210.24 ± 18.79 | 207.89 ± 16.53 | 201.46 ± 5.99 | 261.74 ± 70.53 | 218.85 ± 43.74 | |

| RR-I | Post-dose 1 h | 704.45 ± 132.01 | 666.62 ± 76.82 | 649.65 ± 172.35 | 653.37 ± 140.17 | 557.89 ± 137.77 |

| HR | 87.56 ± 17.16 | 90.97 ± 11.20 | 99.44 ± 35.63 | 94.56 ± 17.01 | 113.11 ± 30.65 | |

| QRS | 35.69 ± 4.91 | 35.02 ± 2.95 | 36.53 ± 4.26 | 36.69 ± 2.56 | 34.27 ± 3.33 | |

| PR-I | 92.58 ± 6.01 | 99.27 ± 17.33 | 91.70 ± 14.39 | 97.46 ± 9.93 | 103.38 ± 6.92 | |

| QT-I | 231.67 ± 19.47 | 250.84 ± 72.96 | 241.03 ± 74.92 | 245.30 ± 36.25 | 209.04 ± 17.44 | |

| QTcR | 222.66 ± 24.04 | 243.05 ± 70.97 | 236.29 ± 68.92 | 238.81 ± 36.93 | 209.21 ± 7.35 | |

| RR-I | Post-dose 2 h | 599.84 ± 184.60 | 693.20 ± 223.73 | 639.95 ± 95.32 | 561.42 ± 68.41 | 588.46 ± 101.91 |

| HR | 110.66 ± 46.50 | 96.37 ± 41.17 | 95.23 ± 13.27 | 108.07 ± 13.11 | 104.13 ± 16.83 | |

| QRS | 34.38 ± 3.15 | 36.22 ± 4.85 | 36.48 ± 3.19 | 36.87 ± 4.39 | 34.55 ± 3.15 | |

| PR-I | 88.01 ± 14.47 | 103.31 ± 16.88 | 94.47 ± 12.82 | 86.35 ± 12.04 | 101.77 ± 9.36 | |

| QT-I | 213.12 ± 40.64 | 231.81 ± 40.86 | 231.82 ± 60.26 | 235.61 ± 30.77 | 229.18 ± 33.84 | |

| QTcR | 212.41 ± 30.44 | 225.97 ± 31.36 | 225.57 ± 55.89 | 233.97 ± 28.08 | 226.13 ± 28.91 | |

| RR-I | Post-dose 4 h | 754.59 ± 142.22 | 699.22 ± 218.89 | 766.60 ± 64.45 | 512.09 ± 29.39 | 656.93 ± 236.65 |

| HR | 81.49 ± 14.02 | 95.71 ± 42.38 | 78.72 ± 7.10 | 117.46 ± 6.72 | 101.18 ± 36.76 | |

| QRS | 38.11 ± 2.94 | 37.15 ± 1.75 | 38.18 ± 1.79 | 36.23 ± 3.22 | 36.98 ± 4.73 | |

| PR-I | 97.67 ± 2.47 | 101.99 ± 21.27 | 94.48 ± 18.90 | 89.67 ± 6.32 | 99.47 ± 14.65 | |

| QT-I | 240.56 ± 35.21 | 251.73 ± 77.77 | 254.20 ± 61.03 | 236.63 ± 48.92 | 226.26 ± 27.79 | |

| QTcR | 229.37 ± 37.43 | 245.65 ± 67.99 | 242.01 ± 63.56 | 238.36 ± 47.04 | 222.15 ± 21.02 | |

| RR-I | Post-dose 24 h | 572.74 ± 174.00 | 632.19 ± 271.19 | 573.05 ± 213.45 | 658.95 ± 233.33 | 832.10 ± 249.85 |

| HR | 115.50 ± 47.61 | 107.94 ± 42.54 | 123.48 ± 68.18 | 104.18 ± 50.44 | 77.62 ± 24.75 | |

| QRS | 35.26 ± 3.96 | 34.83 ± 3.78 | 36.89 ± 4.16 | 35.12 ± 2.74 | 35.67 ± 3.15 | |

| PR-I | 89.54 ± 6.26 | 97.73 ± 11.24 | 88.80 ± 18.78 | 90.34 ± 11.65 | 99.91 ± 6.28 | |

| QT-I | 210.92 ± 20.30 | 231.21 ± 64.17 | 240.86 ± 91.34 | 231.08 ± 41.08 | 264.23 ± 80.00 | |

| QTcR | 211.96 ± 9.36 | 229.53 ± 52.19 | 244.76 ± 77.72 | 228.05 ± 29.23 | 251.65 ± 73.98 |

Note: Comparison between 0.3–3 g/kg groups and the vehicle control group or pre-dose (the two-way ANOVA with post hoc test), P > 0.05, n = 4.

Comparison between 3 g/kg + sodium phenytoin groups and the 3 g/kg group (Student’s t test), P > 0.05, n = 4.

In treatment phase V, the Beagle dog administered 3 g/kg cinobufotalin injection + sodium phenytoin presented abnormal graphics, which caused the waveform to be unidentifiable, between immediately and 7 min post-dose as shown in Fig. 5. Furthermore, no cinobufotalin injection-related changes in ECG parameters (PR, RR, QRS, QT-I, QTcR, and HR) were observed at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 24 h post-dose in the treated groups compared with those in 3 g/kg cinobufotalin injection group as shown in Table 6.

Figure 5.

In treatment phase V, arrhythmia, which causing the waveform was unable to be identified, was noted at 3 g/kg + sodium phenytoin between immediately and 7 min post-dose.

Discussion

In order to optimize cardiovascular stability and reduce both variability and number of animals required, the study was carried out in unrestrained four Beagle dogs with telemetry system because well controlled human studies are not possible. This does not match the real-life situation in which patients would not be implanted with telemetric transmitters. However, unrestrained Beagle dog cardiorespiratory physiology is similar to humans, and data from animals conditioned to the laboratory environment are preferable to data from unconditioned animals [14, 15].

Cardiac glycoside is one of the main pharmacological and toxicological components of cinobufotalin injection; we selected the corresponding antidote according to their pharmacological mechanism. However, cinobufotalin injection contains multiple ingredients; further studies on the characterization and reconstitution of the detailed ingredients with robust chemical fingerprinting are required to determine whether the type of antidote we choose is appropriate.

The changes noted in the clinical observation and ECG elucidate that cinobufotalin injection can substantially affect the electrophysiological state of the heart at lower concentrations, and the toxic effect of cinobufotalin injection is very short. Clinical adverse reactions report [19] showed that most of the adverse reactions of cinobufotalin injection occurred within 30 min after administration, and cardiovascular adverse reactions include arrhythmia and rapid breathing pattern. The present results were similar to that of the clinical adverse reactions report. Arrhythmia, which lasted for a short period, immediately occurred after the drug administration suggesting that an ECG should be monitored in all patients after drug administration. In addition, dog telemetry studies have good repetition. Furthermore, objective data are close to those under the normal condition [20]. The cardiotoxicity of cinobufotalin injection has been detected with telemetry in dogs, which pointed out that telemetry technology can be used to evaluate the cardiotoxicity of traditional Chinese medicine.

Except for changing the electrophysiological state of the heart, it is necessary to know whether cardiac myocytes could be damaged in vivo. Therefore, five indicators of myocardial injury (CRP, LDH, cTn-I, CK-MB, and AST in serum) were chosen to predict myocardial cell damage. The results suggested the following: (i) the cardiomyocyte injury could be detected from peripheral blood in 1.5 h; (ii) the degree of injury reached its peak in 3 h; (iii) the change in AST was reconvertible and the change in cTn-I and CK-MB showed recovery tendency in 24 h; (iv) in treatment phases I–IV, the change in cTn-I showed a dose-dependent increase compared with AST and CK-MB; and (v) in treatment phase V, only a significant change in individual cTn-I in the four dogs was noted, which highlighted that cTn-I is the most sensitive indicator compared with other indicators. This result was also consistent with that of previous studies [21, 22]. In addition, cTn-I could improve cardiovascular risk prediction in clinical application [23, 24], which suggested that it may be used as a biomarker for detecting the cardiotoxicity of cinobufotalin injection.

These results revealed that the safety range of cinobufotalin injection was narrow. Furthermore, the drug might exert unexpected effects on the treated and/or diseased heart that is hidden in the healthy myocardial cells [25]. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to find an appropriate treatment. Like other cardiotonic steroids such as ouabain and digoxin, bufadienolides have been reported as Na+, K+-ATPase inhibitors. Both direct and/or indirect cardiac effects of bufadienolides are known to occur [4, 26]. Furthermore, various myocardial cytotoxicity tests in vitro conducted in our laboratory showed that bufalin can induce significant cardiotoxicity at micromole concentrations (bufalin increased the late sodium current with an EC50 of 2.48 μM and increased NCX current with an EC50 of 66.06 μM in hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes). There were two primary biologically active chemical components of cinobufotalin injection, which were indole alkaloids and bufadienolides. Both direct and indirect mediated cardiac effects of bufadienolides (such as bufalin, resibufogenin, and cinobufagin) are known to occur. Indirect mediated cardiac effects of indole alkaloids (such as bufothionine) are known to occur [19]. We deduce that bufadienolides are more powerful than indole alkaloids to induce cardiotoxicity. Here, we chose sodium phenytoin as a potential antidote, which can compete with cardiac glycosides for cardiac-binding sites and inhibit intracellular influx of sodium and calcium ions [27, 28], to clarify the toxic substance of cardiotoxicity induced by cinobufotalin injection. The results of treatment phase V showed that the cardiotoxicity was markedly reduced, which confirmed our prediction, and suggested that cardiac glycoside antagonists could be used for the treatment of cardiovascular adverse reactions caused by cinobufotalin injection.

Conclusions

The current study confirmed the cardiotoxicity of cinobufotalin injection using telemetry, to the best of our knowledge, for the first time. Also, the current study shed more light on the appropriate monitoring time points and parameters for detecting the cardiotoxicity, and finally, the cardiotoxicity observed was attenuated by sodium phenytoin, which supports the treatment implications of clinical cardiovascular adverse reactions.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Chengju Zhang for their technical and critical comments on the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

M.L. and X.W. designed the research. M.L., Y.Q., T.C., B.R. and L.H. performed the experiments. N.T., X.P. and S.S. prepared all figures. M.L., X.W. and Y.Q. wrote the main manuscript text. H.L. revised the manuscript text and figures and provided scientific suggestions. All authors analyzed data and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Foundation of Science and Technology (2018ZX09201017-008).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ADR/ADE, adverse drug reaction/adverse drug event; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CK-MB, creatine kinase isoenzyme; cTn-I, cardiac troponin-I;; CRP, C-reactive protein; EC50, concentration for 50% of maximal effect; ECG, electrocardiogram; GLP, good laboratory practice; HR, heart rate; IACUC, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; NCX, Na+-Ca2+ exchange; PR-I, PR interval; QTcR, heart rate corrected QT interval; QT-I, QT interval.

References

- 1. Wang TT, Xu GX. Advancement on study of pharmacological action and clinical application of cinobufotalin. Int J Ophthalmol 2009;9:1330–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang D L, Qi FH, Tang W. et al. Chemical constituents and bioactivities of the skin of Bufo gargarizans Cantor. Chem Biodivers 2011;8:559–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Su YH, Nu X. Evaluation of pharmacodynamic effect of pharmaceutical agents of Chan Su. J Beijing Univ of TCM 2001;24:51–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Qi F, Li A, Inagaki Y. et al. Antitumor activity of extracts and compounds from the skin of the toad Bufo gargarizans Cantor. Int Immunopharmacol 2011;11:342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhan X, Wu H, Wu H. et al. Metabolites from Bufo gargarizans (cantor, 1842): a review of traditional uses, pharmacological activity, toxicity and quality control. J Ethnopharmacol 2020;246:112178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wei WL, Hou JJ, Wang XYY. et al. Venenum bufonis: an overview of its traditional use, natural product chemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and toxicology. J Ethnopharmacol 2019;237:215–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu XY, Tian F, Zhu XJ. et al. Progress of cinobufotalin antitumor research. Chin Med J Res Prac 2018;32:82–6 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luo C, Zhao HY, Bian BL. et al. Cinobufotalin injection for chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review. Chin J Exp Tradit Med Formulae 2014;20:212–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jiang QW, Chen T. Research progress on anti-tumor mechanisms and adverse reactions of cinobufagin. Lishizhen Medicine and Materia Medica Research 2015;26:2737–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng J, Han YX, Zhang SY. et al. Analysis of 369 cases of ADR/ADE induced by traditional Chinese medicine injections. J Pharmacoepidemiol 2018;27:113–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu B. Adverse drug reactions induced by cinobufotalin injection:literature analysis of 252 cases. J China Pharmacy 2011;22:1096–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu JD, Chen HJ, Guo MJ. Preliminary research of the effect of cinobufotalin injection on cardiac hemodynamics in anesthetized dogs. Acta Academiae Medicinae Xuzhou 1997;17:284–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feng GS, Luo P, Chen JW. et al. Effect of cinobufotalin freeze-dry powder on heart rate and electrocardiograph of anesthesia rats. Herald of Medicine 2015;34:448–51. [Google Scholar]

- 14. ICH ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: safety pharmacology studies for human pharmaceuticals S7A. ICH, 2000. http://www.ich.org/LOB/media./MEDIA504.pdf (8 November 2000, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 15. ICH ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: the non-clinical evaluation of the potential for delayed ventricular repolarization (QT interval prolongation) by human pharmaceuticals S7B. ICH, 2005. http://www.ich.org/LOB/media/MEDIA2192.pdf (12 May 2005, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meng Z, Yang P, Shen Y. et al. Pilot study of huachansu in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, nonsmall-cell lung cancer, or pancreatic cancer. Cancer 2009;115: 5309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Batey AJ, Doe CPA. A method for QT correction based on beat-to-beat analysis of the QT/RR interval relationship in conscious telemetred beagle dogs[J]. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2002;48:11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ollerstam Persson AH, Visser SA, Fredriksson JM. et al. A novel approach to data processing of the QT interval response in the conscious telemetered beagle dog. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2007;55:35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheng M. Analysis on 272 cases of adverse reactions/incidents induced by cinobufotalin injection. China Pharmaceuticals 2013;22:71–2. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malik M, Färbom P, Batchvarov V. et al. Relation between QT and RR intervals is highly individual among healthy subjects: implications for heart rate correction of the QT interval. Heart 2002;87:220–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. FDA Review of qualification data for cardiac troponins. EB/OL. www.fda.gov/.../drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/drugdevelopmenttoolsqualificationprogram/ucm382535.pdf (24 January 2011, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Porter A, Rozanski E, Price LL. et al. Evaluation of cardiac troponin I in dogs presenting to the emergency room using a point-of-care assay. The Canadian veterinary journal. Can Vet J 2016;57:641–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tucker JF, Collins RA, Anderson AJ. et al. Early diagnostic efficiency of cardiac troponin I and troponin T for acute myocardial infarction. Acad Emerg Med 1997;4:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lan NSR, Bell DA, McCaul KA. et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I improves cardiovascular risk prediction in older men: HIMS (the health in men study). J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e011818. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferdinandy P, Baczko I, Bencsik P. et al. Definition of hidden drug cardiotoxicity: paradigm change in cardiac safety testing and its clinical implications. Eur Heart J 2018;0:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Demiryürek AT, Demiryürek S.. Cardiotoxicity of digitalis glycosides: roles of autonomic pathways, autacoids and ion channels. J Autonomic & Autacoid Pharmacology 2015;25:35–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lu WJ, Zhou J, Ma HY. et al. Effect of anti-arrhythmia drugs on mouse arrhythmia induced by Bufonis Venenum[J]. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2011;46:1187–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Suwalsky M, Mennickent S, Norris B. et al. The antiepileptic drug phenytoin affects sodium transport in toad epithelium. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2006;142:253–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]