Abstract

Organophosphates are a large class of chemicals with anticholinesterase action insecticides. Dimethoate belongs to the class of organophosphates and it is used for agriculture purpose. Its main toxicological role in animals and humans is the inhibition of the activity of acetylcholinesterase. Although it is not considered genotoxic, carcinogenic and teratogen, there is evidence of increased pup mortality in developmental neurotoxicity studies. Since there is scant published literature about developmental toxicity, we investigated the adverse effects of dimethoate on fertilization and embryonic development in sea urchin (Paracentrotus lividus), a model organism widely used to assess the toxicity of contaminants on environmental matrices; so pesticide residues can be released into the environment, and could affect the health of organisms, including humans. Different solution of dimethoate (4 × 10−3, 4 × 10−4, 4 × 10−5, 4 × 10−6 and 4 × 10−7 g/10 ml) have been tested on spermatozoa of P. lividus to evaluate the fertilizing ability of them when we added egg cells untreated. We demonstrated that dimethoate does not interfere with fertilizing ability of spermatozoa but egg cells fertilized by treated spermatozoa showed alterations in the segmentation planes as asymmetric and/or asynchronous cell divisions.

Keywords: organophosphates, mutagenesis, sea urchin, spermatozoa, eggs, zygote

Introduction

The use of pesticides has certainly helped to protect crops by encouraging greater agricultural production to cope with the increase in the world population. Pesticides are designed to control pests with minimal effects on people and the environment [1]; despite these advantages, they represent a potential danger to human health and the environment [2–4]. For this reason, the European Union has regulated its use, establishing the maximum residue levels (MRLs) of pesticides allowed by law inside or on the surface of food or feed, as well as the minimum exposure of the consumer. The levels are obtained after a complete evaluation of the properties of the active substance and the intended use of the pesticide [5]. Although often the aquatic environment is not the primary site of application of pesticides, the aquatic organisms are affected by pesticides leaching into the waters through agricultural run-off [6]. The presence of pesticides in the environment represents a risk to both ecosystems and humans [7]. Humans can assimilate hazardous chemicals through food and water, but also through the respiratory tract and the skin [4]. Oral exposure depends on the presence of residues of the substance in food and drinking water and the quantities of food and water consumed. Pesticides, from a regulatory point of view, include plant protection products [8] used for plant protection and conservation of plant products, and biocides [9] used in various fields of activity (disinfectants, preservatives, pesticides for non-agricultural use, etc.). Often the two types of products use the same active ingredients [4]. Plant protection products are classified according to the different classes of chemical compounds that compose them. The three most widespread groups of chemical compounds are: organophosphates, carbamates and pyrethroids [4]. Organophosphates (OP) are a large and diverse class of chemicals that, especially in developed countries, continue to be one of the most important classes of anticholinesterase action insecticides still used [10]. Therefore, they have caused severe environmental pollution, which results in a significant health hazard to target and non-target organisms [11]. The absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of organophosphate compounds are studied in animals and humans [11, 12]. These compounds can cross the lipid double layers, due to their lipophilic characteristics, be absorbed and pass to the bloodstream from which they are distributed in different tissues, in particular in the adipose tissue. These compounds usually cannot accumulate due to rapid biodegradation [13]. Organophosphate pesticides (OPs) are mainly neurotoxic and their species selectivity is low [14, 15]. Moreover, pesticides, as endocrine disruptors, can interact with the action of modulating molecules such as steroid and thyroid hormones, which have a decisive physiological role in the maturation of specific brain areas, involved in the regulation of complex behaviours and reproductive functions.

Biological tests conducted on sea urchins offer endpoints of fertilization and larval development [16–20]. Paracentrotus lividus is an echinoderm widely distributed throughout the Mediterranean Sea; it inhabits a broad range of substrates from rocks and boulders, to sea grass meadows or maerl beds, and lives from the low-water limit down to about 20 m depth [21]. P. lividus has found wide application in the ecotoxicological studies, especially in the study of the effects of different substances on embryonic development (developmental defects and mitotic aberrations) [22].

Moreover, it’s a model organism for assessment of sea water quality [23], ecology [24], developmental biology [25], embryology and biomineralization processes [26]. It is representative of both benthonic (adult specimens) and planktonic (embryos and larvae) marine organisms; it also lives in shallow sea water near the coast, the marine sites that are most impacted by human activities [27]. P. lividus may develop at salinities as high as 38% in Mediterranean areas [28] and their gametes remain particularly sensitive to reduced salinity despite acclimatization of the adults [29].

P. lividus gametes are more sensitive to organic pollution than adults [30–33], so in the present study we have investigated the adverse effects of dimethoate, pesticide belonging to the organophosphate class (OP), on fertilization and on the embryonic development of P. lividus, so as to define its concentration and effects.

Methods and Materials

Preparation of dimethoate solutions

We used commercial dimethoate used for the protection of citrus fruits, vegetables, wheat and ornamental plants grown in greenhouses. It is marketed as an emulsion with a concentration of 37%. For experimental phase a stock solution consisting of 1 ml of the pesticide diluted in 9 ml of seawater was prepared, with a concentration of 0.04 g/10 ml (4 × 10−2 g/10 ml). Starting from this stock solution, through the scalar dilutions, we have obtained and used the following concentrations: 4 × 10−3, 4 × 10−4, 4 × 10−5, 4 × 10−6 and 4 × 10−7 g/10 ml.

Experimental section

The experiment was conducted on specimens of P. lividus supplied by local fishermen. Adult sea urchins (P. lividus) were taken to the laboratory of University of Catania in seawater tanks within 1 h of collection. We maintained them in a recirculating sea-water aquarium with the temperature regulated close to natural environmental conditions [34]. Therefore, the animals were dissected and the coelomic cavity has been washed with sea water; subsequently the male specimens were separated from the female ones. The eggs and the sperm were collected directly from the animal’s gonads mechanically in individual beakers. A total of 10 individuals were collected to have a considerable proportion of males and females (n = 5 males and n = 5 females). The gametes have been preliminarily observed under a microscope to evaluate their quality. Dry’s spermatozoa and egg cells were then added to 50 ml Falcon® containing seawater, filtered through 0.45 μm membrane filters to remove suspended solids. The Falcon® has been placed on an orbital shaker to maintain constant oxygenation. A part of the solution containing the male gametes has been joined to that containing the female gametes in order to favour fertilization. Fertilization success was checked under the microscope, only batches of embryos exhibiting >90% successful fertilization were used for subsequent embryotoxicity test [35]. We have obtained control sample of spermatozoa, egg cells and zygotes. Using the above-mentioned dimethoate solutions, we determined its toxicity, according to experimental design in Fig. 1A and B. Duplicate experiments were conducted.

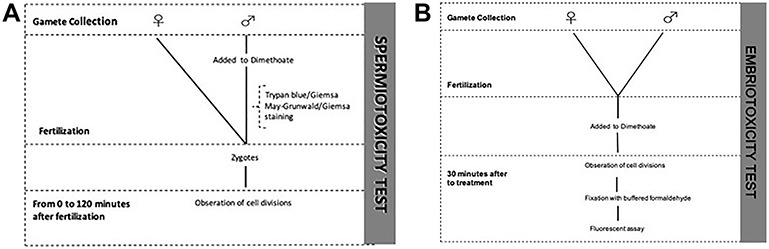

Figure 1.

Experimental design; (A) spermiotoxicity test; (B) embriotoxicity test.

Spermiotoxicity test

To study the effects of dimethoate on sperm viability, 2 ml of sperm dilution were added to dimethoate’s solutions in individual beakers (4 × 10−3, 4 × 10−4, 4 × 10−5, 4 × 10−6 and 4 × 10−7 g/10 ml), then after 30 min eggs cell untreated were added to verify the spermatozoas’s fertilizing capacity. Fertilization was allowed to take place for 30 min, then slides were prepared for the observation of fresh preparations. We have obtained zygote samples by fertilization of spermatozoa contaminates. The cell divisions were observed at 0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 90 and 120 min after fertilization by an optical microscope.

Trypan blue/Giemsa and May−Grunwald/Giemsa staining

After exposing sperm to dimethoate for 20 min, we evaluated the effect of dimethoate on sperm vitality and on the integrity of the acrosome vesicle using staining Trypan blue/Giemsa. We used Trypan blue at concentration of 0.27% and Giemsa solution at 7,5%. One drop of sperm (10 μl) and one drop of Trypan Blue (10 μl) were mixed on a slide, then a smear was made along the slide, we have prepared several slides. Slides were air-dried, then vertically put into a slide jar containing a fixative solution (43 ml of HCl 1 N + 7 ml of Formalin 37% + 0.1 g of azocarminium) for 2 min and then rinsed with distilled water. Slides were put into jars containing the Giemsa solution and placed at 37°C for 2 h. Slides were rinsed in tap water, in distilled water again so air-dried in vertical position and coverslipped with Entellan (Bio-Optica). Dead spermatozoa stained dark blue while live spermatozoa appeared pink [36]. Because this method also allows the evaluation of the acrosome features, intact acrosomes were purple, loose and damaged acrosomes were lavender, and the anterior part of the sperm head with no acrosome was pale gray. Live cells have sky-bluish postacrosomal region while dead cells are dark blue [37]. The term ‘live sperm’ indicated spermatozoa with intact membrane while ‘dead sperm’ those with disrupted membrane as it is considered more appropriate to refer to the membrane intactness [38]. The slides were examined by bright field microscopy at ×400 magnification.

Sperm morphology was assessed using staining May− Grunwald/Giemsa to observe whether treatment with dimethoate has caused morphological abnormalities. We used May−Grunwald (Bio-Optica) and Giemsa (Bio-Optica); we diluted 1:2 the Giemsa stock solution with distilled water. One drop of sperm (10 μl) was crawled along the slide and then air-dried. On the smear were added 7 drops of May−Grunwald and 14 drops of distilled water (to respect the ratio 1:2 between dye and distilled water) for 7 min. Then, this was drained and the Giemsa solution was added to cover the entire smear, for 7 min. Slides were rinsed in distilled water and air-dried in vertical position and coverslipped with Entellan (Bio-Optica). We observed the slides with a bright field microscope at ×400 magnification.

Embryotoxicity test

For the embryotoxicity test, sea urchin egg and sperm suspensions were mixed, and a period of 20 min was allowed for fertilization. The zygotes were observed under a microscope to evaluate their quality, and then exposed to the solutions of dimethoate for 30 min at room temperature.

At the end of the experiment, samples were immobilized with buffered formalin to be used for the fluorescent assay.

Fluorescent assay

Preparations for fluorescence microscopy have been made to assess DNA integrity. We used Dapi (Abcam) an organic fluorescent intercalator for DNA, often used for in situ hybridization techniques or other methods in which DNA fluorescence is required.

The blastules were fixed with 4% buffered formaldehyde for 10 min, washed with PBS and then centrifuged. A drop of the pellet containing the blastules was placed on a glass slide, then Dapi was added and mounted coverslips with rubber cement. Observations were carried out using a fluorescence microscope (NIKON ECLIPSE Ci), equipped with camera NIKON DS-Qi2. Dapi excites at 360 nm and emits at 460 nm, producing a blue fluorescence.

Statistical analysis of data

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using student’s t-test to test difference between the control and each experimental group.

Results

Spermiotoxicity

Spermatozoa contaminated with the different concentrations of dimethoate tested (4 × 10−3, 4 × 10−4, 4 × 10−5, 4 × 10−6 and 4 × 10−7 g/10 ml) showed no morphological abnormalities and alterations in the acrosomal vesicle. The May−Grunwald/Giemsa stain did not show any differences in the head, mid-connecting piece and tail of the spermatozoa compared to the controls (Fig. 2). Furthermore, staining with Trypan blue/Giemsa showed an intact acrosome such as controls thus the treatment with the pesticide had not damaged the acrosomal vesicle of the spermatozoa, which maintained their fertilizing capacity (Fig. 3). Therefore, through our spermiotoxicity tests we have shown that dimethoate solutions do not have a complete toxic effect, because the treated spermatozoa were able to fertilize eggs cell untreated. Fertilizing ability did not appear to be affected by any dimethoate concentration tested (Fig. 4).

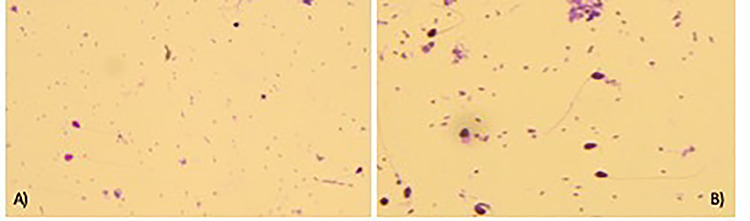

Figure 2.

May−Grunwald/Giemsa staining; (A) control spermatozoa; (B) spermatozoa treated with dimethoate 0.000004 g/10 ml; ×400 optical microscope.

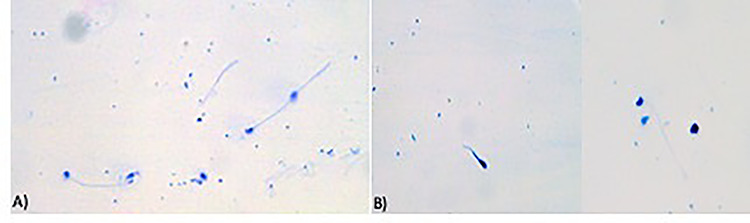

Figure 3.

Trypan blue/Giemsa staining; (A) control spermatozoa; (B) spermatozoa treated with dimethoate 0.000004 g/10 ml; ×400 optical microscope.

Figure 4.

Effects of different concentrations of dimethoate on fertilization of P. lividus.

Embriotoxicity

Untreated eggs cell fertilizated by treated sperm showed alterations in the planes of division from the earliest stages of segmentation. They appeared to be irregular and asynchronous, compared to the control already on exposure at low doses (4 × 10−6 g/10 ml) (Fig. 5A−C). Anyway, the embryo development carries on and the rate of fertilization was not significantly reduced in the groups exposed also at the high concentration of dimethoate (Fig. 6). Also the zygotes, obtained by eggs cell and spermatozoa untreated, after exposition at dimethoate solutions (4 × 10−4 g/10 ml, 4 × ×10−5 g/10 ml) showed alterations in the segmentation planes: asynchronous, asymmetric with partial cytoplasmic divisions. In addition, blastomeres lost their close contact (Fig. 7) and fluorescent assay have shown a DNA fragmentation compared to control (Fig. 8A−C).

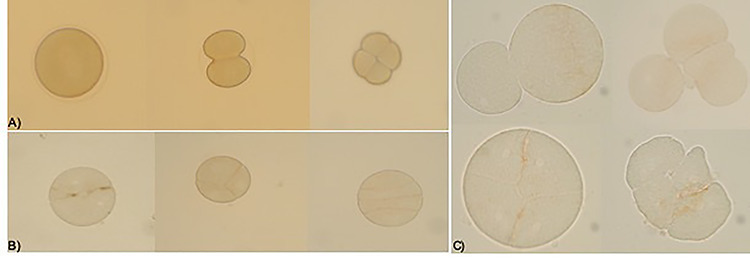

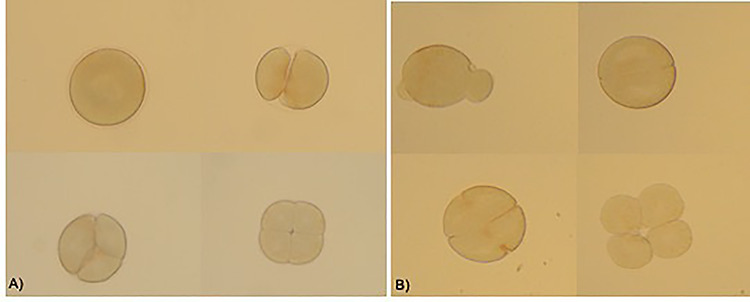

Figure 5.

Effects on fertilization of untreated egg cells by treated spermatozoa; (A) control; (B) the planes of division are not regular and appear asynchronous for egg cells fertilized by treated spermatozoa with dimethoate 0.000004 g/10 ml; ×200 Optical microscope; (C) detail of the anomalies during the segmentation 0.000004 g/10 ml dimethoate; ×400 optical microscope.

Figure 6.

Effects of different concentrations of dimethoate on early development of P. lividus.

Figure 7.

Effects on zygotes’ segmentation exposed to different concentrations of dimethoate; the segmentation appeared altered in (A) zygotes exposed to 0.0004 g/10 ml dimethoate (B) zygotes exposed to 0.00004 g/10 ml; ×200 optical microscope.

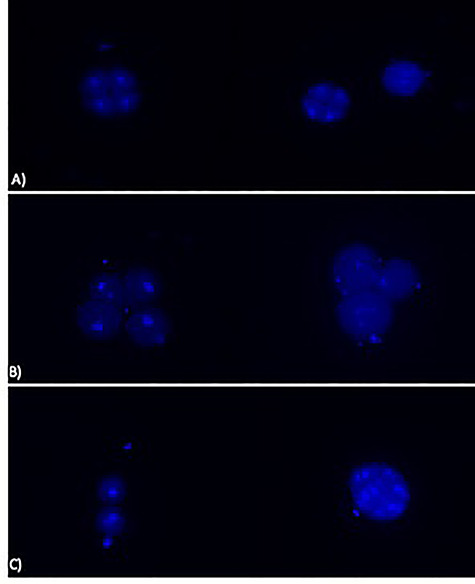

Figure 8.

Effects of dimethoate on DNA fragmentation (A) control (B) in zygotes exposed to 0.0004 g/10 ml dimethoate (C) in zygotes exposed to 0.00004 g/10 ml dimethoate; ×200 fluorescence microscope.

Discussions

Exposure to contaminants can induce deleterious effects to aquatic organisms menacing their health and affecting the ecosystem [39–41]. Current strategies of water quality assessment integrate the chemical analysis with biological parameters to evaluate the effects of pollution on living resources [42, 43]. Exposure to dimethoate may represent a risk to organism and aquatic environment due to its high solubility in water [44, 45]. Exposure studies on aquatic organisms revealed an altered swimming behaviour, increased gulping for air and increased mucus secretion over the body [46]. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the toxicity of dimethoate on fertilization and early development. Although eurytopic species, with a wide tolerance to environmental changes (including estuarine molluscs, worms and crustaceans), are more suited for environmental quality assessment than stenotopic species with narrow tolerance [47], sea urchin sperm and embryo-larval bioassays have been routinely used for water quality assessment for decades due to the sensitivity of gametes and early stages of development to pollutants present in seawater, even at very low concentrations [42, 48, 49]. The choice of species may depend on practical considerations, such as the availability of mature adults for the tests for example gametes can be obtained from P. lividus easily by KCl injection, and plutei can be obtained. Moreover, it may also depend on the characteristics of the area to be monitored: bivalve larvae are preferable when assessing the environmental quality in coastal waters and particularly in shellfish farming areas, and sea urchins should be used for offshore waters [50].

In this study, we analysed the effects of dimethoate on sea urchin P. lividus development; not previously investigated. We found that exposing sea urchin sperm to different concentration of dimethoate does not affect their fertilizing ability but can cause irreversible developmental anomalies in the offspring because we have observed alteration at the early stage of the development such as asymmetric and/or asynchronous cell divisions. Previous studies have shown that the basudin (an organophosphate compound containing 20% Diazinon) has a toxicity effect on the early phases of sea urchin development with a delayed the early mitotic cycles when suspensions are added to unsterilized eggs [51]. Also the permethrin, a pyrethroid that has replaced the organophosphorus and is widely used, has showed spermiotoxicity and embryotoxicity on P. lividus. It has been shown that exposure to relatively low concentrations of permethrin can cause deleterious effects more to embryos than to sperm of P. lividus [52]. Similar results were obtained by Gharred et al. [53], who investigated the toxicity of another pyrethroid, Deltamethrin, and found that exposure of zygotes, from untreated gametes, to low concentrations caused asymmetric and/or asynchronous cell divisions and partial cytoplasmic divisions as we have observed for exposure to dimethoate. Moreover, preparations for fluorescence microscopy showed the nuclei of dividing cells, which were regular in the controls, while the treated samples showed fragmented with numerous micronuclei, thus demonstrating that dimethoate is mutagenic. A study carried out on mice demonstrated that dimethoate induced DNA damage in the liver and kidney in a dose-dependent manner; this induction was associated to DM-induced oxidative stress [54].

Conclusion

These data suggest that dimethoate does not have an effect on the reproductive success of P.lividus in the early stages, but the mutagenic activity of dimethoate could compromise ability to arrive at adult stage; therefore, the survival of the species can be compromised. These results can provide useful suggestions for the prevention of environmental contaminants that reduces the reproductive capacity of aquatic organisms.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a grant from University of Catania (Piano per la Ricerca 2016/2018). S.I. thanks Industrial PhD programme (PON RICERCA ED INNOVAZIONE 2014−2020).

References

- 1. Casida JE, Bryant RJ. The ABCs of pesticide toxicology: amounts, biology, and chemistry. Toxicol Res 2017;6:755–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Iyaniwura TT. Health and environmental hazards of pesticides. Rev Environ Health 1991;9:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aktar W, Sengupta D, Chowdhury A. Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: their benefits and hazards. Interdiscip Toxicol 2009;2:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Özkara A., Akyıl D. and Konuk M., Pesticides, environmental pollution, and health In: Larramendy ML, Soloneski S (eds). Environmental Health Risk-Hazardous Factors to Living Species. London, UK: IntechOpen, 2016, DOI: 10.5772/63094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Regulation (UE) n. 62 - replacing Annex I to Regulation (EC) n. 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council. 2018.

- 6. Nagaraju B, Rathnamma VV. Gas liquid chromatography-flame ionization detector (GLC-FID) residue analysis of carbamate pesticide in freshwater fish Labeo rohita. Toxicol Res 2014;3:177–83. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Williamson S., Understanding the full costs of pesticides: experience from the field with a focus on Africa In: Stoytcheva M (ed). Pesticides-The Impacts Of Pesticides Exposure. Rijeka, Croatia: IntechOpen, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Regulation (CE) of the European Parliament and of the Council n. 1107 relating to the placing on the market of plant protection products and repealing the Council directives 79/117/CEE e 91/414/CEE. 2009.

- 9. Regulation (EU) n. 528 of the European Parliament and of the Council relating to the making available on the market and the use of biocidal products. 2012.

- 10. Mangas I, Vilanova E, Estévez J et al. Neurotoxic effects associated with current uses of organophosphorus compounds. J Braz Chem Soc 2016;27:809–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akbel E, Arslan-Acaroz D, Demirel HH et al. The subchronic exposure to malathion, an organophosphate pesticide, causes lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress, and tissue damage in rats: the protective role of resveratrol. Toxicol Res 2018;7:503–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poet TS, Kousba AA, Dennison SL et al. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model for the organophosphorus pesticide diazinon. Neurotoxicology 2004;25:1013–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Costa LG, McDonald BE, Murphy SD et al. Serum paraoxonase and its influence on paraoxon and chlorpyrifos-oxon toxicity in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1990;103:66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aldridge WN. Organophosphorus compounds: molecular basis for their biological properties. Sci Prog 1981;67:131–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Costa LG. The neurotoxicity of organochlorine and pyrethroid pesticides. Handbook of clinical neurology Elsevier 2015;131:135–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. His E, Beiras R, Seaman M. The assessment of aquatic contamination: bioassays with bivalve larvae. Adv Mar Biol 1999;37:1–178. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kobayashi N, Okamura H. Effects of new antifouling compounds on the development of sea urchin. Mar Pollut Bull 2002;44:748–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Manzo S. Sea urchin embryotoxicity test: proposal for a simplified bioassay. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2004;57:123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pagano G, His E, Beiras R et al. Cytogenetic, developmental, and biochemical effects of aluminium, iron, and their mixture in sea urchins and mussels. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 1996;31:466–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manzo S, Buono S, Cremisini C. Toxic effects of irgarol and diuron on sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus early development, fertilization, and offspring quality. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2006;51:61–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bayed A, Quiniou F, Benrha A et al. The Paracentrotus lividus populations from the northern Moroccan Atlantic coast: growth, reproduction and health condition. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 2005;85:999–1007. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sartori D, Macchia S, Vitiello V et al. ISPRA. Rome, Italy: Quaderni–Ricerca Marina n. 11, 2017, 60. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kobayashi N. Marine pollution bioassay by using sea urchin eggs in the Tanabe bay, Wakayama prefecture, Japan, 1970-1987. Marine Poll Bull 1991;23:709–13. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kroeker KJ, Kordas RL, Crim RN et al. Meta-analysis reveals negative yet variable effects of ocean acidification on marine organisms. Ecol Lett 2010;14:E1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jasny BR, Prunell BA. The glorious sea urchin-introduction. Science 2006;314:938.17095688 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilt FH. Developmental biology meets materials science: morphogenesis of biomineralized structures. Dev Biol 2005;280:15e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gambardella C, Aluigi MG, Ferrando S et al. Developmental abnormalities and changes in cholinesterase activity in sea urchin embryos and larvae from sperm exposed to engineered nanoparticles. Aquat Toxicol 2013;30:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Warnau M., Iacarino M., Biase A., et al. Pagano Spermiotoxicity and embryotoxicity of heavy metals in the echinoid P. lividus, Environ Toxicol Chem, 1996, 15, 1931±1936. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dinnel PA, Link JM, Strober AJ. Improved methodology for a sea urchin sperm cell bioassay for marine water. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol USA 1987;16:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tortonese E. Echinodermata. Fauna d’Italia. Edizioni Calderini 1965;53:422. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Allain JY. Structure des populations de Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck) (Echinodermata, Echinoidea) soumises à la pêche sur les côtes Nord de Bretagne. Rev. trav. Inst pêches marit 1975;39:171–212. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zavodnik D. Synopsis of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816) in the Adriatic Sea Colloque international sur Paracentrotus lividus et les oursins comestibles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1987, 221–240. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Delmas P., Etude des populations de Paracentrotus lividus (Lam.) (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) soumises à une pollution complexe en Provence nord-occidentale: densités, structure, processus de détoxication (Zn, Cu, Pb, Cd, Fe), PhD Thesis. Aix-Marseille 3, 1992.

- 34. Greenwood PJ. The influence of an oil dispersant chemserve OSE-DH on the viability of sea urchin gametes. Combined effects of temperature, concentration and exposure time on fertilization. Aquat Toxicol 1983;4:15–29. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu B, Torres-Duarte C, Cole BJ et al. Copper oxide and zinc oxide nanomaterials act as inhibitors of multidrug resistance transport in sea urchin embryos: their role as chemosensitizers. Environ Sci Technol 2015;49:5760–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Serafini R, Longobardi V, Spadetta M et al. Trypan blue/giemsa staining to assess sperm membrane integrity in salernitano stallions and its relationship to pregnancy rates. Reprod Domest Anim 2014;49:41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kovàcs A., Foote R., Nagy S., et al. Live/dead and acrosome staining of stallion spermatozoa In: 14th International Congress on Animal Reproduction- Stockholm. Stockholm, Sweden: Elsevier, 2000, 82. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Love CC. Measurement of concentration and viability in stallion sperm. J equine vet sci 2012;32:464–6. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Antwi FB, Reddy GVP. Toxicological effects of pyrethroids on non-target aquatic insects. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2015;40:915–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abdel-Shafy HI, Mansour MSM. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydro- carbons: source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egypt J Pet 2016;25:107–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Torres T, Cunha I, Martins R et al. Screening the toxicity of selected personal care products using embryo bioassays: 4-MBC, propylparaben and triclocarban. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beiras R, Fernandez N, Bellas J et al. Integrative assessment of marine pollution in Galician estuaries using sediment chemistry, mussel bioaccumulation, and embryo-larval toxicity bioassays. Chemosphere 2003;52:1209–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bellas J, Fernandez N, Lorenzo I et al. Integrative assessment of coastal pollution in Ría coastal system (Galicia, NW Spain): correspondence between sediment chemistry and toxicit. Chemosphere 2008;72:826–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. PPDB The Pesticide Properties Database. http://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/244 (September 2016, date last accessed).

- 45. National Pesticide Information Center (NPIC) OSU Extension Pesticide Properties Data- base. http://npic.orst.edu/ingred/ppdmove.htm (November 2019, date last accessed).

- 46. Pandey RK, Singh RN, Singh S et al. Acute toxicity bioassay of dimethoate on freshwater airbreathing catfish, Heteropneustes fossilis (Bloch). J Environ Biol 2009;30:437–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Moriarty F. Ecotoxicology: The Study of Pollutants in Ecosystems. London: Academic Press, 1990, 289. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dinnel PA, Link JM, Stober QJ et al. Comparatives sensitivity of sea urchin sperm bioassays to metals and pesticides. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 1989;18:748–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Paredes E, Bellas J. The use of cryopreserved sea urchin embryos (Paracentrotus lividus) in marine quality assessment. Chemosphere 2015;128:278–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. His E, Heyvang I, Geffard O et al. A comparison between oyster (Crassostrea gigas) and sea urchin (Paracentrotus lividus) larval bioassays for toxicological studies. Water Res 1999;33:1706–18. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pesando D, Huitorel P, Dolcini V et al. Biological targets of neurotoxic pesticides analysed by alteration of developmental events in the Mediterranean Sea urchin, Paracentrotus lividus. Mar Environ Res 2003;55:39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Erkmen B. Spermiotoxicity and embryotoxicity of permethrin in the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2015;94:419–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gharred T, Ezzine IK, Naija A et al. Assessment of toxic interactions between deltamethrin and copper on the fertility and developmental events in the Mediterranean Sea urchin, Paracentrotus lividus. Environ Monit Assess 2015;187:193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ayed-Boussema I, Rjiba K, Moussa A et al. Genotoxicity associated with oxidative damage in the liver and kidney of mice exposed to dimethoate subchronic intoxication. Environ Sci Pollut R 2012;19:458–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]