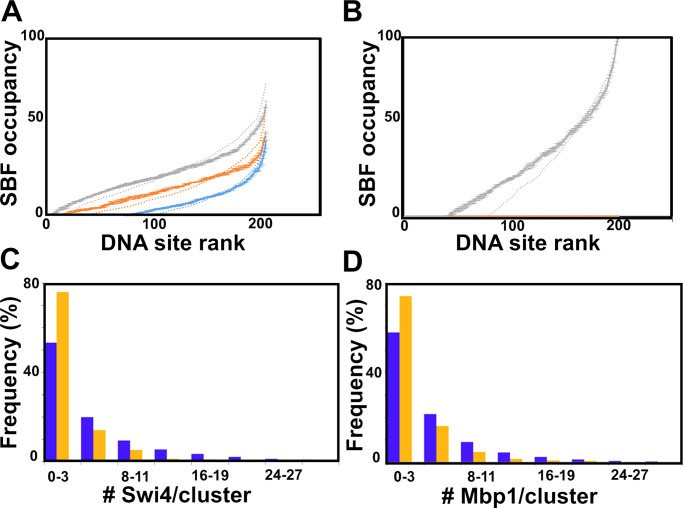

Figure 7.

Clustering improves DNA simulated site occupancy and synchrony, while Swi6 contributes to experimental Swi4 and Mbp1 clustering. (A) Clustering homogenizes DNA occupancy. Promoters are ranked by SBF occupancy. Promoter occupancy by SBF is represented as fraction of time in the steady-state (vertical axis, percent of 5 s test time) during which each individual G1/S promoter (represented by individual dots) is occupied by SBF in small (blue; cell volume = 10 fl), medium size (orange; cell volume = 17 fl), and large (gray; cell volume = 31.5 fl) cells. To facilitate data visualization, promoters were ranked according to increasing occupancy, which was averaged at each ranking position (rather than each individual promoter) over five simulations conducted in the presence of G1/S promoter clusters. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Promoter occupancy is defined similarly but in the absence of G1/S promoter clustering is shown as dotted lines for comparison. (B) Clustering improves Start synchrony. Promoter SBF occupancy represented as fractions of time in the steady-state (vertical axis, percent of short 1 s test time) as in A in large cells (i.e., close to the G1/S transition). As in A, promoters were ranked according to increasing SBF occupancy, which was averaged at each ranking position over five simulations conducted in the presence of G1/S promoter clusters. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Promoter occupancy defined similarly but in the absence of G1/S promoter clustering (and thus, TF clustering; see Fig. S2, C and E) is shown as a dotted line for comparison. The number of promoters that are never SBF-bound during this critical time where the cell is susceptible to trigger Start at any time is twofold larger in the absence of clustering, indicating that clustering may improve Start synchrony. (C and D) Histograms of the number of (C) Swi4 molecules per cluster and (D) the number of Mbp1 molecules per cluster in WT (purple) and swi6Δ (orange) cells.