Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the differences in distribution of intracapsular and extracapsular hip fractures among genders and age groups treated surgically.

Materials and methods: This is a nine-year retrospective cohort study. The type of hip fractures, age, and sex-related as well as overall incidence among 2 430 patients aged over 65, surgically treated at the “Venizeleio” General Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece, were explored and evaluated.

Outcomes: Women suffered hip fractures 2.9 times more often than men. The majority of patients hospitalized with hip fracture were above 75 years of age (62.3% in females and 59.3% in males). The proportion of extracapsular and intracapsular fractures were 59.6% and 40.4% in men and 62.7% and 37.2% in women, respectively. Extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures were found to increase dramatically with age in women (from 52.3% in patients younger than 75 to 58.8% in those older than 75; p-value=0.007), while in men they slightly increased with age (57.7% in patients older than 75, compared to 55.7% in those less than 75; p-value=0.62).

Conclusion: The pattern of hip fractures was found to differ between genders and age groups in the present patients’ population. Most likely, these findings reflect differences in the nature and rate of bone loss, and frequency of falling events between males and females. It has become evident that the two main hip fracture types (extracapsular and intracapsular) are distinct clinical entities. Hence, they should be addressed independently in terms of underlying causes and prevention strategies.

Keywords:hip fractures, gender differences, Southern Europe, Crete, Greece.

INTRODUCTION

Hip fractures are considered a principal cause of morbidity and mortality among patients over the age of 65 years. The main cause of this injury is low energy ground level falls (1). They represent a major cause of hospitalization among the elderly, and a major public health issue with significant personal, social and financial impact in the Western societies (2, 3).

Many studies have grouped hip fractures as a homogeneous condition, though there are two major anatomical types: those defined as intracapsular and those defined as extracapsular. Intracapsular fractures occur in the region from just above the intertrochanteric region to just below the articular surface of the femoral neck. The group of extracapsular fractures consists of intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric. The intertrochanteric region runs between the greater and lesser trochanter, whereas the subtrochanteric region is typically defined as the area extending from the lesser trochanter to a point 5 cm distally. Bone structure differs between these anatomical areas and intertrochanteric fractures are typically associated with osteoporosis. Recently published data indicate that there are substantial differences between patients suffering extracapsular-intertrochanteric and intracapsular hip fractures (4, 5). Hence, studies have shown that advanced age and osteoporosis is more strongly associated with the risk of extracapsular-intertrochanteric than intracapsular fractures (6). Sex, referring both to biological and social aspect, is a major decisive factor in many circumstances, but little is known about how sex affects falls and subsequent hip fractures in the elderly. The situation in Greece regarding age and gender specific incidence rates of intracapsular and extracapsular fractures, and the subsequent morbidity and mortality, as well as the size of the problem in general, remains unclear due to shortcomings in studies, information, and health system procedures.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the characteristics of patients with hip fractures, surgically treated during a nine- year period at the Orthopaedic Department of the “Venizeleio” General Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece. The study also aimed to further investigate the incidence of extracapsular and intracapsular fractures and how the proportion changes between genders with aging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The records of all patients, surgically treated for a hip fracture at the Orthopaedic Department of the “Venizeleio” General Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece, from January 2010 to December 2018, were retrospectively reviewed.

The Venizeleio” General Hospital of Heraklion, Crete is a 500-bed, secondary and tertiary hospital on the island of Crete, Greece. The population of the island (approximately 650,000) is mixed rural, urban and suburban. The present patient sample can be considered representative of the Cretan population.

All patients over the age of 65, diagnosed with hip fracture and surgically treated, were included in the study. Patients younger than 65, those suffering a fracture due to malignancy (pathological fracture), and multiple trauma patients were excluded.

Selected patients were divided into two age groups: “younger” (65-74 years old) and “older” (over 75) elderly. Fractures were also divided into two types: intracapsular and extracapsular. The latter were further divided into two subtypes: intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures. The correlation of type and subtype of fractures with gender and age has been examined.

Two-tailed hypothesis tests for two population proportions were carried out in order to further calculate the p-values, where distinct male/female groups were met. Additionally, two-tailed tests were used for calculating the p-values, where the mean ages of male/female groups were examined. Data are presented as numbers (%) for categorical variables and mean value ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. Statistical analysis was performed with Epiinfo version 7.1.2.0 (Center for Diseases Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA).

OUTCOMES

A total of 2 430 patients diagnosed with a hip fracture and surgically treated, who met the inclusion criteria, were identified during the study period. Both intracapsular and extracapsular fractures were much more frequentamong women [2.9 times more than men (622 males or 25.6% with mean age 77.07 years; standard deviation (SD)=10.2 and 1 808 females or 74.4% with mean age 81.25; SD=16.3)].

74.4% with mean age 81.25; SD=16.3)]. There were 1 490 (61.3%) extracapsular and 940 (38.7%) intracapsular fractures. Among extracapsular fractures, 1 373 (92%) were intertrochanteric and 117 (8%) subtrochanteric.

Among women, the mean age for extracapsular- intertrochanteric fractures was higher [82.15 years; standard deviation (SD)=9.4] compared to those with intracapsular fractures [80.14 years (SD=10.9); p<0.0001]. On the other hand, among men, the mean age for extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures was lower [76.6 years; SD=17.7] than mean with intracapsular fractures [78.9 years (SD=12.9); p=0.088].

Among 622 men, 390 (62.7%) suffered an extracapsular hip fracture. Extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures were observed in 354 (90.7%) male subjects and extracapsular-subtrochanteric in 36 (9.3%). The remaining 232 (37.3%) had an intracapsular fracture.

In females, extracapsular fracture was also the commonest, accounting for 1 100 (60.8%) of cases; 1 019 women suffered an extracap- sular-intertrochanteric fracture (92.6%) and 81 (7.4%) an extracapsular-subtrochanteric fracture.

Both females and males suffered significantly more often extracapsular-intertrochanteric than intracapsular fractures [59% (1 019) compared to 41% (708) in females and 60.4% (354) compared to 39.6% (232) in males, respectively; p<0.0001].

Both females and males suffered significantly more often extracapsular-intertrochanteric than intracapsular fractures [59% (1 019) compared to 41% (708) in females and 60.4% (354) compared to 39.6% (232) in males, respectively; p<0.0001].

The ratio of intertrochanteric/subcapital hip fractures in females was increased from 1.2 in the “younger” elderly to 1.6 in the “older” elderly, while this ratio was increased from 1.4 to 1.5 in males.

In male patients, the incidence of extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures in the “older” group was slightly but non-significantly higher (57.7% compared to 55.7% in “younger” elderly; p=0.62). Furthermore, a slightly but non-significantly lower incidence of extracapsular- subtrochanteric fractures was observed in the “older” (4.3%) compared to the “younger” male group (7.5%) (p=0.09). In female patients, the incidence of extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures was found to increase with age (58.80% in the “older” group compared to 52.3% in the “younger” group; p=0.007), while that of intracapsular fractures was decreased (36.5% in the “older” group compared to 43.7% in the “younger” group; p=0.002).

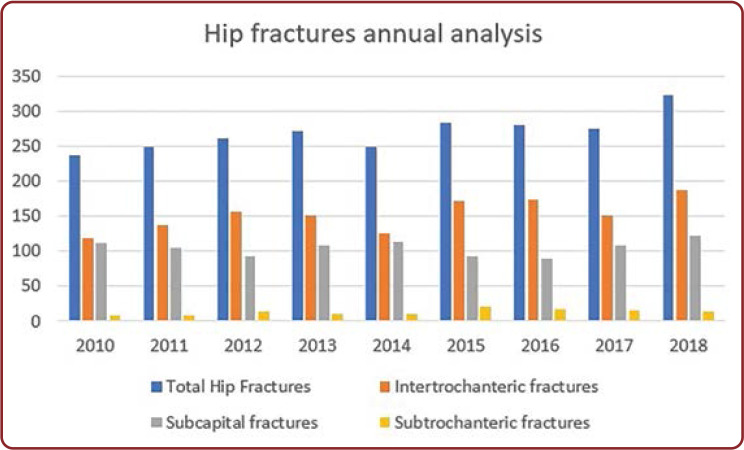

“younger” group; p=0.002). Furthermore, from 2010 to 2018 there was an increase of 36.29% in total hip fractures, 59.32% in intertrochanteric fractures, 9.91% in subcapital fractures and 38.46% in subtrochanteric fractures (Figure 1).

CONCLUSIONS

The main findings of the present study are that females and individuals older than 75 years of age were more likely to suffer a hip fracture. The incidence of the two types of fractures (intracapsular and extracapsular) was not equal, with a considerable predominance for the latter. Both females and males suffered more often extracapsular-intertrochanteric than intracapsular fractures. However, the distribution of fracture type was different between genders across age groups. Among women there is a sharp increase in the ratio of intertrochanteric/subcapital hip fractures with advanced age, while o slight increase is observed in males.

These findings confirmed that the incidence of hip fractures was higher in the “older” elderly than the “younger” ones. Older people suffer more severe osteoporosis and have a more frequent falling record (7). Bone mass gradually declines with age and consequently, the incidence of osteoporosis increases (8), the prevalence of hip fracture increasing with age. Studies have shown a two-fold increase of fracture rate in each decade of life after the age of 50, and by the age of 90, 32% of women and 17% of men would have suffered a hip fracture in the US (9). The 10-year risk of hip fracture for women in UK raises from 0.3% at the age of 50, to 8.7% at the age of 80 (6).

The overall female-to-male incidence ratio of hip fracture in the present study was 2.9, which is consistent with the published literature (10). Epidemiological studies have shown that the number of extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures progressively increased with age, mainly in women after menopause as compared to intracapsular fractures (11, 12).

A significant increase in the frequency of extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures among female subjects of the present study occurred with increasing age. The proportion of extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures in the present women climbed from 52.3% in “younger” to 58.8% in “older” group. Our findings regarding the escalation of incidence of extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures with increasing age among women were comparable to those of previous studies in North American and Norwegian populations (5, 13, 14). One in three women and one in eight men aged above 50 were reported to have osteoporosis. This fact, in combination with the longer life expectancy for women, may explain their increased risk for hip fractures (15).

Lower bone mass density, due to the remarkable increase of the Western populations’ life expectancy, is the predominant reason for the growing incidence of extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures. In patients with hip fractures, trabecular weakening substantially contributes to further bone loss upon pre-existing age-related osteoporosis (16). When hip axis length and bone mineral density were measured in specific regions of the lower and upper part of the femoral neck to determine whether these parameters were significant predictors of the type of hip fracture, it came up that intracapsular and extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures could be predicted based on different morphometric and densitometric features of the femoral neck (17). It has been found that hip fractures were uncommon among women with femoral neck bone density greater than or equal to 1.0 g/cm2. The prevalence of intracapsular hip fracture was 8.3 per 1,000 person-years among women with femoral neck bone density less than 0.6 g/cm2, while the estimated incidence of extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures was double among those with intertrochanteric bone density less than 0.6 g/cm2 (18). There is evidence that loss of trabecular and cortical bone with age may differ between men and women (19). Most Caucasian women under the age of 50 have normal bone density, whereas by the age of 80 nearly 70% of them are osteoporotic and 30% osteopenic (8).

The present study has found that, unlike females, among males there has been a slight increase in the proportion of intracapsular fractures with age. Consequently, the incidence of extracapsular-intertrochanteric fractures shows a trivial rise in the “older” male group, assuming that, among men, osteoporosis might not be strongly associated with hip fractures. This may also reflect a higher frequency of high energy injuries due to more intense physical activity. There is evidence that younger and stronger elderly males may possibly take more risks, or be more active beyond their abilities (20, 21).

Hip fractures in elderly may not always be associated with osteoporosis. Previous studies have raised the question that, in certain populations, falling and not osteoporosis was the main cause of hip fracture (19, 22). The type of fracture (intracapsular or extracapsular) also depends on the angle impact of the greater trochanter at the moment of contact with the floor (23).

The characteristics of the fall event may define the type of fracture, whereas bone mineral density and other factors that increase or decrease the effect of the fall determine whether a fracture will occur when a faller lands on a particular bone (24). It is possible that the fall characteristics of the elderly may have changed during the last decades, resulting in an increase of extracapsular-intertrochanteric hip fractures.

For reasons that are not entirely agreed upon, hip fractures, osteoarthritis, and the most predominant musculoskeletal disorders, including osteoporosis and excessive bone mass loss in elderly, are found more often in females. This appears to be related to hormonal transitions at the time of menopause, but other explanations might also exist (25, 26). The overrepresentation of women in our study could be due to localized differences in bone density at specific sites of the proximal femur among females and the greater frequency of falling. Female gender is an independent risk factor for falls, since a higher incidence of fallers among all age groups are women in several studies (23). Reduced postural control of women under stressing balance may explain the higher incidence of falling (27). Female muscles waste faster than the male ones, especially after menopause. Additionally, women usually experience more sedentary lifestyle and poorer nutrition than men affecting the bone density and fragility of their skeleton (25).

The influence of physical activity in middle age women in association with the subsequent risk of suffering a hip fracture has been extensively studied. Researchers have concluded that an active life style in middle age reduced the risk of fracture, probably due to improved muscle strength, coordination and balance reducing the risk of falling (28).

However, other issues may also be important. Socioeconomic factors have significant consequences on the health of older women (25, 26). Compared to men, elderly women are recorded more often to suffer mental illness such as depression, and have a greater tendency to use multiple medications, which is a well-known risk factor for falls (29).

It is also of note that a total increase of 36.29% was observed in hip fractures during the nine-year study period. This could also be attributed to the effects of the financial crisis in Greece during these years. The majority of patients during the crisis are seeking medical and surgical care in public institutions (30). Furthermore, intertrochanteric fractures showed a vast increase of 59.32%, while subcapital fractures just a slight increase of 9.91%. A possible explanation may be untreated osteoporosis, which is associated more with intertrochanteric fractures than subcapital ones. Awareness and treatment of osteoporosis may have been affected during the Greek crisis, while no data exist regarding this matter.

The present research is the first study evaluating characteristics and epidemiology of hip fractures in patients undergoing surgical treatment in the Cretan population and one of the few such studies from South-Eastern Europe. The present findings have shown that the pattern of hip fractures among Cretan elderly is not different from other Western societies, despite some particular “Mediterranean characteristics” of the study population. The geographical area is important for the epidemiology and incidence of hip fractures, since they are affected by life expectancy, social habits and local cultures that differ substantially between different regions.

The present study has some limitations. It is a retrospective cohort study. Although our sample is considered representative of the Cretan population, it did not include geographically the whole island. Also, patients with non-surgically treated hip fracture were excluded (in such cases, surgery either was not needed or could not be performed). Therefore, our findings may not be able to address the absolute risk of hip fracture and the incidence of this injury in elderly Cretans might be underestimated.

All factors leading to these findings are not totally clear, since the described differences across various age groups seem to be multifactorial. Although substantial research of parameters, risk factors and interventions to reduce hip fractures among elderly has been performed, there are still some unclear areas in this field requiring further investigation, especially in Eastern and Southern European elderly population.

The present study sketched the epidemiology of hip fractures treated surgically in the “Venizeleio” General Hospital of Crete, Greece, from 2010 to 2018. The study’s findings describe hip fractures in this area of Europe, including the different fracture type in males and females, the higher prevalence of intertrochanteric fracture in females than males, and the dramatic increase of incidence in patients older than 75 years in both genders. These findings advocate the heterogeneity of these injuries and are suggesting that a complete understanding of the etiology and mechanisms of different types of fractures may entail separate study of fracture subtypes. Consequently, the development and implementation of preventive interventions should focus on these factors and actions should be taken to target different elderly populations.

Conflict of interests: none declared

Financial support: none declared

FIGURE 1.

Per year-hip fracture analysis

Contributor Information

Kalliopi ALPANTAKI, Department of Orthopaedics, “Venizeleio” General Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Chrysoula PAPADAKI, “Venizeleio” General Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Konstantinos RAPTIS, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, “251” Hellenic Air Force General Hospital of Athens, Greece.

Konstantinos DRETAKIS, 2nd Orthopaedic Department, “Hygeia” General Hospital of Athens, Greece.

George SAMONIS, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Christos KOUTSERIMPAS, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, “251” Hellenic Air Force General Hospital of Athens, Greece.

References

- 1.Johnell O, Kanis J. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:s3–s7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang KP, Center JR, Nguyen TV, et al. Incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures in elderly men and women: Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research. 2004;19:532–536. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koutserimpas C, Samonis G, Vrentzos E, et al. In-hospital falls in older patients: A prospective study at the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece. Australas J Ageing. 2016;35:64. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mautalen CA, Vega EM, Einhorn TA. Are the etiologies of cervical and trochanteric hip fractures different? Bone. 1996;18:133. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanner DA, Kloseck M, Crilly RG, et al. Hip fracture types in men and women change differently with age. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimai HP, Svedbom A, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, et al. Epidemiology of hip fractures in Austria: evidence for a change in the secular trend. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:685–692. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez AA, Cuenca J, Panisello JJ, et al. Changes in the morphology of hip fractures within a 10-year period. J Bone Miner Metab. 2001;19:378–381. doi: 10.1007/s007740170008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfeilschifter J, Cooper C, Watts NB, et al. Regional and age-related variations in the proportions of hip fractures and major fractures among postmenopausal women: the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women. Osteoporos Int. 2012;8:2179–2188. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1840-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher JC, Melton LJ, Riggs BL, et al. Epidemiology of fractures of the proximal femur in Rochester, Minnesota. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;150:163–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;14:1573–1579. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baudoin C, Fardellone P, Sebert JL. Effect of sex and age on the ratio of cervical to trochanteric hip fracture. A meta-analysis of 15 reports on 36,451 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:647–653. doi: 10.3109/17453679308994590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinton RY, Smith GS. The association of age, race, and sex with the location of proximal femoral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:752–759. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199305000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pages A, Carbonell C, Fina F et al. Burden of osteoporotic fractures in primary health care in Catalonia (Spain): a population-based study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjorgul K, Reikeras O. Incidence of hip fracture in Southeastern Norway. Int Orthopaedics. 2007;31:3665–3669. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0251-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarantino U, Cannata G, Lecce D, et al. Incidence of fragility fractures. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parfitt AM, Mathews CH, Villanueva AR, et al. Relationships between surface, volume, and thickness of iliac trabecular bone in aging and in osteoporosis. Implications for the microanatomic and cellular mechanisms of bone loss. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1396–1409. doi: 10.1172/JCI111096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duboeuf F, Hans D, Schott AM, et al. Different morphometric and densitometric parameters predict cervical and trochanteric hip fracture: the EPIDOS Study. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1895–1902. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.11.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeBlanc ES, Hillier TA, Pedula KL, et al. Hip fracture and increased short-term but not long-term mortality in healthy older women. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1831–1837. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marks R, Allegrante JP, Ronald MacKenzie C, Lane JM. Hip fractures among the elderly: causes, consequences and control. Ageing Res Rev. 2003;2:57–93. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Rekeneire N, Visser M, Peila R, et al. Is a fall just a fall: correlates of falling in healthy older persons. The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:841–846. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graafmans WC, Ooms ME, Hofstee HM, et al. Falls in the elderly: a prospective study of risk factors and risk profiles. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:1129–1136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wainwright SA, Marshall LM, Ensrud KE, et al. Hip fracture in women without osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2787–2793. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talbot LA, Musiol RJ, Witham EK, et al. Falls in young, middle-aged and older community dwelling adults: perceived cause, environmental factors and injury. BMC Pub Health. 2005;5:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.González López-Valcárcel B, Sosa Henríquez M. Estimate of the 10-year risk of osteoporotic fractures in the Spanish population. Med Clin(Barc) 2013;140:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. . WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. World Health Organization (online). Available at http://www.who.int/ageing/projects/ falls_prevention_older_age/en. 2007.

- 26.Dy CJ, McCollister KE, Lubarsky DA, Lane JM. An economic evaluation of a systems-based strategy to expedite surgical treatment of hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;14:1326–1334. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfson L, Whipple R, Derby CA, et al. Gender differences in the balance of healthy elderly as demonstrated by dynamic posturography. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M160–M167. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Englund U, Nordström P, Nilsson J et al. Physical activity in middle-aged women and hip fracture risk: the UFO study. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:499–505. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hornbrook MC, Stevens VJ, Wingfield DJ, et al. Preventing falls among community-dwelling older persons: Results from a randomized trial. Gerontologist. 1994;34:16–22. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koutserimpas C, Agouridakis P, Velimezis G, et al. The burden on public emergency departments during the economic crisis years in Greece: a two-center comparative study. Public Health. 2019;167:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]