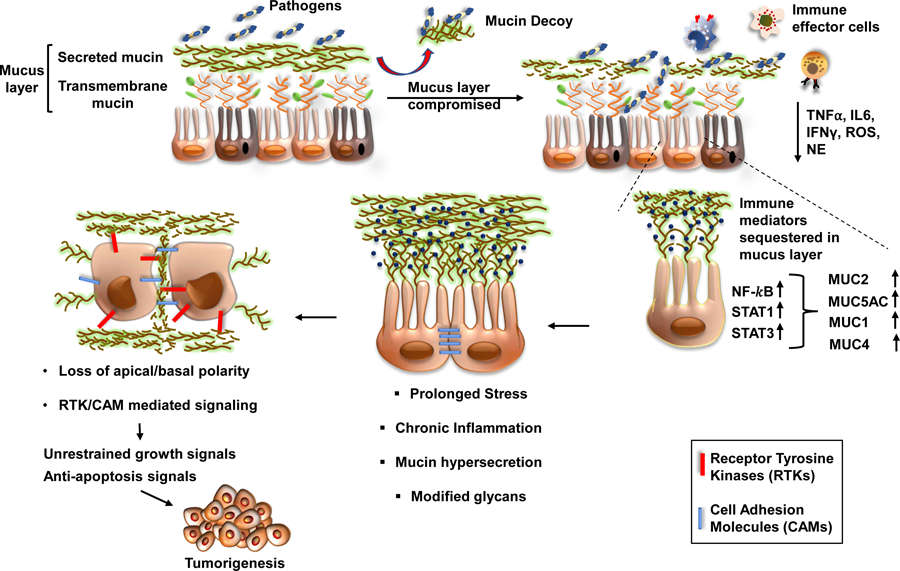

Figure 1: Mucins at the crossroads of mucosal protection, inflammation and tumorigenesis.

The protective mucus layer on the epithelial lining is comprised of transmembrane and secreted mucins. The invading pathogens can compromise the secreted mucus layer and gain access to the transmembrane mucins, which are apically arranged close to the epithelial surface. Upon binding of the pathogens, mucins shed their extracellular domains as decoy receptors, thereby facilitating pathogen clearance. Subsequently, the cytoplasmic domain of the mucins like MUC1 and MUC16 can transduce intracellular signals in response to local inflammatory milieu containing TNFα, IL6, IFNγ, ROS, and RNS. The localized enrichment of immune mediators leads to an activation of transcription factors such as NF-κβ, STAT1, and STAT3, which upregulate the expression of mucins. In response to infection and subsequent inflammation, the mucin-producing goblet cells become hyperplastic (commonly called goblet cell hyperplasia) and secrete mucins with altered glycans to obscure pathogenic adhesion and prevent mucus degradation. Chronic inflammation and stress, however, cause the underlying epithelial cells to lose their polarity and activate signaling pathways for repair, cellular differentiation, and survival. Due to loss of apical-basal polarity, mucins can interact with various receptor tyrosine kinases and cell-adhesion molecules to mediate sustained growth signals, thereby facilitating the events of tumorigenesis.