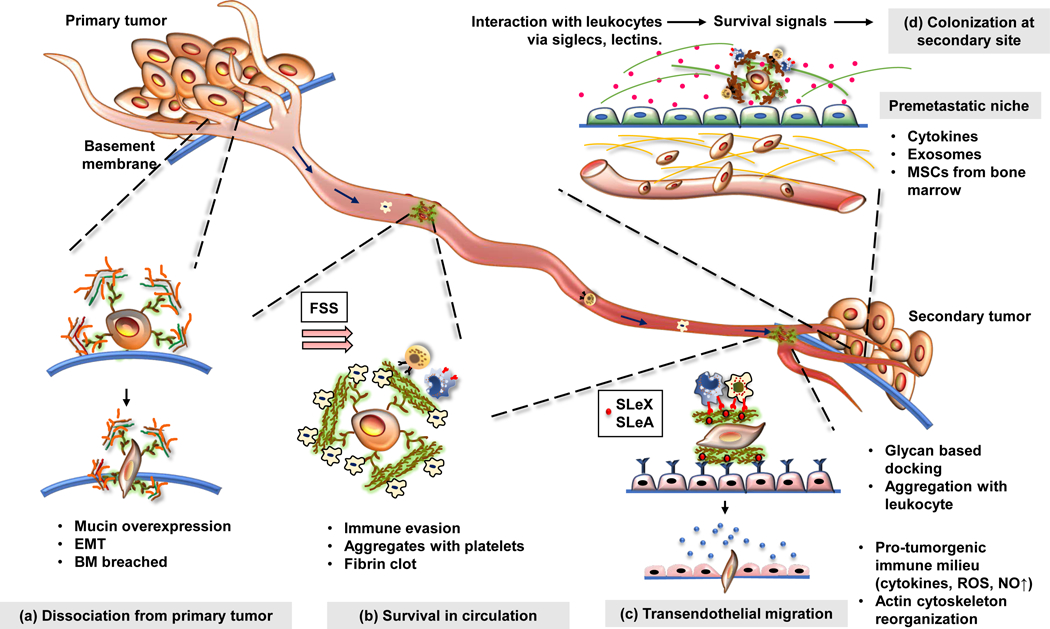

Figure 2: Mucins provide dynamic shield to the tumor cells during their metastatic journey.

Mucin overexpression is associated with most malignancies. (a) At the primary tumor, secreted and transmembrane mucins facilitate epithelial to mesenchymal transition of the cancer cells through a plethora of signaling pathways and steric hindrance of cell-cell interactions. Furthermore, cancer cells utilize multiple cell-autonomous and paracrine mechanisms to breach the basement membrane. Mucins facilitate the synthesis of matrix-degrading proteases, maintain a pro-tumorigenic immune milieu, and establish interaction between cancer cells and the basement membrane via their extracellular domains which resemble matrix proteins. (b) Once the cancer cells exit the primary tumor, they face the fluid shear stress (FSS) and, circulatory immune cells in the bloodstream. Mucin glycans bear ligands that can bind to selectins on platelets and subsequently form a cancer cell-platelet-fibrin aggregate that protects cancer cells from the mechanical stress in circulation. Meanwhile, heavily glycosylated extracellular domains of mucins can mask tumor-associated antigens on the cancer cells, helping them evade immune surveillance. (c) While circulating through the bloodstream, the cancer cells dock on the endothelium lining (through selectins), undergo rolling, and subsequently extravasate to reach the secondary organ. Mucins help the cancer cells to attach to the endothelium via sialylated ligands for selectins (SLeX, SLeA) and help them extravasate using various adhesion molecules (integrins, ICAMs). (d) At the secondary site, mucins may facilitate the formation of a pre-metastatic niche and provide survival signals to the cancer cells. Together, these steps culminate in the establishment of a successful metastatic lesion.