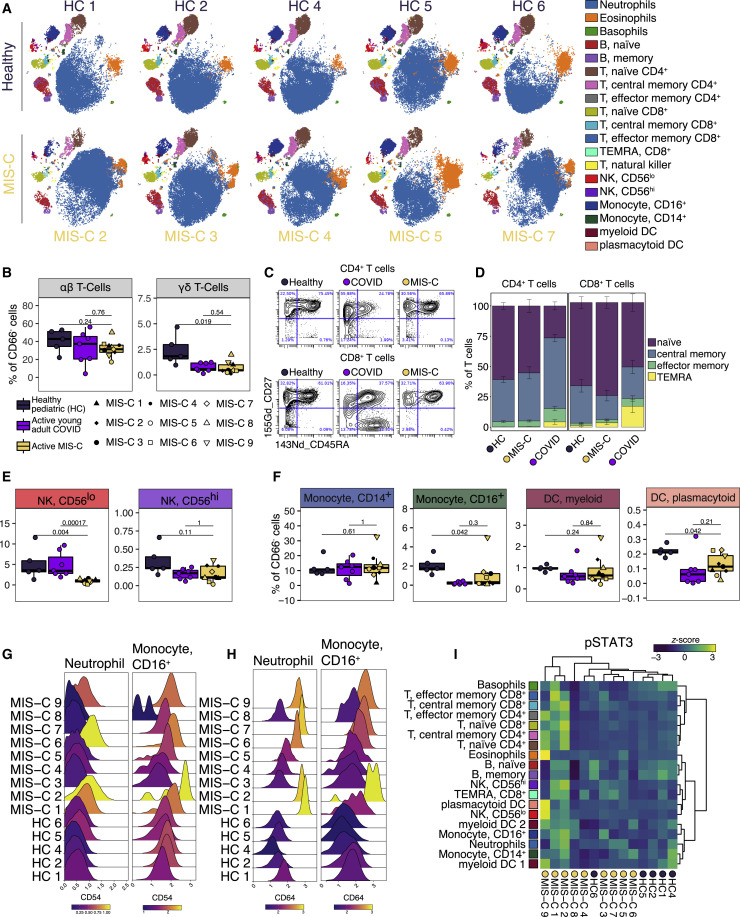

Figure 3.

Immunophenotyping of MIS-C Patient Peripheral Blood by Mass Cytometry

(A) Representative t-SNE plots illustrating the immune cell distribution in whole blood from age-matched healthy controls (N=5) and MIS-C patients (5 shown; N=9 total).

(B) T cell subset frequencies expressed as percent of CD66- cells (non-granulocytes) from age-matched healthy controls (N=5), acute COVID-19 infection in young adults (N=7), and MIS-C patients (N=9).

(C) Representative scatterplots for naïve, central memory, effector memory, and T effector memory re-expressing CD45RA (TEMRA) cells in a representative healthy donor, MIS-C patient, and an acute young adult COVID-19 patient.

(D) Quantification of T cell subsets across samples.

(E) NK cell subsets quantified as percent of CD66− cells.

(F) Monocyte and dendritic cell sub-population frequencies quantified as percent of CD66− cells.

(G and H) CD54 (G) and CD64 (H) expression in neutrophil and CD16+ monocyte subsets, color-coded by the mean log10 transformed signal intensity.

(I) STAT3 phosphorylation across immune cell subtypes for all MIS-C patients and healthy controls. Heatmap is colored as Z scored scaled expression. Unsupervised clustering of patient samples and cell types was done using the Ward’s method (distance metric: canberra). All boxplots represent the median and interquartile range with error bars spanning 1.5× interquartile range. Statistical significance between healthy pediatrics and active MIS-C or active MIS-C and acute young adult COVID-19 were assessed with the Wilcoxon ranked sum test and corrected for multiple testing (Benjamini-Hochberg method).

See also Figure S4.