Abstract

Fe(II)- and α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases have emerged as important catalysts for the preparation of non-natural amino acids. The stoichiometric supply of the cosubstrate α-ketoglutarate (αKG) is an important cost factor. A combination of the N-succinyl amino acid hydroxylase SadA with an l-glutamate oxidase (LGOX) allowed for coupling in situ production of αKG to stereoselective αKG-dependent dioxygenases in a one-pot/two-step cascade reaction. Both enzymes were used as immobilized enzymes and tested in a preparative scale setup under process-near conditions. Oxygen supply, enzyme, and substrate loading of the oxidation of glutamate were investigated under controlled reaction conditions on a small scale before upscaling to a 1 L stirred tank reactor. LGOX was applied with a substrate concentration of 73.6 g/L (339 mM) and reached a space-time yield of 14.2 g/L/h. Additionally, the enzyme was recycled up to 3 times. The hydroxylase SadA reached a space-time yield of 1.2 g/L/h at a product concentration of 9.3 g/L (40 mM). For both cascade reactions, the supply with oxygen was identified as a critical parameter. The results underline the robustness and suitability of α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases for application outside of living cells.

Keywords: l-Glutamate oxidase, N-Succinyl amino acid hydroxylase, Cell-free system, Immobilized enzymes, Non-natural amino acids, In situ production, Sustainability, Recycling, Biocatalysis, Cascade reactions

Short abstract

An efficient cell-free system for the production of a redox cosubstrate using a recyclable enzyme with a product formation rate of up to 14.16 g/L/h facilitates industrial usage of αKG-dependent dioxygenases.

Introduction

Enzymatic oxyfunctionalization of C–H bonds has a high potential for the industrial production of chiral building blocks.1 While focus has been so far mainly on cellular systems,2 technological advances for the supply of oxygen and regeneration of cofactors have paved the way for in vitro applications. Within the enzyme superfamily of α-ketoglutarate (αKG) and iron(II) dependent dioxygenases, many enzymes are reported to perform a variety of oxidative reactions, with the majority of them being hydroxylation reactions.3 Furthermore, αKG/Fe(II) dependent dioxygenase reactions include desaturation,4 ring formation,4 ring expansion,5 halogenation,6 and endoperoxidation.7 In contrast to the oxidative P450 enzymes, these oxygenases contain no heme complex for the coordination of the ligand in the active site, and here, the iron(II) is bound by two histidine residues and an aspartate or glutamate residue. Most of the αKG/Fe(II) dioxygenases present a conserved His-X-Asp/Glu-Xn-His motif, and the ligands are bound in an octahedral complex. The cofactor αKG coordinates with its C2 keto oxygen and C1 carboxylate to the Fe(II) and is decarboxylated irreversibly during the reaction. The proposed mechanism involves a Fe(IV)=O species as initiator for the hydroxylation, starting with the abstraction of a hydrogen atom from the substrate to form Fe(III)–OH. A radical is formed in the substrate, which is attacked by the OH to complete the hydroxylation and leave the Fe(II) in its initial state.8

During the last years, several amino acid hydroxylases from this superfamily were identified and further investigated as hydroxylated amino acids are of high interest for the pharmaceutical industry. One example is the hydroxylation of l-arginine by the l-arginine oxygenase (VioC) from Streptomyces vinaceus, which is an intermediate in the production of tuberactinomycin family antibiotics like viomycin.9,10 Another example is the l-isoleucine dioxygenase (IDO) from Bacillus thuringiensis, producing (2S,3R,4S)-4-hydroxy-l-isoleucine (HIL) with antidiabetes and antiobesity activity.2,11

Several challenges can arise in the application of these enzymes in industry such as the determination or the propriate oxygen supply to achieve high enzyme activity and coping with the low stability of the dioxygenase under oxidative conditions. Moreover, the redox cosubstrate αKG is consumed irreversibly during the reaction and must be constantly supplied. αKG as part of the central metabolism can be produced in vivo by using bacterial strains with deletions in the tricarboxylic acid cycle.2 We envisioned that the enzymatic oxidation of inexpensive l-glutamate would be an elegant way to supply the cosubstrate in cell-free systems. Furthermore, cell-free systems can enhance the sustainability and present several advantages over the corresponding whole cell process namely the following: the absence of undesired metabolites from the cellular background that can lower the isolated yields and the absence of substrate toxicity on the cells and limited mass transfer. Additionally, a cell-free system allows more degrees of freedom in the process optimization.12 Enzyme immobilization can further increase the sustainability as the catalyst can be easily separated and reused while improving the downstream processing resulting in higher product purity and a lower amount of waste generated.

Dehydrogenases, deaminases, and oxidases, among other enzymes, can produce αKG, and the l-glutamate oxidase (LGOX) from Streptomyces ghanaensis, identified in 2014 by Nui and co-workers, appeared to be a promising candidate for αKG production.13 Fan and co-workers achieved a space-time yield of 5.3 g/L/h in the production of αKG from l-glutamate in batch fermentations using E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring LGOX.14

β-Hydroxy-l-valine is a chiral building block for several antibiotic and antiviral compounds like resormycin, tigemonam, HIV protease inhibitors, or antiviral agents for the treatment of hepatitis C.15−18 The first synthesis of this hydroxy amino acid was reported by Abderhalden in 1934, and by now several ways to produce the chiral α-hydroxy-l-valine are reported.19 A chemical synthesis was described by Belokon and co-workers using a condensation of acetone with glycine catalyzed by a Ni(II) complex, which yielded the d-product.20 Enzymatic synthesis from the corresponding keto acid by a leucine dehydrogenase is reported to yield 82% of the desired β-hydroxy-l-valine18 but requires the production of the precursor substrate α-keto-β-hydroxyisovalerate. The N-substituted l-amino acid dioxygenase SadA from Burkholderia ambifaria has been shown to hydroxylate several branched-chain amino acids in the β-position.21 The stability of the enzyme is comparatively high, and, not surprisingly, SadA was the first branched-chain dioxygenase that was successfully crystallized. Therefore, we envisioned a simple synthesis by SadA-catalyzed regioselective hydroxylation of N-succinyl-l-valine. To facilitate the supply of the redox cosubstrate αKG, we coupled enzymatic oxidation of l-glutamate to the hydroxylation reaction using a cascade approach (see Scheme 1).

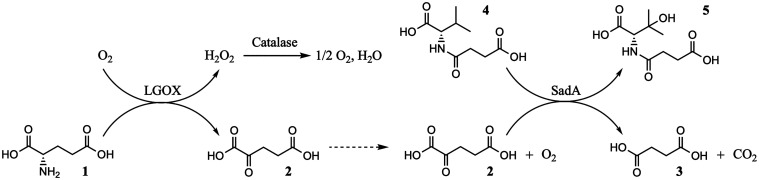

Scheme 1. Enzymatic Cascade Reaction of LGOX and SadA Showing the Transformation of l-Glutamic Acid (1) to αKG (2) and Subsequent Decarboxylation to Succinic Acid (3) to Initiate the Hydroxylation of N-Succinyl-l-valine (4) to N-Succinyl-β-hydroxy-l-valine.

Immobilization appeared as a suitable strategy to increase the enzymatic stability under process-near conditions. Moreover, this setup would enable the easy removal of the catalyst from the reaction system and recycling of both enzymes to increase the catalysts’ productivities. In addition, full control over the oxygen level and supply was required to ensure a safe operation of the process on a preparative scale.

Experimental Section

Enzyme Preparation

The genes for SadA (Accession # WP_011660927) and LGOX (Accession # EFE71695.1) were ordered as synthetic genes (GeneArt) and cloned via Gibson Assembly into a pET28a(+) expression vector (for primer sequences see the Supporting Information), whereas the synthetic gene for Pseudomonas syringae catalase (Accession # WP_080267435.1) was ordered directly from ATUM in the corresponding l-rhamnose inducible expression vector.22 For expression from pET28a(+), E. coli BL21 (DE3) was used as the expression strain. Cells were grown in TB medium to OD600 0.5 and induced by addition of 1 mM and 0.4 mM IPTG for SadA and LGOX, respectively. The catalase was expressed in an E. coli RV308 Δrha strain cultivated in TB medium, and induction was performed at OD600 0.5 with 0.02% (w/v) l-rhamnose. After overnight incubation at 28 °C, cells were harvested and stored at −20 °C until further use.

Cell pellets were resuspended in a 2:1 ratio in potassium phosphate (KPI) buffer (50 mM; pH 6.5) and disrupted by sonication. SadA and LGOX were further processed before application either by purification with HisPur Ni-NTA affinity chromatography or directly immobilized on EziG Amber according to the suppliers protocols. The catalase was usually applied as a cell-free extract (CFE), and only in specific experiments was it used as an immobilized enzyme on EziG Amber.

Immobilization on EziG

All enzyme immobilizations were performed by mixing the CFE extract containing the corresponding enzyme with the EziG carriers in a rotary shaker for 2 h at 4 °C. Per millilliter of the CFE extract 50 mg of EziG Amber was used. After the incubation, the carriers were washed three times with 1 mL of potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.5) per 50 mg of EziG. Afterward the immobilized enzyme was directly used in the optimization reactions. For the testing of the multienzyme reaction in one-pot and two steps, a purified enzyme was immobilized, and the immobilization conditions are mentioned in the corresponding paragraph.

Multienzyme Reaction in One-Pot-One-Step

Both reactions were performed simultaneously in a 10 mL stirred tank reactor at 30 °C and 1200 rpm stirring rate. Reaction components N-succinyl-l-valine (10 mM), l-glutamic acid (15 mM), ascorbic acid (10 mM), DTT (1 mM), and FeSO4 (0.5 mM) were mixed in potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.5). The reaction was started by addition of the purified enzymes (0.5 mg/mL SadA, 0.1 mg/mL LGOX, 1% (v/v) catalase CFE).

Multienzyme Reaction in One-Pot-Two-Steps

First, the module 1 reaction was performed in a 10 mL stirred tank reactor at 30 °C and 1200 rpm stirring rate. l-Glutamic acid (50 mM) was mixed with 1% (v/v) catalase CFE in KPI buffer (50 mM, pH 6.5), and the reaction was started upon addition of 0.6 mg of LGOX on 5 mg of EziG Amber. After 4 h the immobilized enzyme was filtered off, and the reaction filtrate was diluted to a final concentration of 15 mM αKG before starting module 2. Additionally, other reaction components (10 mM N-succinyl-l-valine, 10 mM ascorbic acid, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM FeSO4) were mixed into the reactor, and the reaction was started by addition of 10 mg of SadA on 90 mg of EziG Amber.

Optimization of the α-Ketoglutarate Generation Module

Standard reaction conditions for all optimization reactions were as follows: 30 mL scale in stirred tank reactors, 1200 rpm stirring rate, and 30 °C temperature. If not mentioned otherwise, reactions were performed with l-glutamate (100 mM) and 1% (v/v) catalase CFE with an aeration rate of 10 mL/min. By addition of 4.17 g/L LGOX EziG the reaction was started. For the optimization of the substrate loading, 8.33 g/L LGOX EziG was used. All reactions were done in duplicate; more replicates were done only in the case of high variability (>3%).

Optimization of the Hydroxylation Module

The standard reaction conditions were the same as for LGOX module optimization. If not mentioned otherwise, reactions were performed with N-succinyl-l-valine (10 mM), αKG (15 mM), ascorbic acid (10 mM), DTT (1 mM), and FeSO4 (0.5 mM) with an aeration rate of 10 mL/min air. Reactions were started by addition of 8.33 g/L SadA EziG. In substrate loading optimization experiments, 41.67 g/L SadA EziG was used for all substrate concentrations. All reactions were done in duplicate; more replicates were done only in the case of high variability. For the recyclability test of the immobilized enzyme, the carriers were filtered from the reaction suspension and reused in a subsequent reaction under standard conditions.

Scale-up of the α-Ketoglutarate Generation Module

The large scale reaction was performed in a 1 L stirred tank reactor at 30 °C with a stirring rate of 300–400 rpm. l-Glutamic acid (500 mM, 73.5 g) was dissolved in KPI-buffer (50 mM), and the pH was set to 6.5. The substrate solution was saturated with pure oxygen by bubbling O2 at a flow rate of 30 mL/min. After addition of 10% (v/v) catalase CFE, 4.17 g/L LGOX EziG was added to start the reaction. O2 levels were measured within the reaction suspension and in the outlet of the reactor to calculate the oxygen mass balance. After full conversion of the substrate, the enzyme was removed by filtration and reused in another reaction under similar reaction conditions.

Results and Discussion

Establishment of the Process with Two Separated Modules

The envisioned one-pot/two-step process consisted of an α-ketoglutarate generation module (1) followed by a hydroxylation module (2). Initially, two different alternative reactions were considered for the generation of the cosubstrate α-ketoglutarate from l-glutamate. One option is a combination of glutamate dehydrogenase (GluDH) from Bacillus subtilis, which requires addition of an NADH oxidase. Here, the water-producing NADH oxidase (NOX) from Streptococcus mutans for regeneration of the oxidized form of the nicotinamide cofactor would avoid undesired formation of hydrogen peroxide. The second system uses l-glutamate oxidase (LGOX) producing αKG with H2O2 as a side product. Catalase needs to be added to remove hydrogen peroxide, as it has an influence on the enzyme activity as well as on the product stability. For module 2 the hydroxylation of N-succinyl-l-valine catalyzed by the N-succinyl amino acid hydroxylase SadA was chosen. SadA was found to produce a mix of products with a yield of 65% for the desired β-hydroxylation product according to NMR analysis.23 This cascade was chosen to demonstrate the potential for the coupling of an αKG generation reaction with a subsequent hydroxylation using an αKG- and Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase.

The GluDH/NOX system for module 1 requires NADH as an additional cofactor, which is an important cost factor even in catalytic amounts. Additionally, Ödman and co-workers demonstrate that product inhibition would be the most limiting factor of the system for an industrial application. Therefore, using LGOX appeared to be more promising for the production of αKG, as it is not reported to be affected by product inhibition.24 Using LGOX, however, requires removal of its coproduct H2O2 as this is expected to affect the stability of the enzyme. Moreover, the stability of αKG against reactive oxygen species (ROS) is low, and any ROS might result in the undesired decarboxylation to succinic acid.25 Different catalases were considered for module 1 as these enzymes are the most straightforward option to remove H2O2. Taking into account that the hydroxylated product might be used for the pharmaceutical or nutrition industry, an enzyme isolated from bovine (as some commercial preparations are) or other animal derived material is ineligible due to possible contamination risks.26 Therefore, several recombinantly expressed catalases were tested (data not shown). The best candidate among the catalases for the reaction system screened based on activity and the KM value was a microbial catalase from Pseudomonas syringae. Recombinant production in E. coli yielded a cell-free extract with a volumetric activity of ∼250.000 U/mL.

With the two modules to be combined in a cascade reaction, the question was whether both reactions could be performed simultaneously in a one-pot/one-step reaction. A sequential reaction mode would allow isolation of both immobilized biocatalysts in pure form, separately. Mixing both immobilized enzymes would be detrimental in view of efficient recycling, as the differently formulated enzymes vary in their stability. This would result in an inefficient recycling especially in later cycles; therefore, a sequential mode was preferred.

Reactions at an analytical scale (10 mL) showed that the one-pot/one-step setup did not influence LGOX activity as no differences were observed compared to single LGOX reactions. The inhibition of the amino acid hydroxylase by the reaction components of the first step was attributed to the formation of hydrogen peroxide and other reactive oxygen species. Therefore, a setup was designed with both reactions separated temporally in a sequential reaction cascade. LGOX performed as already described before and reached full conversion after 4 h. After removal of the first reaction catalyst, the hydroxylation using SadA was started by adding reaction components for module 2. We were pleased to find that both reactions proceeded to full conversion (Figure 1). The one-pot/two-step setup seems to be a suitable reaction concept for this cascade reaction. Furthermore, the temporal separation would make a combination of module 1 with different dioxygenases in the hydroxylation module easier, as reaction requirements of both enzymes can be significantly different and, by the separation, both can work under their optimal conditions. Adding SadA together with LGOX resulted in complete activity loss of the former. Even though a catalase was applied to remove the generated H2O2, some amount will still be present as the KM values of most catalases are high (60 mM and higher). Complete conversion of the l-glutamate to αKG and complete removal of hydrogen peroxide in a sequential mode completely restored SadA activity.

Figure 1.

Reaction time course of a sequential one-pot/two-step reaction at a 10 mL scale with module 1 (0–240 min) and module 2 (240–480 min). In the first module, l-glutamate (15 mM, ⧫) is consumed, and α-ketoglutarate is produced (■) followed by the second module consuming α-ketoglutarate (■) and N-succinyl-l-valine (10 mM, ●) to produce N-succinyl-l-hydroxyvaline (▲)*.

For the further development of the cascade process, the enzymes were used in immobilized form for easy separation and recycling to increase the productivity. Additionally, removal of the immobilized enzyme would simplify the workup, as soluble enzymes complicate the downstream processing in most cases.

Optimization of the α-Ketoglutarate Generation Module

Each reaction module was further investigated at a 30 mL scale in a stirred tank reactor. Tuning the oxygen supply in the reactor setup was a critical factor for the optimization, as both modules consume significant amounts of oxygen. Several reaction parameters were tested in the optimization of the αKG generation module. At first, oxygen consumption was examined by comparing the reaction without any supply of oxygen and addition of 10 mL/min synthetic air. As no further dispersion was applied at this scale, we were aware that gas distribution was not optimal in this reactor. Yet, we expected that this issue could be more easily addressed at a 500 mL scale. The air was applied through a thin tube, and relatively large bubbles were released in the reactor. Therefore, the stirring rate was a more important parameter to tune the residence time of the gas bubbles in the reaction solution and to increase the gas/liquid surface.

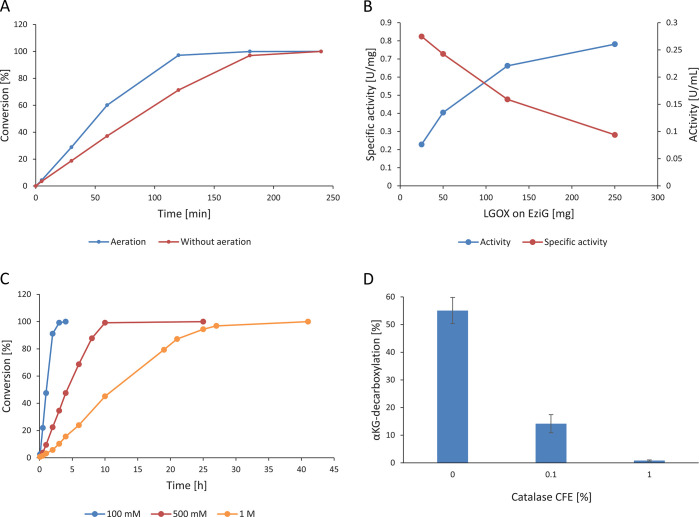

Supplying the reaction with additional oxygen increased the reaction rate by 66%, and full conversion was reached earlier (Figure 2A). To further get an impression about oxygen limitation and find an optimal enzyme loading, the amount of immobilized enzyme used in the reaction was varied. The best compromise between overall activity and specific activity appeared to be around 4.17 g/L, as the specific LGOX- EziG activity decreased at higher catalyst loadings (Figure 2B). At higher enzyme amounts, the activity was limited by the maximal oxygen transfer rate of this reactor setup resulting in a lower specific activity. LGOX-EziG (4.17 g/L) appeared to be the best enzyme loading, as it was balanced between total activity applied and specific activity observed in the reactor: lower amounts of enzyme would not incur in oxygen limitation but would lead to longer batch times, especially with high substrate concentrations.

Figure 2.

Key reaction parameters for the LGOX-catalyzed conversion of l-glutamate to αKG at a 30 mL scale. [A] Influence of aeration of 10 mL/min. [B] Specific activity and volumetric activity for different LGOX-EziG amounts used (100 mM l-glutamate, 50 mg of EziG/mL CFE). [C] Influence of the concentration of l-glutamate (250 mg of LGOX-EziG). [D] Decarboxylation of αKG to succinate after a 4 h reaction at different volumes of catalase CFE added to the reaction (100 mM l-glutamate, 125 mg of LGOX-EziG).

Different concentrations of l-glutamate (100 mM to 1 M) were tested to determine if potential substrate and product inhibition might affect the overall efficiency of the process. Substrate concentrations up to 500 mM showed no significant difference in the initial rate compared to reactions with 100 mM substrate (0.78 ± 0.09 U/mL), whereas a substrate concentration of 1 M resulted in a reaction rate of only 54% (0.42 ± 0.03 U/mL) compared to 100 mM substrate (Figure 2, C). No significant decrease of the reaction rate was observed over time, indicating that the formed product αKG did not inhibit LGOX significantly.

Lastly, the catalase loading was optimized to ensure proper hydrogen peroxide removal. Furthermore, coimmobilization of the catalase and LGOX was considered to reuse both enzymes and further improve the efficiency of the process. Therefore, the catalase was immobilized in two different setups on the carrier. On the one hand, it was premixed with LGOX and then immobilized on the corresponding carrier amount, and on the other hand, the catalase and LGOX were immobilized separately and only mixed in the reactor. Afterward, the immobilized catalase formulations were compared with free enzymes applied as cell-free extract. One percent (v/v) of the catalase applied as CFE was necessary to remove H2O2 and avoid decarboxylation of αKG; in contrast, in both setups immobilized catalase decarboxylation could not be prevented using an amount equivalent to 3% (v/v) of cell-free extract with catalase. At the highest catalase loading in both setups (co- and separately immobilized) a decarboxylation ratio of 19% was still observed with a product yield of 81%. This may be due to a lower catalase activity in the immobilized form compared to the free catalase. In addition, separation of the immobilized enzymes or combined application did not make any difference from a practical point of view. A loading of 4.17 g/L LGOX-EziG, a substrate concentration of 500 mM l-glutamate, and 1% (v/v) of free catalase CFE with aeration for higher reaction rates were the optimal conditions determined and were the starting point of the upscaling.

Optimization of the Hydroxylation Module

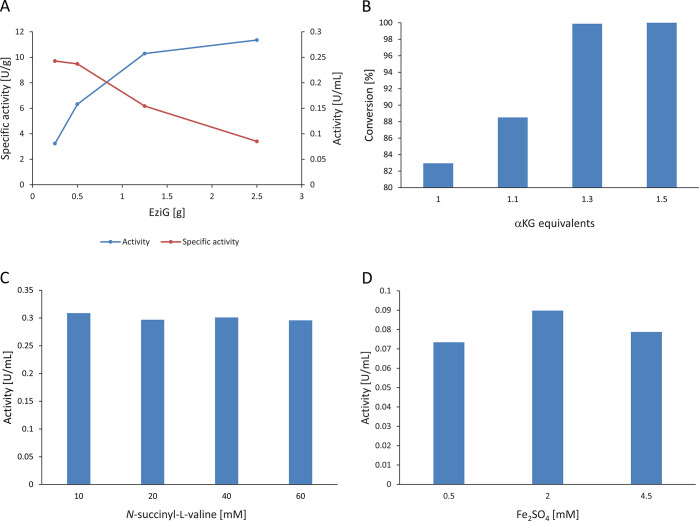

Similar parameters were screened in the optimization of the hydroxylation module. In contrast to LGOX, SadA showed no difference in the reaction rate at low enzyme loadings in the presence or absence of aeration. The dioxygenase has a much lower specific activity toward N-succinyl-l-valine (0.08 U/mg; comparable to results by Hibi and co-workers)23 in comparison with LGOX on l-glutamate, and the overall oxygen consumption is too low to reach limiting oxygen transfer rates at low enzyme loadings. Increasing the enzyme loading above 16.67 g/L EziG showed that SadA reached as well oxygen mass transfer limitations as seen for LGOX. An amount of 41.67 g/L SadA-EziG was found to be the best compromise between activity and oxygen supply requirements. Similar to the first module, the reaction rate seemed to approach a plateau with higher enzyme loadings. SadA maximimum activity was below 0.33 U/mL, whereas for LGOX it was above 0.67 U/mL. This difference can be explained by the fact that LGOX uses both oxygen atoms of O2 for the oxidation of its substrate, while SadA uses only one oxygen atom for the hydroxylation and the other ends up in the αKG conversion to succinate. In addition, in the first module H2O2 is at least partly recycled to O2 and H2O.

Before investigating the optimal substrate loading, different concentrations of the cofactor α-ketoglutarate (1–1.5 equiv) were tested in order to find the optimal concentration and ratio. One equivalent only yielded a conversion of 83%, whereas increasing αKG to 1.3 equiv resulted in 99% conversion. Further increasing αKG to 1.5 equiv finally showed full conversion. Due to low activity of the SadA enzyme, concentrations up to 60 mM were tested, and no substrate inhibition was observed. However, full conversion was only achieved for substrate loadings up to 40 mM (9.3 g/L). For higher substrate loadings, the reaction reached a plateau and did not proceed any further. The initial activity did not differ significantly between 10 mM and 60 mM (Figure 3C). The fact that the reaction at 60 mM 5 stopped after 8 h at 82% conversion and that addition of freshly prepared enzyme (not shown) did not lead to further conversion indicates product inhibition.

Figure 3.

Key reaction parameters for the SadA-catalyzed conversion of N-succinyl-l-valine to the corresponding hydroxy compound at a 30 mL scale. [A] Specific activity and volumetric reaction activity for different SadA-EziG amounts used (50 mg of EziG/mL CFE; units per gram EziG, 10 mM N-succinyl-l-valine). [B] Conversion for different equivalents of αKG applied after 4 h (10 mM N-succinyl-l-valine). [C] SadA volumetric reaction activity at conversion rates <50% for different substrate concentrations applied (1.25 g of SadA-EziG). [D] Volumetric reaction activities for SadA at different FeSO4 concentrations during the reaction (5 mM N-succinyl-l-valine, 250 mg of SadA-EziG).

Additionally, the iron concentration was investigated. It is well-known that Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenases of the jellyroll type do not tightly coordinate the iron atom. A beneficial effect of the addition of FeSO4 to SadA was already reported previously by Hibi and co-workers.27 Different FeSO4 concentrations showed no significant influence on the reaction rate, thus, the reaction was performed with 0.5 mM as the literature reference value. While full conversion was achieved, recycling of the enzyme was less successful. After the first reaction cycle, the hydroxylase showed only 10% of the initial reaction rate (data not shown). Nevertheless, the formulation with EziG allows concentrating the enzyme to provide the high amounts needed for the conversion of 50 mM substrate. Due to the low specific activity of 0.08 U/mg, a large amount of enzyme is necessary, and the application as a cell-free extract would hinder the separation of the product. The main advantage of the EziG immobilization lies in the simplification of the workup and not in an increase of the total turnover number. The quantitative conversion of 40 mM substrate in 5 h and a space-time yield of 1.21 g/L/h are a very promising starting point. While EziG allowed quick immobilization, a different carrier may result in higher operational stability and reduced enzyme leaking.

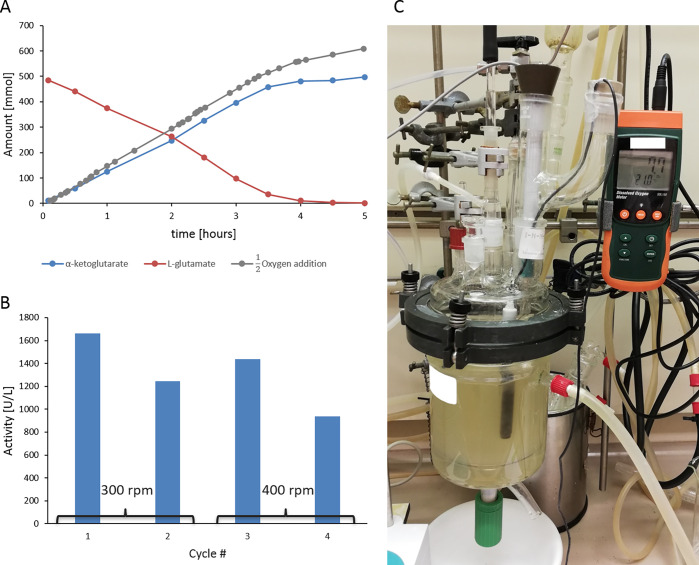

Scale-up of the α-Ketoglutarate Generation Module

To investigate the role of oxygen supply under conditions close to the process conditions, we performed the enzymatic oxidation of l-glutamate in a 1 L stirred tank batch reactor (Figure 4). This reactor is an exact downscale of a 200 L pilot plant reactor and allows the study of oxygen-dependent reactions under process-near conditions. In contrast to the small scale reactors, here synthetic air or pure oxygen can be supplied to the reaction using a sintered frit for optimal gas dispersion. The reaction was performed with 4.17 g/L LGOX-EziG and a substrate loading of 500 mM (73.57 g/L). Increasing the catalase concentration to 10% (v/v) resulted in a higher total reaction rate (3.3-fold) in this setup compared to the 30 mL scale, which was in agreement with first reaction tests (data not shown). The usage of pure oxygen might expose the enzymes to a higher oxidative stress level, and further increasing the catalase loading proved to be beneficial. Supplying pure oxygen with rates between 20 and 40 mL/min resulted in full l-glutamate conversion within 5 h with an αKG yield of 96% and a space-time yield of 14.16 g/L/h. By comparing the oxygen input and output in the reaction system, it was possible to determine that 1.3 equiv of oxygen was consumed to oxidize 1 equiv of l-glutamate to αKG.

Figure 4.

[A] Reaction progress of a 1 L reaction showing l-glutamate (500 mM) consumption and αKG production in relation to the oxygen amount added. [B] Total activity for LGOX under recycling conditions with 300 and 400 rpm stirring rates, respectively. [C] Setup of the reactor with pH and O2 electrode and O2 and N2 inlet and gas outlet.

After one successful reaction cycle with immobilized LGOX, ideally the enzyme would be recycled several times to increase the efficiency of the enzyme use in the overall process. The reaction was performed again at the same oxygen supply rate (30 mL/min) and with a similar stirring rate (300 rpm). The reaction rate decreased to 75% compared to the first reaction cycle, and full conversion was reached with a yield of 95%. Increasing the stirring rate (400 rpm) in the third cycle partially restored the reaction rate up to 86% compared to the first cycle, and a similar yield was obtained. In cycle 4 however, the reaction rate further decreased to 56% of the first cycle. Due to the lower reaction rate only a 70% yield was achieved after 10 h. Nevertheless there was still significant activity observed in the fourth cycle, and a total of 260.24 g of product could be produced with one batch of immobilized LGOX.

Conclusions

Overall, a robust modular reaction cascade was set up in a one-pot/two-step approach combining α-ketoglutarate production from l-glutamate using LGOX and using the αKG produced in this module with minimal downstream processing (filtering off the immobilized LGOX) for the hydroxylation of N-succinyl-l-amino acids. Both enzymes were applied in an immobilized form for possible recycling. SadA hydroxylase was found to have a limited operational stability preventing its recycling. Nevertheless, both enzymes showed good immobilization yields and activities in an immobilized form leading to the conclusion that the immobilization itself is a valuable option for an industrial application. The two modules showed excellent to good space-time yields of 14.2 g/L/h and 1.2 g/L/h, respectively. The LGOX/catalase module is a generic tool for αKG production from l-glutamate in vitro and can be combined with other αKG requiring enzyme reactions and modules or used for αKG production itself.

The overall process shows a moderate atom economy of 54%. This is typical for redox reactions employing organic cosubstrates. As the decarboxylation of αKG forms succinate, any reaction employing an αKG-dependent dioxygenase will have a similar atom efficiency. Unfortunately, no economically viable reaction for the regeneration of αKG from succinate has been developed yet. While our approach does not improve the atom efficiency of the dioxygenase reaction, it can be argued that the bulk chemical l-glutamate is produced in an extremely efficient fermentative process and that a substitution of αKG by l-Glu as cosubstrate for hydroxylations contributes to an increase of the sustainability of this class of redox reactions. To further improve the process, enzyme engineering could improve both stability and activity, especially of SadA, to allow recycling and to increase the space-time yield. With its much higher stability, LGOX could be recycled up to four times with minimal loss of activity on a 1 L scale. Using a catalase with a lower KM value would further improve the α-ketoglutarate production and would significantly decrease the amount of catalase required.

Regarding the process conditions, an optimal oxygen supply appeared to be a critical factor for both enzymes. For LGOX, a better oxygen supply on a 1 L scale could increase the reaction rate significantly. Lastly the N-succinyl-β-hydroxy-l-valine has to be processed to release the desired free amino acid as a product. Therefore, either a desuccinylase or chemical desuccinylation can be used as reported by Hibi and co-workers.23,27 The enzyme LasA can be used in a subsequent module to perform the final reaction step.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wilco Peeters, Monika Müller, and Natascha Smeets (InnoSyn B.V.) for advice and support in fermentative enzyme production as well as Math Boesten (DSM Resolve) for expert analytical support. This work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 MSCA ITN-EID program (BIOCASCADES under Grant Agreement No. 634200).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- αKG

α-ketoglutarate

- CFE

cell-free extract

- KPI buffer

potassium phosphate buffer

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c01122.

Additional experimental details of GC and LCMS chromatograms for compounds used in model reaction in module 2 at times of 5, 30, and 60 min; MS spectra of substrate and product of model reaction in module 2; HMBC-NMR and HMQC-NMR spectra of product mixture of model reaction in module 2; and primer list for cloning of SadA in pET28a(+) vector (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hollmann F.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Buehler K.; Schallmey A.; Bühler B. Enzyme-mediated oxidations for the chemist. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 226–265. 10.1039/C0GC00595A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov S. V.; Kodera T.; Samsonova N. N.; Kotlyarova V. A.; Rushkevich N. Y.; Kivero A. D.; Sokolov P. M.; Hibi M.; Ogawa J.; Shimizu S. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli to produce (2S, 3R, 4S)-4-hydroxyisoleucine. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 88, 719–726. 10.1007/s00253-010-2772-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters C.; Buller R. Industrial Application of 2-Oxoglutarate-Dependent Oxygenases. Catalysts 2019, 9, 221. 10.3390/catal9030221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busby R. W.; Chang M. D.; Busby R. C.; Wimp J.; Townsend C. A. Expression and purification of two isozymes of clavaminate synthase and initial characterization of the iron binding site. General error analysis in polymerase chain reaction amplification. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 4262–4269. 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe P.; Kamps J. J. A. G.; Schofield C. J.; Lohans C. T. Roles of 2-oxoglutarate oxygenases and isopenicillin N synthase in β-lactam biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2018, 35, 735–756. 10.1039/C8NP00002F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillwig M. L.; Liu X. A new family of iron-dependent halogenases acts on freestanding substrates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 921–923. 10.1038/nchembio.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffan N.; Grundmann A.; Afiyatullov S.; Ruan H.; Li S.-M. FtmOx1, a non-heme Fe(II) and alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase, catalyses the endoperoxide formation of verruculogen in Aspergillus fumigatus. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 4082–4087. 10.1039/b908392h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins J. M.; Ryle M. J.; Clifton I. J.; Dunning Hotopp J. C.; Lloyd J. S.; Burzlaff N. I.; Baldwin J. E.; Hausinger R. P.; Roach P. L. X-ray crystal structure of Escherichia coli taurine/alpha-ketoglutarate dioxygenase complexed to ferrous iron and substrates. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 5185–5192. 10.1021/bi016014e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmetag V.; Samel S. A.; Thomas M. G.; Marahiel M. A.; Essen L.-O. Structural basis for the erythro-stereospecificity of the L-arginine oxygenase VioC in viomycin biosynthesis. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 3669–3682. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju J.; Ozanick S. G.; Shen B.; Thomas M. G. Conversion of (2S)-arginine to (2S,3R)-capreomycidine by VioC and VioD from the viomycin biosynthetic pathway of Streptomyces sp. strain ATCC11861. ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 1281–1285. 10.1002/cbic.200400136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibi M.; Kawashima T.; Kodera T.; Smirnov S. V.; Sokolov P. M.; Sugiyama M.; Shimizu S.; Yokozeki K.; Ogawa J. Characterization of Bacillus thuringiensi s L-isoleucine dioxygenase for production of useful amino acids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 6926–6930. 10.1128/AEM.05035-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessner W.-D. Systems Biocatalysis: Development and engineering of cell-free “artificial metabolisms” for preparative multi-enzymatic synthesis. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 658–664. 10.1016/j.nbt.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu P.; Dong X.; Wang Y.; Liu L. Enzymatic production of α-ketoglutaric acid from L-glutamic acid via L-glutamate oxidase. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 179, 56–62. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X.; Chen R.; Chen L.; Liu L. Enhancement of alpha-ketoglutaric acid production from l-glutamic acid by high-cell-density cultivation. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2016, 126, 10–17. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2016.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaduskar R. D.; Pinto A.; Scaglioni L.; Musso L.; Dallavalle S. Synthesis of the Tripeptide Antibiotic Resormycin. Synthesis 2017, 49, 5351–5356. 10.1055/s-0036-1588553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeGoey D. A.; Kati W. M.; Hutchins C. W.; Donner P. L.; Krueger A. C.; Randolph J. T.; Motter C. E.; Nelson L. T.; Patel S. V.; Matulenko M. A.; Keddy R. G.; Jinkerson T. K.; Soltwedel T. N.; Liu D.; Pratt J. K.; Rockway T. W.; Maring C. J.; Hutchinson D. K.; Flentge C. A.; Wagner R.; Tufano M. D.; Betebenner D. A.; Lavin M. J.; Sarris K.; Woller K. R.; Wagaw S. H.; Califano J. C.; Li W.; Caspi D. D.; Bellizzi M. E. Proline derivatives as anti-viral agents and their preparation and use in the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. U.S. Pat. Appl. Publ. 2019, 338. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan S.; Lu Z.; Beeson T.; Chapman K. T.; Schleif W. A.; Olsen D. B.; Stahlhut M.; Rutkowski C. A.; Gabryelski L.; Emini E.; Tata J. R. Synthesis of novel HIV protease inhibitors (PI) with activity against PI-resistant virus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 5432–5436. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson R. L.; Singh J.; Kissick T. P.; Patel R. N.; Szarka L. J.; Mueller R. H. Synthesis of l-β-hydroxyvaline from α-keto-β-hydroxyisovalerate using leucine dehydrogenase from Bacillus species. Bioorg. Chem. 1990, 18, 116–130. 10.1016/0045-2068(90)90033-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abderhalden E.; Heyns K. Die Synthese von α-Amino-β-oxy- n -buttersäure, α-Amino-β-oxy-isovaleriansäure (β-Oxy-valin) und α-Amino-β-oxy- n -valeriansäure (β-Oxy-norvalin), zugleich ein Beitrag zur Frage des Vorkommens dieser Oxy-aminosäuren als Bausteine von Eiweißstoffen. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. B 1934, 67, 530–547. 10.1002/cber.19340670407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belokon Y. N.; Bulychev A. G.; Vitt S. V.; Struchkov Y. T.; Batsanov A. S.; Timofeeva T. V.; Tsyryapkin V. A.; Ryzhov M. G.; Lysova L. A. General method of diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of β-hydroxy-α-amino acids by condensation of aldehydes and ketones with glycine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 4252–4259. 10.1021/ja00300a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H.-M.; Miyakawa T.; Jia M. Z.; Nakamura A.; Ohtsuka J.; Xue Y.-L.; Kawashima T.; Kasahara T.; Hibi M.; Ogawa J.; Tanokura M. Crystal structure of a novel N-substituted L-amino acid dioxygenase from Burkholderia ambifaria AMMD. PLoS One 2013, 8, e63996. 10.1371/journal.pone.0063996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson D. G.; Young L.; Chuang R.-Y.; Venter J. C.; Hutchison III C. A.; Smith H. O. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 343–345. 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibi M.; Kasahara T.; Kawashima T.; Yajima H.; Kozono S.; Smirnov S. V.; Kodera T.; Sugiyama M.; Shimizu S.; Yokozeki K.; Ogawa J. Multi-enzymatic synthesis of optically pure β-hydroxy α-amino acids. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 767–774. 10.1002/adsc.201400672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ödman P.; Wellborn W. B.; Bommarius A. S. An enzymatic process to α-ketoglutarate from L-glutamate: the coupled system L-glutamate dehydrogenase/NADH oxidase. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2004, 15, 2933–2937. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.07.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rice G.; Yerabolu J.; Krishnamurthy R.; Springsteen G. The abiotic oxidation of organic acids to malonate. Synlett 2016, 28, 98–102. 10.1055/s-0036-1588649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A. S.; Finch G. L.; Michels P. C.; Wong J. W. Use of enzymes in the manufacture of active pharmaceutical ingredients—A science and safety-based approach to ensure patient safety and drug quality. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2012, 16, 1986–1993. 10.1021/op300153b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hibi M.; Kawashima T.; Kasahara T.; Sokolov P. M.; Smirnov S. V.; Kodera T.; Sugiyama M.; Shimizu S.; Yokozeki K.; Ogawa J. A novel Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase from Burkholderia ambifaria has β-hydroxylating activity of N-succinyl L-leucine. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 55, 414–419. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2012.03308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.