Abstract

We have carried out coarse-grained molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to study the self-assembly procedure of a system of randomly placed lipid molecules, water beads, and a nanoparticle (NP). The self-assembly results in the formation of the nanoparticle-supported lipid bilayer (NPSLBL), with the self-assembly mechanism being driven by events such as the formation of small lipid clusters, merging of the lipid clusters in the vicinity of the NP to form NP-embedded vesicle with a pore, and collapsing of that pore to eventually form the equilibrated NPSLBL system overcoming a large free energy barrier. Subsequently, we quantify the properties and the configurations of this NPSLBL system. We reveal that unlike our proposition of equal number of lipid molecules occupying the inner and outer leaflets in a recent report studying the properties of preassembled lipid bilayer, the equilibrated self-assembled NPSLBL system demonstrates a much larger number of lipid molecules occupying the outer leaflet as compared to the inner leaflet. Secondly, the thickness of the water layer entrapped between the NP and the inner leaflet shows similar values as that predicted by experiments and our previous study. Finally, we reveal that, similar to our previous study, the diffusivity of the lipid molecules in the outer leaflet is larger than that in the inner leaflet but, due to higher temperature employed during our simulations, are even larger than that predicted by our previous study.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The self-assembly of lipid molecules to form planar bilayers, or vesicles, or other heterogeneous structures (with entities such as proteins, DNA, carbon nanotubes, etc.) has been extensively probed using Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations.1–25 These studies have revealed critical information on issues such as (1) the conditions that decide if the self-assembly process will lead to the formation of a planar bilayer, or a closed vesicle, or a bicelle;3,9 (2) the structural and the packing orders in the lipid molecules during the process of self-assembly;3,5,12 (3) the effect of temperature on the phase change and the structural order;3 (4) the equilibrium protein position and configuration within a bilayer;14 (5) the effect of polyethylene glycol (PEG) on the self-assembled structure;17 (6) the structure of the carbon-nanotube-impregnated self-assembled bilayers;18,20 (7) the formation and the structure of DNA-lipid complexes;19 (8) the micelle formation by the lipid molecules around characteristic membrane proteins;15 (9) the properties and structures of mixed bilayers;21,25 (10) the lateral tension, elasticity, and mobility of the self-assembled membranes;1,3 (11) the trans-membrane electrostatic potential for charged lipids;10 (12) the conditions that lead to the rupture of the bilayer and enable the formation of worm-like micelle;24 (13) the formation of lipid corona on a nanoparticle;26 etc.

In the present paper, we employ MD simulations to study the self-assembly in a system of a nanoparticle and randomly placed POPC (palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) lipid molecules. The system eventually evolves to form a self-assembled nanoparticle-supported lipid bilayer (NPSLBL). The NPSLBL is a nanomaterial that has received tremendous recent interests for a large number of applications ranging from target-specific drug and gene delivery27–31 to characterizing molecules that respond to the variations in curvatures.32–34 Over the years, extensive experiments have been carried out to study the formation, properties, and applications of the NPSLBLs by using different kinds of lipids and different kinds of NPs. Pioneering works used the combination of SiO2 NPs and zwitterionic phospholipids.35 Wittenberg et al. used sub-micron (~700 nm) SiO2 NPs to fabricate such NPSLBLs using a mixture of different lipids (including egg phosphatidylcholine, ganglioside GM1, and other): these NPSLBLs were employed to form arrays, which in turn were used to obtain the equilibrium constant for cholera toxin binding to ganglioside GM1.36 Magnetic iron oxide NP based NPSLBLs has received increasing attentions as they can be used for bimolecular recognition with a magnetic separation.37,38 In addition, the lipids contact with the iron oxide NP directly in such iron oxide NP based NPSLBLs, unlike in silica NP based NPSLBLs, where there is a thin layer of water between the lipid bilayer and the NP.38 Recent developments include (a) fabricating NPSLBLs by combing negatively charged silica with anionic lipids by modifying the silica surface by using Avidin39 and (b) fabricating NPSLBLs by utilizing the interactions between the TiO2 NPs and zwitterionic inverse phosphocholine (CP) instead of normal phosphocholine (PC), and for this case, the TiO2 NPs and the lipid phosphate are chemically bonded, and hence the resultant NPSLBLs are more stable than the silica NP based NPSLBLs, where silica NP and the lipids are bonded by van der Waals force.40 In another study, Chung et al. demonstrated the formation of NPSLBLs via the interactions of highly charged (zeta potential of +60 mV) amine-functionalized 60-nm NPs with the negatively charged 50% DOPA/50% DOPC vesicles in presence of osmotic shock.41 Liu and co-workers, in a very interesting study, classified NPs into three distinct categories depending on whether it forms NPSLBLs or simply leads to a configuration where a NP is externally adsorbed on the surface of the vesicle.42 For example, they identified as type 1 oxide NP as NPs of Fe3O4, TiO2, ZrO2, Y2O3, In2O3, and Mn2O3 that formed NPSLBLs by interacting with DOCP (inverse phosphocholine version of DOPC) vesicles but led to NP-adsorbed-vesicle configuration with DOPC vesicles. They also identified as type 2 oxide NP as NPs of SiO2 that formed NPSLBLs with DOPC vesicle but led to NP-adsorbed-vesicle configuration with DOCP vesicles. Finally, they identified as type 3 oxide NPs as cationic ZnO and NiO NPs that damaged the vesicles by creating pores. In another study, Liu and co-workers showed that gold NPs undergo such surface adsorption (on the outer surface) of DOPC liposomes and the thickness of the interface between the NP and the DOPC liposome depends on the nature of the halide ions (Cl−, Br−, and I−) with which the gold NPs are capped.43 In this same study,43 the authors pointed out the manner in which the adsorption of the NPs on the vesicle surface led to a local phase transition of the vesicle. In another study, Liu and co-workers considered SiO2 NP (it was negatively charged for all ranges of studied pH) and TiO2 NP [it was positively (negatively) charged for small (large) pH] interacting with neutral liposomes (DOPC and DOCPe) and negatively charged liposomes (DOPS and DOCP).44 SiO2 NPs formed NPSLBL with the neutral liposomes, while the TiO2 NPs formed the NPSLBLs with the negatively charged liposomes at all pH (indicating that at larger pH, where the TiO2 NPs are negatively charged, forces other than the electrostatic interactions dictate the formation of the NPSLBL) and with neutral liposomes at a very small pH. In this study,44 the authors associated the formation of the NPSLBLs with the adsorption and the subsequent fusion of the NPs with the liposomes, which in turn implied the “leaking” of the liposomes releasing its original cargo (calcein for this study). Such leakage of liposomes thereby releasing their cargo due to the formation of NPSLBLs was also studied in another paper by the same group.45 Liu and co-workers also demonstrated the effect of particle hydrophobicity on the structure of the lipid layers: they showed that a hydrophilic NP (e.g., SiO2) forms a NPSLBL with the hydrophilic head of the lipid molecules of the inner layer (leaflet) facing the NP, while a hydrophobic NP (PLGA NP) forms only a supported monolayer (i.e., we get nanoparticle-supported lipid monolayer) with the hydrophobic tail of the lipid molecule facing the NP.46 Finally, Liu has provided a detailed picture of the problem of NPs interacting with liposomes and vesicles, thereby forming NPSLBLs as well as other non-suppoorted bilayer configurations in a recent review article.47

In a recent study,48 we had employed MD simulations to probe the configuration and properties of a pre-assembled NPSLBL. Previous MD simulation studies had probed the conditions that lead to the clustering of multiple lipid-encapsulated NPs trapped inside lipid bilayers.49 In another study, Chong et al. employed DPD (Dissipative Particle Dynamics) simulations to show that the insertion of self-assembled-monolayer (or SAM) functionalized NPs to lipid vesicles can be promoted by defects in the SAM structure: of course, such insertion did not lead to the formation of the NPSLBLs.50 On the other hand, Stelter and Keyes used hybrid MD/MC approach to study the number of lipids in the inner and the outer leaflets of a NPSLBL as a function of nanoparticle size.51 However both our previous paper (Ref. 48) and this paper (Ref. 51) considered a preformed NPSLBL rather than considering the NPSLBL to be formed by a self-assembly process. Furthermore, Ref. 51 used a three-bead coarse-grained model for describing the lipids: such a representation might not be a rigorous enough description of the lipids [for example, in both the present and previous study (Ref. 48), we considered a 13-bead Martini coarse-grained model (discussed later) for describing the lipids]. Olenick et al. also considered the interactions between a NP and lipid molecules by employing experiments and MD simulations; however, their study did not consider a closed NPSLBL system (by such a “closed” system, we refer to a structure where a lipid bilayer completely encapsulates the NP) and considered a system that had fragments of lipid bilayers supported on a NP.26 In this light, the present study is the one of the early attempts to quantify the properties and distribution of the lipid molecules in the leaflets of a closed NPSLBL obtained from self-assembly.

In the present study, we significantly improve the inferences of our previous report48 by (a) quantifying the process of the self-assembly that leads to the formation of the NPSLBL, (b) quantifying the configuration and the properties of the self-assembled NPSLBL and not the preformed NPSLBL, and (c) quantifying the influence of the type of NP on the configuration and the properties of the self-assembled NPSLBL. The simulation results point to interesting mechanisms of the self-assembly procedure: first, the randomly placed lipid molecules form small clusters, followed by the merging of these clusters in the vicinity of the NP to form NP-embedded vesicle. Such cluster merging or the nanostructure-embedded (when the nanostructure is a nanotube and not a NP) vesicle formation has been reported in previous studies on lipid bilayer self-assembly.3,18 Once the equilibrated self-assembled NPSLBL structure has been achieved, the properties and the configurations of the NPSLBL are quantified by pinpointing (a) the number distribution of the lipid molecules in the inner and the outer leaflet, (b) the number distribution of the water molecules entrapped between the NP and the inner leaflet, and (c) the diffusivity of the lipid molecules occupying the inner and outer leaflets and the bulk diffusivity of the entrapped water molecules. For the self-assembled NPSLBL system, the number of lipid molecules occupying the outer leaflet is found to be significantly larger than the number of lipid molecules occupying the inner leaflet. This is in stark contrast to what has been proposed for the preformed NPSLBL system (where we previously assumed identical number of lipid molecules occupying the inner and outer leaflets).48 The number of the entrapped water molecules and the thickness of this entrapped water layer is close to what has been predicted experimentally and by our previous study on preassembled NPSLBL system.48 Thirdly, our simulations establish that the diffusivities of the lipid molecules occupying both the inner and the outer leaflets are larger than those obtained in our previous study on pre-assembled NPSLBL system,48 although in both the present and the previous study,48 we witness that the diffusivity of the lipid molecules occupying the outer leaflet is significantly greater than that occupying the inner leaflet. Fourthly, we quantify the bulk diffusivity of the entrapped water and find it to be slightly larger than that obtained in our previous study on preformed NPSLBL system.48 Finally, we establish the influence of the nature of the NP of the NPSLBL on dictating the overall properties of the NPSLBL. Overall, we propose that this study provides a more realistic computational estimate of the properties of the NPSLBL by studying the self-assembled NPSLBL equilibrated from an initially random system, instead of considering a preformed NPSLBL system.48

METHODS

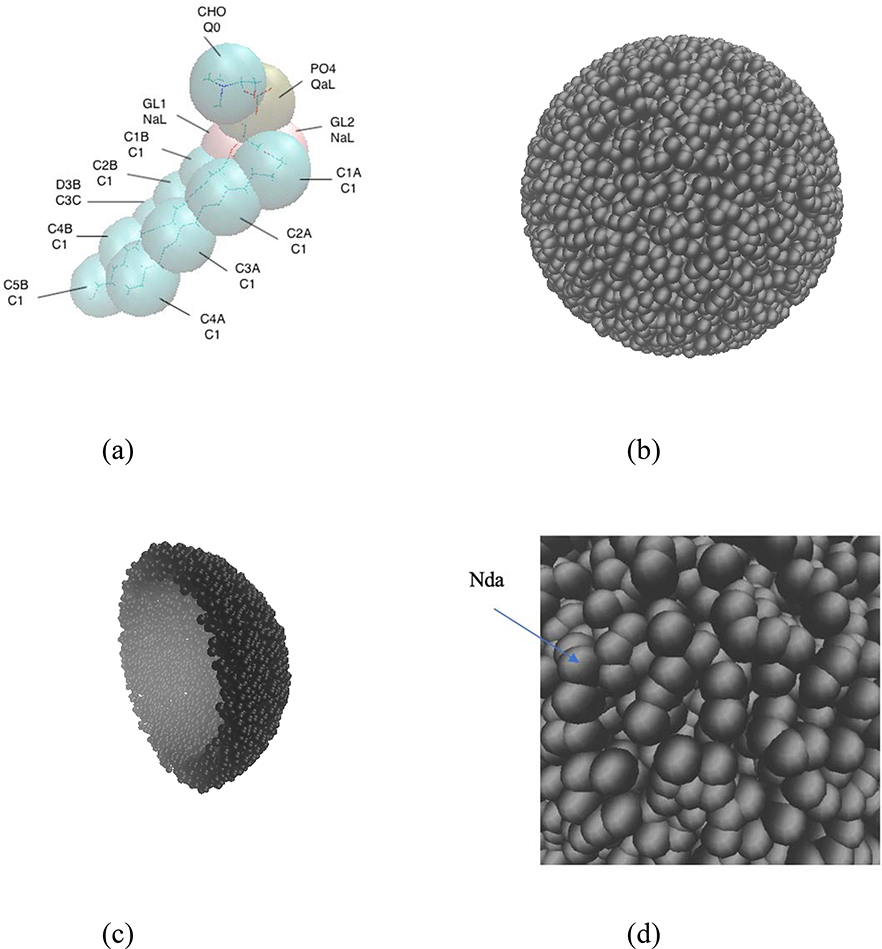

The simulations were conducted with the POPC lipid molecules, a NP, and water molecules. The POPC molecule, which was represented by the Martini model,52 is shown in Fig. 1(a). The NP consisted of Nda beads,52 which were randomly distributed in a spherical shell space of outer radius 7 nm and inner radius 5.5 nm, as shown in figure 1(b) and 1(c). The density of the Nda beads was 44 per nm3 so as to ensure that the water cannot penetrate the NP. We choose the Nda beads since this bead is hydrophilic and can serves as hydrogen donator and acceptor in the Martini model. In addition, this bead is not used in the POPC molecule. This system consisting of the POPC lipids and a NP composed of Nda beads is referred to as system A.

Figure 1:

(a) Martini model of the POPC lipid molecule, where the lipid molecule is represented by 13 large spheres (beads). Each of the beads is so labelled that their names are identified on the upper row and their types are identified on the bottom row (for example, the name of the “golden” color bead is “PO4” and its type is “QaL”). (b) Snapshot of the NP. (c) Snapshot of half of the NP. (d) Zoomed view of the NP surface.

The simulations are started from the initial structure shown in Figure 2(a). The initial configuration consists of the randomly distributed 3268 POPC molecules and water molecules around a NP (comprising of the Nda beads) in a cubic box of 22nm×22nm×22nm. This initial structure was obtained by using packmol.53 The water box consisted of 129163 Martini water beads and 14351 anti-freeze water beads.52 The purpose of adding such anti-freeze water beads has been discussed in our previous paper.48 Simulations were conducted by using the NAMD software package54 with the Martini force field.52 Periodic boundary conditions were employed by applying the NPT thermostat. The pressure was set to 1 bar and simulations were conducted with a 40fs time step. A total of four trajectories were run. The data were acquired every 50000 steps. 50 frames per trajectory were averaged over to obtain the results.

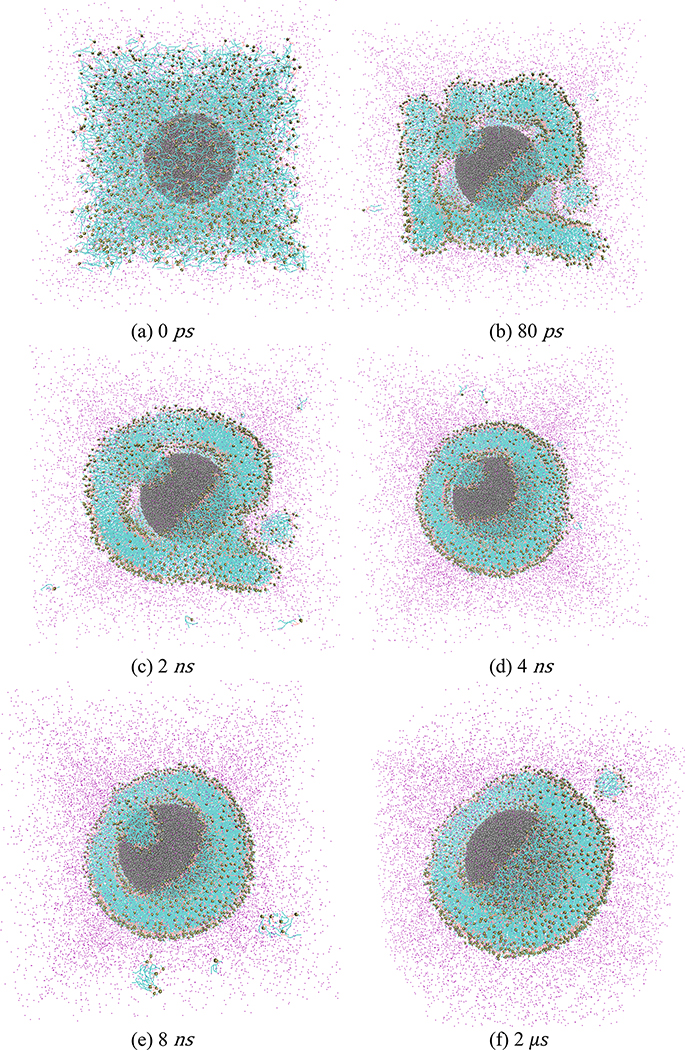

Figure 2:

Snapshot of the simulation of system A; (a): initial configuration; (b-h) snapshots quantifying the progress of the simulation. Also, the snapshots from (a-e) represent the simulations conducted at 310 K, while those from (f-h) represent the simulations conducted at 340 K. In (b) to (h), only 1/10th water are displayed for a clearer view. Below each snapshot, we provide the corresponding simulation step at which the snapshot has been taken. In the different subfigures, the following color codes have been used: Black: NP; light Green: hydrophobic tails of POPC molecules; bronze: hydrophilic heads of POPC molecules; purple: water.

We also consider another combination of lipid molecule and NP system: the lipid molecules are still POPC, while the NP is composed of P5 beads, which are more hydrophilic than the Nda beads.52 This system consisting of the POPC lipids and a NP composed of P5 beads is referred to as system B. The same simulation setting and processes employed for system A were employed for system B as well.

The interactions between Nda and water as well as P5 with water are both modelled using the Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential (ULJ) and the corresponding parameters are shown in table 1.52

| (1) |

where r is the distance between the two atoms.

Table 1:

Parameters for the Water-P5 and Water-Nda Lennard-Jones (LJ) interactions.

| Water-P5 | Water-Nda | |

|---|---|---|

| ε | −1.33843000 | −0.95602300 |

| σ | 5.27557163 | 5.27557163 |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Self-Assembly Mechanism

Figs. 2(a)–2(g) and Figs. S1(a)–S1(g) in the Supporting Information (SI) show the MD simulation snapshots depicting the time evolution of the systems A and B, respectively. Both set of simulations confirm the self-assembly-driven formation of the NPSLBL. In all the subfigures, only 1/10th of the total number of water molecules has been displayed to ensure a clearer view. In both the systems A and B, initially, the lipid molecules aggregate to form multiple small clusters [see Figs. 2(b, c) and Fig. S1(b, c)]. Subsequently, these clusters localize and merge near the surface of the NP and form a vesicle encapsulating the NP [see Fig. 2(d) and Fig. S1(d)]. Previous MD simulation studies on the self-assembly-driven formation of the planar lipid bilayers had reported the formation of such small clusters, which over time merge to form bigger cluster, eventually leading to the formation of the bilayers.3 Here the critical difference is that this merging of the clusters occur in the vicinity of the NP. However, such nanostructure-supported vesicle formation (here the nanostructure is this NP) has been reported in previous simulation studies where the lipid molecule self-assemble around nanotubes to form lipid-nanotube vesicle.18 Such aggregation of the lipid molecules around the nanostructure is possibly due to the corresponding lowering of the exposure of the lipid hydrophobic tails to the surrounding water. Obviously, the presence of the NP promotes such aggregation of the lipid molecules around NP. On the other hand, if the NP was absent the lipid molecules would have formed bilayer micelles (or nanovesicles or liposomes), which would have also prevented the unfavorable contact between the lipid hydrophobic tail and water. The possible reason why such bilayer micelles are prevented from formation in the presence of NPs is that such micelles are less stable due to the fluctuations of the unsupported bilayer; on the other hand, the structural support offered by the NP to the lipid molecules (assembling on the NP) makes the aggregates of lipid molecules (and eventually the lipid molecules constituting the NPSLBL, see below) more stable.

In the present study, NP-supported vesicle contains a large pore [see Fig. 2(e) and Fig. S1(e)]; furthermore, there are few small clusters that have not merged and are away from the vesicle [see Fig. 2(e) and Fig. S1(e)]. This entire structure (NP-supported vesicle with a large pore and some sparsely distributed clusters away from the vesicle) would take a long time to overcome the energy barrier for equilibration. To accelerate the simulation, therefore, we increased the temperature from 310K to 340K in one step [starting from the MD simulation step represented in Fig. 2(f) and Fig. S1(f), i.e., MD simulation step corresponding to the 2 μs]. As a result, the pore gradually closed [see Figs. 2(f, g) and Figs. S1(f, g)] and the sparsely distributed clusters (located away from the vesicle) merged with the vesicle. Eventually, we obtained a perfect pore-free NP-supported vesicle, which is equivalent to the NPSLBL (henceforth, referred to as the NPSLBL) [see Fig. 2(h) and Fig. S1(h)]. Finally, we equilibrated these NPSLBL systems by running the simulations further for another 2 μs.

Number Distribution of the Lipid Molecules in the Inner and Outer Leaflets

After obtaining the equilibrium configuration, we measured the radial distribution of the hydrophilic head of the POPC molecules, represented by the PO4 beads. The result is shown in Figure 3 with the horizonal axis providing the distance between the beads and the center of the NP. The clustering of the lipid molecules occur at two distinct ranges of the radial distances (namely 7nm ≤ r ≤ 8.5nm and 10.5nm ≤ r ≤ 12.5nm) confirming that there are two layers (or two leaflets) of lipids. We characterize the two leaflets by quantifying the number of lipid molecules present in each. We find that there are 1274 PO4 beads present at the location 7nm ≤ r ≤ 8.5nm and 1994 PO4 beads present at the location 10.5nm ≤ r ≤ 12.5nm for system A. In other words, there are 1274 POPC molecules located at the inner leaflet of the bilayer, and 1994 POPC molecules located at the outer leaflet of the bilayer for system A. If we define the radius of the inner (outer) leaflet as the average distance between the PO4 beads of inner (outer) leaflet and the NP center, then the inner radius is 7.86 nm and the outer radius is 11.79 nm. Therefore, the average LBL thickness is 3.93 nm. Also, from these quantifications we can infer that the surface coverage is 0.61 nm2 per lipid for the inner leaflet and 0.88 nm2 per lipid for the outer leaflet.

Figure 3:

Radial distribution of the POPC molecules, with the radial distance being represented by the distance between the PO4 head group and the center of NP, for (a) System A and (b) System B.

For system B, there are 1287 PO4 beads at the location 7nm ≤ r ≤ 8.5nm and 1981 PO4 beads present at the location 10.5nm ≤ r ≤ 12.5nm. As a result, there are 1287 POPC molecules located at the inner leaflet of the bilayer, and 1981 POPC beads located at the outer leaflet of the bilayer, with inner radius being 7.97 nm and the outer radius being 11.84 nm. Thus, the average LBL thickness is 3.87 nm. In addition, the surface coverage is 0.62 nm2 per lipid for the inner leaflet and 0.89 nm2 per lipid for the outer leaflet.

Please note that for both the systems A and B, two mutually countering effects dictate the number of lipids in the inner and the outer leaflets. The outer leaflet has a larger surface area that allows it to accommodate a larger number of lipid molecules. On the other hand, the presence of the supporting NP implies that the lipids in the inner leaflet are more compact, which in turn allows the inner leaflet to accommodate more lipid per unit area (or equivalenetly, a smaller surface area coverage per lipid). The effect of the larger area of the outer leaflet becomes more dominating, leading to a net larger number of lipids in the outer leaflet as compared to the inner leaflet.

It is worthwhile to compare the above findings with those of our previous study,48 where we considered a preformed NPSLBL. In that study,48 the preformed NPSLBL consisted of 1639 POPC molecules in the inner leaflet and 1639 POPC molecules in outer leaflet at 310 K and the NP was composed of Nda beads. In comparison, for the present study, these numbers are 1274 POPC molecules in the inner leaflet and 1994 POPC molecules in the outer leaflet at 340 K. Therefore, the self-assembly MD simulations reveal a critical facet of the LBL structure of the NPSLBL that was missing in our previous study:48 the number of lipid molecules in the inner and outer leaflet significantly vary from each other. The pre-assembled NPSLBL in our previous study showed very little change in the number of lipid molecules between inner and outer leaflet when the equilibration run was conducted with this pre-assembled state (with equal number of lipid molecules in the inner and outer leaflets). This stemmed from the fact that this pre-assembled state behaved as a meta-equilibrated configuration trapped at the local minimum due to the high energy barrier of lipid flip-flop. It is also interesting to note that this large difference in the number of lipid molecules between the inner and outer leaflet as revealed by the present study is much similar to the free nanovesicle (NV) simulated in our previous work, where there are 1302 and 1967 POPC molecules in inner and outer leaflets respectively.48 This configurational similarity between self-assembled NPSLBL and the free NV of the same size, in addition to the easy controllability of the size of the NPSLBL, potentially makes the NPSLBL a better choice for studying the membrane curvature sensing by curvature-sensitive moleucles.32

Number Distribution of the Water Molecules Entrapped between the Nanoparticle and the Inner Leaflet

In Figure 4, we show the radial distribution of the coarse-grained (CG) water beads and anti-freeze (AF) water beads. The y axis is the density of the CG water and AF water normalized over the standard density (ρS) of the corresponding water (ρS = 33/4×0.9 and ρS = 33/4×0.1 per nm2 for the CG water and the AF water, respectively). The result shows that there is a thin layer of water entrapped between the NP and the inner lipid leaflet in the self-assembled NPSLBL structure for both the systems A and B. This entrapped water layer is a relefction of the large hydrophilicity of the Nda beads (for system A) and the P5 beads (system B) that ensures that the NP prefers to be in contact with a thin layer of water rather than in direct contact with the lipid molecules. It is useful to note that system B shows a larger value of the density of the entrpped water as compared to system A. This stems from the fact that P5 beads (consituting the NP in system B) are more hydrophilic than the Nda beads (consituting the NP in system A). For both the systems A and B, the average thickness of the confined water is found to be around 1.5nm. This thickness of the water layer trapped between the NP and the lipid inner leaflet is comparable to the experimental value of 1 to 2 nm (Ref. 55) and confirm the rational of our previous simulation design where we had introduced a two-layer thick coarse-grained water beads between the NP and the inner leaflet in our pre-assembled NPSLBL system.48

Figure 4:

Radial distribution of the coarse-grained and anti-freeze water beads with the radial distance being represented by the distance between the PO4 head group and the center of NP, for (a) System A and (b) System B.

3D Diffusivity of the Lipid Molecules and Confined Water Molecules

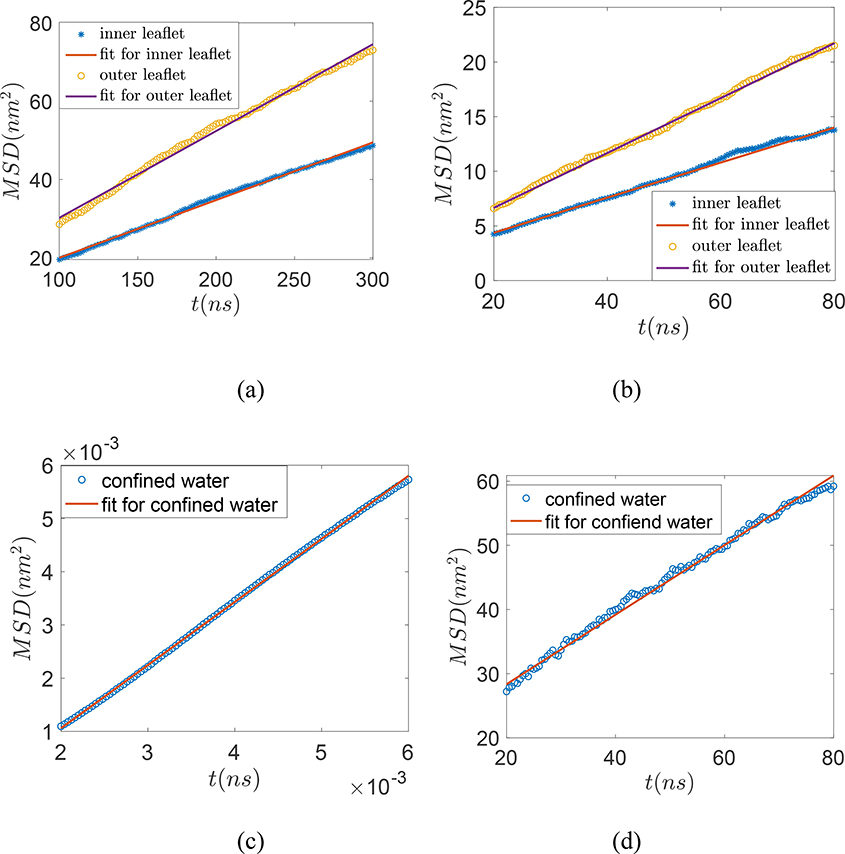

In Figures 6(a) and 6(b), we plot the <MSD>-vs-t variation and thereby quantify the 3D diffusivity (D3) of the lipid molecules occupying the inner and outer leaflets of the self-assembled NPSLBL by using Einstein relation, i.e.,

| (2) |

Here 〈MSD〉 is the mean square displacement and t is the time. D3 is calculated from the slope of the linear region of the 〈MSD〉-vs-t curve. For system A, D3 values for the lipid molecules occupying the inner and the outer leaflets are 2.45×10−7 cm2/s and 3.69×10−7 cm2/s, respectively. For system B, D3 values for the lipid molecules occupying the inner and the outer leaflets are 2.67×10−7 cm3/s and 4.19×10−7 cm3/s, respectively. These findings confirm that for both the systems A and B, the diffusivity of the lipid molecules in the outer leaflet is significantly higher than that of the lipid molecules in the inner leaflet. Ref. 12, studying DPPC nanovesicles (i.e., spherical LBLs without any encapsulating NP) using MD simulations, has provided very similar values (as obtained for systems A and B from our simulations) of the diffusivities of the lipid molecules in the inner and outer leaflets clearly demonstrating larger diffusivity values for the lipid molecules in the outer leaflet. Ref. 56 provides an average experimental diffusivity value for the POPC lipid molecules of the POPC LBL system that is partly supported on a NP and partly on a planar substrate. Their diffusivity values are nearly one order less than that obtained from our MD simulation studies. We ascribe such a difference to the nature and size of the NP (both of which are different as compared to the system A of our study) as well as the presence of an additional planar support in Ref. 56. In addition, Ref. 57 and 58 measured the lateral diffusivity of the individual monolayer of silica NPSLBLs directly and found that the diffusivity of lipids in outer leaflets is two times higher than inner leaflets.

Finally, in Fig. 6(c) and 6(d), we plot the <MSD>-vs-t variation for the confined water molecules entrapped between the NP and the inner leaflet and quantify the diffusivity (D3) using eq. (2). For system A, D3=1.98 ×10−6 cm3/s for the entrapped water molecules. This diffusivity value is very similar (D3=1.95 ×10−6 cm3/s) for the entrapped water molecules obtained from our previous MD simulation study with preformed NPSLBL.35 On the other hand, for system B, we obtain D3=0.94×10−6 cm2/s for the entrapped water molecules; this diffusivity value is less than half of that of the system A stemming from the larger hydrophilicity of P5 beads as compared to the Nda beads.

Effect of the NP surface Charge on the formation and Properties of the NPSLBL

There have been a significant number of studies probing the interactions between charged NPs and charged/neutral lipid vesicles.41–44 In contrast in this paper we have considered two types of uncharged NPs. For example, in previous reports, electrostatic interactions have been considered to be the primary driving forces dictating the adsorption of positively charged amine-functionalized 60-nm NPs (having a zeta potential of +60 mV) with the negatively charged 50% DOPA/50% DOPC vesicles.41 Interestingly, the mere existence of such electrostatic attraction does not lead to the formation of the NPSLBLs in this case; one also needs to employ an additional osmotic shock to ensure the rupturing of the vesicles to form the NPSLBLs.41 Positive surface charges on the NPs (for ZnO and NiO NPs) have also been identified to damage the liposomes of zwitterionic lipids (DOPC and DOCP) by adsorbing on the liposomes and creating pores.42 On the other hand, engineering negative surface charges on the surface of gold NPs by capping them with layers of halide ions (Cl−, Br−, and I−) enable the NPs to get adsorbed on the surface of the DOPC liposomes (without forming any NPSLBL): such adsorption leads to a localized phase change at the location of the lipid molecules where they are adsorbed and the size of the interface between the NP and the lipid molecules strongly depend on the nature of the halide ions.43 Also, studies have shown the manner in which electrostatic effects dictate the formation of the NPSLBLs due to the interactions of the positively charged TiO2 NPs (at smaller pH) and negatively charged DOPS liposomes.44 However, the same study (Ref. 44) reports the formation of the NPSLBLs due to the interaction of the negatively charged TiO2 NPs (at larger pH) and negatively charged liposomes, indicating the prevalence of the non-electrostatic forces in dictating the formation of the NPSLBLs.

All the above-described studies are experimental studies that do not quantify the detailed self-assembly process, which would shed light on the exact mechanism of formation (or failure to form) the NPSLBLs. The MD simulation framework proposed in this paper, which for the first time probes the formation of the NPSLBL through self-assembly routes, would be helpful to study the self-assembly driven formation of the NPSLBL with charged NPs. Of course, several modifications to the current framework would be needed to capture the problem involving charged NPs. For example, we would need to account the for the presence of the salt ions (most of the experiments on the formation of the NPSLBLs using charged NPs are conducted in salt solutions of concentration of ~100 mM) and the manner in which they dictate the length scale (effectively the Debye lengths quantifying the formation of the EDLs on the surfaces of the NP and the lipids) over which the NP and the lipid molecules would interact. Given that the inclusion of such salt ions would involve consideration of the long-range Columbic forces between large numbers of entities would lead to a significant increase in the computational cost of the problem. Therefore, probing such a problem is beyond the scope of the present study and would be considered in a future effort.

Effect of the NP Philicity/Phobicity and Defects (variation/distribution of philicity and surface charge on the NP surface) on the formation and Properties of the NPSLBL

The formation of the NPSLBL typically requires a hydrophilic NP. The reason is simple: the hydrophilic head of the outer layer of the lipid should be in contact with the bulk solution, while the hydrophilic head of the inner layer of the lipid should be in contact of an entity that prefers the interaction with the lipid hydrophilic head. This entity, therefore, has to be something that is hydrophilic: that is precisely the reason that one needs to have a hydrophilic NP for the formation of the NPSLBL. Interestingly the interaction of a hydrophobic NP (such as PLGA) with the lipid molecules gives rise to the formation of the lipid monolayer (where the hydrophilic head faces the bulk solution and the hydrophobic tail faces the NP) instead of the NPSLBL.46

For the case of the NP with defects, i.e., where there is a spatial distribution of hydrophilicity (wettability) on the NP surface, it is possible that one still witnesses the formation of the NPSLBL with a non-uniform thickness of the intervening water layer (between the NP and the inner leaflet) with a thicker layer at the location of the NP with larger hydrophilicity. Obviously, such a structure is only possible where there might be some variation of the wettability on the NP surface without any region becoming hydrophobic. Given that a hydrophobic surface fails to support a bilayer (and only supports a monolayer),46 for a NP with widely varying wettability (some region hydrophilic and some region hydrophobic), the formation of a continuous NP-encapsulating LBL might not be possible.

Such defects also entail the possibilities of the variation of the surface charges (or surface charge densities) on the NP surface. For a case where this NP surface charge varies in such a manner that it does not change the sign, it is still expected to form a NPSLBL by electrostatically interacting with liposomes of oppositely charged lipid molecules. Of course, the variation of the surface charge (or surface charge density) would mean that there would be some local variation in the properties of the bilayer. For example, one would anticipate a thinner water layer (intervening between the inner lipid layer and the NP) at the location of the NP with larger surface charge density, as that part of the NP would attract the lipid molecules more strongly. Of course, a delineation of such effects of the defects on the NP surface (distribution of wettability or surface charges) is also beyond the scope of the present study and would be considered to be a potential investigation in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Coarse-grained MD simulations have been employed to study for the first time the self-assembly-driven formation of NPSLBL. We discover critical mechanisms that drive the self-assembly process including the formation of small lipid clusters, merging of these clusters in the vicinity of the NP to form NP-embedded vesicle with a pore, and the disappearance of that pore overcoming a large energy barrier to eventually form the equilibrated NPSLBL. Our results also reveal critical information on the properties of the self-assembled NPSLBL, such as the area per lipids, the number of lipids, and the diffusivity of the lipids in the inner and outer leaflets as well as the thickness and diffusivity of the water molecular layer confined between the NP and the inner leaflet. These quantifications eventually enable us to revisit the predictions on the properties and configurations of the preformed NPSLBL system studied in our previous work48 and establish the present study as the most complete computational predictive study on the properties and configurations of the NPSLBL till date that can be used for any future simulation-based analyses of NPSLBL system.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5:

(a) <MSD>-vs-time for the POPC lipid molecules occupying inner and outer leaflets for the NPSLBL for (a) System A and (b) System B. <MSD>-vs-time for the confined water entrapped between the NP and the inner leaflet of the lipid bilayer for (c) System A and (d) System B. We employ eq.(1) to obtain the corresponding D3 values from the slope of each of the different <MSD>-vs-time plots.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the University-of-Maryland-National-Cancer-Institute Partnership for Integrative Cancer Research (H.J., K.S.R., and S.D.) and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research (K.S.R.).

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Molecular Dynamics simulation snapshots showing the self-assembly driven formation of the NPSLBL for system B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goetz R; Gompper G; Lipowsky R Mobility and Elasticity of Self-Assembled Membranes. Phys. Rev. Lett 1999, 82, 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brannigan G; Philips PF; Brown FLH Flexible Lipid Bilayers in Implicit Solvent. Phys. Rev. E 2005, 72, 011915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schindler T; Kröner D; Steinhauser MO On the Dynamics of Molecular Self-Assembly and the Structural Analysis of Bilayer Membranes using Coarse-grained Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1868, 1955–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skjevik A, A.; Madej BD; Dickson CJ; Teigen K; Walker RC; Gould IR All-atom Lipid Bilayer Self-assembly with the AMBER and CHARMM Lipid Force Fields. Chem. Comm 2015, 51, 4402–4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skjevik A, A.; Madej BD; Dickson CJ; Lin C; Teigen K; Walker RC; Gould IR Simulation of Lipid Bilayer Self-assembly using All-atom Lipid Force Fields. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2016, 18, 10573–10584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shelley JC; Shelley MY; Reeder RC; Bandyopadhyay S; Klein ML A Coarse Grain Model for Phospholipid Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 4464–4470. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelley JC; Shelley MY; Reeder RC; Bandyopadhyay S; Moore PB; Klein ML Simulations of Phospholipids Using a Coarse Grain Model. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 9785–9792. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z-J; Deserno M Simulations of Phospholipids Using a Coarse Grain Model. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 11207–11220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyubartsev AP Multiscale Modeling of Lipids and Lipid Bilayers. Eur. Biophys. J 2005, 35, 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orsi M; Michel J; Essex JW Coarse-grain Modelling of DMPC and DOPC Lipid Bilayers. J. Phys. Cond. Matt 2010, 22, 155106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y; Sigurdsson JK; Brandt E Dynamic Implicit-solvent Coarse-grained Models of Lipid Bilayer Membranes: Fluctuating Hydrodynamics Thermostat. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 88, 023301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrink SJ; Mark AE Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the Formation, Structure, and Dynamics of Small Phospholipid Vesicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 15233–15242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Vries AH; Mark AE; Marrink SJ Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the Spontaneous Formation of a Small DPPC Vesicle in Water in Atomistic Detail. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 4488–4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott KA; Bond PJ; Ivetac A; Chetwynd AP; Khalid S; Sansom MSP Coarse-Grained MD Simulations of Membrane Protein-Bilayer Self-Assembly. Structure 2008, 16, 621–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bond PJ; Cuthbertson JM; Deol SS; Sansom MSP MD Simulations of Spontaneous Membrane Protein/Detergent Micelle Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 15948–15949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bond PJ; Sansom MSP Insertion and Assembly of Membrane Proteins via Simulation. Insertion and Assembly of Membrane Proteins via Simulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 2697–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H; Pastor RW Coarse-Grained Model for PEGylated Lipids: Effect of PEGylation on the Size and Shape of Self-Assembled Structures. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 7830–7837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dutt M; Kuksenok O; Nayhouse MJ; Little SR; Balazs AC Modeling the Self-Assembly of Lipids and Nanotubes in Solution: Forming Vesicles and Bicelles with Transmembrane Nanotube Channels. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 4769–4782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalid S; Bond PJ; Holyoake J; Hawtin RW; Sansom MSP DNA and Lipid Bilayers: Self-assembly and Insertion. J. R. Soc. Interface 2008, 5, S241–S250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace EJ; Sansom MSP Carbon Nanotube Self-assembly with Lipids and Detergent: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 045101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orsi M; Essex JW Physical Properties of Mixed Bilayers Containing Lamellar and Nonlamellar Lipids: Insights from Coarse-grain Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Faraday Discuss. 2013, 161, 249–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marrink SJ; de Vries AH; Mark AE Coarse Grained Model for Semiquantitative Lipid Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 750–760. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shih AH; Arkhipov A; Freddolino PL; Schulten K Coarse Grained Protein-Lipid Model with Application to Lipoprotein Particles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 3674–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noguchi H Solvent-free Coarse-grained Lipid Model for Large-scale Simulations. J. Chem. Phys 2011, 134, 055101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koldsø H; Shorthouse D; Helie J; Sansom MSP Lipid Clustering Correlates with Membrane Curvature as Revealed by Molecular Simulations of Complex Lipid Bilayers. PLOS Comput. Biol 2014, 10, e1003911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olenick LL; Troiano JM; Vartanian A; Melby ES; Mensch AC; Zhang L; Hong J; Mesele O; Qiu T; Bozich J; et al. Lipid Corona Formation from Nanoparticle Interactions with Bilayers. Chem 2018, 4, 2709–2723. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashley CE; Carnes EC; Phillips GK; Padilla D; Durfee PN; Brown PA; Hanna TN; Liu J; Phillips B; Carter MB; Carroll NJ; Jiang X; Dunphy DR; Willman CL; Petsev DN; Evans DG; Parikh AN; Chackerian B; Wharton W; Peabody DS; Brinker CJ The Targeted Delivery of Multicomponent Cargos to Cancer Cells by Nanoporous Particle-Supported Lipid Bilayers. Nature Mater. 2011, 10, 389–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarn D; Ashley CE; Xue M; Carnes EC; Zink JI; Brinker CJ Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle Nanocarriers: Biofunctionality and Biocompatibility. Acc. Chem. Res 2013, 46, 792–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J; Jiang X; Ashley C; Brinker CJ Electrostatically Mediated Liposome Fusion and Lipid Exchange with a Nanoparticle-Supported Bilayer for Control of Surface Charge, Drug Containment, and Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 7567–7569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin Y-S; Haynes CL Impacts of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle Size, Pore Ordering, and Pore Integrity on Hemolytic Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 4834–4842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J; Stace-Naughton A; Jiang X; Brinker CJ Porous Nanoparticle Supported Lipid Bilayers (Protocells) as Delivery Vehicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 1354–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu R; Gill RL; Kim EY; Briley NE; Tyndall ER; Xu J; Li C; Ramamurthi KS; Flanagan JM; Tian F Spherical Nanoparticle Supported Lipid Bilayers for the Structural Study of Membrane Geometry-Sensitive Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 14031–14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gill RL Jr.; Castaing J-P; Hsin J; Tan IS; Wang X; Huang KC; Tian F; Ramamurthi KS Structural Basis for the Geometry-driven Localization of a Small Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E1908–E1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim EW; Tyndall ER; Huang KC; Tian F Dash-and-Recruit Mechanism Drives Membrane Curvature Recognition by the Small Bacterial Protein SpoVM. Cell Syst. 2017, 5, 518–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bayer TM; Bloom M. Physical Properties of Single Phospholipid Bilayers Adsorbed to Micro Glass Beads. A New Vesicular Model System Studied by 2h-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Biophys. J 1990, 58 (2), 357–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wittenberg NJ; Johnson TW; Oh S-H. High-Density Arrays of Submicron Spherical Supported Lipid Bilayers. Anal. Chem 2012, 84, 8207–8213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Cuyper M; De Meulenaer B; Van der Meeren P; Vanderdeelen J Catalytic Durability of Magnetoproteoliposomes Captured by High-Gradient Magnetic Forces in a Miniature Fixed-Bed Reactor. Biotech. Bioeng 1996, 49, 654–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Troutier A-L; Catherine L. An Overview of Lipid Membrane Supported by Colloidal Particles. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci 2007, 133, 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gopalakrishnan G; Rouiller I; Colman DR; Lennox RB. Supported Bilayers Formed from Different Phospholipids on Spherical Silica Substrates. Langmuir 2009, 25, 5455–5458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang F; Liu J. A Stable Lipid/TiO2 Interface with Headgroup-Inversed Phosphocholine and a Comparison with SiO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 11736–11742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung PJ; Hwang HL; Dasbiswas K; Leong A; Lee KYC Osmotic Shock-Triggered Assembly of Highly Charged, Nanoparticle-Supported Membranes. Langmuir 2018, 34, 13000–13005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y; Wang F; Liu J Headgroup-Inversed Liposomes: Biointerfaces, Supported Bilayers and Applications. Langmuir 2018, 34, 9337–9348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X; Li X; Xu W; Zhang X; Huang Z; Wang F; Liu J Sub-Angstrom Gold Nanoparticle/Liposome Interfaces Controlled by Halides. Langmuir 2018, 34, 6628–6635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X; Li X; Wang H; Zhang X; Zhang L; Wang F; Liu J Charge and Coordination Directed Liposome Fusion onto SiO2 and TiO2 Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2019, 35, 1672–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y; Liu J Leakage and Rupture of Lipid Membranes by Charged Polymers and Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2020, 36, 810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopez A; Liu J DNA Oligonucleotide-Functionalized Liposomes: Bioconjugate Chemistry, Biointerfaces, and Applications. Langmuir 2018, 34, 15000–15013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J Interfacing Zwitterionic Liposomes with Inorganic Nanomaterials: Surface Forces, Membrane Integrity, and Applications. Langmuir 2016, 32, 4393–4404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jing H; Wang Y; Desai PR; Ramamurthi KS; Das S Nanovesicles Versus Nanoparticle- Supported Lipid Bilayers: Massive differencesin Bilayer Structures and in Diffusivities of Lipid Molecules and Nanoconfined Water. Langmuir 2019, 35, 2702–2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chan H; Kral P Nanoparticles Self-Assembly within Lipid Bilayers. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 10631–10637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chong G; Foreman-Ortiz IU; Wu M; Bautista A; Murphy CJ; Pedersen JA; Hernandez R Defects in Self-Assembled Monolayers on Nanoparticles Prompt Phospholipid Extraction and Bilayer-Curvature-Dependent Deformations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 27951–27958. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stelter D; Keyes T. Lipid Packing in Lipid-Wrapped Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 6755–6762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marrink SJ; Risselada HJ; Yefimov S; Tieleman DP; de Vries AH The MARTINI Force Field: Coarse Grained Model for Biomolecular Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 7812–7824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martínez L; Andrade R; Birgin EG; Martínez JM PACKMOL: A Package for Building Initial Configurations for Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Comput. Chem 2009, 30, 2157–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phillips JC; Braun R; Wang W; Gumbart J; Tajkhorshid E; Villa E; Chipot C; Skeel RD; Kale L; Schulten K Scalable Molecular Dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem 2005, 26, 1781–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Charitat T; Bellet-Amalric E; Fragneto G; Graner F Adsorbed and Free Lipid Bilayers at the Solid-Liquid Interface. Eur. Phys. J. B 1999, 8, 583–593. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woodward X; Stimpson EE; Kelly CV Single-Lipid Tracking on Nanoscale Membrane Buds: The Effects of Curvature on Lipid Diffusion and Sorting. BBA - Biomembranes 2018, 1860, 2064–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hetzer M; Heinz S; Grage S; Bayerl TM Asymmetric Molecular Friction in Supported Phospholipid Bilayers Revealed by NMR Measurements of Lipid Diffusion. Langmuir 1998, 14, 982–984. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmitt J; Danner B; Bayer TM Polymer Cushions in Supported Phospholipid Bilayers Reduce Significantly the Frictional Drag between Bilayer and Solid Surface. Langmuir 2001, 17 (1), 244–246. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.